The addition of data sourced directly from the Taliban more than doubles the number of events recorded by ACLED in Afghanistan, and allows deeper insight into how and where the Taliban exerts strength.

Introduction

The conflict in Afghanistan is one of the deadliest in the world (ACLED, 2019). The country features an insurgency led by the Taliban which has persisted in its current form for nearly two decades. Taliban forces maintain control in some areas of Afghanistan, while other armed groups – such as the Islamic State – are increasingly complicating the conflict landscape and making inroads across the country (ACLED, 2018).

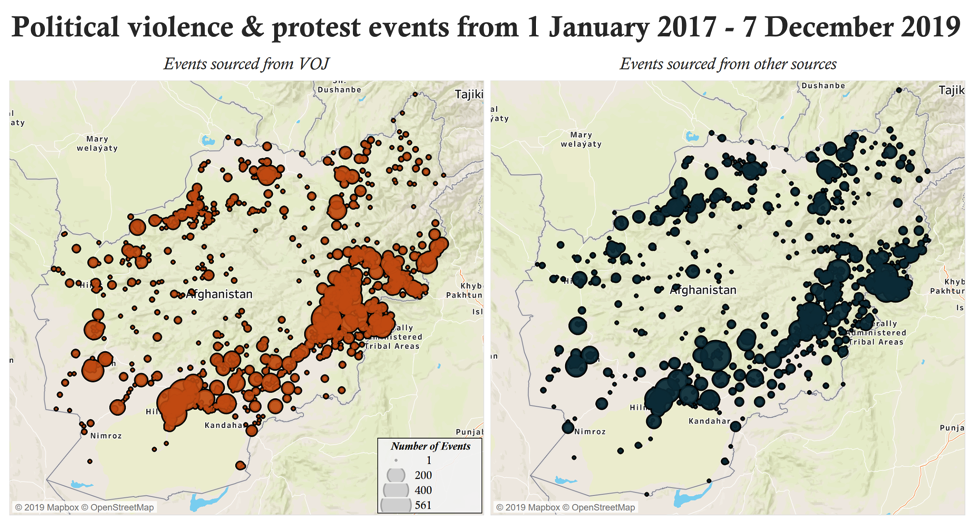

To better represent the ground reality of this complex and enormous conflict, the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) has supplemented coverage of Afghanistan with over 21,000 additional events sourced from Voice of Jihad (VOJ), a website and news service run by the Taliban. The addition of VOJ as a source for Afghanistan more than doubles the number of political violence and protest events in ACLED’s Afghanistan dataset (see map below), offering more nuanced insight into the conflict landscape.

Being run by one of the parties to the conflict, VOJ is obviously not a neutral source of information. What makes the source particularly useful in the Afghan context, however, is that information provided by VOJ is often not reported elsewhere. The combination of the conflict’s complexity with the country’s rough terrain makes coverage in certain areas by traditional media largely impossible — which is why many of the journalists active in Afghanistan also rely on VOJ for information (for example: Pajhwok, 7 May 2019[1]; Afghan Islamic Press, 19 April 2019[2]; New York Times, 15 May 2018[3]; Pajhwok, 3 September 2019[4]; RFERL, 7 June 2013[5]; Washington Post, 9 September 2019[6]; Long War Journal, 23 August 2018[7]).

Analytically, VOJ data give a more complete picture of the Taliban’s situational circumstances, in particular lending unique awareness of where the group may operate support zones and maintain areas of strength and lower-scale activity. Such insight increases both the scope and the quality of the ACLED situational overview of Afghanistan. Given the Taliban is a conflict party, and reports from a conflict party come with many biases, additional steps are taken in ACLED’s coding process to ensure the reliability of these data. Such steps are detailed in this ACLED primer on coding methodology in Afghanistan.

VOJ Data Addition: An Overview

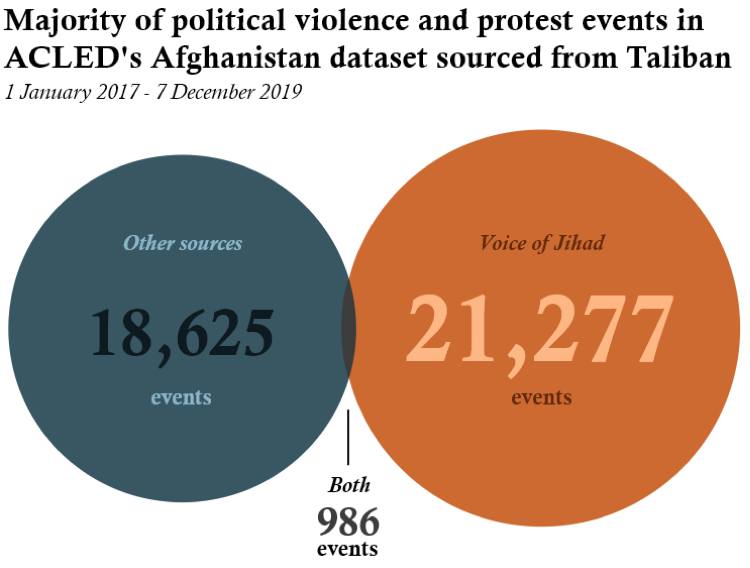

The addition of information from VOJ has more than doubled ACLED’s Afghanistan dataset, from fewer than 20,000 events to over 40,000 (see diagram below). Coverage extends from 1 January 2017 through the present.

VOJ’s coverage expands beyond events in which the Taliban were directly involved, though a large majority involve the Taliban as either a primary or secondary actor. Of the more than 34,000 events which involve the Taliban since the start of 2017, nearly two-thirds come from VOJ. Unsurprisingly, the top authority on the Taliban is the Taliban itself.

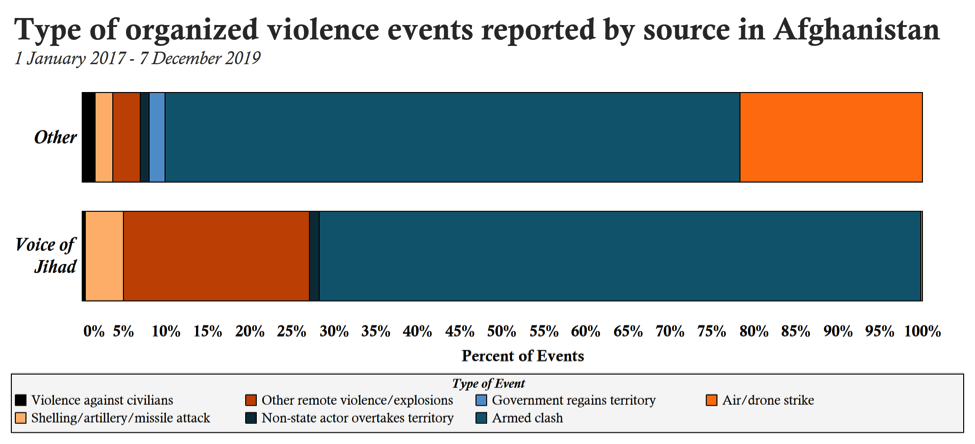

Similar to other sources covering the conflict in Afghanistan, VOJ reports a majority (roughly two-thirds) of events as battles, especially those with no exchange of territory. Where VOJ varies is in its emphasis on coverage of remote violence involving explosives (see figure below), as well as its coverage of events it claims are perpetrated by the Taliban. This is unsurprising: conflict actors typically have an incentive to appear strong and will emphasize reporting which corroborates this image. Relatedly, VOJ reports zero events in which the government retook territory, while other sources (including the Afghan Ministry of Defense [MOD]) report over 250 such events. This again indicates a reluctance on the part of the Taliban to report losses.

A comparison of engagement types brings similar differences to light. The Taliban, for example, reports a considerably higher proportion of events in which they engage with political militias (in particular, militias loyal to the Afghan government). Other sources, namely the Afghan government (MOD), do not report as many of these events, possibly in an effort to minimize the role played by such militias. Governments will often downplay their links to purposefully clandestine agents (for more on pro-government militias, see Raleigh & Kishi, 2018). Likewise, non-VOJ sources report over three times the number of civilian targeting events perpetrated by the Taliban compared to VOJ. This could point to the Taliban’s desire to build or maintain popular support and establish legitimacy (ACLED, 16 May 2018).

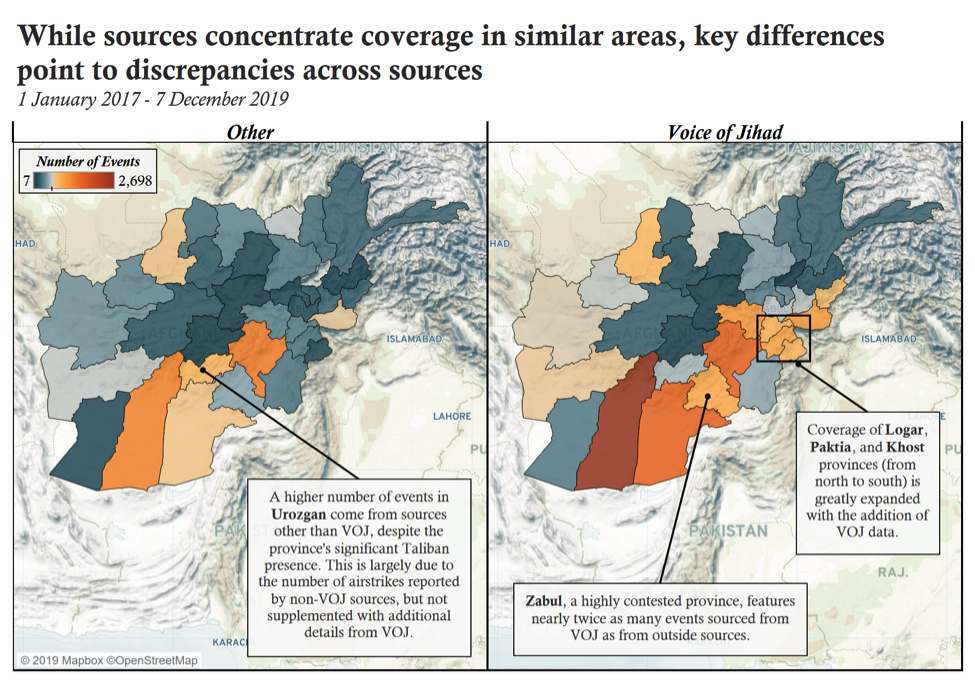

On the surface, events reported by VOJ versus by other sources have similar geographical dispersion. Both exclusively VOJ-sourced events and those not reported by VOJ have occurred across just over 1,000 distinct locations across Afghanistan, and are generally concentrated in similar areas. However, a closer look at the geographical disparity between these sourcing patterns reveals distinct differences. In short, Taliban sources report events in ‘the places in between’ – skirmishes along supply routes, clashes at checkpoints, and other lower-intensity events between larger population centers, important targets, or provincial capitals. Through examining such events, one can garner insight into possible Taliban support zones and lines of effort outside of major campaigns, as well as more detailed information from areas with higher Taliban presence and strength.

VOJ’s Added Value is Showing the ‘Places In Between’

VOJ data provide the opportunity for analysts to view not only an expanded number of events involving the Taliban, but gain insight into specific operations and campaigns as they occur, as well as the Taliban’s use of space and geospatial patterns of attack.

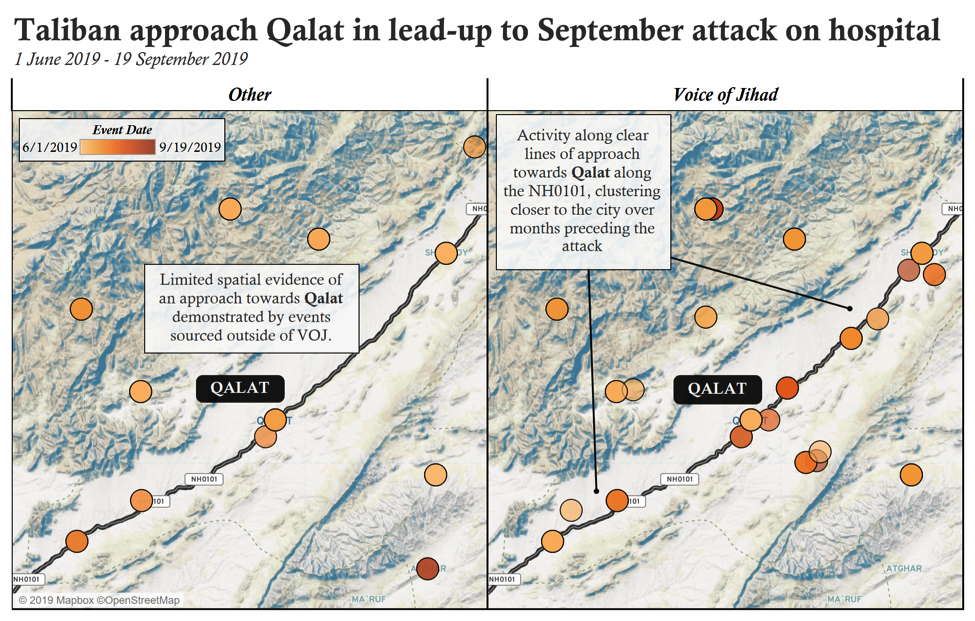

For example, on 19 September 2019, Taliban forces used a car bomb to attack a hospital in the city of Qalat in Zabul province in southeastern Afghanistan (labelled on the map to the right). Both the Taliban and other sources reported this attack. However, the activity during the months before and in the areas surrounding this attack look very different across these source categories. Below, two maps portray events between June and September 2019 surrounding Qalat, with events colored in darker orange as it gets closer to the bombing on 19 September. The first map (on the left) shows events reported outside of VOJ, while the second map (on the right), shows events sourced from VOJ.

The differences between the two maps demonstrate a common pattern between VOJ and non-VOJ sourcing. Non-VOJ sources independently report 87 events across about a dozen locations during this time period in the areas surrounding Qalat. In contrast, the VOJ reported nearly twice as many events, across roughly twice as many locations, during this time. The events differ in their timeframe as well: the Taliban reported far more events in the weeks directly before the attack. Moreover, those more recent events clustered nearer to the site of the actual attack, and they occurred along lines of movement: the NH0101 road passing through Qalat draws a very clear line directly tracing the Taliban’s movements during this time period, giving insight into their use of infrastructure in the leadup to this attack. Additional Taliban activity can be seen in a small cluster to the southeast, as well as on the western side of the mountain range to the north. These Taliban-reported events largely target police posts and government positions, and cover both the areas where the attack occurs and from where they launch the attack. Reporting provided by the Taliban’s own sourcing provides evidence, in time and space, of the Taliban’s emphasis on the area in the months before the major attack took place.

VOJ data also provide unparalleled access to Taliban movement within contested and Taliban-dominated areas. VOJ-sourced events often cluster within areas where the group is generally strong, and is often on the offensive.

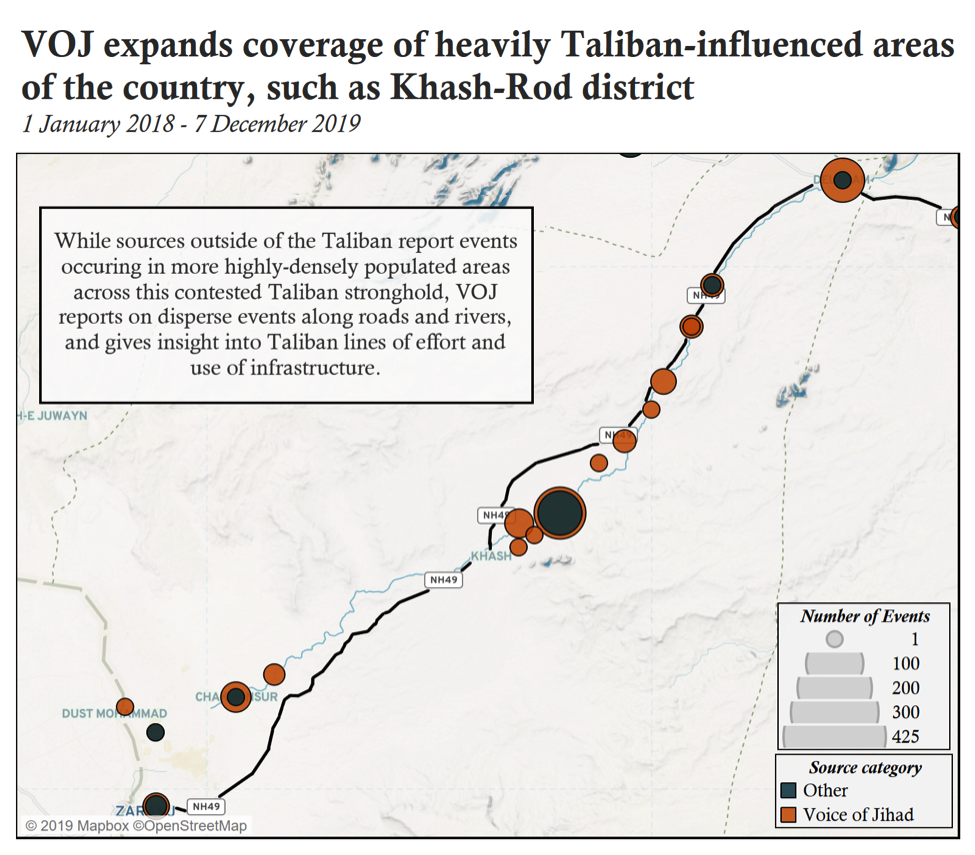

In another example, the map below shows Taliban activity in Khash-Rod district in Nimruz province in Afghanistan’s southwest. The area is largely considered to be contested (Long War Journal, 2019), and remains an area of substantial Taliban activity. While sources outside VOJ report events across relatively few locations in this region, Taliban sourcing shows clear presence along natural and administrative boundaries and infrastructure over the past two years. These events – along the NH49 highway to the north of Khash, for instance – depict the Taliban’s use of avenues of access, and provide a more complete picture of a district consistently overrun by Taliban forces.

However, not all areas with high Taliban presence are reported on more thoroughly by VOJ. Below, two maps show the number of events reported per province by non-VOJ (left) and VOJ (right) sources. While relative levels of activity appear similar across the maps, several key disparities point to the differences in coverage between these sources. Notably, non-VOJ sources report a much higher concentration of events in Urozgan than VOJ (see left-hand map). Although Urozgan has a strong Taliban presence, VOJ sourcing adds little to ACLED’s coverage of the area. In Urozgan, a large number of the events reported from sources outside of VOJ are airstrikes against the Taliban. These are the type of events that non-Taliban sources have incentive in over-reporting – to depict the Taliban as on the defensive or weakening. This helps point to how supplementing coverage to include information from the Taliban helps to provide a more nuanced view of conflict on the ground.

Conclusion

The inclusion of information reported by the Taliban in VOJ increases both the scope and the quality of ACLED data on Afghanistan. VOJ coverage more than doubles the number of political violence events in ACLED’s Afghanistan dataset, and often provides nuanced insight, more specific location details, and updated information, especially around the Taliban’s strategic objectives, use of resources, and lines of effort. Information from the Taliban also ensures the addition of events which took place in ‘the places in between’ – small skirmishes, attacks on checkpoints, or minor conflicts perhaps not reported by mainstream news outlets. Though these events are largely small, when seen collectively, they present geospatial and temporal patterns which allow analysis into the group’s priorities, as well as their use of infrastructure and space. Furthermore, the addition of VOJ events expands the representation of the conflict: while the Taliban fails to report as robustly as other media in some areas where it is on the defensive or being actively targeted, it reports far more events – small- and large-scale alike – in areas where it is strong. Combining these sources allows increased insight into the ground reality of the conflict.

______

Notes:

[1] Pajhwok notes conflicting reports on battle details from Wardak province, including by state, Taliban, and local reporters.

[2] Afghan Islamic Press reports Taliban claim that it captured the district headquarters of Giro, Ghazni province. State sources respond with a claim that they had earlier moved the district headquarters.

[3] New York Times reports Taliban claim that the group had captured the majority of Farah city, while state representatives reported that those claims were exaggerated.

[4] Pajhwok notes Taliban claim that it had captured Zari district of Balkh amid fighting. State representatives refute claims of capture, however reports from local authorities could not be obtained.

[5] RFERL uses claim of responsibility from Voice of Jihad for a suicide attack on Georgian soldiers in Helmand.

[6] Washington Post reports Taliban claim on fatalities sustained as a result of fighting between the Taliban and the Islamic State (Khorasan Province). Independent reporting on violence between two non-state conflict parties is especially rare.

[7] Long War Journal shows a video taken from the Voice of Jihad website showing Taliban in the aftermath of their takeover of Allahuddin military base in Baghlan-e Markazi district, Baghlan province. Ariana News later confirms the attack.

[8] Information on which actor perpetrated an attack is not coded in ACLED data given systematic bias around this type of information (See the Codebook for more information). When such information is provided by the source, it is included in the “notes” column of ACLED data. Users should understand that because a source reports who the perpetrator of an event might be, it does not mean this is necessarily the case — especially in contexts, like Afghanistan, where the source of such reports are often the conflict parties themselves. Information about alleged perpetration here comes from an analysis of source reporting.