The growing conflict with the Kamwina Nsapu (KN) militia in DR-Congo’s Kasai region has come to dominate international headlines, despite continued insecurity in DR-Congo’s Eastern provinces, and the threat of serious political instability following the collapse of the transition deal negotiated between Kabila’s government and the political opposition. Following the release of a video appearing to show Congolese security forces involved in mass killings of suspected members of the KN militia captured during operations against the group (Al Jazeera, 14 February 2017), international outrage and calls for an investigation drew considerable attention to the conflict. More recently, the beheading of more than 40 police by KN militia fighters during an ambush near Tshikapa (BBC, 27 March 2017), reports of as many as 23 mass graves being found by the UN across the Kasai region since August 2016 (BBC, 4 April 2017), and the killing of 2 UN Group of Experts members studying the conflict (New York Times, 28 March 2017) has only further drawn attention to the growing instability caused by the fighting. The question addressed here is what insights the data gathered so far can offer about the operations and aims of the KN militia and what this conflict might mean for the country going forward.

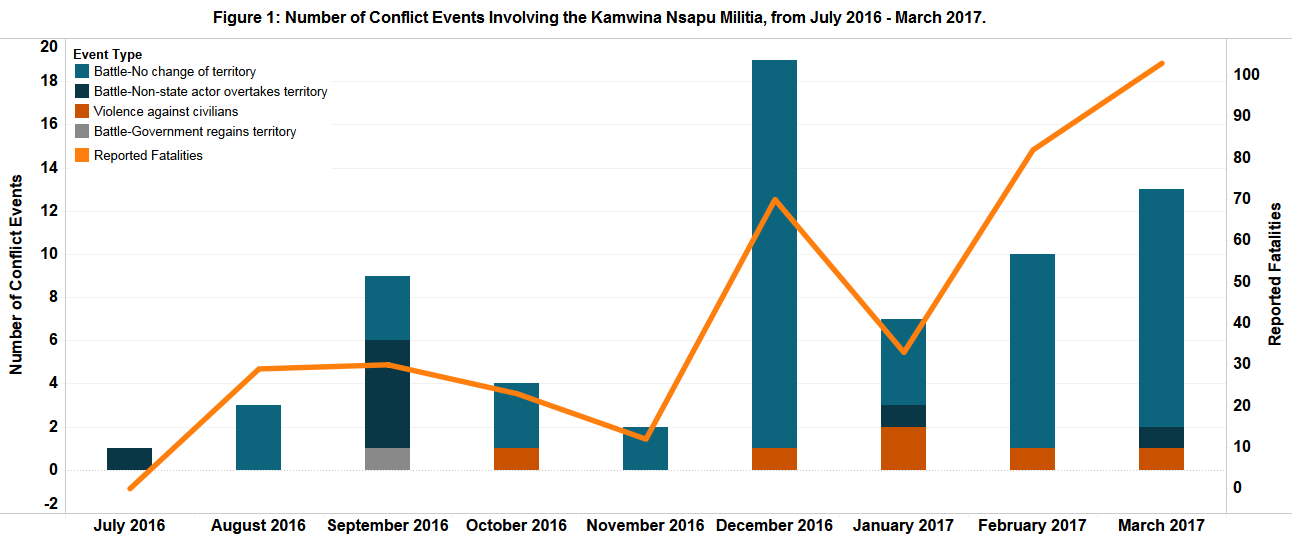

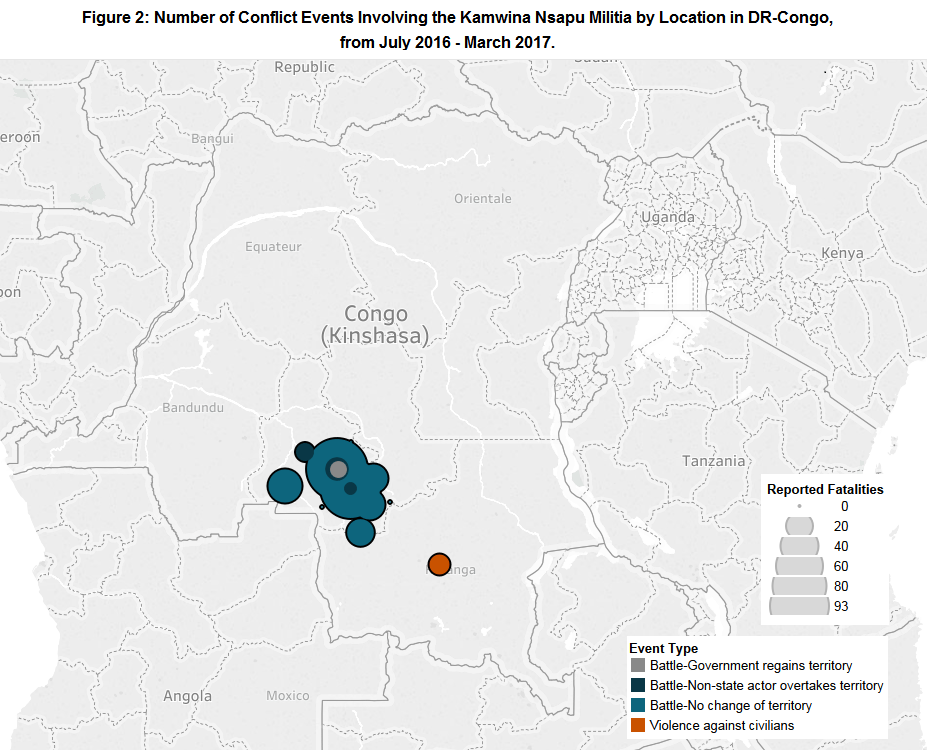

Unlike many of the smaller militia groups in the DR-Congo, the background for the KN militia is fairly well-understood. The group was initially created by Kamwina Nsapu (previously Jean-Pierre Pangi), who inherited a chieftancy in the Dibaya area from his father, over grievances with the central government. Although their operations allegedly go back as far as June 2016, their first major attack was carried out on August 8, 2016 in Tshimbulu, during which 9 people were killed and a number of symbols of government authority were burned, including police stations and a local electoral commission office. However, following this attack Kamwina Nsapu was killed during a clash with police on August 12, 2016, leading to a short lull in activity followed by a steep escalation in late September 2016 (see Figure 1). This included a major attack on Kananga, the capital of Kasai-Central, and the brief takeover of its airport by the militia before they were driven off by security forces (BBC, 24 September 2016). They also briefly occupied the town of Dimbelenge allegedly without a fight, burning police stations and a number of administrative buildings while also causing significant displacement of the population (Radio Okapi, 28 September 2016). Over the following months engagements continued between the militia and the security forces, including renewed assaults on Kananga and significant clashes around Tshikapa and Kabeya-Lumbu (see Figure 2), with a notable uptick in violence in December (see Figure 1).

In 2017, steady engagement between security forces and the KN militia has been reported weekly, with many of the most notable ones mentioned above, as well as high fatality engagements in Dibaya in early February and in Mwene Ditu in early March. Most recently a clash with security forces in the Kambamba area on March 28, 2017 left 18 militia fighters dead (Radio Okapi, 29 March 2017), while KN fighters killed at least 8 people, including police, during their capture of Luebo in Kasai Central (Radio Okapi, 1 April 2017).

With this context in mind, there are a number of things that make the KN militia unique compared to similar local armed groups, including the multitude of Mayi Mayi militias active in DR-Congo’s East. The first is the scope and scale of their operations, which have been reported across the Kasai region as well as in Lomani (see Figure 2) and have involved a number of successful captures of towns and cities (although they do not seem to be occupying territory) and the killing of large number of security officials. Another unique aspect is the focus and consistency of attacks against security forces compared to the relative lack of violence against civilians (see Figure 1), which is in line with the militia’s stated aim of achieving independence from the central government. There have also been reports of militia fighters attacking Catholic-run schools (Radio Okapi, 26 February 2017) in order to “free” the children studying there (News.va, 1 February 2017).

In terms of membership, the militia seems to have a large base of support, given that a number of its larger attacks, such as those targeting Kananga, were reported to have involved hundreds of fighters (Newsweek, 15 February 2017), despite repeated claims by security forces of large numbers of fighters killed or captured (French.China.org, 25 September 2016). These fighters also appear to be fairly young, as the UN has also accused the militia of using child soldiers (UN News Centre, 11 February 2017) and sources have been backing this finding since the early days of the militia’s operations (RFI, 14 August 2016).

Looking to Figure 1, it is clear that the conflict with the KN militia has markedly escalated over time, with December 2016 noting a drastic increase in both the number of events and reported fatalities. Over the last two months, events and fatalities increased. The fatality counts from February and March in Figure 1 also do not include a number of alleged civilian fatalities related to the security forces’ crackdown on the KN militia in Kasai.

With the recent mediated talks between Kabila’s government and the opposition having recently broken down following the collapse of the transition deal (Catholic News Service, 28 March 2017), the rising violence in the Kasai region is particularly troubling. Recent claims that Congolese security forces are engaging in atrocities in their operations against the KN militia could exacerbate political instability in the country, while a distracted central government may allow the security forces to take a hardline in quelling the uprising in Kasai, leading to further abuses and growing tensions.