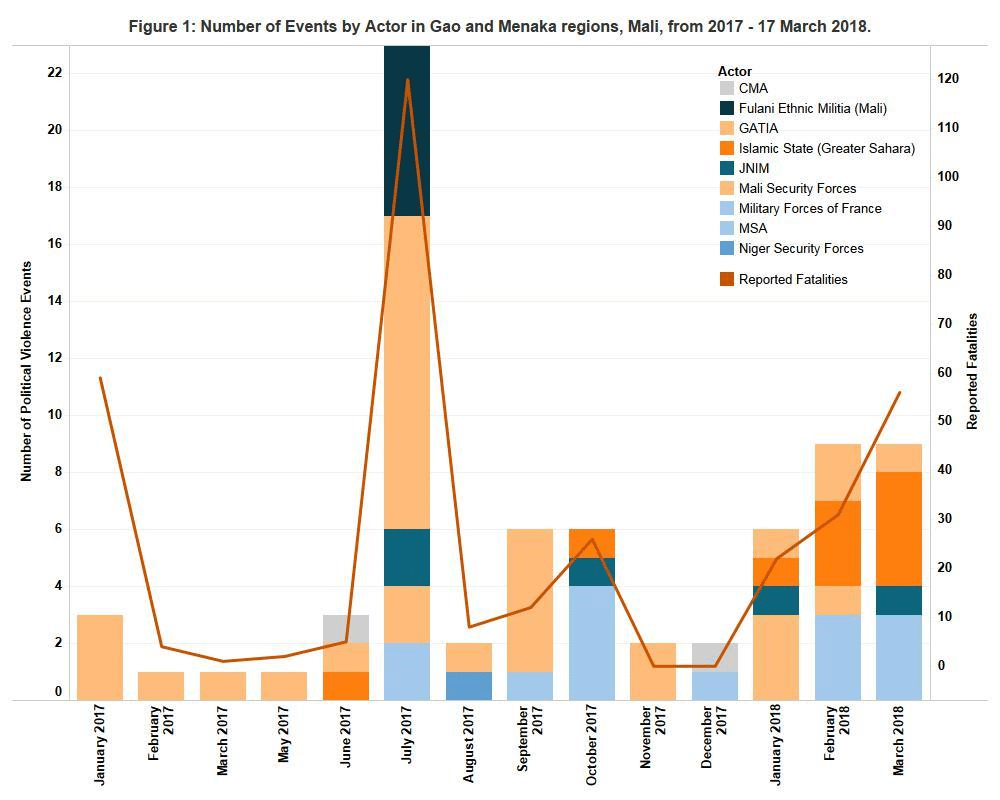

French forces of ‘Operation Barkhane’ aided by local militias step up operations against ‘Islamic State in the Greater Sahara.’ Since early February 2018, French forces of Operation Barkhane, aided by a coalition of local militias including the Movement for the Salvation of Azawad (MSA) and the Tuareg Imghad and Allies Self-defence Group (GATIA), have intensified operations targeting Islamist militants in the Gao and Menaka regions of north-eastern Mali (see Figure 1). The primary target has been the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS), led by Adnan Abu Walid al-Sahrawi.

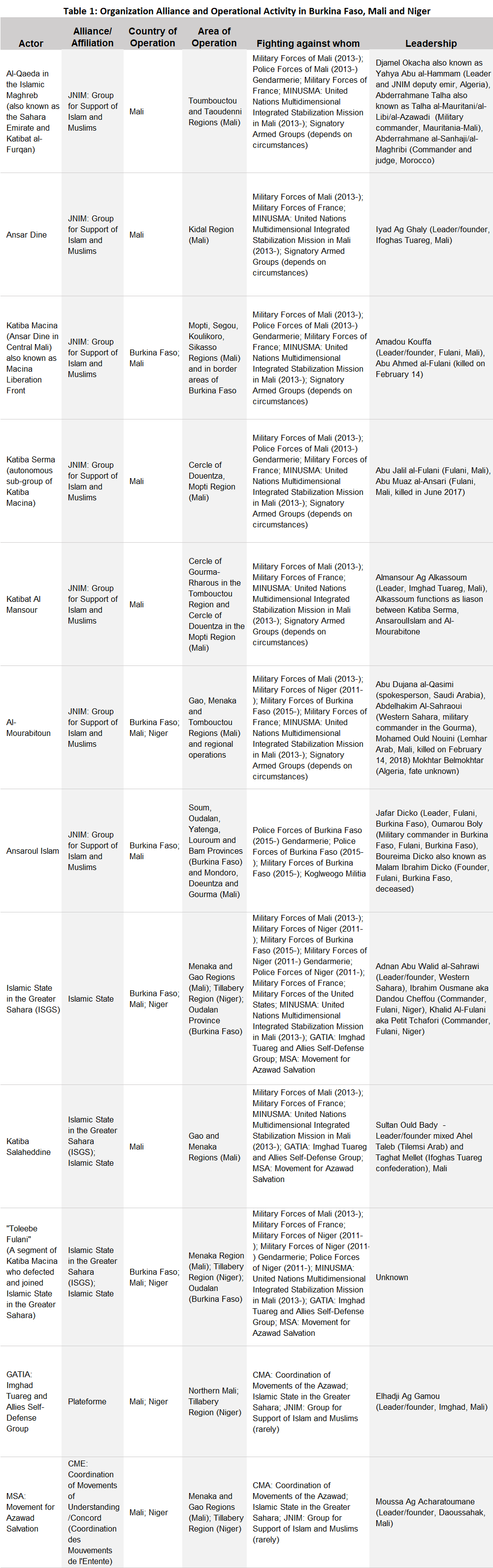

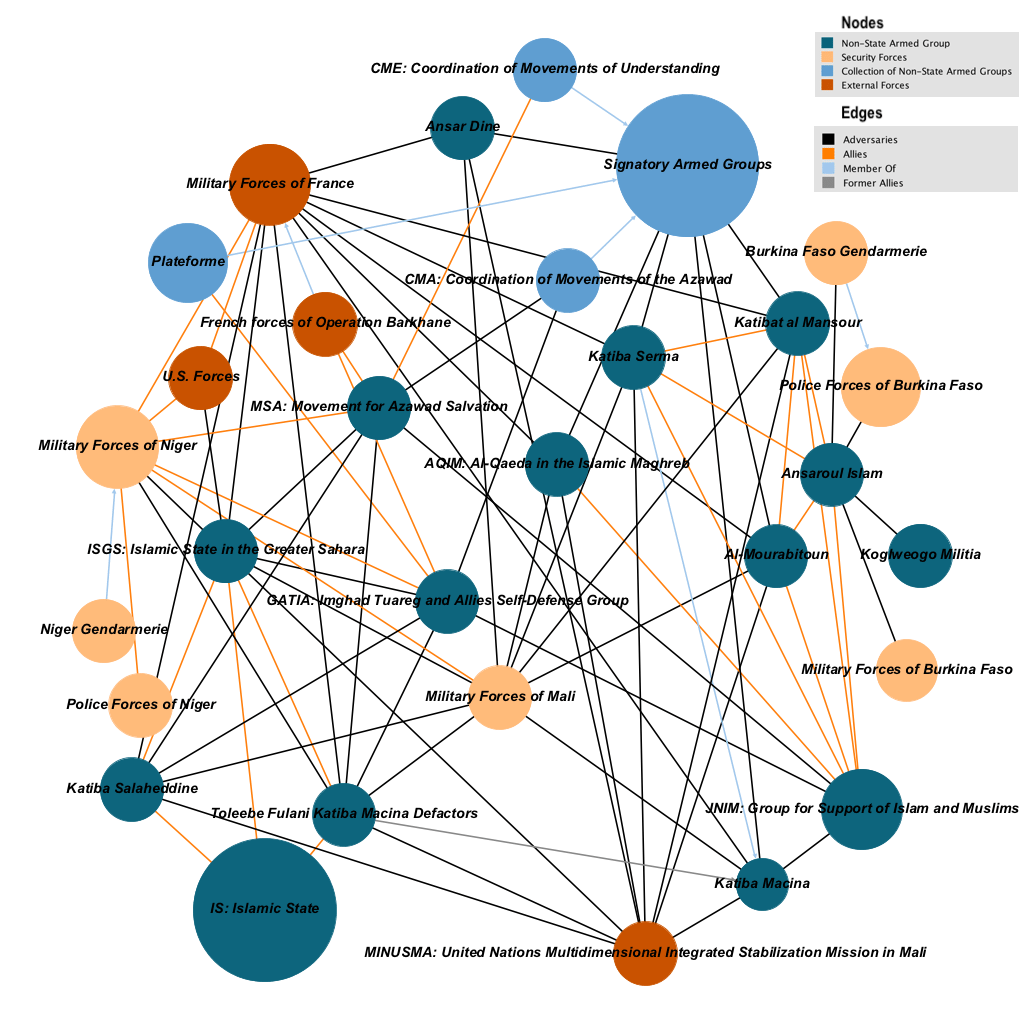

These operations have resulted in the killings and arrests of a significant number of militants, and seizures of arms, ammunition, vehicles, motorbikes, and other military equipment. Notwithstanding the successful results, the use of ethnic-based militias carries risks of exacerbating existing tensions between local communities; in particular between Fulani and Daoussahak pastoralists, communities who have been engaged in conflict that dates back to the droughts of the 1970s in the borderlands of Mali and Niger (Sandor, 2017). Fighting between these groups was very intense in the summer of 2017. While ISGS militants raided nomad camps and markets, Fulani notables argued that MSA and GATIA combatants killed Fulani herders as part of purported counter-militancy operations (Jezequel and Cherbib, 2017). The contention between Fulani and Daoussahak has likely enabled the growth of ISGS. The group also received reinforcements from a group of militants known as Katiba Salaheddine, led by Sultan Ould Bady who previously was loosely aligned with the Al-Qaeda affiliated Jama’ah Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM) (see Table 1 below). Another group of militants composed of Toleebe Fulani who previously were part of JNIM’s Katiba Macina also joined ISGS ranks. Both groups gave oaths of allegiance to Islamic State leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi (Menastream, 2018) (see Network Graph 1 below).

Network Graph 1

This network graph shows the complexity of the relationships between non-state armed groups in the Sahel, the shifting allegiances, and how these relationships are connected across sub-regional borders. It further shows how foreign forces, local forces and militias cooperate locally and across borders in various constellations to fight these militant groups. This graph displays over thirty groups (and constellations) of groups, each sharing various contradictory relationships with non-state organizations. Over the period of high activity in this region, more affiliations and alliances have emerged on the non-state side than the other types of organizations, with the important caveat that it does not display the component groups of signatory alliances.

There is a high probability that Islamist militants will continue to exploit grievances and vulnerabilities of increasingly disgruntled communities (Lebovich, 2018). This is likely to impact not only Fulani, but also various Tuareg sub-factions, Arabs and others. The Daoussahak people are at risk due to intra-group rivalries, and fragmentation caused by practices undertaken by MSA leader Moussa Ag Acharatoumane. This includes an alleged agreement with the Nigerien government in which he was reported to have vowed to fight militant groups in the Mali-Niger borderlands (Ag Ismaguel, 2018). That GATIA and MSA operate on the Nigerien side of the border and have a right to operate outside of their territory is an untold secret. Last weekend, GATIA combatants and Nigerien soldiers patrolling the area near the Mali border crossed paths about 50 kilometres from Mangaize. Due to confusion the two sides mistakenly exchanged gunfire and a Nigerien soldier was killed (ActuNiger, 2018).

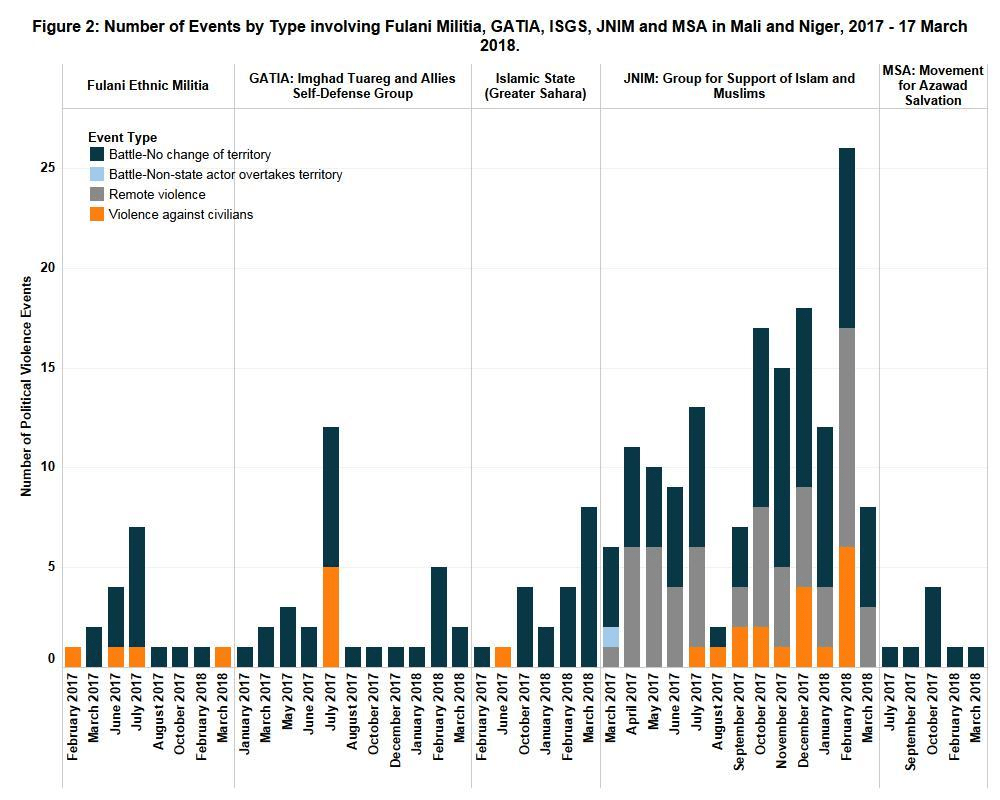

Although most of the attacks in the Tillabery Region of Niger have been attributed to ISGS (see Figure 2), only an attempted prison break in Koutoukale in October 2016 had been claimed until recently (Al-Akhbar, 2016). In mid-January, ISGS broke the silence and claimed a series of attacks communicated via the Mauritanian news agency ANI (ANI, 2018). Most noteworthy was the ambush against joint forces of U.S. Green Berets and Nigerien soldiers in Tongo Tongo in October last year, events that received significant global media coverage. ISGS also claimed a suicide car bombing against French forces which took place on January 11, 2018, between Menaka and In-Delimane (Le Monde, 2018). These attacks suggested that the group had obtained increased capabilities. Further, the group claimed responsibility for several attacks during 2017 in Niger, namely in the areas of Tilwa, Wanzarbe, Abala and Ayorou. Additionally, a deadly ambush in July last year against a Malian army convoy in In-Kadagotan, south of Menaka in Mali (RFI, 2017).

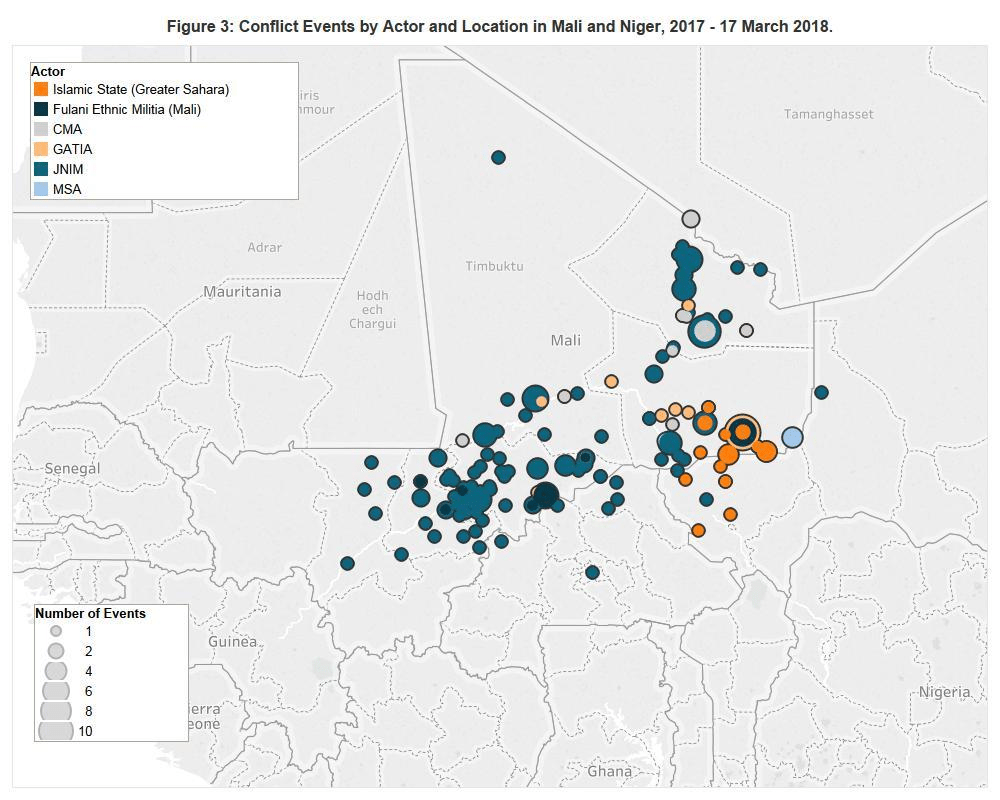

The hegemony of GATIA and MSA in the Menaka region, and attempts by these groups to exert influence over nearby areas, is highly contested. This is an issue that has stoked tensions and resulted in fighting with members of the Coordination of Azawad Movements (CMA). More recently in Talaytate, MSA claimed that one of its officers was assassinated (MSA, 2018), while CMA claimed its combatants repelled an attack on a checkpoint they were manning (CMA, 2018). CMA and GATIA are signatories of the 2015 Algeria-brokered peace accord, while MSA is not (International Peace Institute, 2017).

In early 2017, tensions mounted between the movements in Tidarmene, north of Menaka. In February, MSA and GATIA combatants raided the village, abused civilians, and seized vehicles and motorbikes on several occasions. The communities concerned subsequently engaged in a mock reconciliation process, wherein it was apparent that GATIA and MSA coerced members of the Ichadinharene tribe to acquiesce to their demands and withdraw their support from CMA. Three weeks after the purported reconciliation process a senior GATIA commander was assassinated in Menaka (Ag Ismaguel, 2017), the commander was accused of having led the aforementioned raids on the village of Tidarmene. Those suspected of having carried out the assassination were associated with CMA and are believed to have been tortured while detained and executed by GATIA. Later in October, a senior MSA commander was killed in an attack on a camp about 30km from Menaka, presumably by ISGS militants (RFI, 2017).

MSA is currently a counter-militancy partner favoured by French forces of Operation Barkhane. The first publicized joint effort took place on June 1, 2017, in the wake of the Abala attack carried out by ISGS. The Nigerien and the Malian armies, France’s Operation Barkhane, GATIA and MSA coordinated efforts and killed the majority of the attackers who were returning towards their camp (Armée Française, 2017). This joint operation was preceded by a working visit to Paris where MSA leader Ag Acharatoumane and GATIA leader El Hadj Ag Gamou met with French security and military officials (Jeune Afrique, 2017). As late as March 11-12 on the Malian side of the border, joint forces recovered a vehicle and arms seized by ISGS militants from U.S. special forces killed in Tongo Tongo, Niger, in October last year (Menastream, 2018).

Evidently, the use of local militias can provide international forces with important assets in terms of intelligence gathering and tracking, but it also risks exacerbating existing tensions and placing civilians at risk. There is an imminent threat that civilians on both sides could get caught in the crossfire, taken prisoner, or abducted solely based on ethnic affiliation or kinship. Islamist militants have a record of retaliating against locals collaborating with international forces and may carry out revenge attacks against communities considered close to the militias involved in counter-militancy operations. There are reports that the MSA, under the pretext of “fighting terrorism”, has attempted to eliminate local opposition, and indiscriminately killed Fulani herders.

Overall, MSA and GATIA’s hegemony in the Menaka Region remains contested (see Figure 3). The conflict playing out in the Mali-Niger borderland resembles other hyper-localized conflicts in the sub-region. Contention is largely based on the sharing of resources, and a political setting lacking inclusiveness, but competition is playing out along ethnic lines.