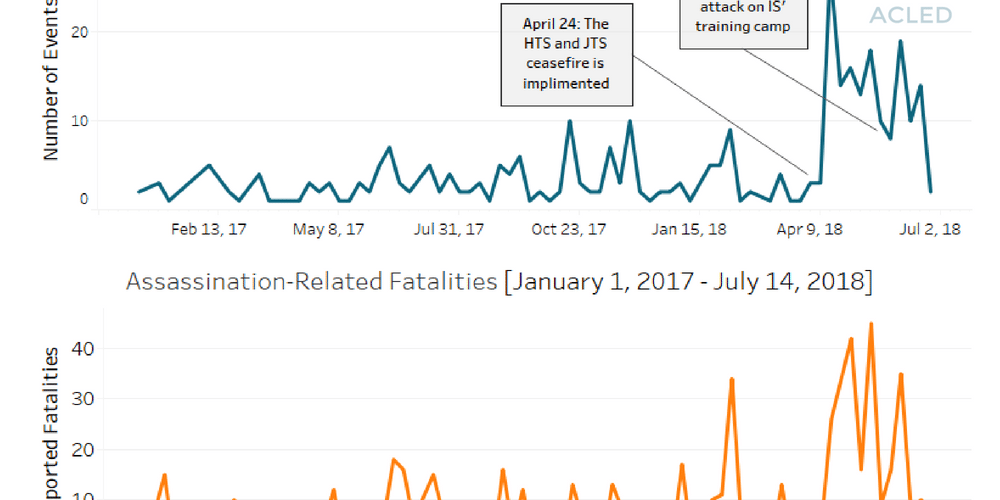

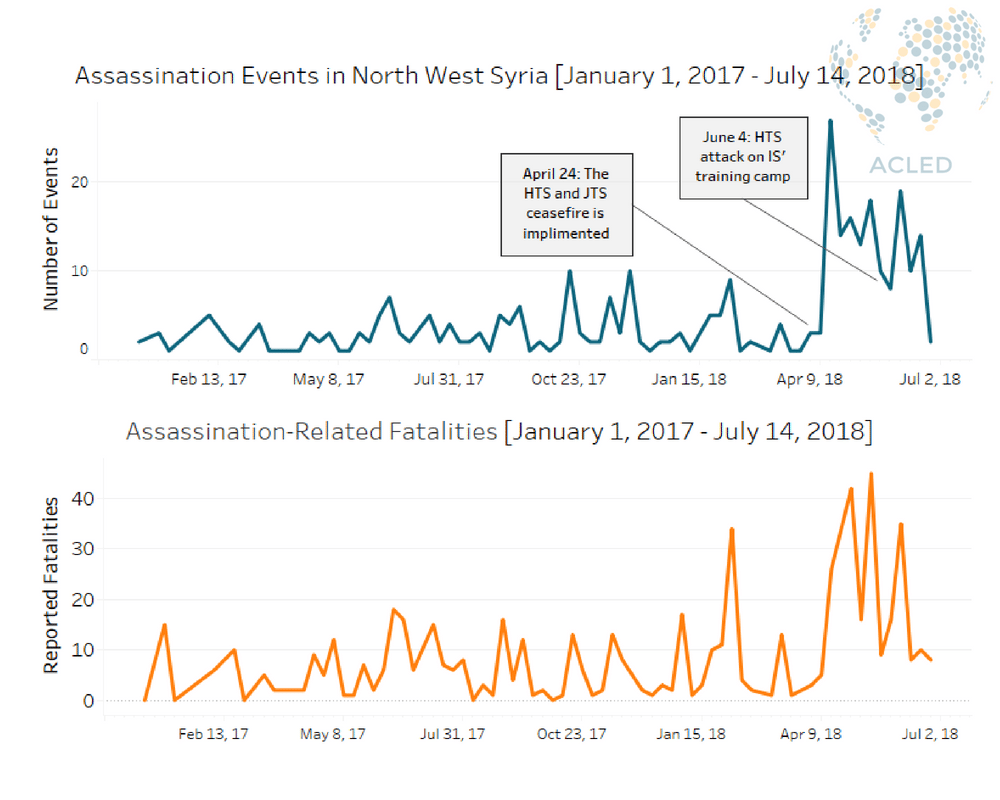

Syria’s North West[1] rebel stronghold has recently witnessed a wave of targeted assassinations against rebel factions and, specifically, against Hayat Tahrir al Sham[2] (HTS) members and leadership. While ACLED data show that assassinations in this area took place at lower levels across 2017, the recent wave of assassinations shows higher frequency and lethality[3] than earlier months (see graphs below).

Rival Rebel Groups

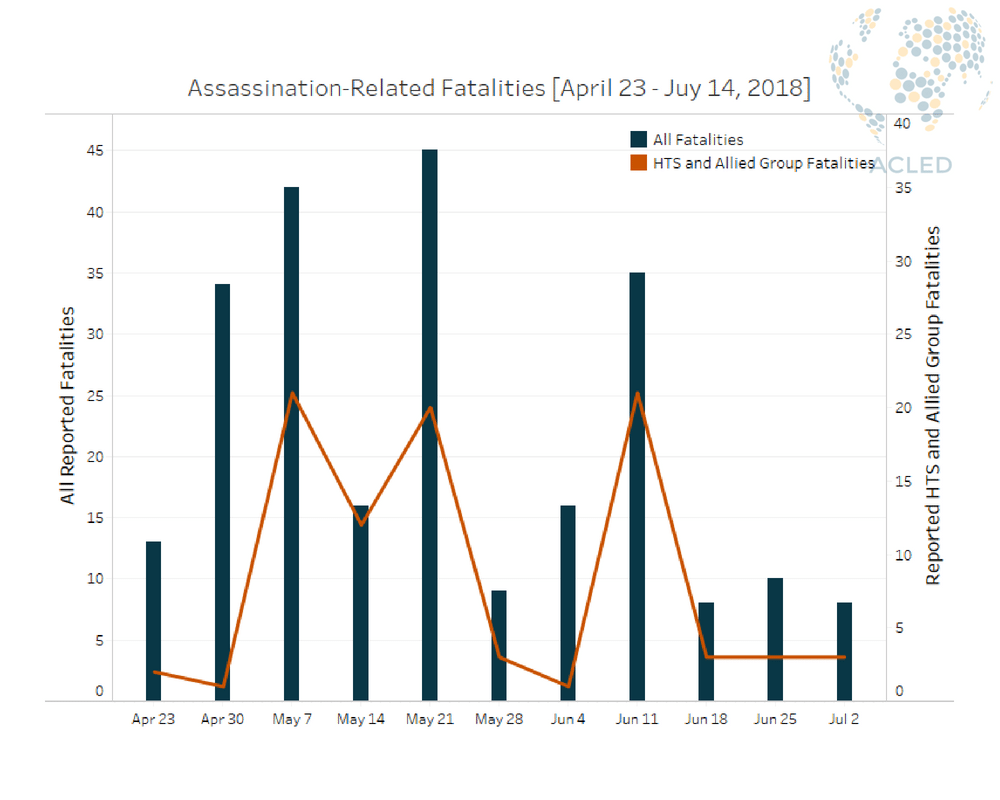

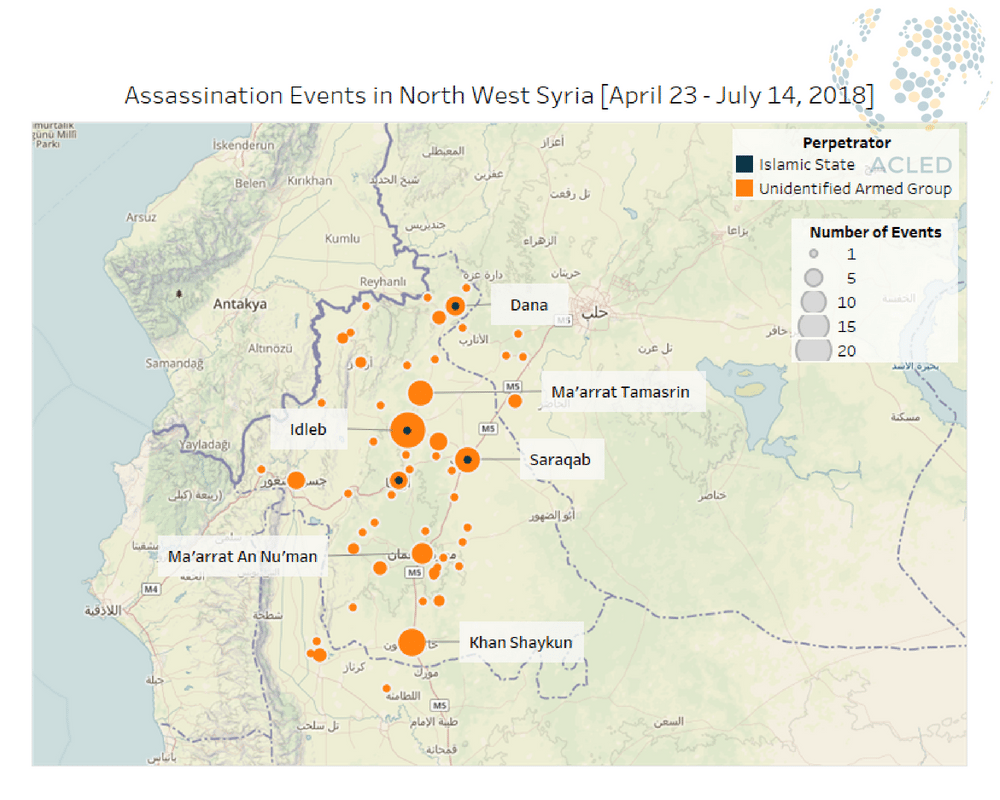

ACLED data show that assassination operations in the area sharply increased in late April, coinciding with the implementation of a ceasefire agreement between HTS and JTS on April 24th following a two-month period of infighting termed the “Abolition War” (see graph above)[4] Following the implementation of the ceasefire, direct confrontation[5] between the two sides significantly decreased. However, the first major spike in assassinations, a more covert means of confrontation, took place in the week following the agreement in the form of IED attacks and small arms fire targeting members and leaders of both sides.[6] While such assassination operations targeted members of both parties, the majority of attacks have been against high-profile members and foreign fighters of HTS, as well as against members of other Islamist groups who supported HTS in the Abolition War (see graph below). The focused targeting of HTS indicates that rival rebels have likely utilized assassinations to weaken HTS leadership.

The Regime

The weakening of HTS leadership is also a goal of the regime, which sees HTS dominance, and rebel control in general, in the North West as a threat to its immediate and long-term power. In fact, several media sources have claimed that regime and allied forces have placed covert operatives, or “sleeper cells,” in rebel-held areas to carry out operations to target rebel leadership (Al Masdar, 2018). In carrying out assassinations against HTS and other rebel groups, these attacks would not only weaken the organizational structure of prominent groups but also work to ensure that the rebel-held areas, particularly in Idleb, remain insecure for both rebels and civilians alike. Such insecurity would pave the way for the possibility of a future regime offensive to retake the area and may pressure civilians to accept the relative stability of regime control.

The Islamic State

Lastly, IS is widely believed to be the main perpetrator of these assassinations (Nedaa Syria, 2018) and is the only group specified as having carried them out in ACLED data (see map below). IS has likely also carried out a number of unattributed attacks against HTS, its primary Islamist rival in Syria, through sleeper cells in Idleb or through former members of its affiliate, Jund Al Aqsa, who chose to stay in Idleb rather than join IS in Ar-Raqqa after the rebel faction’s (including HTS) campaign against them in early 2017. In fact, data show that assassination operations spiked for a second time (see chart above) after HTS’ attack on a covert IS training camp in rural Idleb on June 4th, 2018, which killed 22 suspected IS fighters.[7] IS responded to the initial attack by publishing a video of the execution of three HTS fighters in Idleb on June 10th, in addition to carrying out several other assassinations against HTS members in different areas of NW Syria.

These assassinations, likely carried out by three distinct groups with motive to act against HTS, have created a deteriorating security situation in which no rebel actor holds sufficient power to impose stability. These attacks have not only increased insecurity for the rebel groups, impeding their ability to maintain control and govern civilians, but have affected civilians themselves with nearly 50 civilians killed in the cross-fire of these attacks (SOHR,2018). Such insecurity is likely to breed further attacks as Idleb becomes the last major provincial enclave of rebel control in the country, raising questions not only about the future of rebel infighting and control in the area, but of the ability of HTS and other groups to withstand a possible future regime offensive.

[1] The area concerned includes Idleb province, northwestern Aleppo, and northern Hama.

[2] The former Al-Qaeda affiliate known previously as Jabhat Fateh al Sham and Al Nusra Front.

[3] Lower estimates report 238 assassination-related fatalities in the area between April 26th to July 17th, 2018 (SOHR, 2018) while ACLED data suggesting as many as 600.

[4] On February 20th, 2018, wide-scale fighting, dubbed the “Abolition War” broke out between HTS and JTS in north west Syria following the assassination of HTS commander Abu Ayman al-Masri on February 16th, an act for which Nour al-Din al-Zenki Movement (a member of JTS) was accused. See (Grinstead, 2018) for previous ACLED analysis on the Abolition War.

[5] In the form of remote violence, such as shelling, and battles.

[6] Some of these assassination operations were likely retaliatory attacks for assassinations that took place during and even prior to the “Abolition War.”

[7] Moreover, HTS launched another operation against IS sleeper cells in Sarmin town in the same countryside on 28th of June, resulting in fierce clashes between HTS and IS fighters in the town (Enab Baladi, 2018).