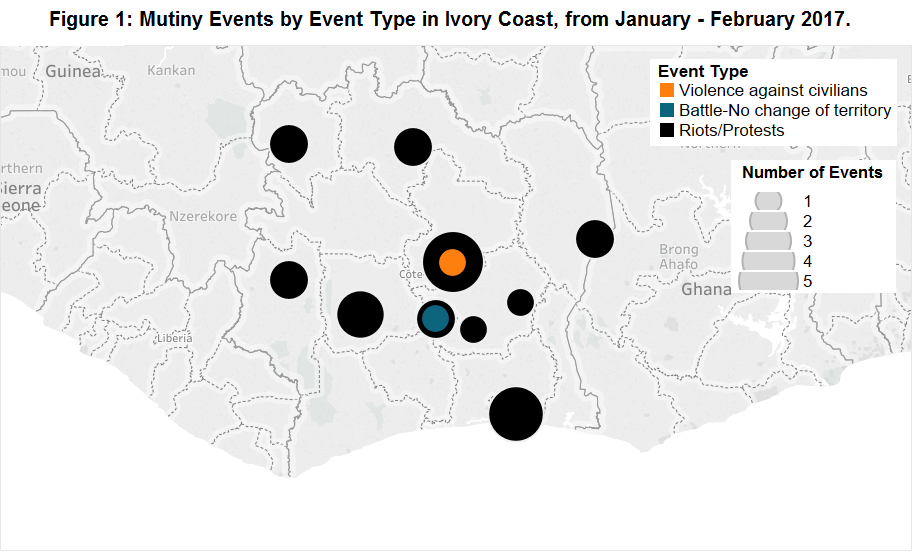

Ivory Coast witnessed a dramatic decrease in political conflict in February due to the apparent resolution of two mutinies which destabilised the country in January. The mutinies represent the biggest episode of political instability since the 2011 political crisis and exposed deep weaknesses in a country that has been lauded as a model of post-conflict reconstruction. The initial mutiny started in when soldiers took control of Bouake and demanded a pay rise and a lump sum of cash (The Economist, 14 January 2017). The mutiny then spread to Daloa, Korhogo, Daoukro and Man and finally the mutineers took over the army headquarters in Abidjan (see Figure 1).

The roots of the initial mutiny stretch back to Ivory Coast’s two civil wars. The starting point of the mutiny, Bouake, was the former capital of the rebel New Forces (FN) during the First Ivorian Civil War and the initial mutineers claim that their demands are based on promises made during the war against former President Gbagbo (The Economist, 14 January 2017). The mutineers further demonstrated their power by holding the Minister of Defence hostage (BBC News, 14 January 2017). In spite of the use of gunfire to intimidate government negotiators, the initial mutiny resulted in no fatalities and was resolved when President Ouattara pledged $19,300 to 8000 soldiers and dismissed the heads of the army, police and paramilitary gendarmes (BBC News, 9 January 2017).

Less than a week later, gendarmes mutinied in Yamoussoukro and clashed with military officers and the elite Republican Guard. The gendarmes had not been included in the financial bonuses given to the initial group of mutineers; they demonstrated to emphasize that they too suffered from sporadic pay and poor conditions (Daily Nation, 18 January 2017). In early February, Special Forces troops also seized the down of Adiake, again demanding the payment of bonuses (VOA, 7 February 2017). The government adopted a less conciliatory tone during the copycat mutinies, condemning the actions of the Special Forces and killing a number of the rebelling gendarmes in a gun battle in Yamassoukro (New24, 9 February 2017).

In spite of the harder line taken by the government, the military continues to exercise leverage over the Ivorian government. Though Ouattara was advised to reduce the size of the military after coming to power, the country has seen its military budget balloon from $350million in 2011 to $750million last year, with the mutiny adding another $64million to the bill (Africa Confidential, 3 February 2017; Reuters, 19 January 2017). This is due to large sections of the military being loyal to former FN commanders rather than the president. It has been speculated that former rebel leader Guillaume Soro may be behind the mutinies, designed as a means to consolidate his position as Speaker of the Parliament and position himself favourably in the race to succeed Ouattara in the 2020 elections (Africa Confidential, 3 February 2017).