On 24 January, the leaders Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger met in Niamey under the auspices of the Liptako-Gourma Authority (LGA). The goal of this sub-regional organization is to allow these three countries to coordinate the development of the Liptako-Gourma region (Sahel Standard, 24 January 2017), which includes, in whole or in part, nineteen provinces of Burkina Faso, four administrative regions of Mali, and two departments and an urban community in Niger. This 370,000-km² area is characterised by particularly porous borders and the region has become of increasing concern to the governments making up the LGA in the context of rising insecurity across the Sahel.

In an attempt to meet this growing threat, the leaders of the three countries announced at the Niamey meeting that they would be setting up a Joint Task Force (JTF) to combat “terrorism” in the Liptako-Gourma region (Africa News, 25 January 2017). According to the President of Niger, this force will be set up along similar lines to the multinational force created to combat Boko Haram in the Lake Chad Basin. As with the Lake Chad basin, the attacks in the Liptako-Gourma region often involve border crossings by militants before and/or after the attacks are carried out. The groups involved include the so-called Islamic State, AQIM and their various affiliates, among others. Some of the most recent attacks include an assault by an Islamic State-affiliate on a military post in Niger on 22 February which killed 16 soldiers (Xinhua, 26 February 2017) and coordinated attacks on police stations in Baraboule and Tongomayel in Burkina Faso on 27 February by Ansaroul Islam, an AQIM-affiliate (Xinhua, 28 February 2017).

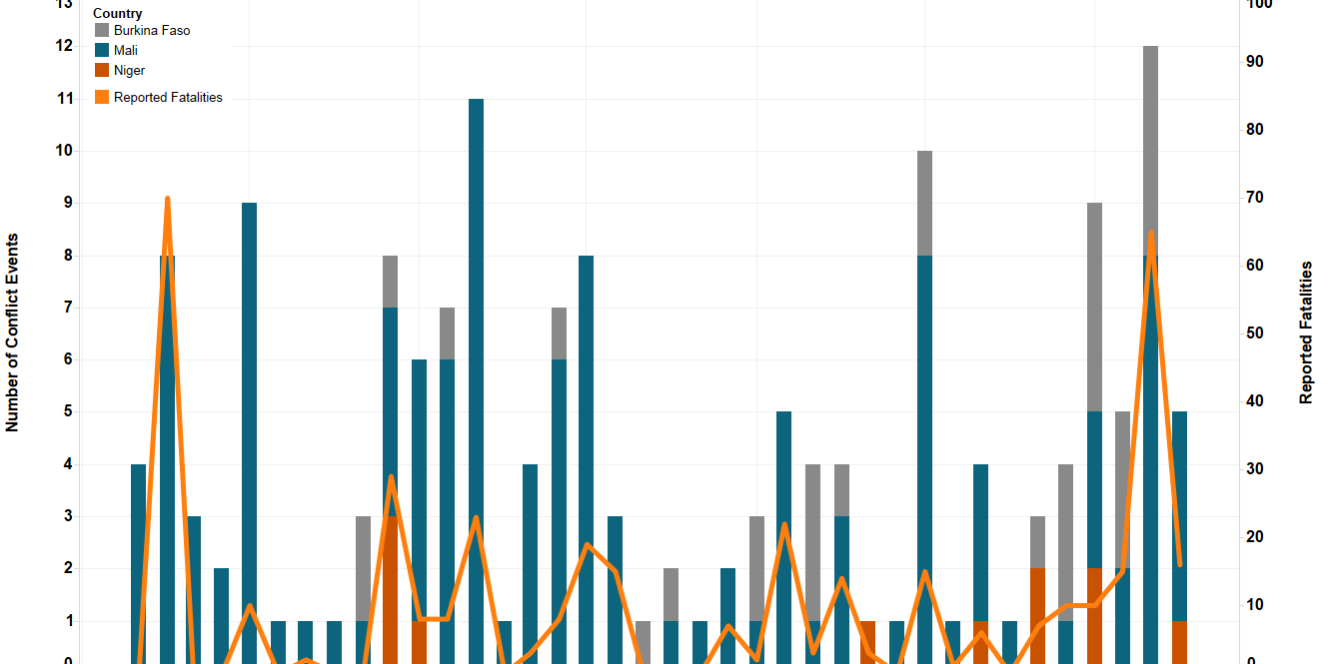

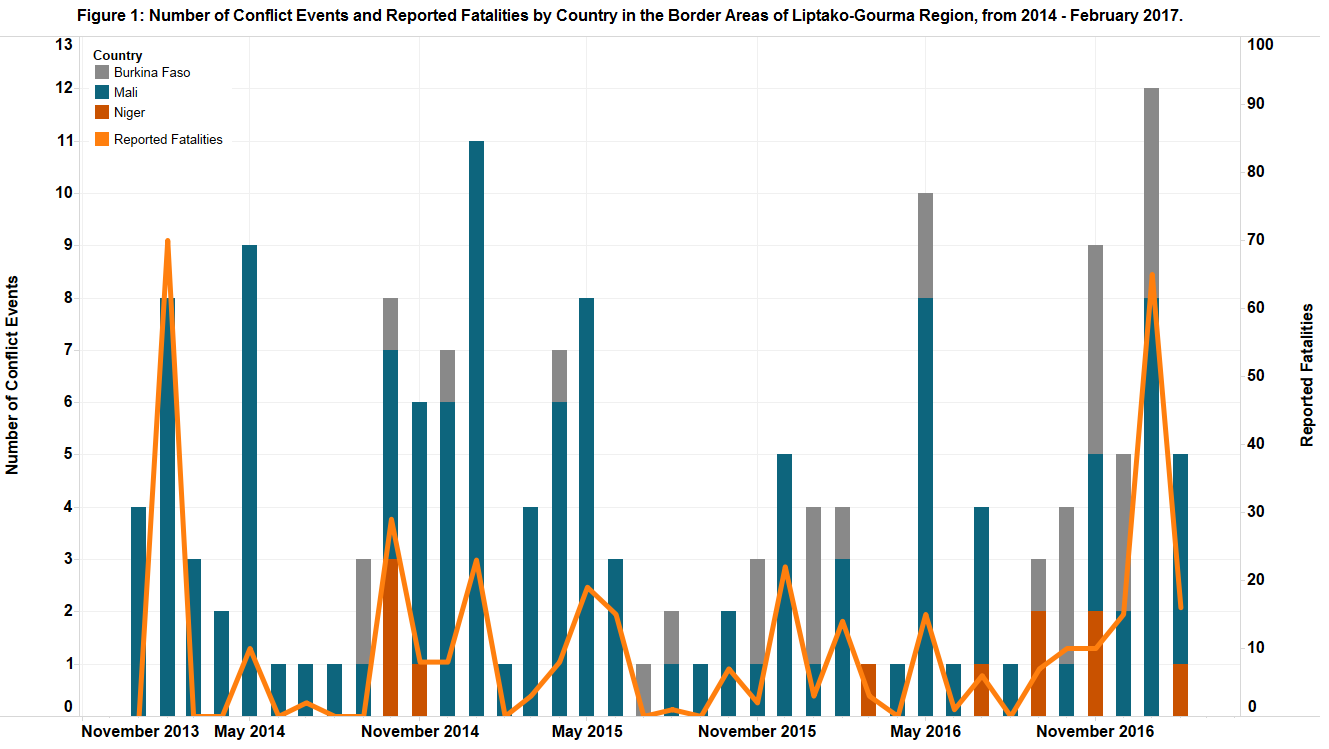

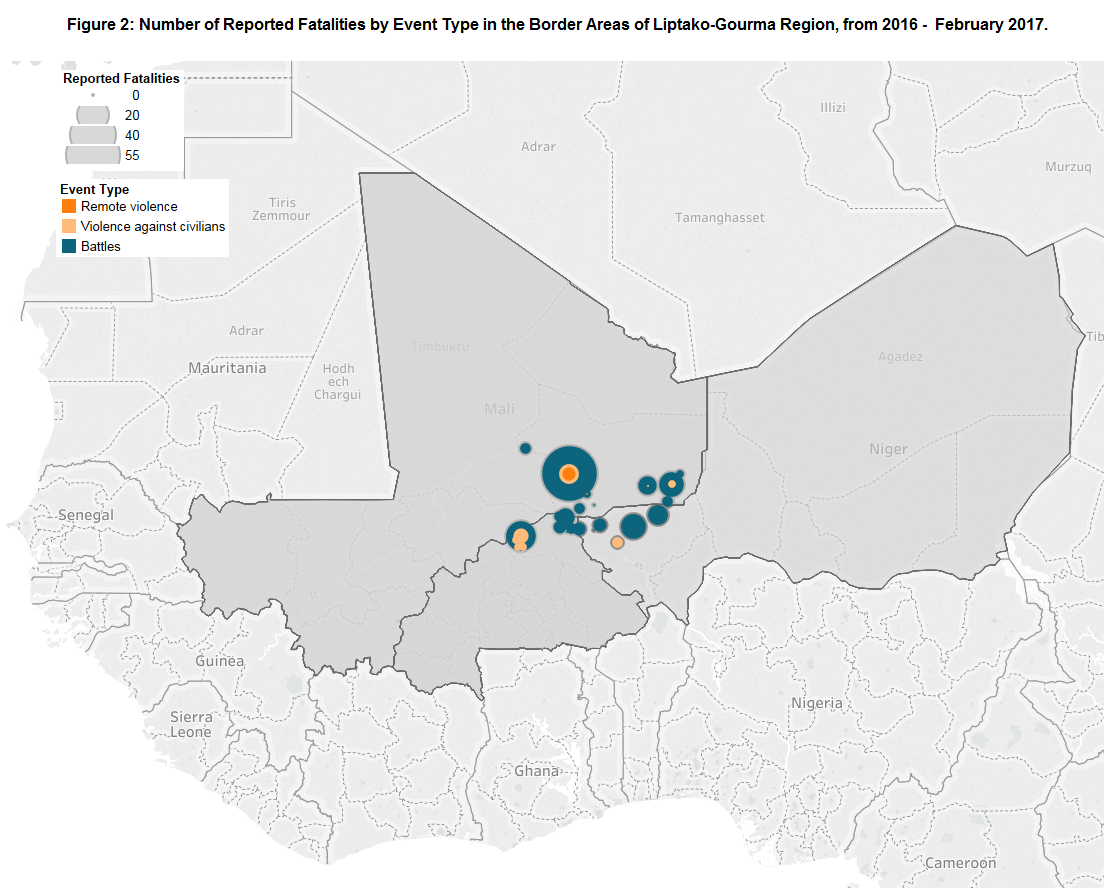

Although the Liptako-Gourma region has been the site of considerable violence since the beginning of the conflict in Northern Mali, the key shift in the period leading up to the creation of the new JTF was the growing spread of violence into Burkina Faso and Niger since the summer of 2015 (see Figure 1 and 2). This geographic shift has created a transnational issue presenting an increasingly difficult challenge to any individual government to solve. Furthermore, despite international deployment through Operation Barkhane and French jurisdiction within all three of these countries (BBC News, 14 July 2014), its operational presence is limited when forces are spread across an area three times the size of France (MENA Analysis, 7 January 2016).

By creating the JTF, the members of the LGA are recognizing that by removing the obstacle to cooperation presented by borders, solutions to the growing incidence of cross-border attacks in the region can be found. This is a clear example of how strategies adopted within the conflict with Boko Haram are spreading across the broader Sahel region. Niger in particular has gained considerable experience over the past few years by partnering with foreign militaries to deal with cross-border militancy. Besides its participation in the fight within Nigeria, Niger has also allowed Chadian military forces to be deployed in concert with its own in its eastern Diffa area since 2015, which has been the government’s primary site of conflict with Boko Haram. In both Nigeria and Niger, collaborating with neighbouring militaries has played a key role in limiting the advantages that borders present to militant groups. It now remains to be seen whether the LGA’s new JTF can provide the same benefits for the Liptako-Gourma region.