Ahrar al Sham (AAS) has been a major player in the Syrian conflict since the group was formed in December 2011. Bringing together a number of Syrian Islamist groups to fight under a single structure, AAS’ primary stated objective was to bring an end to the Assad regime and see the establishment of a Sunni Islamist state in Syria (Stanford, 2017).[1] After the de-facto unravelling of the Free Syrian Army in 2013, AAS became one of the largest and most effective rebel groups fighting regime forces with around 20,000 fighters (The Economist, 2013).

Despite some significant setbacks to the group (Abadzeid, 2018), many still look to AAS as a key component in the continued rebel fight against the regime. However, analysis of ACLED data reveals that, across 2017 and 2018, AAS has been more preoccupied with rebel infighting than with combating the regime (see chart below), contradicting popular beliefs about what rebel groups in general— and AAS in particular —are doing in Syria.

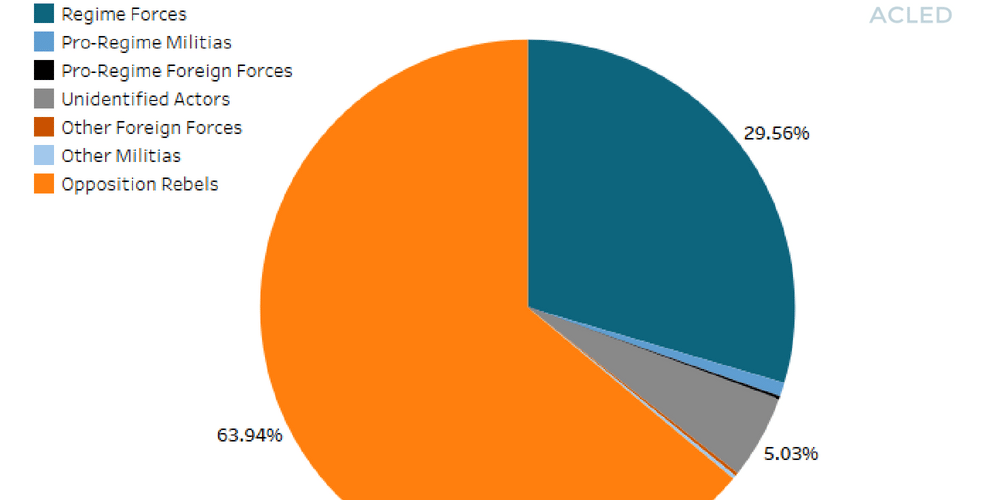

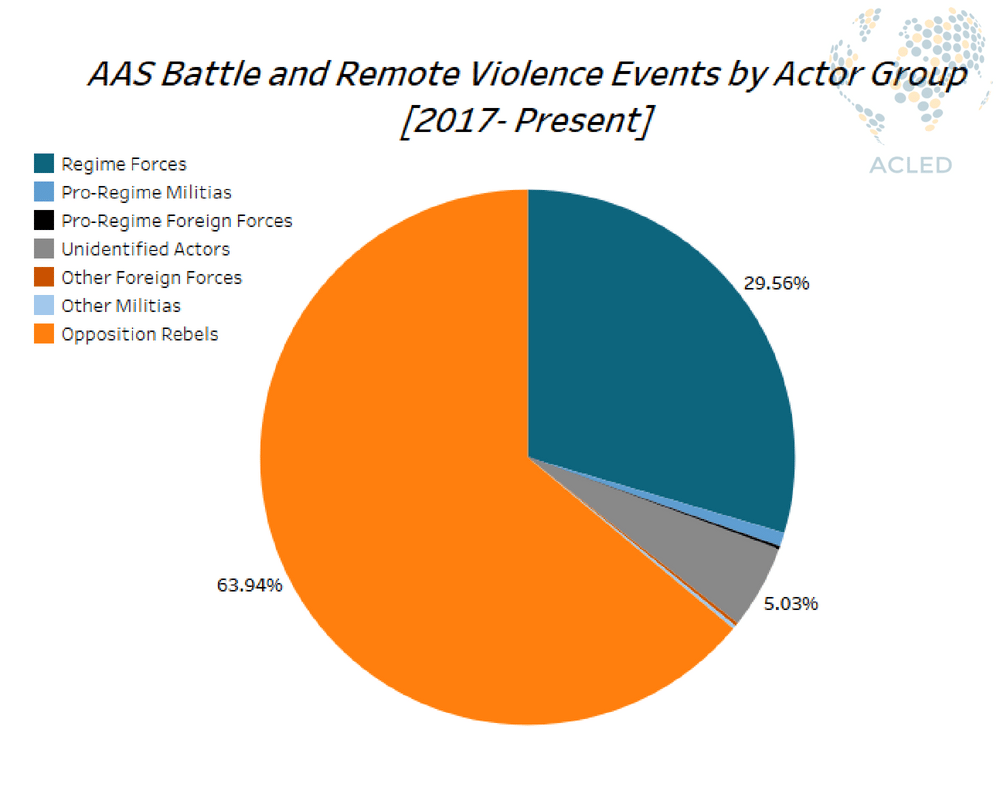

Examination of remote violence and battle events involving AAS from January 2017 to the present reveals that AAS has been overwhelmingly engaged in violence with other rebels, comprising 63.94% of their overall reported activity, and only engaging with regime and pro-regime forces approximately 31% of the time.

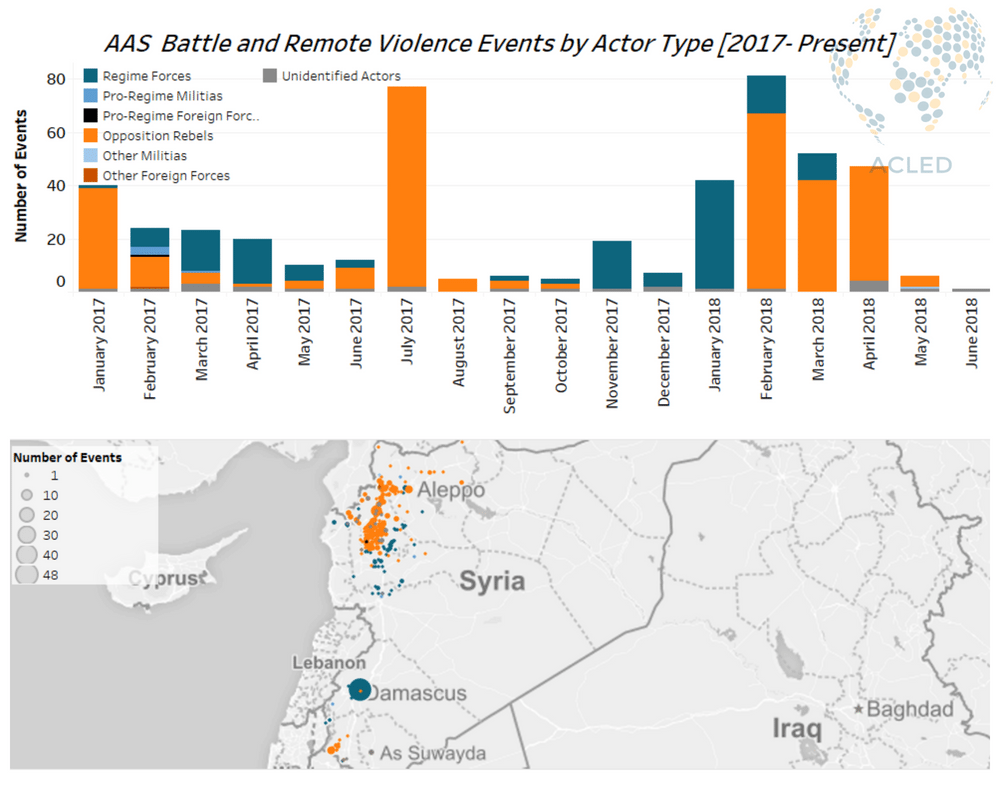

Further analysis demonstrates the temporal and spatial patterns of AAS’ limited engagement with the regime, where AAS engaged with the regime in the spring of 2017 and between November 2017 and January 2018 during regime offensives on the frontlines of AAS territories, primarily in the Eastern Ghouta in Rural Damascus and around key frontlines in Hama and Idleb (see below). This suggests that AAS has been engaging in a mostly defensive manner with regime forces and in contexts where its frontline positions are directly challenged by regime advancement.

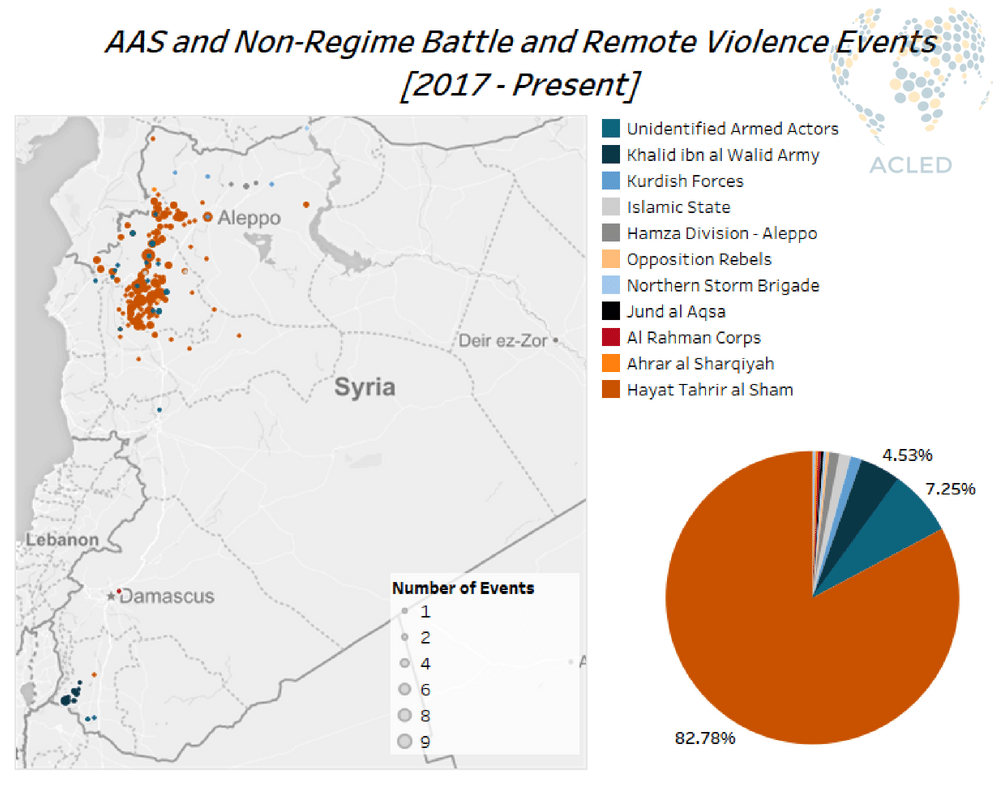

Excluding events in which AAS engaged with regime and allied forces (see below), it’s main adversary across 2017 and 2018 has been Hayat Tahrir al Sham (HTS), where 80 percent of the non-regime events are interactions between the former allies as their increasing rivalry for dominance in Idleb came to a head in early 2017 and continued in 2018 (Grinstead, 2018). The group’s second most common rival is the Islamic State-affiliate, Khalid ibn al Walid Army, with 4.53%. In addition to fighting HTS, it is no surprise that AAS is engaging with this group as it is attempting – with Turkey’s help – to show itself as a worthy ally and a viable replacement to both the Assad regime and IS (Mroue, 2015).

Overall, AAS appears to be more interested in keeping its ever-shrinking territory and implementing its vision of governance rather than facing the inevitable danger of Assad regime’s forces. While HTS poses a more direct existential threat to AAS in its Idleb stronghold, AAS non-engagement with the regime may reflect a prioritization of resources towards governance in an effort to gain legitimacy, whether in the eyes of Syrian civilians or in those of in the international community.

With the regime’s looming offensive to retake Idleb – the last rebel held province – (Taskomor, 2018), it will be interesting to see how this scenery changes when AAS can no longer avoid direct confrontation with the regime. Will it play out in the same way as the battle of Eastern Ghouta did earlier this year – forcing rebel groups to put aside rivalries and focus on holding off the regime?

[1] Unlike the more globally-ambitious groups such as the Islamic State (IS) and Hayat Tahrir al Sham (HTS), Ahrar al Sham limits its quest for the creation of an Islamist state to Syrian territory. While the group’s past ties to Al-Qaeda raises questions about how “moderate” it can be considered, in comparison to IS and HTS, it has attempted to rebrand itself as a more liberal Islamist alternative for Syria’s post-Assad future (Standford, 2017).

AnalysisCivilians At RiskConflict MonitoringFocus On MilitiasGovernanceIslamic StateIslamist ViolenceMiddle EastPolitical StabilityPro-Government MilitiasUnidentified Armed GroupsVigilante Militias