Demonstrations make up 90% of all events in India, yet the modes in which they manifest, who is involved in them, and whether state forces get involved vary based on the region of India in which they occur.

In addition to demonstrations like those seen across other country contexts, there are some distinct types of demonstrations that are also often seen across India:

- Dharna: A mode of compelling payment or compliance, by sitting at the debtor’s or offender’s door until there is compliance with the demand. For example, on March 19, in Coimbatore city, the joint action council (JAC) of government doctors associations staged a dharna reiterating demands, such as wanting a 50% quota for state government doctors for postgraduate medical seats (PG-NEET) and payment on par with central government doctors. About 7% of demonstrations in India since 2016 fall under this classification.

- Gherao: A protest in which workers prevent employers or managers from leaving a place of work until certain demands are met. For example, on March 5, in Panipat city, Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) councillors gheraoed the Municipal Commissioner at his office to protest the non-lifting of garbage. About 1% of demonstrations in India since 2016 fall under this classification.

- Roko: A protest or demonstration typically involving the obstruction of a railway or road. For example, on April 3, in Salem city, opposition parties led by Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) staged a demonstration and road roko agitation in front of the office of the Principal General Manager of Bharat Sanchar Nigam Limited (BSNL) demanding the constitution of the Cauvery Management Board. About 10% of demonstrations in India since 2016 fall under this classification.

- Jail Bharo: A method of protesting for a cause, where protesters voluntarily let themselves get arrested in order to fill the jails. For example, on January 12, in Karnataka, BJP staged a jail bharo agitation in various district headquarters, protesting against Chief Minister Siddaramaiah for allegedly branding BJP, Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), and Bajrang Dal as terrorist organizations. Less than 1% of demonstrations in India since 2016 fall under this classification.

- Bandh: A general strike across the state or country called for by political activists, where the activists expect the general public to stay at home and to not report for work. For example, on April 2, in Hyderabad, Dalit groups joined a nationwide Bharat Bandh call given by the Dalit caste group against the Supreme Court order, holding rallies that brought traffic to a halt in many areas of the city. About 2% of demonstrations in India since 2016 fall under this classification.

- Hartal: A closure of shops and offices as a protest or a mark of sorrow. These are seen elsewhere in South Asia as well. For example, on October 13, in Jammu, casual workers of the Power Development Department who have been on Kaam Chhoro Hartal for 23 days in support of their demands, raising slogans to urge the government to regularize the policy for all casual workers who have completed five years of service. Less than 1% of demonstrations in India since 2016 fall under this classification.

- Hunger Strike: A prolonged refusal to eat, carried out as a protest by a congregation of demonstrators. For example, on April 3, in Coimbatore city, over 5,000 cadres of All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK) gathered to conduct a one-day hunger strike at Gandhipuram to condemn the Union government for failing to constitute the Cauvery Management Board (CMB). About 2% of demonstrations in India since 2016 fall under this classification.

Demonstrations are met with various types of opposition from state forces, including the building of barricades to contain protesters, arrests, and the use of force through lathi charge, water cannons, pellet guns, and, in rare occasions, live ammunition. Lathi refers to a long, heavy, iron-bound bamboo stick used as a weapon, especially by police. Usually, “lathi” is used as a modifier, such as in “lathi charge.” Police and other state security forces use lathi charges to physically engage protestors or rioters who are becoming unruly, violent, or obstinate in response to demands. This tactic is seen elsewhere in South Asia as well.

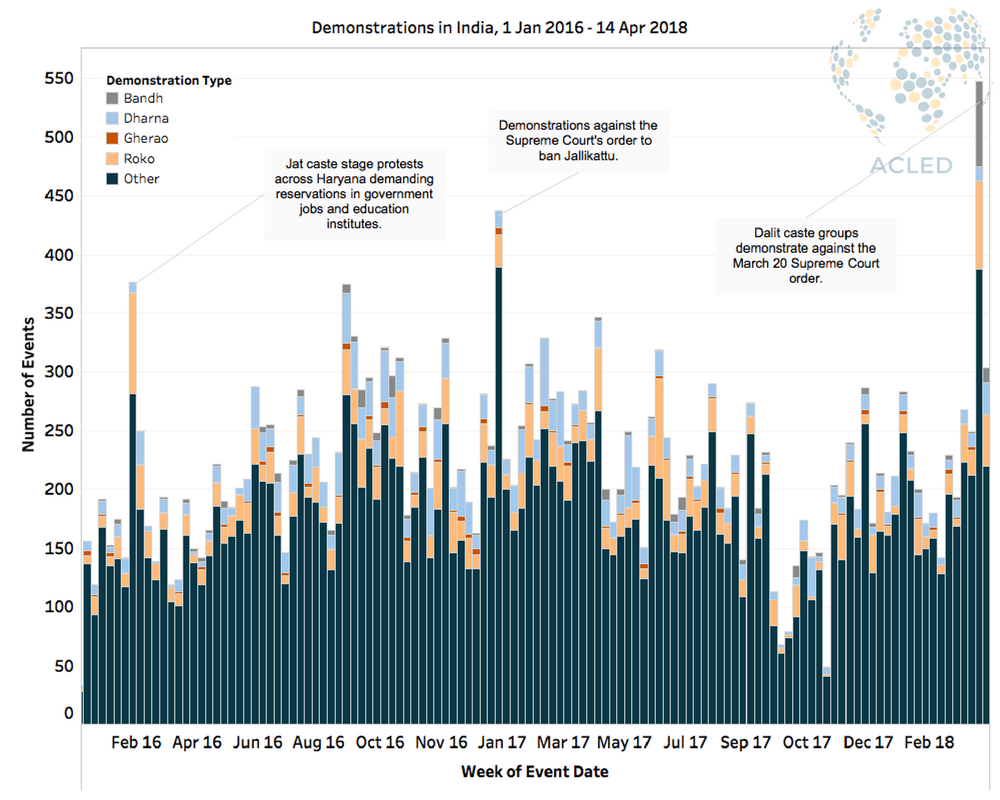

Three periods since 2016 have resulted in a spike in the number of demonstrations (see graph below). In February 2016, members of the Jat caste staged protests across the North Indian state of Haryana, demanding reservations in government jobs and education institutes under the OBC category. In January 2017, there were demonstrations against the Supreme Court’s order to ban Jallikattu, a Tamil bull taming sport. Most recently, in April 2018, Dalit caste groups demonstrated against the March 20 Supreme Court order, which they contended had diluted provisions of The Scheduled Castes & Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act of 1989.

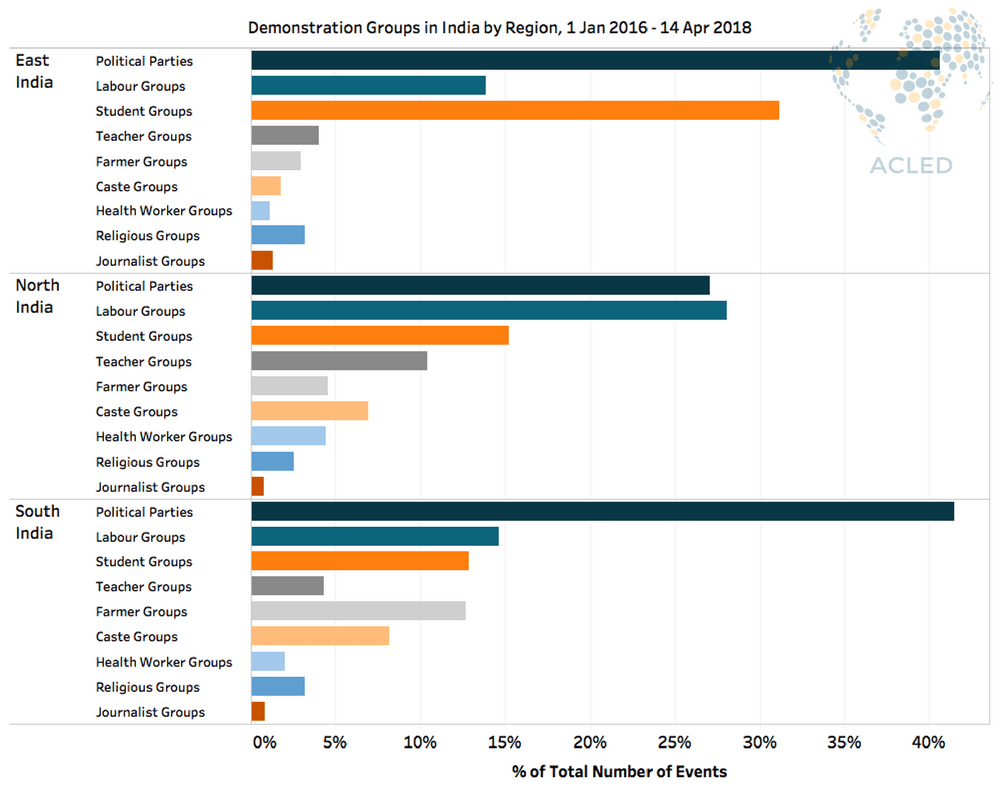

Since 2016, the highest number of demonstrations – over 50% – occur in North India, one-third occur in South India, and the remainder in East India.[1] In analyzing the demonstrations by the type of group demonstrating, there are nine groups that have the most involvement: political parties, labour groups, students, teachers, farmers, different caste groups, health workers, religious groups, and journalists (see graph below).

In South and East India, most demonstrations are organised and led by political parties. Supporters of Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and Indian National Congress (INC) are the most active participants in these demonstrations. In North India, however, labour groups represent a slight majority of group demonstration events in the region. Student groups too are very active across all of the regions.

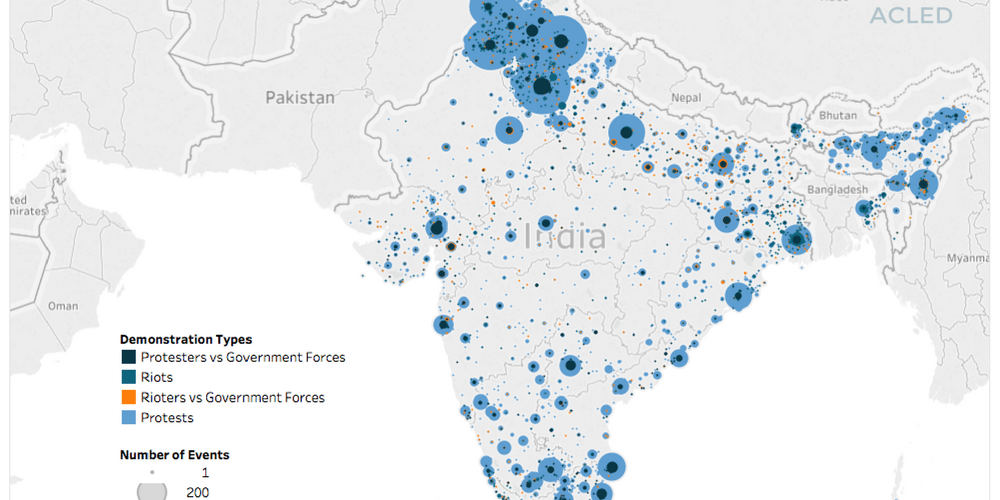

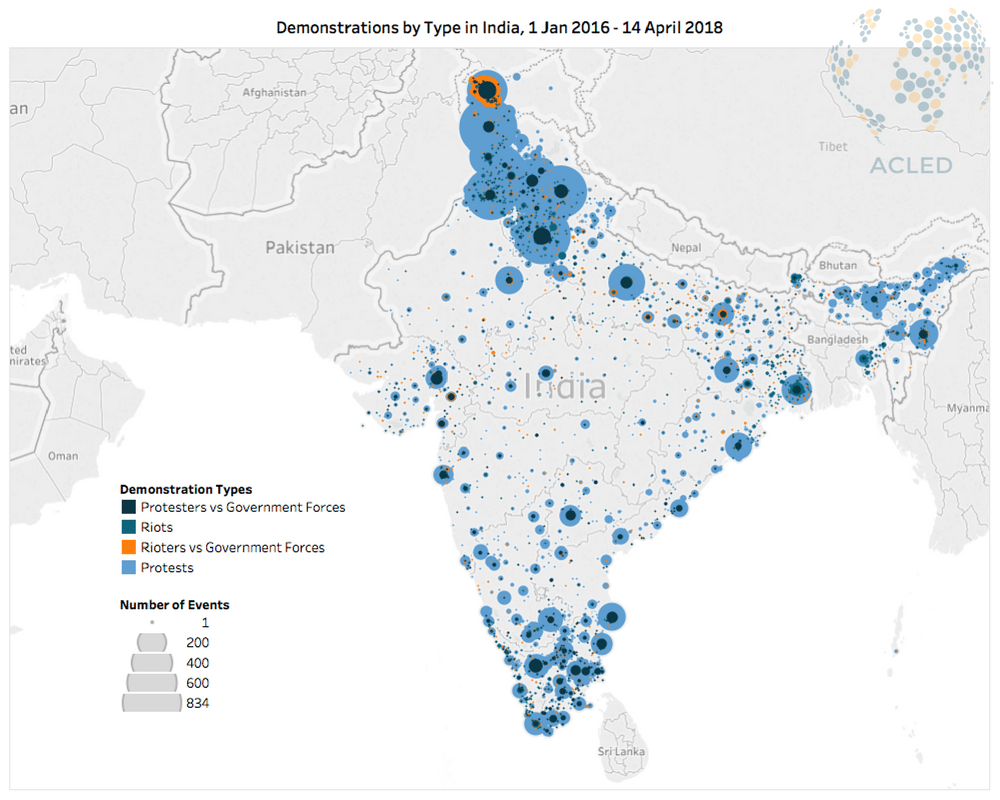

The majority of demonstrations in India are peaceful and can be seen across the country, though are especially prevalent in proximity to metropolitan areas, especially in Punjab and Uttarakhand (see map below). While peaceful protests account for nearly three-quarters of demonstrations across India, the ratio of violent to nonviolent demonstrations is greatest in North India compared to South and East India. The number of violent demonstration events involving government forces only account for around 9% of all demonstrations.

Apart from a few months of heightened tension during the last two years, the majority of the demonstrations in India each month are peaceful, with only about 1 in 5 resulting in violence. Citing geographical differences as well as differences in the types of groups that are demonstrating, there appears to be a greater ratio of violent to nonviolent demonstrations in North India than in South and East India. Whether state forces get involved in the demonstrations varies on a number of factors, including the scale of the protest and the effect on public services and general law and order.

[1] (North India refers to Jammu & Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh, Punjab, Uttarakhand, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh; South India refers to Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Puducherry, Lakshadweep, Andaman and Nicobar, Daman and Diu, Dadra and Nagar Haveli, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Odisha, Maharashtra, Gujarat, Goa, Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan; East India refers to Bihar, Jharkhand, West Bengal, Tripura, Sikkim, Meghalaya, Assam, Mizoram, Manipur, Nagaland, Arunachal Pradesh )