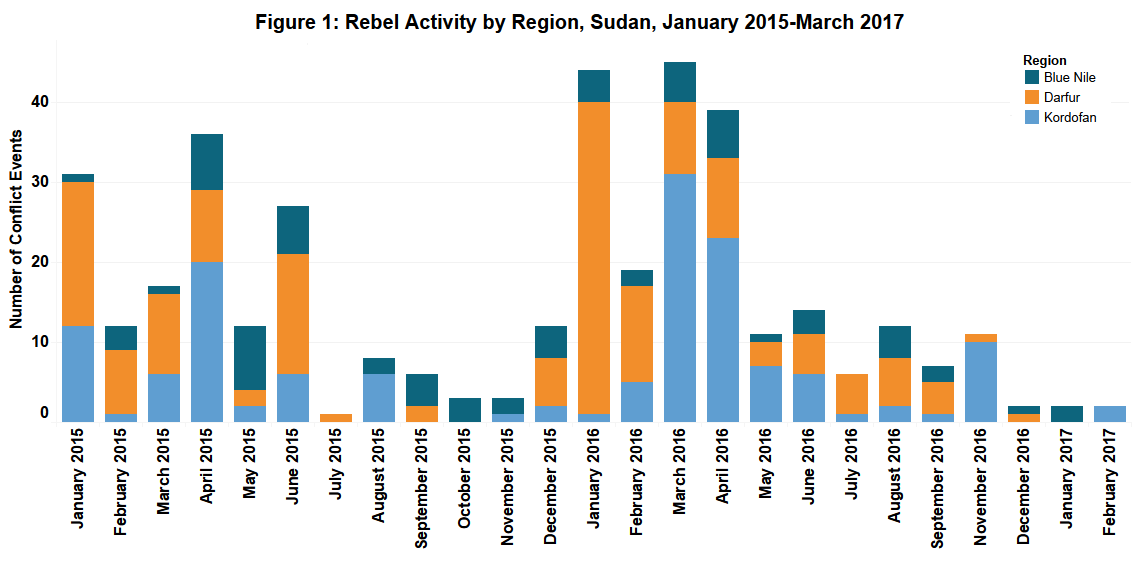

Sudan witnessed a decrease in violent political conflict in March which marked a continuation of falling levels of political violence in the country. The decrease in political violence seems to be related to the resilience of the ongoing ceasefire which encompasses a large number, but not all, of the active rebel groups. As a result, rebel activity has remained low since the start of the year (see Figure 1).

In October 2016, the rebel Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-North (SPLM-N), Sudan Liberation Army-Minni Minawi (SLA-MM) and Justice and Equality Movement (JEM) extended a ceasefire for 6 months in Oct 2016. A ceasefire had first been declared in October 2015 and was then extended in April 2016 (Sudan Tribune, 31 October 2016). The October 2015 ceasefire failed to contain the violence as government forces engaged in a concerted bombing campaign targeting the Sudan Liberation Army-Abdul Wahid’s (SLA-AW) territory in the Jebel Marra area of Darfur. It was during this campaign that chemical weapons used resulted in large civilian casualties (Amnesty International, September 2016). A similar large-scale offensive was launched in the SPLM-N’s territory of South Kordofan in March and April 2016.

In spite of past failures, the October 2016 ceasefire appears to have been adhered to by government and rebel forces, with March 2017 representing the first month without violent activity involving rebel groups since the latest ceasefire was announced.

Over the past month, both the government and rebel groups have given concessions in what appears to be a concerted effort to build trust between long-standing adversaries. In early March, the SPLM-N released 127 detainees, including 109 government soldiers (Nuba Reports, 6 March 2017). By mid-March, President Omar al-Bashir had issued a decree to drop the death sentences against 66 convicts from Darfurian rebel movements and pardon 193 others (Sudan Tribune, 17 March 2017).

In spite of these gestures, there are potential stumbling blocks. The most dangerous is the emerging factionalism in the SPLM-N. Last month, the group’s deputy chairman, Abdel-Aziz Hilu, resigned and accused Secretary General Yasir Arman of refusing to include the right of self-determination in the agenda of the peace talks with the Sudanese government (Nuba Reports, 31 March 2017). The Nuba Mountains Liberation Council (NMLC) endorsed Hilu’s demand for self-determination and decided to freeze the peace process (Radio Dabanga, 3 April 2017). SPLM-N Chairman Malik Agar decided to overrule the NMLC’s decision and create a temporary committee to force a consensus between the factions.

The rift within the SPLM-N does not just represent a threat to the peace process but also raises the possibility of inter-rebel violence. During the Second Sudanese Civil War, the government took advantage of factionalism within the rebel SPLA, leading to a south-on-south conflict which helped lay the foundations for South Sudan’s current civil war.