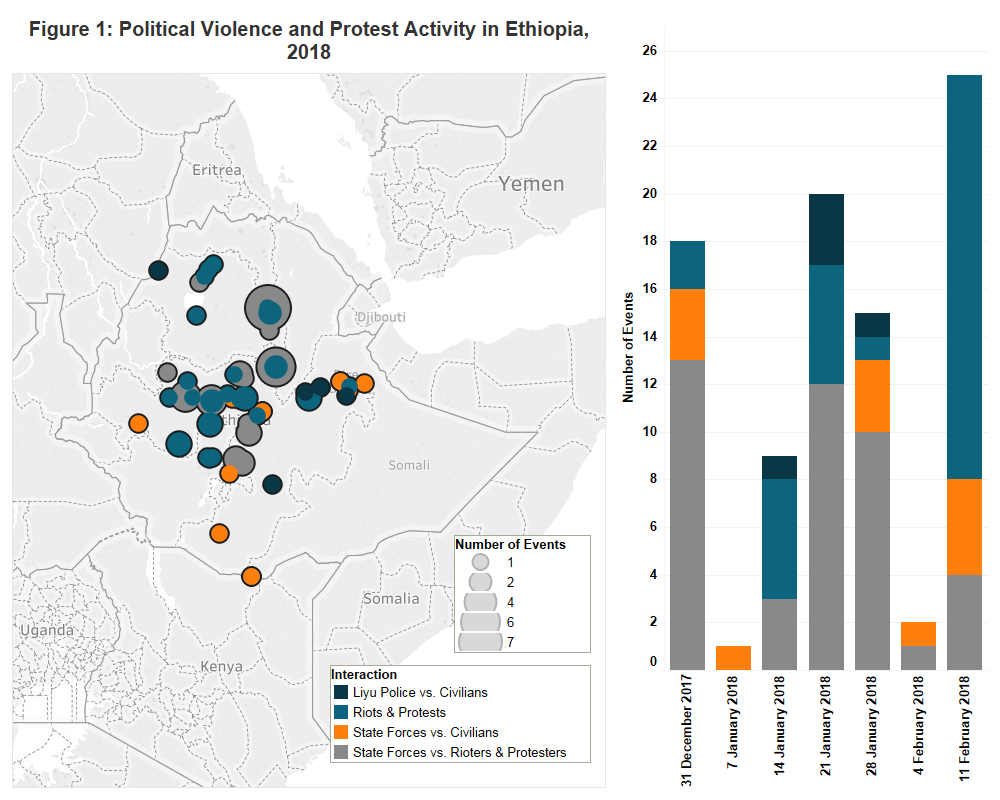

Signs of a political thaw in Ethiopia have taken a sharp reversal. Despite the government’s amnesty of 6,000 political prisoners in January, protests against the Tigray-led regime in the Oromio Region have spread into the Amhara and Southern Nations regions (Financial Times, 17 February 2018) (see Figure 1). That amnesty came after ‘political re-education’ in prisons, which does not look like it was successful.

Anti-government riots and protests surged last week. The recent protests have called for the further release of political prisoners, namely Bekele Gerba of the Oromo Federalist Congress (OFC). Security forces were noticeably absent from engaging protesters compared to previous weeks, but non-protesting civilians in Oromia were still subject to attacks by state forces, concentrated in areas that had witnessed protests.

Bowing to growing pressure, the ruling Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) released the three years-held politician on 14 February (News24, 14 February 2018). The perceived capitulation of the government has led to suspicions of discord within the regime. The abrupt resignation of Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn on 16 February is further evidence of this turmoil.

Following Desalegn’s departure, the government instituted a six-month state of emergency immediately citing “ethnic-based clashes” and “chaos” (New Vision, 17 February 2018). With this second implementation of martial law since late 2016, Ethiopia’s defence minister has been eager to insist their measures do not constitute a “military takeover” and have been implemented to hasten an orderly transitional government (The Herald, 19 February 2018). The US State Department and European Commission have criticised the declaration. It is yet unclear if these ministries will use aid money to leverage the government, a sum which reached $454 million and over €91 million in 2017, respectively (Washington Post, 31 August 2017) (European Commission, 8 December 2017).