As Kenya heads for another election on 17 October to decide who will be president, we review how the August election passed. Concerns are growing that many of the local close elections will be re-contested, especially given the rate of incumbent overturns resulting from the August poll.

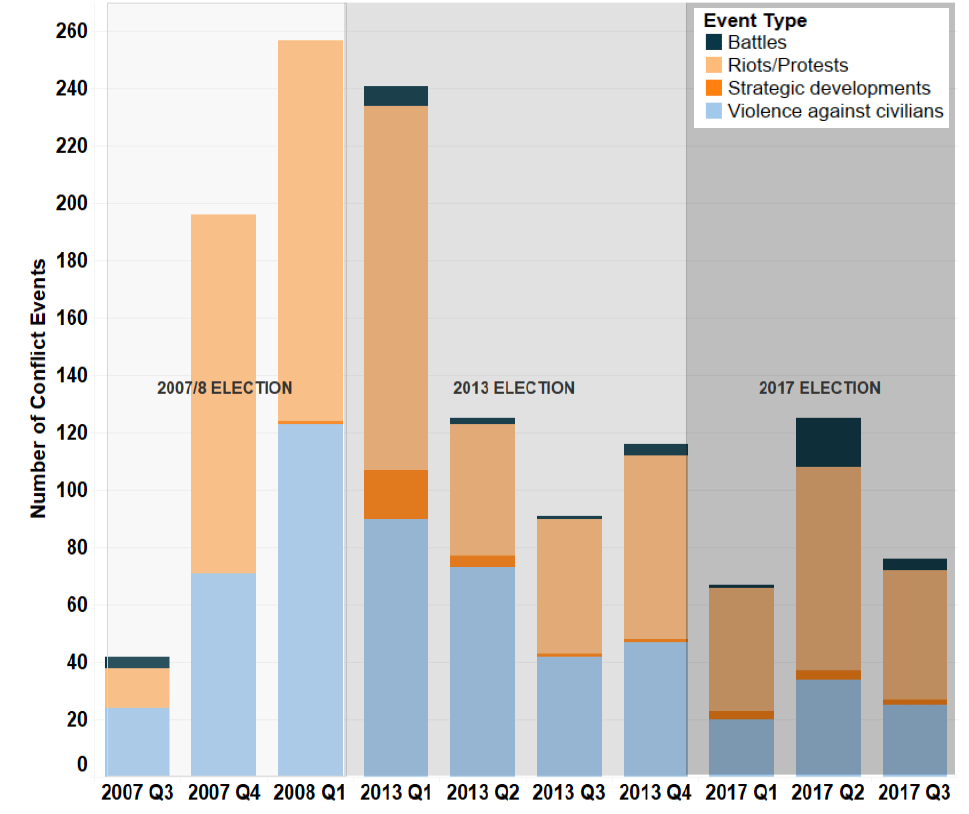

Overall, the Kenyan election was successful in myriad ways: the expected onslaught of violence never occurred: a limited and brief increase in activity occurred in key urban districts after the release of national level results (see Figure 1). President Kenyatta won the August contest by more than 10%, until those results were nullified by the Supreme Court.

Kenyans vote for six different positions when they go to the polls: president, governor, senator, MP (for county), women’s representative (for county) and Members of County Assembly (MCA). Previously, Kenyans voted for the initial three positions. Because of the increase in constitutionally mandated positions, the presidency is less important now than it ever has been.

Instead, the positions of power in Kenya’s system are the office of the governor and the MCA (for less wealthy candidates, as they will receive state redistribution funds). In line with calculations by Nanjala Nyabola in August, the variation in power and positions has led to more intense competition for these seats: 15,082 people vied for positions in the August elections across all six levels. Specifically, the number of MCA candidates grew by 22% from 2013 levels.

As Hannah Waddilove notes in African Arguments, this competition led to an overturn of incumbent held seats unlike any experienced across recent African elections: over half of Kenya’s incumbent governors, 62% of MPs and 79% of women representatives lost their seats in August. The changes were most apparent in areas that supported the opposition coalition (NASA). There is little consolidation of the NASA coalition at the local level, as members of different opposition parties within the coalition competed for the same positions. Given this level of competition at the local level, and Kenya’s typically highly localized political violence patterns, this election indicates that violence is neither necessarily nor particularly likely under periods of intense competition.

However, there other explanations for the low levels of election violence. Most election violence in 2007/8 was because of the political faultline between the Kikuyu affiliated political groups, and those affiliated with Kalenjin political players. This was not the faultline of the 2013 and 2017 elections. Seen from this perspective, violence was never likely because the strongest parties are already in power, and have other means to get their preferred ends. The NASA coalition is wary of any association with violence, as it will affect their perceived moral legitimacy and ability to co-opt internally and internationally.

Waddilove also notes that the Presidential election was close in only 12 of the 47 counties. That may be due to bloc voting that is common when parties have built support in districts, but it may also be due to widespread inconsistencies in the presidential poll. The Supreme Court of Kenya has not yet spoken in detail as to its decision to demand a new President poll, but the reasoning relates to irregularities in the electronic system designed and implemented by the IEBC (Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission). Both the commission and its chief- Ezra Chiloba- were singled out by the Supreme Court, who pointedly did not accuse President Kenyatta’s Jubilee coalition from being involved. Whatever the case, if the election was close in 12 of the 47, and several others within the remaining 35 are core constituencies of the Jubilee coalition, it stands to reason that oversight was strong in the competitive districts and cheating- if it occurred- happened in areas that were expected to be pro-NASA, and may have been done in ways that were not observable to those on the ground.

The vote will be watched carefully from several angles- from the technical side to the local reporting side. However, this is now a contest of mobilization. Here, Kenyatta has the most to lose: any cheating that did occur did not save some Jubilee affiliated coalition governors, MPs or Women’s representative who lost their seats. Although Jubilee won more governorships than in 2013, several of the losing incumbents are demanding recounts. Depending on who won or lost those seats, there could be a groundswell of support to push Odinga over the line and contest lost opposition-governor races. This could a viper’s nest for Kenyatta to occupy as he goes into a new contest with his local affiliates knowing that he did not save many of them, and others knowing he looks out for himself over his local partners.