On 12 November, the government of South Sudan, the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement – In Opposition (SPLM-IO) rebellion, and a raft of smaller armed and unarmed groups are expected to form a Transitional Government of National Unity, under the Revitalized Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in South Sudan (R-ARCSS, signed in the Sudanese capital Khartoum in September 2018). With progress on the most significant pre-transitional milestones lagging far behind schedule, SPLM-IO rebel leader Riek Machar threatening to withhold his participation in the Transitional Government, and President Salva Kiir insisting that the deadline be met, the ingredients for an unravelling of the peace accord seemed to be in place (Sudan Tribune, 21 October 2019).

A last minute intervention by the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) heads of state in Entebbe, Uganda, saw the two men agree to a 100-day extension of the pre-transitional period, with a review scheduled 50 days into this extension (Eye Radio, 7 November 2019). This was justified by Salva Kiir the following day on the grounds of averting renewed war with the SPLM-IO, and because of the government’s own failure to disperse funds necessary for logistically complicated parts of the agreement (Radio Miraya, 8 November 2019). The president further noted that he had to accept to “persuasion” of the peace guarantors (Uganda and Sudan), and that a new committee to monitor progress was to report to the guarantors. He also alluded to the possibility of further extensions being required, in the event of insufficient progress. With this second extension (following an earlier six-month extension in May), South Sudan remains in a state of suspended animation. It is not clear where the pieces will ultimately fall, and this uncertainty is causing concern (and frustration) among some observers and diplomats. The spectre of a return to the heavy fighting that rocked the South Sudanese capital, Juba, in July 2016 underpins many of these fears, and perhaps too a deeper sense of despair at the prospects for a meaningful and orderly peace to take root in the near future. This extension provides an opportunity to reflect on South Sudan’s trajectory under R-ARCSS. Are fears of a power struggle and violent collapse well-founded? And are there indications that South Sudan’s profoundly abusive power structures are likely to change for the better?

The Revitalized Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in South Sudan (R-ARCSS)

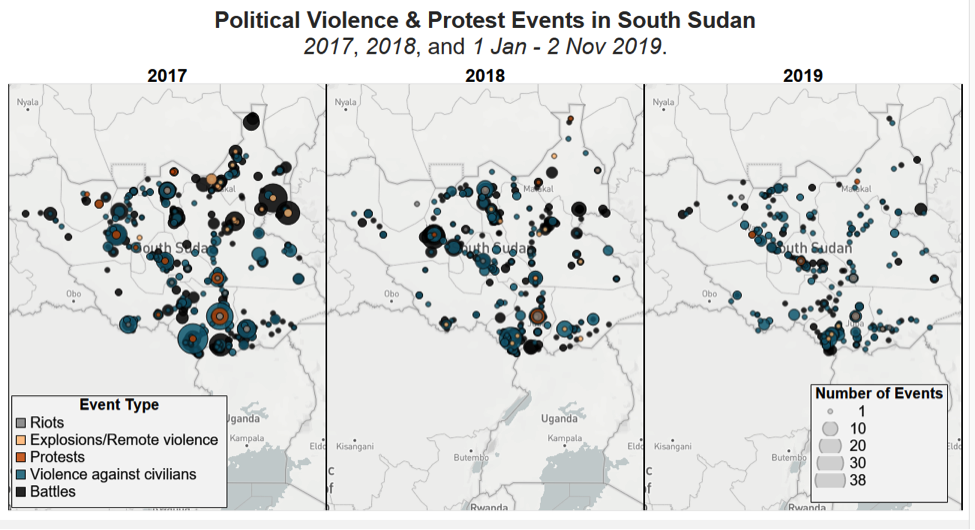

The R-ARCSS differs from its 2015 successor in two important respects. First, the 2015 Agreement (ARCSS) served to exclude regional powers from South Sudan, notably Sudan and Uganda. R-ARCSS brings these two countries back in, albeit as guarantors of the peace. Second, the original ARCSS brought together a reluctant government and SPLM-IO under intense international pressure, with both parties severely testing both the letter and spirit of the agreement (the SPLM-IO through abusing the cantonment process to expand its influence, and the government through dodging security requirements in Juba, and unilaterally replacing the 10 administrative states with 28 states, and then 32 states). This time, a wider ensemble of military and political players are included, in what is an otherwise similar agreement. Most importantly, the government under Salva Kiir is more at ease with the degree of its control over the military and political structures of the country, though it urgently requires the economic benefits that peace may bring about, particularly ensuring good economic relationships with Sudan and to a lesser extent Uganda. R-ARCSS has coincided with an overall decrease in organized political violence events in the country (see map below). However, whilst there has been a pronounced decline in battles involving rebels, violence — including by rebel groups — has continued.

The implementation of the peace agreement depended (in large measure) on Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir exerting his power over Salva Kiir and Riek Machar, to break impasses or wavering from the terms of the agreement. Bashir could draw upon his close connections with both men to uphold the agreement until a transitional government solidified, and utilise former National Congress Party officials which are now embedded in Salva’s administration. With his overthrowal in April of this year, however, enforcement of the agreement has been left to Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni — who has a much stronger relationship with Salva than with Riek. Moreover, the upheaval in Sudan has caused a broader anxiety about the solidity of South Sudan’s political system. South Sudan’s post-independence configuration resembles its northern counterpart in several important respects, notably in its elite-centric economy and the dominance of multiple security organs over society at large. This makes it vulnerable to both civil disorder as well as a coup from the armed forces, even if these would likely play out in different ways in South Sudan. Furthermore, the risks of a deterioration in the security and economic relationship between the two countries entails uncertainty in the South Sudanese governing system. This system currently operates with a limited capacity for change, and when changes exceed narrow parameters, disorder and a revision of elite calculations can occur. Such a fraying could imperil the stability of Juba, and embolden armed groups either side of the border seeking to exploit tensions between the two countries.

These fears have eased with the establishment of a relatively lengthy (and still military-dominated) transitional government in Khartoum (International Crisis Group, 21 October 2019). This is a welcome outcome for Juba, which is currently reliant on continuity and stability in Khartoum. The relationship is being further consolidated through the active role that Juba, under Presidential Security Advisor Tut Gatluak, the adopted son of Omar al-Bashir, has taken in the peace negotiations between Khartoum and the assorted rebel groups in Sudan’s peripheries. Nonetheless, important internal issues within South Sudan have haunted the implementation of the pre-transitional phase of R-ARCSS. These issues include the cantonment, retraining and integration of the belligerents; the establishment of a VIP protection force; and a final determination on the number of states in South Sudan. The latter entails a workable arrangement for governing the cities of Wau and Malakal, amidst competing ethnic claims for control, and for apportioning territory that sits atop oil fields. Cantonment, meanwhile, has suffered from ambiguity with regards to its purpose, as well as lack in essential items availed for rebel forces by the government and donors.

There has been very limited progress across these issues. This is arguably due to the lack of imperative or pressure felt by the belligerents – and particularly the government – to make compromises on them. Further, there are potentially high costs to important constituencies in both the rebel and government camps were concessions to be made. It is unclear at this point whether the new 100 day extension will provide the impetus for parties to decisively resolve these points of tension.

State of Play of Different Rebel Movements

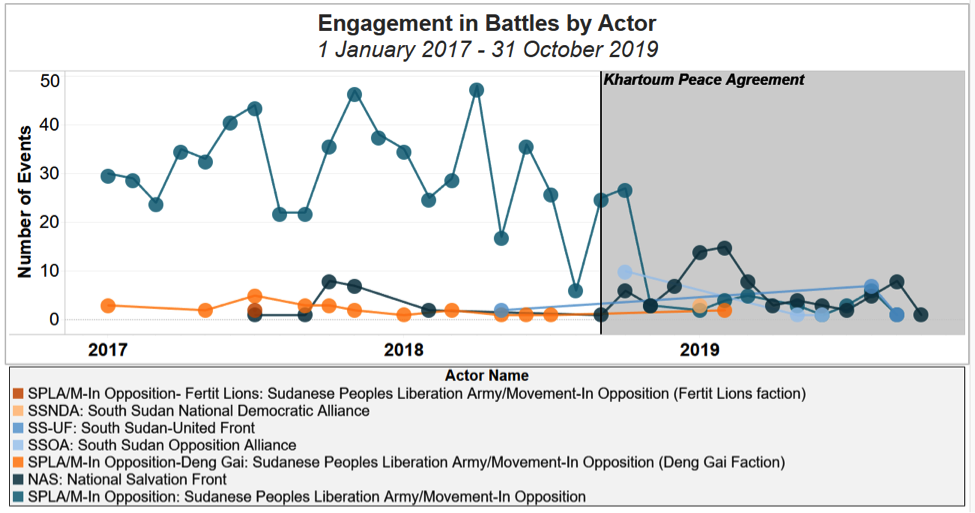

In the event of a total or (more plausibly) partial or gradual collapse of the R-ARCSS, might there be a return to mass violence? Although this is the most disturbing scenario, any assessment must acknowledge that all rebel groups exhibit a diminished capacity for violence (see graph below), whilst the government is holding most of the cards. Both the South Sudan Opposition Alliance (SSOA) and elements of the South Sudan National Democratic Alliance (SSNDA) are embroiled in damaging leadership disputes, and the presence of relatively autonomous commanders degrading the coherence of the largest rebel group, the SPLM-IO. Most importantly, all groups lack the external patrons that have traditionally underpinned the more powerful rebellions of previous rounds of fighting during and after the Second Civil War. This greatly benefits Salva Kiir’s government, who, in addition to monopolizing oil resources and territorial presence, can deal with any threats posed by rebel groups without much risk of antagonising regional powers, so long as their interests are protected.

The largest (and most diffuse) rebellion remains the SPLM-IO. Clashes between IO forces and the government have declined considerably, following flare-ups in fighting in Western Bahr el Ghazal, which stalked the progress made in the Khartoum peace negotiations across the summer of 2018. The IO continues to suffer from fractures and poor coordination between the largely Nuer components of the rebellion, led primarily by ex-South Sudan Defence Forces commanders from the previous civil war, and more disparate groups from the south and west of the country that attached themselves to the rebellion after the signing of ARCSS in 2015. These are joined with the greatly weakened Shilluk forces under Maj. Gen. Johnson Olonyi, that at one time seriously challenged the government for control of Malakal. Although not necessarily a portent of things to come, fighting was reported in the eastern area of Maiwut in late July and early August within the Nuer elements of the IO. These clashes precipitated the defection of rebel commander Maj. Gen. James Ochan to the government, and the firing of rebel governor Stephen Pal Kun. This suggests that maintaining integrity among the Nuer core of the rebellion is crucial to maintaining the structural integrity of the movement as a whole, and that a failure to do so may be the undoing of the IO (Radio Tamazuj, 30 September 2019).

In addition to the questions regarding the coherency of the movement, which are themselves bound up in a lack of trust between various elements of the IO and Riek Machar, the cantonment process has exposed problems in the military capacity of the rebellion. The IO has long suffered from an inability to reliably procure weaponry, largely due to the lack of significant external support, as well as gradual desertions by Nuer soldiers. The other armed signatory to the agreement, the SSOA, has little in the way of proven military capacity (Institute for Security Studies, December 2018). Moreover, with the death (by natural causes) of Maj. Gen. Peter Gadet earlier this year, the SSOA has lost its most credible military commander and mobiliser. The relatively limited numbers of IO and SSOA rebels (and crucially, armed rebels) who have arrived for cantonment (CTSAMM, 29 October 2019) indicates three things. First, that the groups have been exaggerating the size of their forces during security negotiations. Second, that at least some of those registered at cantonment sites are civilians posing as combatants. And third, that certain units of the IO are not participating in cantonment, likely over concerns about the government’s intentions and failure to meet its own cantonment commitments (International Crisis Group, 4 November 2019).

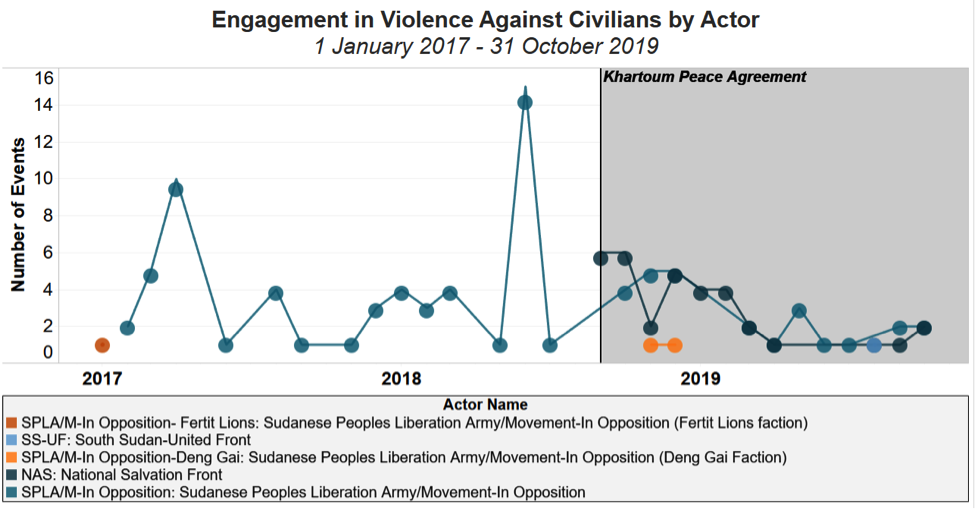

Of the non-signatories to R-ARCSS, the National Salvation Front (NAS) rebels under Lt. Gen. Thomas Cirilo remain the only group with a demonstrable capacity to engage in sustained organized violence. However, the NAS has only engaged in sporadic clashes with state security forces in Central Equatoria state in recent months. These include a battle in Morobo county which killed three IOM volunteers and an unknown number of combatants, as well as limited clashes with National Security Service personnel near Lobonok, reportedly over control of a mine). The infrequency of the attacks suggests that the governments’ ruthless counterinsurgency campaign of late 2018 and early 2019 has dislodged the NAS from their positions, and stunted their ability to engage in serious operations against the government or SPLM-IO rivals (UNMISS, 3 July 2019). This has, however, been offset with more frequent attacks by NAS rebels (as well as government forces) against civilian targets (see graph below).

Finally, in late August the South Sudan United Front/Army (SSUF/A), headed by former army chief Lt. Gen. Paul Malong, engaged in several clashes with government forces around Raja town in the former Western Bahr el Ghazal state. The clashes followed from the SSUF/A’s reported expulsion from Sudan and/or the Central African Republic. Reports indicate that the clashes did not go in the rebel’s favor (CTSAMM, 29 October 2019). Concurrently, Malong negotiated an unlikely agreement with long-time rivals Lt. Gen. Oyai Deng Ajak and Pagan Amum, as well as the holdout rebel coalition, the SSNDA (chaired by Thomas Cirilo) (PaanLuel Wel Media, 30 August 2019). A loose alliance between elites whose influence has been declining in past years, operating alongside a weakened rebel coalition, will not – at least in the present circumstances – be a source of serious concern to the government.

Actual and potential violence from rebels has therefore been significantly curtailed, or else compartmentalized and concentrated within specific factions of groups. Yet a greater danger may lie in the interaction between rogue elements of both rebel groups and the military apparatus on the one hand, and irregular youth militias on the other. Since the 1980s, destructive and sometimes intractable fighting between irregulars has been the toxic residue bequeathed by government counterinsurgency strategies and inter-rebel struggles, both of which have involved in distributing weaponry to rural young men. This has violently fused neighboring sections of many Dinka and (particularly) Nuer clans together in often ruinous raiding and retaliatory strikes, and increased predation upon civilians in many parts of the country (Sharon Hutchinson, 2001). Further, this has set the stage for patterns of violent disarmament and temporary re-armament from government forces from 2005 onwards. In 2019, raiding and violence by irregulars has been recurrent mainly in Western Dinka regions, including the former Lakes state, Kuajina county of the former Western Bahr el Ghazal state, and the disputed Twic, Tonj, and Gok states. Such violence may intensify in the event of further tensions among Bahr el Ghazal Dinka elites (Africa Confidential, 6 April 2018), and may be matched in other regions of the country where armed youth are mobilized by disgruntled IO commanders. Recruitment activities by such commanders provide a clear warning sign for such violence (Sudan Tribune, 10 May 2019).

The Future of Violence in South Sudan

Salva Kiir has prevailed in the grinding wars since 2013, defeating a successive array of military and rebel contenders, albeit at tremendous human and economic cost. The military advantage currently enjoyed by the government and its army, the South Sudan People’s Defence Forces (SSPDF, formerly Sudan People’s Liberation Army, SPLA), is not something they will be prepared to sacrifice. This is exemplified by their refusal to fully adhere to their cantonment commitments, with the exception of forces which have been cantoned in the northern town of Renk. Furthermore, the government’s failure to provide basic supplies to numerous cantonment sites occupied by SPLM-IO and SSOA rebels indicates its refusal to divert limited resources to rival forces. There is little reason to expect this to substantially change, whether or not Riek joins the government.

Whatever happens in 100 days’ time, there are grounds for cautious optimism that mass violence on the scale of December 2013 and the first half of 2014 is unlikely to return. More bleakly, neither is it likely that a transition from the violent, paranoid and militarized system at the core of South Sudan’s governing structures will occur either. A lack of military and economic resources, as well as a coherent opposition, precludes sustained destruction and collective ethnicized punishment of the intensity seen at the start of the current war. This also blunts the ability of would-be warlords to mobilize and hold large areas. Conversely, the government has made strides in consolidating its control of the security apparatus, and has become relatively adept at manipulating the system to survive, if not to thrive.

The immediate risks are as follows: limited military operations and clashes within specific flashpoints of the country, most likely around the cities of Wau or Malakal; predation in areas around cantonment sites from hungry or disillusioned soldiers; mobilization of irregular militiamen by dissident commanders; and clashes between bodyguards of the President and numerous Vice-Presidents. Juba is an obvious flashpoint for such clashes, particularly if the large numbers of bodyguards are brought to the same location for a meeting among the leadership (Africa Centre for Strategic Studies, 12 January 2019). Certain combinations of bodyguards carry heightened risks of violence. Bringing Salva’s and Riek’s bodyguards together, or current First Vice-President Taban Deng’s guards with Riek’s, may spark serious urban fighting, whilst protection details of other Vice-Presidents are less likely to cause trouble, Incidentally, the risk of such fighting somewhat diminishes if Riek does not take up his post of First Vice-President. Whether or not Riek relocates to Juba by next February, a plausible scenario would be for the existing cabal around Salva Kiir to continue running the government under a façade of power-sharing unity administration, with periodic conflict or defections failing to dent the system as a whole, unless they pile up and begin to overwhelm the functioning of the politic-military structures undergirding the current political order (United States Institute for Peace, 7 October 2019).

The vital question is whether these scenarios, especially clashes over contentious cities or between bodyguards, will escalate in similar ways to December 2013 and July 2016. Much rests on the degree to which South Sudan’s political system remains beholden to powerful individual leaders and their rivalries. If there has been a return to an earlier era of partial institutionalization of the army, and more effective relations between senior generals and commanders on the ground, then the potential for leadership disputes to boil over is considerably reduced. Consultations with senior generals may stop provocative or rash decisions being made in the first place, whilst brokers can help hold together a situation in the event of a political breakdown. The presence of credible generals and respected senior veterans who hold sway across both SSPDF and rebel lines will greatly reduce the tensions and risk of violence that accompanies political brinkmanship and missteps. For this to happen, establishing a balance between the executive and military institutions is crucial, as is the need for government and incoming rebels to establish trust and effective working relationships. In a system notorious for paranoia and damaging defections which typically result in violent fallout, this must be carefully arranged so that one party does not attempt to seize power from the other, or take actions that have the appearance of preparations to neutralize the other.

Although the origins of the current civil war are often explained as being a by-product of tensions at the top of the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement party in 2013, particularly between Salva and Riek, less remarked upon is the deteriorating relationship between the executive and the army that preceded such tensions. A lack of trust permeated these relations, reinforced by efforts by the Presidency to undermine SPLA procedures and coherency through integrating militias and reintegrating military defectors (Lesley Anne Warner, 24 December 2013). Most troublingly, the growth of praetorian guards during this time exacerbated these problems, creating new divisions between regular forces and new security organs directly controlled by the Presidency. These praetorian units included irregulars such as Dut Ku Beny (Naomi Pendle, October 2015), or regular forces in the form of the National Security Service, which has continued to enhance its power and reach in the course of the civil war (United Nations Security Council, 9 April 2019). This process of de-institutionalization and divisions created an environment to enhance the power of more belligerent elites, notably Paul Malong. If a gradual re-institutionalization of the military takes place this may, paradoxically, create faint openings for a (limited) civilianization of South Sudanese politics, and more stable and orderly methods for regulating power struggles. This might presage a much-needed transition from the self-perpetuating militarism and authoritarianism that looms over the country. This malaise has been present in the rebel movements of the war that led to South Sudan’s independence, and lives on in an exaggerated form today. Resolving these deep-rooted problems is vital if the country is to have the relief from misery it so deservedly needs.