Since August 2017, activity by the Islamic State in Libya has begun to increase with fears that they are starting to regroup and stage a comeback (Bloomberg, 12 September 2017). Militants are reported to be operational through a “desert army” that was established after being pushed out of Sirte last year by Misratan militias. If Islamic State militant activity is beginning to mount, what threat does it pose and to whom? And how do the patterns of violence compare to their most active periods of fighting in Libya?

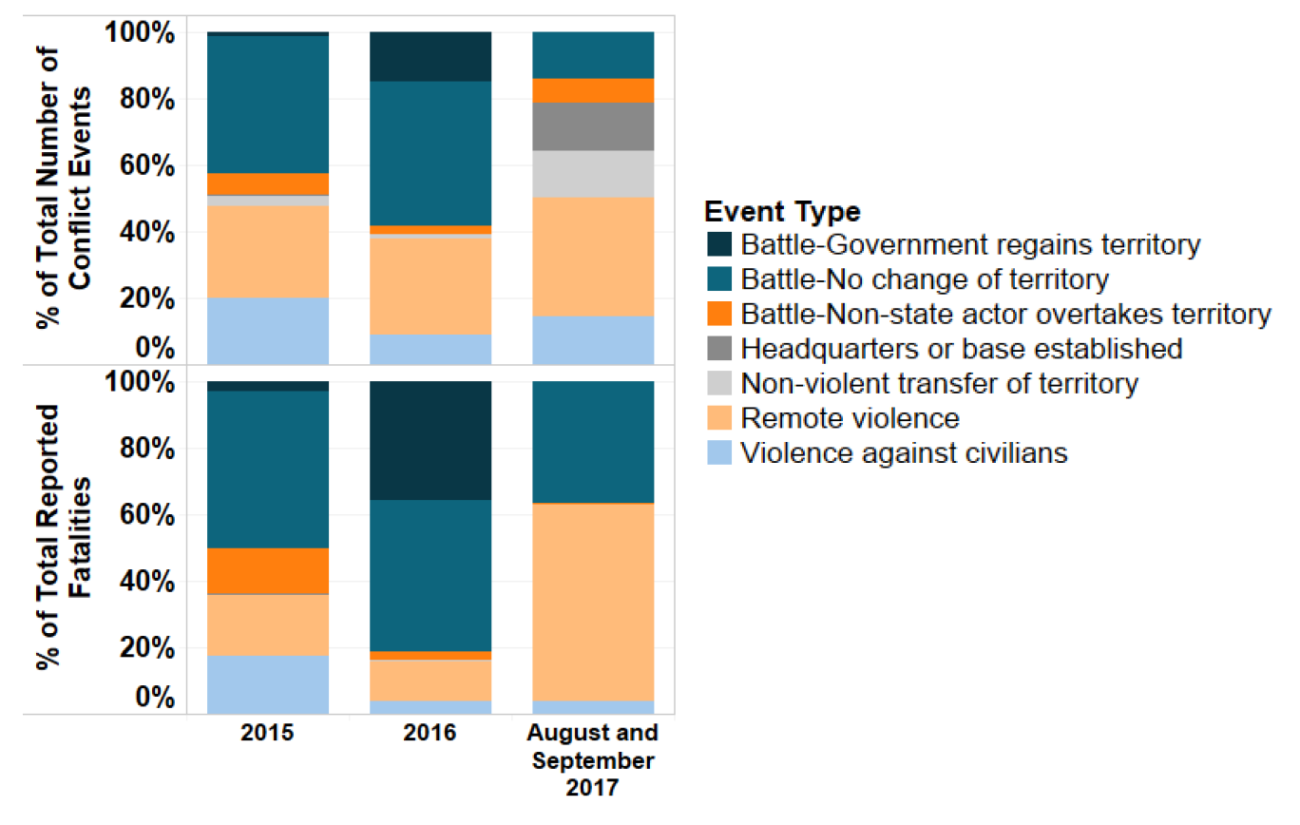

First, their operational capacity appears to be nascent. AFRICOM estimated that fighter numbers declined from around 6,000 in 2016 to around 500 active in Libya today (VOA News, 29 September 2017). On 22 September, U.S. military forces carried out precision airstrikes against IS locations killing 17 militants. As such, remote violence made up 36% of conflict activity in August and September, compared to 29% and 28% respectively in 2016 and 2015 (see Figure 1). Remote violence was the most lethal conflict form in August and September, accounting for 60% of all fatalities involving IS. However, only one of these events was perpetrated by IS militants as two policemen and 2 LNA soldiers were killed by a VBIED near Nawfaliya.

Ground battles have been reported, the most significant being a violent operation in which nine Libyan National Army soldiers were beheaded at the Fuqaha checkpoint in Al Jufrah on 23 August and an IS-manned checkpoint was established near Abu Grein on 29 August. At present, almost all of the activity has been reported in the Sirte region. Other activity has involved establishing checkpoints and a few instances of civilian-targeted violence against Salafists, though fatalities have remained low. So far, forces supporting the Government of National Accord (GNA) have not engaged with IS militants, with the LNA being the main targets.

If the rise of IS is to continue in Libya, it could disrupt and divide the negotiating parties within the Libyan political agreement. In 2015, Frederic Wehrey highlighted the “sinister synchronization between Operation Dignity attacks on their [Misratan forces] western flank and Islamic State bombings in and around Misrata” (Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 24 June 2015). Fast forward to 2017 and efforts at establishing a constitutional referendum and timeline for elections have been timetabled by U.N. Special Envoy to Libya, Ghassan Salame (STRATFOR, 21 September 2017). As deadlock in the fighting pushes emphasis on to institutional political developments, Gen. Haftar’s position as the head of the Libyan military is once again called into question. The LNA conducted sweeping patrols around Sirte in late August, likely to ensure protection of key oil fields. This put them within 10km of forces supporting the GNA (War is boring, 15 September 2017) and could ignite fresh tensions between the LNA and GNA-forces recently witnessed in southern Libya. Should fighting flare up around Sirte or the south again, the emergence of IS may well act to stall or divide negotiating parties and further complicate the wider dynamics of civil violence.