In terms of number of events, March 2017 was the most violent month in Mali since early 2013, when France began Operation Serval against Islamist rebel groups in the north of the country.

The surge in violence is due to the activity of the newly formed Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal Muslimeen, otherwise known as Al Qaeda in Mali (AQM) (Bryson, 2017). The group is the result of a merger between Ansar Dine, Al-Murabitoun, Macina Liberation Front (MLF), and Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) with Iyad Ag-Ghali, the head of Ansar Dine, appointed as the group’s leader.

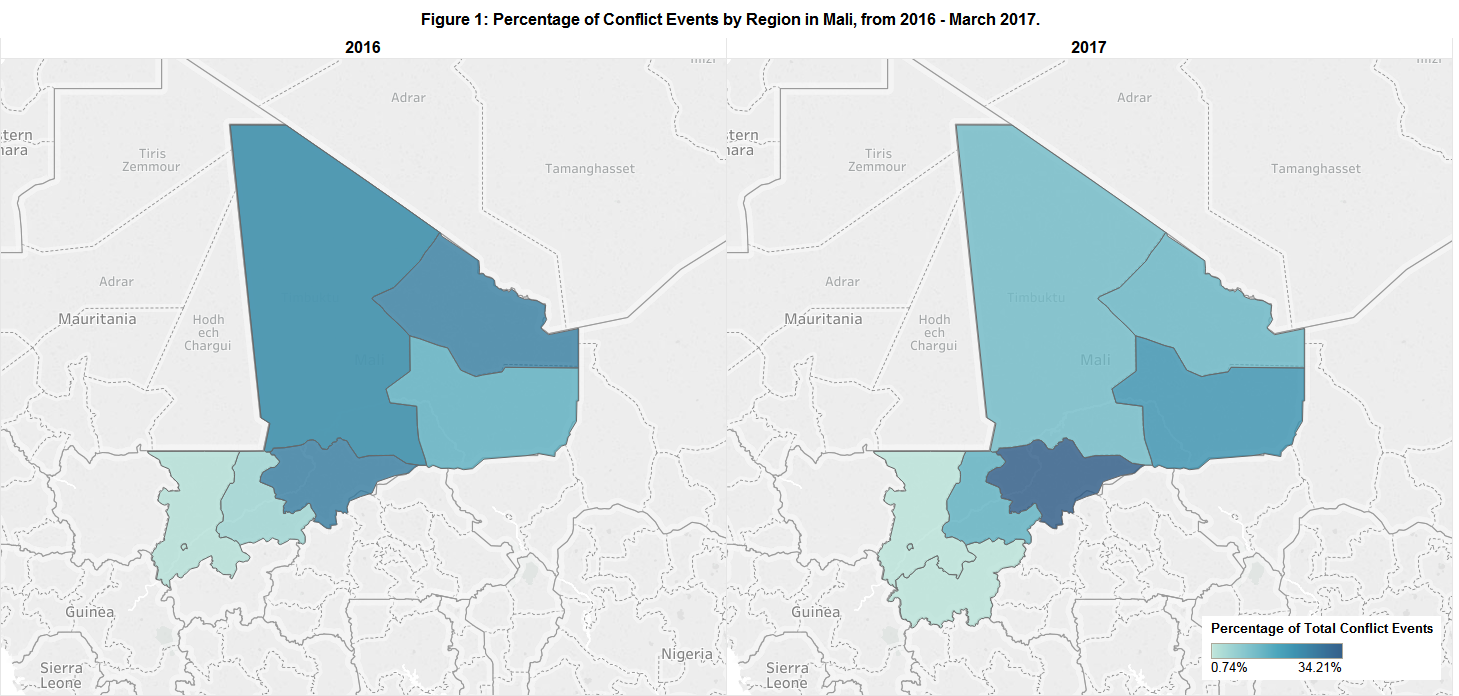

The merger represents a dangerous development to peace in Mali for several reasons. Firstly, co-operation between the various Islamist factions of Mali has previously led to the groups improving their ability to launch large-scale attacks far from their assumed spheres of influence. Increased cooperation and the sharing of resources between AQIM and Al-Murabitoun enabled the large-scale attacks on hotels in Ivory Coast, Burkina Faso and Bamako (Weiss, 2017). The merger of these groups will not just increase their resources but will give AQIM a foothold in a wider swathe of territory. The inclusion of the MLF has given Islamist rebels increased access to the more southern regions of Segou and Mopti, while retaining the traditional strongholds of Kidal and Timbuktu (ibid.). In this sense, the merger has been successful as a great percentage of conflict in 2017 is taking place away from the far north and in Mopti/Segou (see Figure 1).

A second issue is that this merger capitalises on Fulani grievances to unify ethnic politics with anti-state Islamist ideologies through the inclusion of the mainly Fulani MLF. The Fulani number approximately 20 million and are spread across nearly 20 countries in Western and Central Africa; they are frequently embroiled in herder-farmer conflicts and vilified as violent strangers in the states they inhabit (Fulton and Nickels, 2017; McGregor, 2017). Some Fulani joined the Tuareg-led Movement for Unity and Jihad in West Africa’s (MUJAO) rebellion in 2012. Since France’s Operation Serval expelled most Islamists from the middle-region, the Fulani have suffered from repeated abuses from the Malian security services (McGregor, 2017). The Fulani have also clashed with the majority Bambara ethnic group over grazing disputes (Reuters, 13 February 2017; Reuters, 20 November 2016). The MLF allied with Ansar Dine in 2016 yet Tuareg-Fulani tensions undermined the strength of the merger (McGregor, 2017). Violence from state forces and rival groups seems to have enabled other Islamist groups to secure a more stable merger with the MLF and Fulani fighters, curated by Al Mourabitoun and AQIM.

By targeting this group in the creation of AQM, Mali’s Islamist militants can further their reach dramatically and expand Mali’s conflict far beyond its borders.