On 19 December 2016, President of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DR-Congo) Joseph Kabila’s constitutionally-mandated two-term limit expired. Shortly after this deadline passed, the Congolese Catholic Church mediated the signing of the Saint Sylvester Agreement on New Year’s Eve in order to defuse the political crisis and allow for a peaceful transition (Deutsche Welle, 2 January 2017). One of the main components of this agreement was the creation of a transitional government meant to preside over elections, which had been delayed repeatedly and originally scheduled for November 2016, to be held by the end of 2017. As part of this agreement, President Kabila agreed to appoint a member of the opposition to head the transitional government. This occurred on 7 April 2017 when Kabila selected Bruno Tshibala, former member of the Union for Democracy and Social Progress (UDPS) which is the DR-Congo’s main opposition party and part of the opposition coalition the “Rassemblement” or Rally of the Congolese Opposition (OCR), to become the country’s new prime minister (Al Jazeera, 7 April 2017).

Since then, there have been several developments in Congolese politics which have complicated and deadlocked the political situation. The first is the death of veteran Congolese opposition leader and head of the UDPS, Étienne Tshisekedi. Second is the expansion of the Kamwina Nsapu conflict in the Kasai region, renewing international concern over insecurity in the DR-Congo. The third is the government’s repeated dispersal of periodic opposition demonstrations calling for the president to step down and for elections to be held.

Tshisekedi’s death was a significant challenge for the political situation in the DR-Congo as he was the nominal leader of the fragmented opposition to Kabila’s rule. His death caused significant instability within the UDPS, which has since seen infighting despite Tshesekidi’s son, Felix, taking over at the head of the party (Reuters, 4 March 2017). Within this context the appointment of Tshibala– who had recently left the party– as the new prime minister has been seen as the government exploiting these tensions to further divide the UDPS. On the other hand, the death of Tshisekedi has also opened up room for new leaders to step up to challenge Kabila (African Arguments, 15 June 2017), such as Moïse Katumbi, who was governor of the former province of Katanga (one of the country’s largest and richest) for 8 years and has significant political clout.

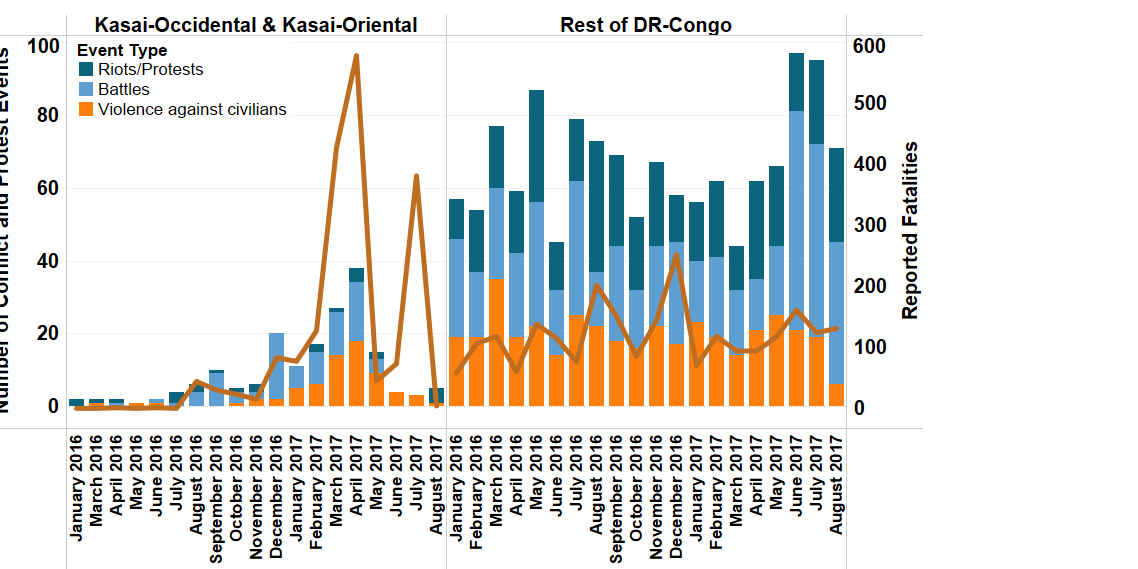

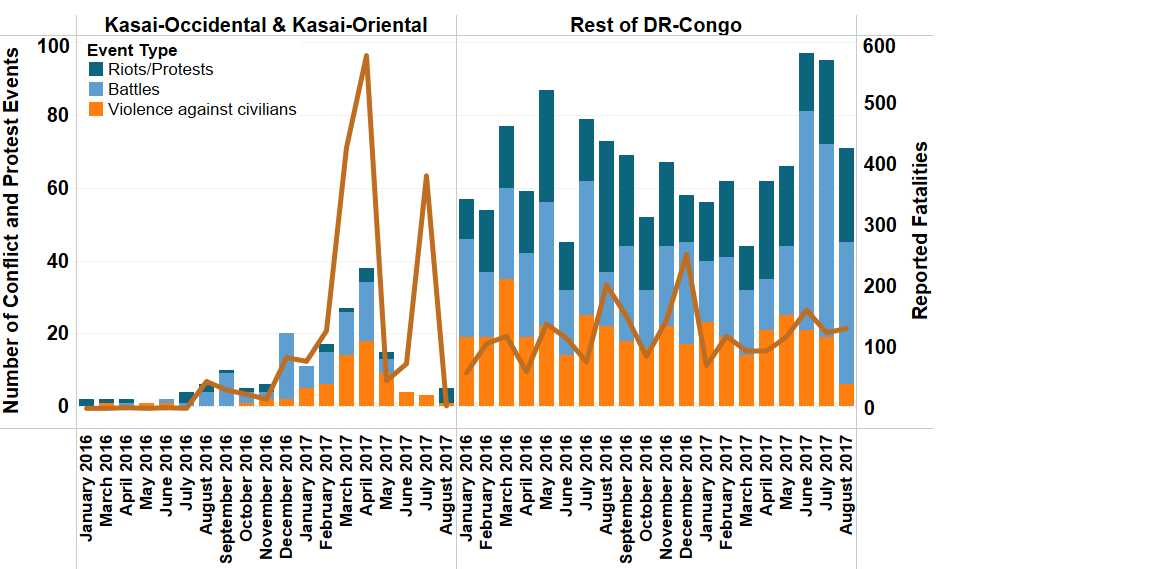

Figure 1: Number of Conflict Events and Reported Fatalities by Event Type and Location, January 2016 – August 2017

Despite this, the various factions within the opposition remain largely divided, and it is doubtful whether they can effectively mount a challenge to Kabila’s strategy of using delaying tactics to put off giving up power.

Ambiguous statements by Kabila himself (AfricaNews, 4 June 2017), and the country’s electoral commission head, that elections may not be held this year seem likely to reinforce this outlook (Reuters, 9 July 2015).

While the political situation has evolved, conflict in the Kasai region since late 2016 (see Figure 1) has further muddied the waters and pulled away international attention. The conflict has been riddled with accusations of atrocities committed, with mass graves and videos showing alleged killings on both sides leading to international condemnations (New York Times, 28 July 2017). This included the killing of two UN Group of Experts members who had been in the Kasai region to investigate the conflict, with both sides accusing the other of the killings (New York Times, 23 May 2017). And though seemingly a largely decentralized movement with no identifiable leader, a self-proclaimed Kamwina Nsapu spokesman added the implementation of the Saint Sylvester Agreement as part of their demands in an interview, alongside the local concerns which prompted the initial fighting (ICG, 21 March 2017). Despite a significant drop in fighting since June 2017, the large-scale displacement caused by this conflict, and its ability to pull international focus away from the political deadlock, can be seen as diminishing pressure on the Kabila government over the transition when it’s needed most.

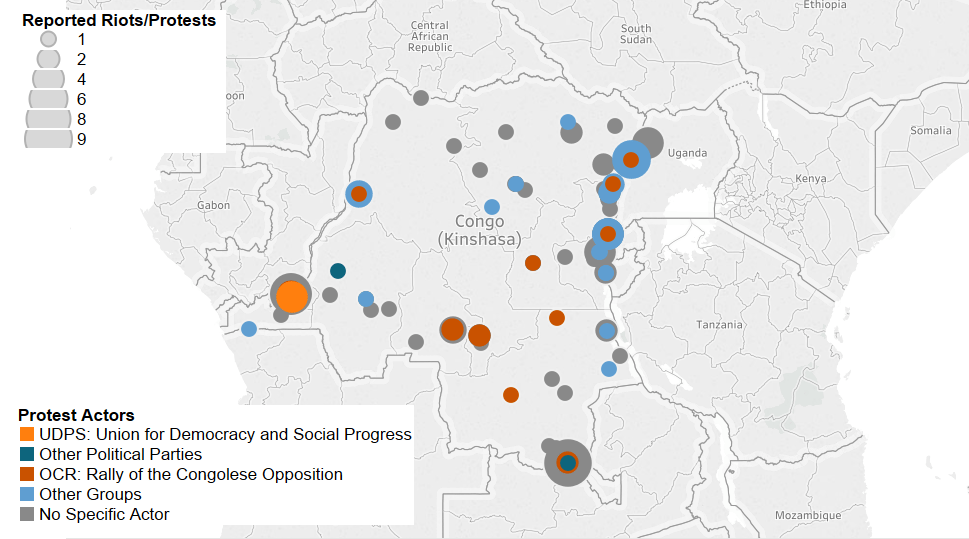

Pressure remains as the OCR has continued to organize protests throughout the country (see Figure 2), albeit fewer than in previous years. The two most notable in 2017 occurred in April, including a national strike called on 3 April which was well-attended in the capital and cities (France24, 3 April 2017) of Goma, Kananga, Mbuji-Mayi and Lubumbashi. All demonstrations associated with this strike were quickly dispersed by police however. Following this, a second nation-wide day of protest on April 10 saw demonstrations in at least 10 cities despite a government ban (Deutsche Welle, 10 April 2017), almost all of which were dispersed by police with varying levels of violence. This coincided with a peak in violence in the country, a large part of which can be attributed to the conflict in the Kasai region (see Figure 1).

These demonstrations have been more subdued than those witnessed in previous years: protests in December 2016 resulted in as many as 40 deaths in the run up to Kabila’s term limit expiring; and in January 2015, at least 27 were killed after a proposed law was announced extending Kabila’s term limit until a national census could be held. The significant numbers of deaths during protests over the last two years, combined with the fragmentation of the opposition, seem to have deterred significant further action by the opposition on this front. The actions of the government have not gone unnoticed by the international community however. Over the past year, sanctions have been passed by the US, EU and others targeting police and officials involved in violence against protesters and other abuses (HRW, 1 June 2017), as well as members of the government seen as delaying the vote (Al Jazeera, 11 July 2017). Whether this pressure will have a serious effect remains to be seen.