Many believe Syria constitutes the worst crisis in a decade. Indeed, the UN Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner has stopped counting fatalities in 2014,[1] the amount of US (2017) and Russian (2016) airstrikes is unprecedented[2] and after distinct crises such as Sinjar, Khan Shaykhun new ones continue to arise (Eastern Ghouta, Afrin). How ‘bad’ is Syria in a comparative perspective?

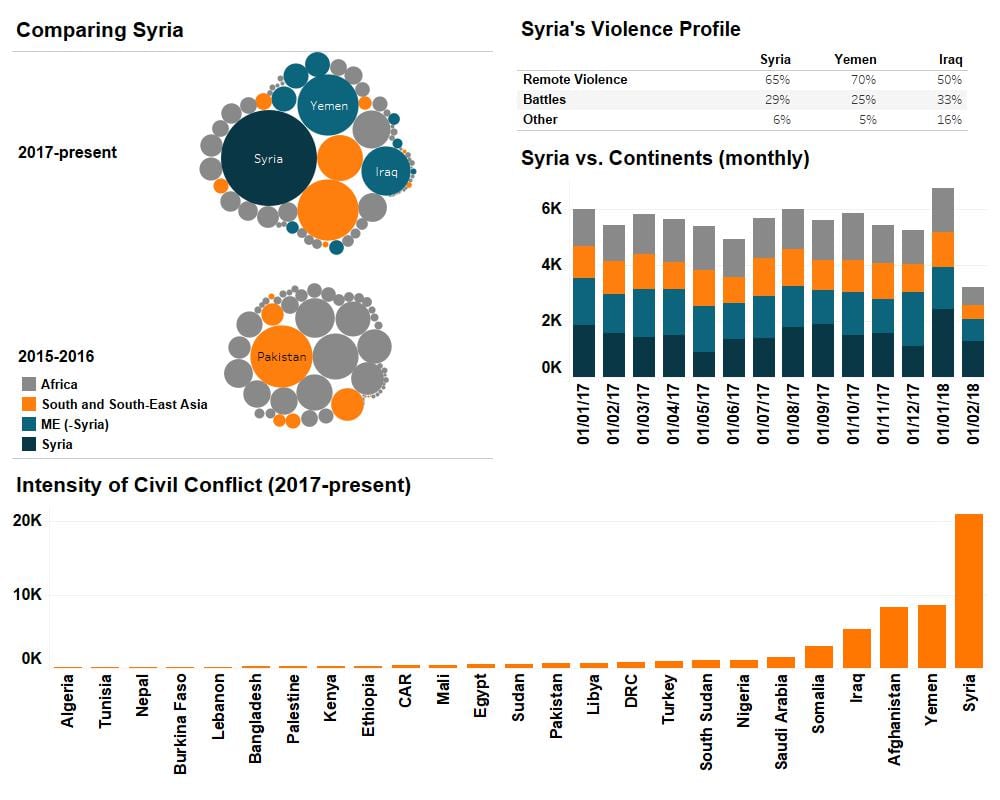

Syria is very bad compared to other spaces. Syria averages 70 violent reported events per day, and is currently as violent as all African conflicts plus South Asian fragile countries combined (see visual). To comprehend this number, take a combination of Kenya and Burundi’s lingering unrest, with the Congo’s emerging war, the continuing crises in CAR, Somalia, both Sudan’s, conflict in Nigeria, AQIMS increasing presence in West-Africa and Libya’s continuing problems, and still you do not equal the number of clashes and attacks in Syria’s conflict. Or consider that the number of events during one week of the Afrin offensive (the week of February 5, 2018) is similar in intensity to all violence in the Middle East (with active conflicts like Afghanistan, Yemen and Iraq) plus all protests/incidents in South-East Asia.

While scholars will contest over competing explanations for the decades to come, ACLED conflict data suggest two key insights. First, Syria is not special because its violence profile is very different. Syria shares a similar violence profile with Iraq and Yemen, meaning that actors engage in the same type of violence but just with an incredible intensity. Second, Syria is not more violent because it gets better reported on. Our ‘overlap-scores’ suggest that the detection rate of violence in Syria is not very different from other contexts. What may instead be a fruitful avenue is the finding that conflict size and intensity seem to be distributed according to an exponential function.[3] That means that the vast majority of conflicts experience (comparatively) little violence while some conflicts at the very tail end of the distribution are incredibly violent (see visual).[4] Syria unfortunately belongs to this latter category.

- “The War Over Syria’s War Dead,” Foreign Policy (blog), accessed March 1, 2018, https://foreignpolicy.com/2016/01/13/the-war-over-syrias-war-dead/.

- Author Alex Hopkins, “Airwars Annual Assessment 2017: Civilians Paid a High Price for Major Coalition Gains,” accessed March 1, 2018, https://airwars.org/news/airwars-annual-assessment-2017/.

- Lewis F. Richardson, “Variation of the Frequency of Fatal Quarrels With Magnitude,” Journal of the American Statistical Association 43, no. 244 (1948): 523–46, https://doi.org/10.2307/2280704.

- E.g. Thirty Years War (1618-1648), Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815) and both World Wars. See: Aaron Clauset, Maxwell Young, and Kristian Skrede Gleditsch, “On the Frequency of Severe Terrorist Events,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 51, no. 1 (February 1, 2007): 58–87, https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002706296157; Aaron Clauset, “Trends and Fluctuations in the Severity of Interstate Wars,” Science Advances 4, no. 2 (February 1, 2018): eaao3580, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aao3580; Lars-Erik Cederman, “Modeling the Size of Wars: From Billiard Balls to Sandpiles,” American Political Science Review 97, no. 1 (February 2003): 135–50, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055403000571.