As pressure from UAE-backed troops and US airstrikes has increased over the past two years, Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) fighters have found themselves engaged on multiple fronts, weakening their ability to control and manage territory. While AQAP remains a major threat to Yemeni society, a decreasing number of claimed operations by the group suggests that their ability to conduct attacks and coordinate bombings has diminished.

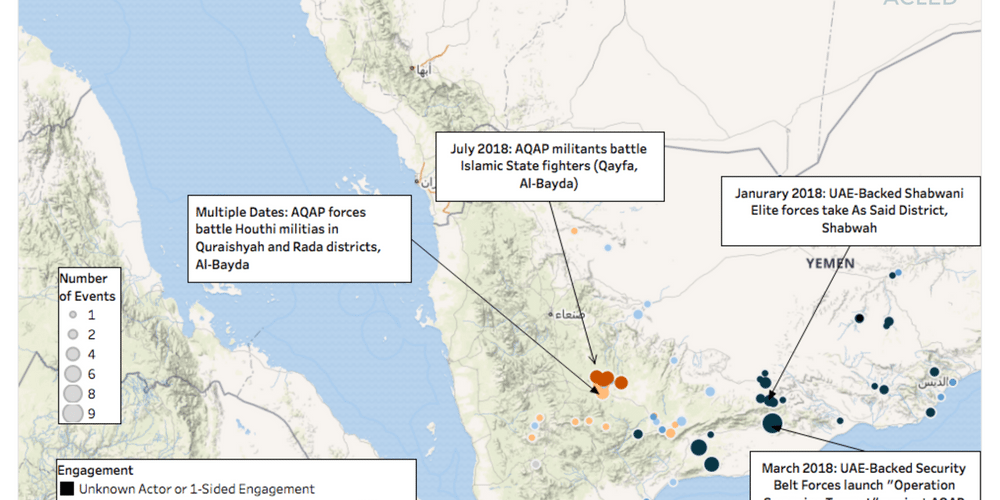

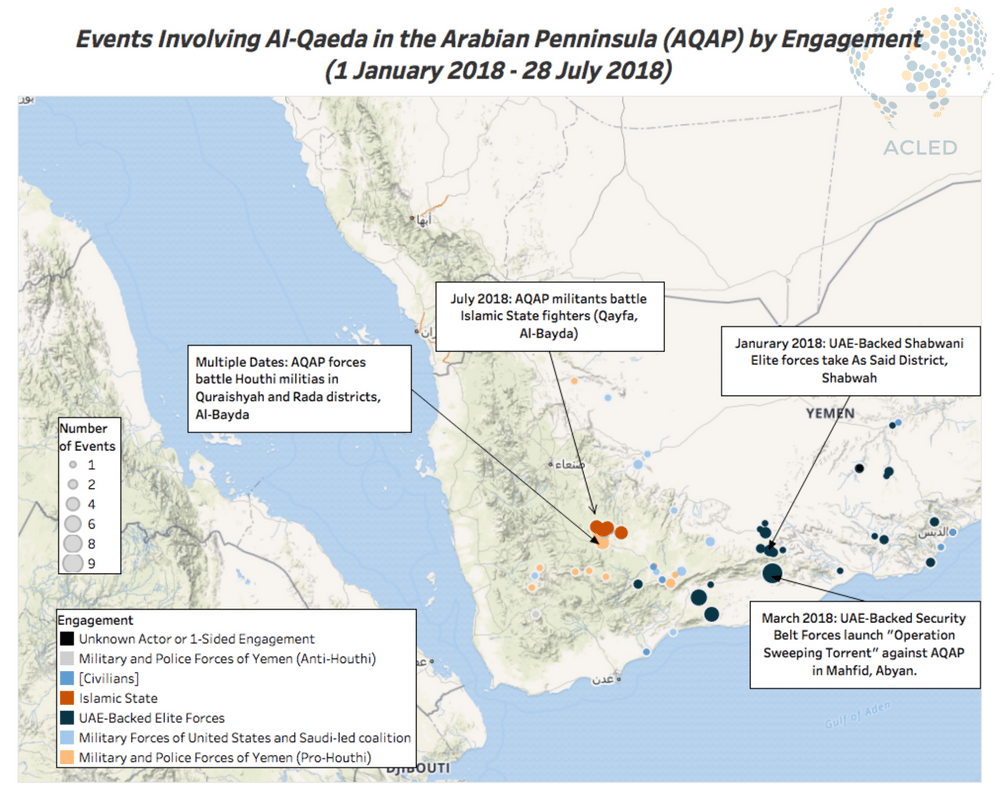

Currently, fighters from AQAP are engaged in battles along multiple fronts. Data over the past two years show that AQAP is actively fighting UAE-backed special forces; Al Houthi affiliated militias; Yemeni government troops loyal to the internationally recognized president Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi; as well as other jihadi militant groups, including Islamic State linked militants. Frequent airstrikes conducted by US drones and Saudi-led coalition warplanes have also degraded the group’s ability to operate freely. (See the map below, detailing the locations and actors associated with these events.)

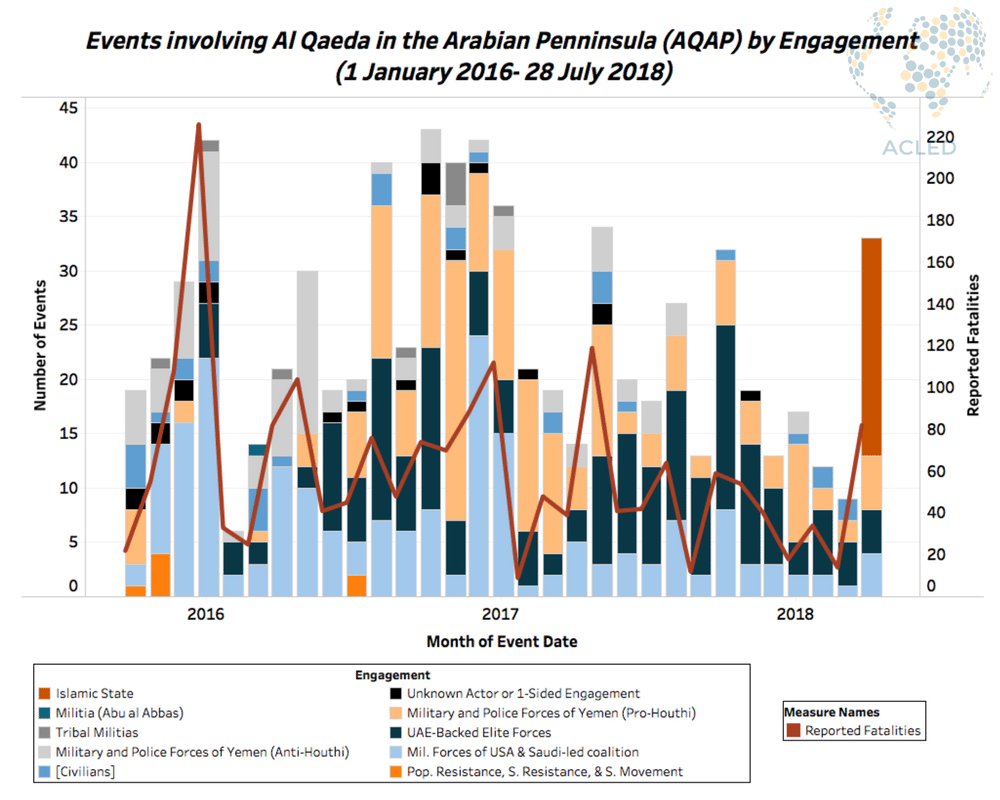

Despite AQAP appearing weaker than it has ever been, the group remains deeply embedded within areas that are threatened by advancing Houthi militiamen as they present a well-armed and experienced fighting force capable of countering Houthi advances. In the 2017 calendar year, excluding airstrikes, AQAP reportedly engaged with Al-Houthi linked forces at least 112 times, making up around 44% of their reported activities. In remote locations along the frontline (such as the tribal regions in Al-Bayda), “tribesmen are motivated by a commitment to protect their land and homes from the Houthis” and have occasionally coordinated with AQAP to combat their common enemy (Project On Middle East Democracy, February 2018).

AQAP leaders have used their position as a fighting force in anti-Houthi areas in an attempt to further increase their local influence and appeal. Unlike other Al Qaeda affiliates such as Al Shabaab in Somalia, AQAP rarely, if ever, use violence against local civilians under their control. When tribesmen were accidentally killed as ‘collateral damage’ in operations designed to target the Yemeni military, AQAP published apologies and negotiated to pay ‘blood money’ (Washington Post, 23 February 2018). Despite these attempts, local populations are aware of the risks of affiliating with Al Qaeda and most disagree with the group’s violent aims (Project On Middle East Democracy, February 2018). Furthermore, the United States is committed to countering AQAP in Yemen (see ACLED, 13 June 2018), and airstrikes frequent areas under their control, leading locals to resent AQAP presence in their towns and villages.

In 2018 thus far, AQAP has most frequently engaged in clashes with local elite groups trained and backed by the UAE (see ACLED, 9 March 2018), representing a significant change from the previous year during which most operations targeted Houthi forces. Since taking the city of Mukalla from AQAP control in late April 2016, the UAE has conducted “an ambitious recruitment program” across much of South Yemen in order to enlist fighters in countering the group (Middle East Institute, July 2018). These groups of elite forces have expanded especially over the past year with operations designed to drive militants from areas that have long held an AQAP presence, including the governorates of Shabwah, Abyan, Hadramawt, and Lahij (WAM, 11 March 2018; The National, 25 March 2018).

Activity involving AQAP has been steadily declining since peaking in the earliest months of 2017 (see graph below). A recent uptick in activity during the month of July 2018 was due to a series of violent clashes between AQAP militants and Islamic State fighters, which have since subsided. This uptick does not likely represent a return to 2017 levels of activity, but rather could suggest a diminishing ability to make and maintain alliances, further evidencing a degraded organizational structure. Despite being weakened territorially by UAE Elite troops and US drone strikes, however, the conditions that contributed to AQAP’s rise in Yemen – sectarian violence and abuses by the central government – remain. Until these root causes are properly addressed, AQAP will likely continue using Yemen as a base for operations.

Find an explanation of ACLED’s methodology for monitoring the conflict in Yemen here.

AnalysisCivilians At RiskFocus On MilitiasIslamic StateIslamist ViolenceMiddle EastPro-Government MilitiasUnidentified Armed GroupsViolence Against Civilians