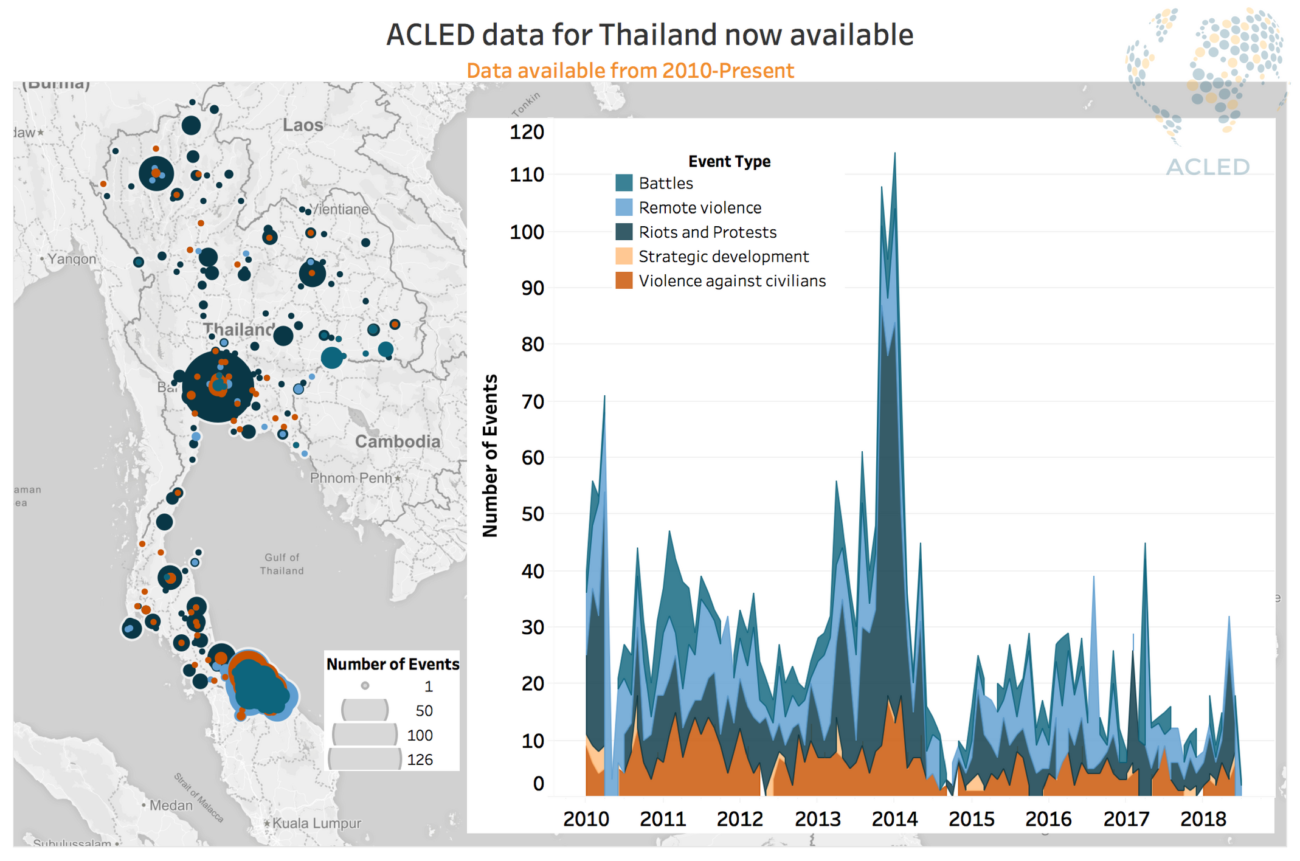

ACLED’s Thailand dataset contains nearly 3,000 recorded political violence, protest, and other non-violent political events from 2010 through the present. Throughout most of the country, the most common events are riots and protests. In general, the political landscape in Thailand since 2010 can be broken cleanly into two periods: before and after the 2013-2014 crisis, which ended in the removal of the incumbent prime minister. Prior to anti-government demonstrations erupting in October 2013, there was an average of 30 events reported per month in the country, including violence against civilians, remote violence, and riots and protests. The peak in 2013-2014, almost entirely due to a spike in the number of riots and protests, represents the height of the Thai political crisis, in which demonstrations erupted across the country with the aim of halting the continuing influence of Thailand’s former prime minister, Thaksin Shinawatra, who was seen as a corrupting influence on Thailand’s democracy. Protests originally ensued after Thailand’s House of Representatives passed a bill proposing amnesty to Shinawatra and other former and deposed politicians. Following months of unrest, the Royal Thai military staged a coup d’etat in May 2014, resulting in the army chief general taking power in August of the same year. The establishment of the military junta was followed by an immediate decline in the number of political violence, protest, and other non-violent events that were recorded in Thailand, likely a result of the increased suppression by the newly instated military state.

In Thailand’s southern provinces, however, battles, remote violence, and violence against civilians occur more frequently than riots and protests. An ongoing separatist insurgency in these majority-Muslim provinces has fomented violence for decades. The grievances of the majority Malay Muslim population in these provinces are rooted in religious, racial, and linguistic differences from Thailand’s Buddhist majority, and the militants operating in these provinces rely heavily on remote violence tactics, including the frequent targeting of military patrols with improvised explosive devices (IEDs). The insurgents also target infrastructure – such as electrical grids – and are involved in widespread incidents of violence against civilians, often in the form of targeted attacks on individuals.

AnalysisAsiaCivilians At RiskConflict MonitoringPressRemote ViolenceRioting And ProtestsViolence Against Civilians