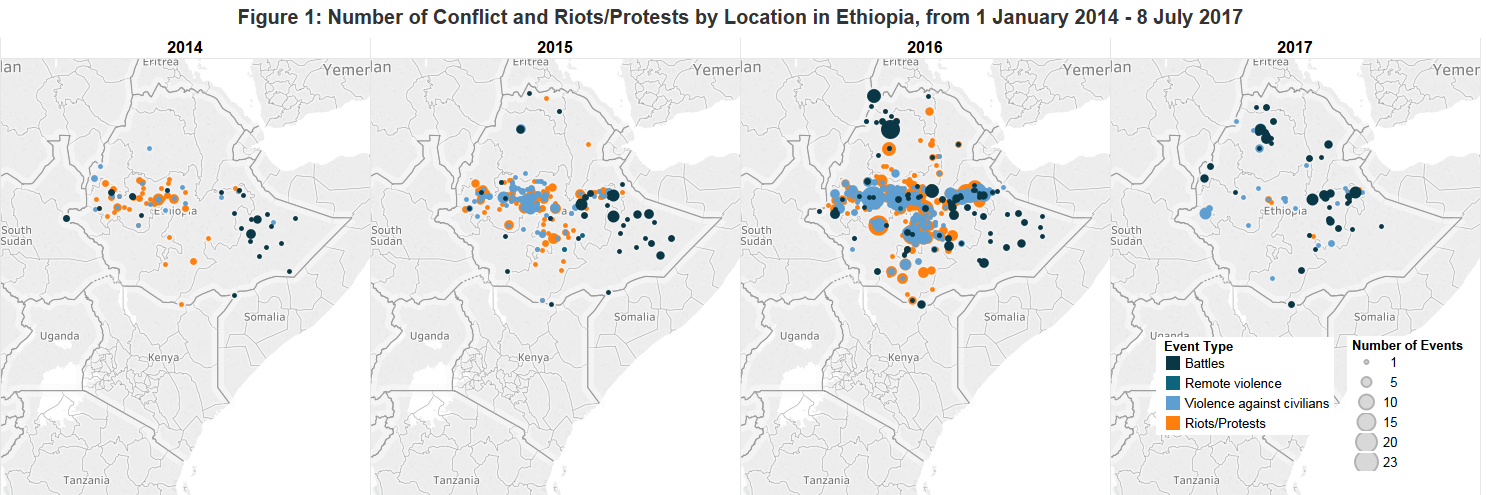

From November 2015, Ethiopia has experienced an unprecedented wave of popular mobilisation. The protests took place mainly in the Oromia region, spanning nearly 300 locations. They are generally seen as part of a movement that began in April-May 2014, when students across several locations in the region protested a plan to expand the boundary of the capital, Addis Ababa (hereafter, the Addis Ababa Master Plan). The 2014 protests, led by university students, were comparatively small and situated in the Western part of Oromia (see Figure 1). From November 2015, the demonstrations quickly gained momentum, and farmers, workers and other citizens soon joined the students in collective marches, boycotts and strikes (see ACLED, June 2017 for a more detailed background on the roots and dynamics of the protests).

Despite the government’s suspension of the Addis Ababa Master Plan in January 2016, the protests continued and expanded to other regions, such as Amhara and the SNNPR. The Amhara community joined the Oromo protests in August 2016, after a fatal clash between security forces and Amhara residents over the Wolkayt district’s identity issue ignited regionalist grievances (African Arguments, 27 September 2016). The continuation of the protests revealed widespread suspicion of the Ethiopian regime and enduring grievances among different ethnic groups, particularly in the way federalism is implemented, and in the way power and resources are shared. The Ethiopian government’s unrelenting use of lethal force against largely peaceful protesters since November 2015 has played a major role in bolstering a shared sense of oppression among the Oromo and other ethnic groups. Available data collected from international and local media since November 2015 points to more than 1,200 people reported killed during the protests. Approximately 660 fatalities are due to state violence against peaceful protesters, 250 fatalities from state engagement against rioters, and more than 380 people killed by security forces following the declaration of the state of emergency on 8 October 2016.

The state of emergency was declared after government violence at the Irecha festival in Oromia led to a “week of rage” among the opposition. The move cemented the government’s commitment to repression rather than dialogue (The Guardian, 20 October 2016; Amnesty, 18 October 2016). The state of emergency imposed tight restrictions that have since successfully curbed the protests. However significant developments have occurred in parallel, pointing to persisting discontent in Ethiopia.

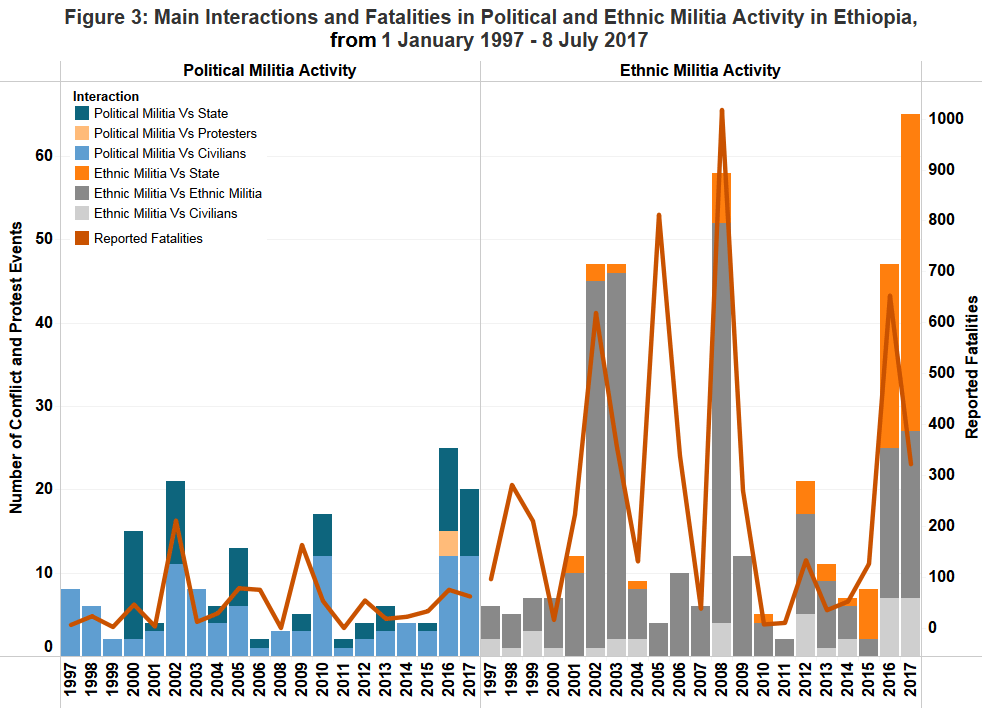

First, the significant reduction in riots and protests accompanied an increase in battles involving security forces and foreign-based rebel groups, and in political and ethnic militia activity. Though the link between the protesters and the various armed groups remains unclear, these trends point to an escalation from peaceful unrest to an armed struggle taken up by local armed militias and rebel movements united in their aim to remove the government.

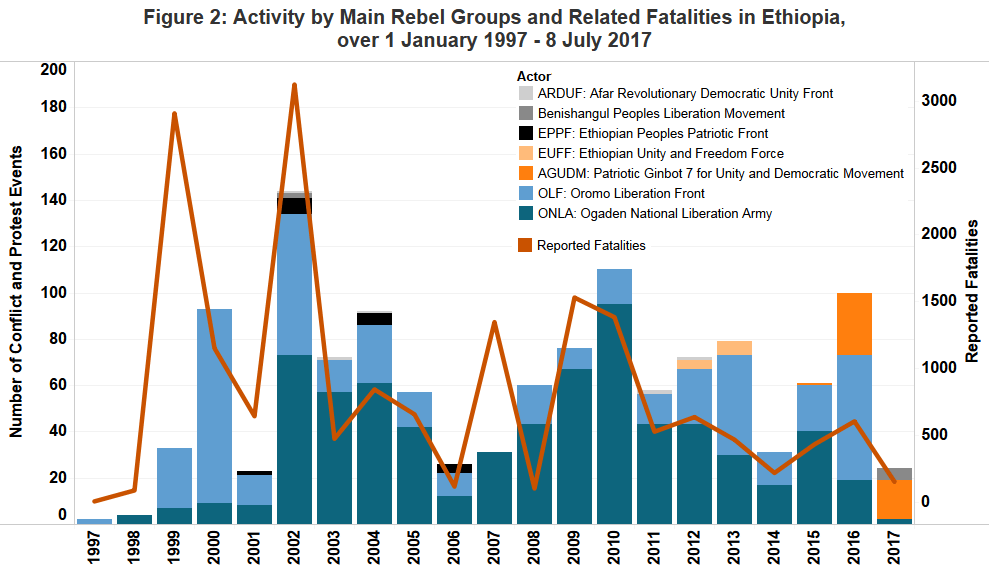

The ACLED dataset shows that rebel activity in 2016 was at its third highest since 1997 (see Figure 2). Rebellion reached unprecedented levels in Oromia and Tigray, led by the OLF and the AGUDM forces respectively; and in Amhara, rebellion led by the AGUDM forces resurged after two years of inactivity. So far in 2017, AGUDM has represented the most active rebel front in the country. The group significantly stepped up its attacks in June 2017, confronting government forces on several fronts in the Amhara region’s Gonder zone, and claiming a rare attack in Addis Ababa on a government ammunition depot. The movement’s leader recently announced that AGUDM’s attacks would not subside. Other rebel fronts, however, have been relatively inactive in 2017. As of end June, no attack had been claimed yet in 2017 by the OLF for instance.

In parallel, militant activity has significantly increased in Oromia and Amhara in 2017 (see Figure 3). Since January 2017, large numbers of the Oromo community have risen up against a marked increase in attacks and human rights violations in Oromia by state and paramilitary forces, such as the Liyu police. Data collected shows nearly 40 clashes between the two parties along the border with the Somali and Afar regions between 1 January-8 July 2017, resulting in around 170 fatalities. This compares to only six clashes between Oromo militias and state forces during the protest period. The Oromo community identifies the increased activity by the Liyu police as a way for the government to usurp Oromo lands and further quash dissent (Opride, 5 March 2017). The assignment of federal soldiers to all members of the Oromia regional police in May after suspecting some of them of supporting Oromo militias in the recent clashes, revealed the government’s continued control of the country’s security apparatus. In Amhara, unidentified armed groups also engaged in various clashes with state forces and executed no less than 14 bomb and grenade attacks, mainly targeting state officials, between 1 January-8 July 2017.

Secondly, the ruling party’s continued domination since the declaration of the state of emergency and failure to engage in a dialogue with the protesters underlines its lack of interest in addressing the grievances that motivated the protests in the first place. This suggests that there is a strong possibility of demonstrations resuming once the state of emergency is lifted at the end of July 2017.

Several developments since the declaration of the state of emergency have reinforced the perception of government oppression among the protesters. Chief among them is the implementation of the state of emergency’s tight restrictions, which has led to hundreds of new fatalities and arrests, as well as to a pervasive state control of Internet access and use. Many people have been arrested on the basis social media posts perceived as inciting violence for instance, while the government imposed prolonged periods of nationwide Internet blackouts to control students during national examinations (Tadias Magazine, 13 June 2017; Africa News, 11 June 2017). The ruling party’s refusal to allow an independent probe into the protests has also fuelled a loss of hope among the protesters for a better form of government, which respects peoples’ basic rights. This is despite the many international calls for the establishment of a fair accountability process, including by the UN and by members of the European Parliament (IPS, 17 April 2017; Africa News, 11 July 2017).

Other oppressive state practices in 2017 have also led to several punctual protests, most of which were severely repressed. In Oromia, people protested in March 2017 against violence by the Liyu police. Students also protested in Ambo in June 2017, after the Ethiopian education authority revealed a plan to re-arrange the Oromo alphabet. Police arrested 50 students, including two whom died from severe beatings received during their transfer to prison facilities. In Amhara, people protested in April 2017 against the planned demolition of thousands of houses by the government, and were fired on by federal military troops (ESAT, 23 March 2017). Finally, at various international sporting events in early 2017, several Ethiopian athletes have protested the ruling party’s inability to embrace ethnic and religious diversity, by refusing to wave the current starred Ethiopian flag to celebrate their victories (African Arguments, 6 March 2017).

Politically, the several changes introduced to the Prime Minister’s Cabinet and to the leadership of the party representing the Oromos within the ruling coalition in the course of 2016 suggested only minimal ideological repositioning and thus did not convince the protesters. The government’s introduction in July 2017 of a draft bill to review the status of Addis Ababa represents the first attempt at credibly addressing the Oromo protesters’ grievances politically, by giving concrete meaning to Oromia’s constitutionally-enshrined “special interest” in the capital. However, there is still a possibility of future unrest if dissensions are not solved with its detractors, particularly among the Oromo nationalists (QZ, 6 July 2017; Global Voices, 7 July 2017). A recent plan to establish an oil venture in Oromia has also been seen by the ruling party as a way to address the protesters’ economic grievances (Bloomberg, 21 June 2017). Building on these overtures could lead to advancements in negotiations between the protesters and the government, and reduce the likelihood of future disruptions.