In today’s world, external actors are more often intervening in conflicts globally; more domestic armed conflicts have involved external states’ direct intervention in recent years than in any year since the end of World War II. This is especially the case in the Middle East, in which this internationalization is how foreign military power is being projected in the region. This has occurred at the same time that peace operations have flourished in the past 20 years; and while rising economic powers such as Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa (BRICS countries) have participated in recent missions worldwide. Indeed, tensions with Russia have been one of the primary reasons for international parties to work outside of existing frameworks like NATO and the United Nations Peacekeeping Operations. While foreign military involvement in African and Asian conflicts continues to take the form of multilateral peacekeeping or enforcement missions (for example, see this recent ACLED piece on UN missions in Africa), military involvement in the Middle East has increasingly been through coalitions between a number of countries, and outside of multilateral organizations.

The advantage of coalitions is manifold: coalitions can be geopolitical, and their loosely-organized nature allows for temporary and isolated cooperation in the context of mutual interests. This, at times, brings together states that are otherwise not always friendly toward one another (e.g. Qatar, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates [UAE], and Egypt are all part of the Global Coalition Against Daesh despite their own tensions). Coalitions operating with a clearly defined yet limited goal, and a relatively open-access mechanism for members to opt in or out of particular operations, also gives coalition members an advantageous flexibility. They can also serve as a shield against the impression of explicit direct involvement in military operations abroad, especially in a contentious region — something Western states often grapple with while trying to manage repercussions from their constituencies at home. States can both use the coalition as a facade to wash their hands of perceived unilateral involvement overseas, or can benefit from the anonymity that the coalition front can offer, hence minimizing their perceived involvement in overseas engagement altogether as well as in specific military operations. Given that violence in the Middle East is believed to have risen since the beginning of the 2000s in tandem with the presence of jihadi groups (with linkages to Europe), and that the US appears to be taking a more pragmatic course to deal with the increasing geo-political instability, coalitions in the region are likely to continue.

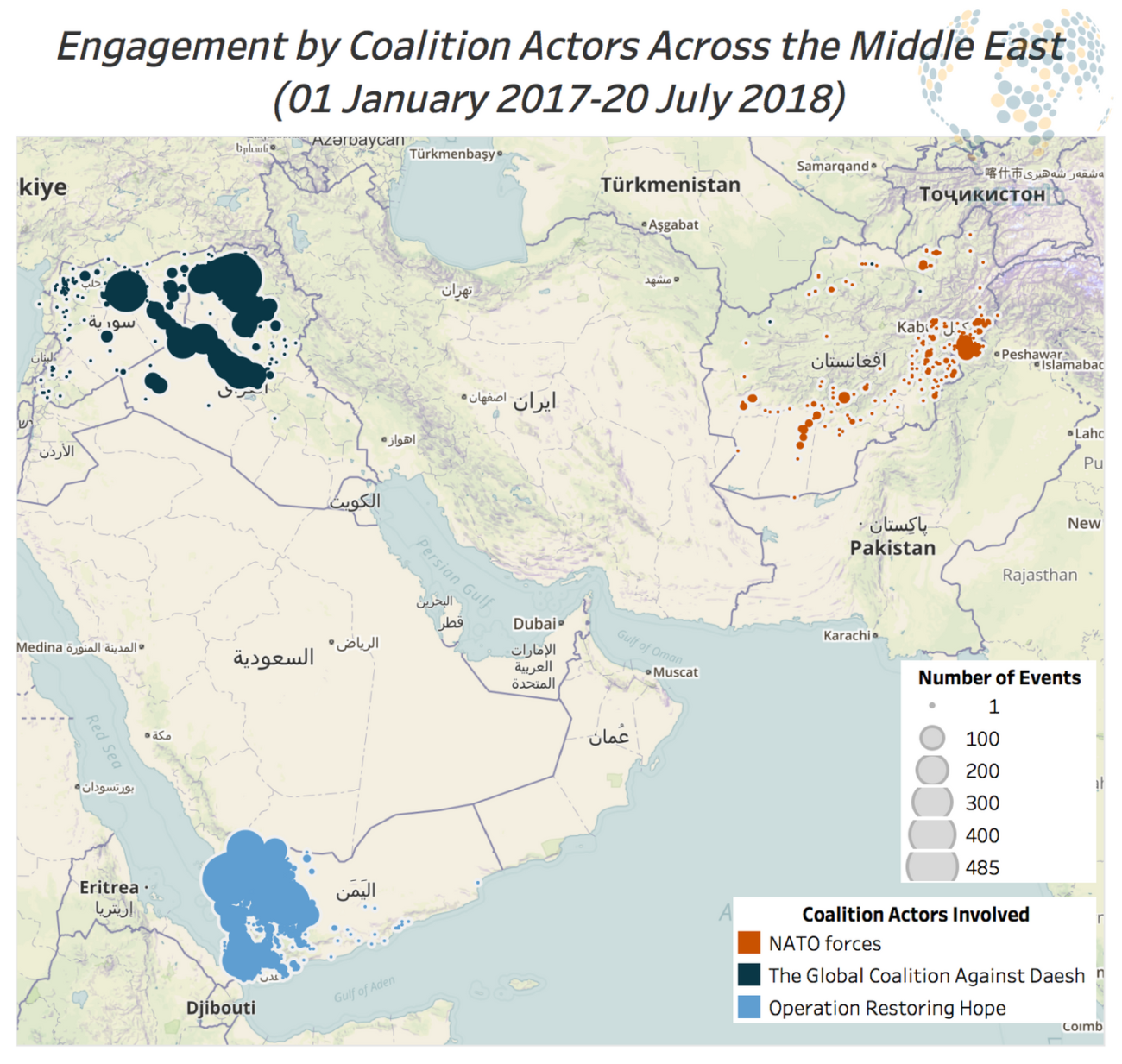

Coalitions are diverse actors. Their level and modes of engagement in conflicts vary depending on both their diverse goals, their composition, and the conflict they are combatting. For example, in Yemen, Operation Restoring Hope is quite an active actor – in fact, it has been the single most active conflict actor in Yemen since January 2016; in Iraq, the Global Coalition Against Daesh (a.k.a. the Coalition) has been involved in approximately 16% of total events reported in the country. In both of these contexts, the coalition engages primarily in airstrikes, often in support of domestic forces. By contrast, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) in Afghanistan and the Coalition in Syria are engaged in relatively lower proportions of events in those countries – a function of the goals of the coalition in Afghanistan and the complexity of the crisis context in Syria. In Afghanistan, NATO operates almost solely in a supporting role, rarely acting unilaterally. In Syria, the Coalition engages in strikes as well, though is also increasingly engaged in ground combat too.

But coalitions are not monolithic. The activity of specific state actors within a coalition can vary in terms of the activities in which they engage as well as the spaces in which they are active in the country. The divergent political interests of the participant countries in coalitions can hence manifest as varied engagement in the conflict landscape. For example, in Yemen, as a part of Operation Restoring Hope, Saudi forces are responsible for the majority of air and ground operations with the highest level of engagement centered primarily in northern Yemen, along the border, and in the south-eastern provinces; UAE forces, on the other hand, are engaged primarily through support and sponsoring of the creation of local security providers and pro-independence political bodies in the south as well as the coastal Tihama region; Sudanese forces, meanwhile, act primarily in support of military operations in southern Saudi Arabia, as well as in northwestern Yemen and the western coastal plains. In Afghanistan, NATO forces are nearly synonymous with American forces given the level of involvement of the US, whose activity is largely composed of remote violence tactics in support of the Afghan military; their activity is clustered largely in a small number of border provinces. In Iraq, and to an even greater degree in Syria, American forces are the most active of the Coalition partners, and specifically US Special Forces have the greatest ground presence in the countries (allegedly to advise local actors), by contrast to other Coalition partners who largely restrict their involvement to air support.

As a result of their varied engagement, how coalition actors are perceived on the ground by local populations can also vary, and can contribute to heightened tensions. Perceptions can be especially damning when the actions of the coalition reflect their own incentives and/or result in direct harm to civilians. In Yemen and Syria, for example, the coalitions are responsible for relatively high levels of harm to civilians; in Yemen, Operation Restoring Hope has been the main perpetrator of violence against civilians in the country, and in Syria, activity of the Coalition has resulted in five times as many instances of civilian targeting when compared to their engagement in Iraq. This has resulted in heightened tensions in both countries and negative views of the coalition by the local population. In contrast, such views have been less reported in Afghanistan; this may be a function of NATO’s minimal reported engagement with civilians in their actions, as well as the fact that given NATO’s relatively longer tenure in Afghanistan relative to other coalitions in the Middle East, NATO may be viewed as a ‘fact of life’ for the local population.

These facets of coalitions mean monitoring their activity can be difficult, and requires a flexible yet systematic methodology to ensure accurate portrayal of their engagement in these conflicts. A large number of states may be active in a single coalition, though it may not always be clear which state carried out a specific attack under the coalition umbrella. This could at times be attributed to reporting; some coalitions publish press releases around their activity, others do not; some local organizations are able to identify the engagement of specific actors, though this is not always the case. However, arguably more often, this anonymity is strategic rather than a reflection of reporting capacity as a specific state may wish to distance itself from its activity. As such, it is imperative to not introduce bias into the data collection. Attributing only the events in which the specific actor responsible is unknown to the coalition would do so as this subset of events is not random, and would hence result in painting a different picture of coalition activity than what may be the reality.

Given these complexities in collecting information on conflict patterns and trends, ACLED follows these methodological decisions in collecting materials:

In cases involving coalition actors acting unilaterally, regardless of whether it is known who the primary actor is or not, the coalition itself is coded as the primary actor (e.g. “NATO: North Atlantic Treaty Organization” as primary actor). In cases where it is known who the specific state actor was as well, this state actor is coded as the associated actor to the coalition actor (e.g. “Operation Restoring Hope” as primary actor, with “Military Forces of Saudi Arabia” as the associated actor). Given that coalition actors are, by definition, external forces, they are coded with an interaction of 8 in the dataset.

When a coalition actor is acting in support of domestic state forces, the domestic state forces are coded as the primary actor, with the coalition actor as its associated actor (e.g. “Military Forces of Iraq” as primary actor, with “Global Coalition Against Daesh” as the associated actor). This assumes that the coalition actor is active within the country in a supporting role to the domestic state forces, and so the state forces define the interaction within ACLED’s coding structure. In cases where a known coalition actor is supporting the specific domestic state actor, this actor is included as an associated actor as well (e.g. “Military Forces of Iraq” as primary actor, with “Global Coalition Against Daesh; Military Forces of the United States” as the associated actors).

The coding of specific coalition members as associated actors is done conservatively. If it is unknown or uncertain who the specific actor may be, they are not coded as associate agents. Even in those contexts where it is fairly apparent who the specific actor may be (e.g. in Afghanistan, it is primarily the case that NATO drone strikes are American), if there does not exist a specific report to point to, an assumption is not made and the specific actor is not coded. This is in an effort to not dilute the cases in which it can be expressed with certainty who the actor may be. Those working with the data can choose to be more liberal with their assumptions should they wish and can re-categorize such associated actors as desired.

This coding structure allows for both analysis of coalitions at large, as well as specific coalition members.

In a three-part series, coalitions currently active across the Middle East are explored, capitalizing on the flexible yet systematic methodology introduced above to better understand conflict patterns associated with coalitions in the spaces in which they are active.

These three coalitions and contexts include:

- Operation Restoring Hope in Yemen

- The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) in Afghanistan

- The Global Coalition Against Daesh in both Syria and in Iraq

The varied levels and modes of engagement of coalition actors, as well as of specific state actors within coalitions, highlight the nuances and complexities of exploring the patterns of violence associated with these actors. ACLED methodology and coding practices around capturing these patterns — coupled with weekly data releases supplemented with information from local conflict observatories — allow for researchers to explore these dynamics in near real-time.