On 29 February 2020, the United States and the Taliban signed a peace deal in Doha, Qatar, after more than 18 years of conflict. The agreement contained four main provisions (US Department of State, 29 February 2020):

1) Halt attacks against the US: The Taliban provided guarantees that it “will prevent the use of the soil of Afghanistan by any group or individual against the security of the United States and its allies.”

2) Withdrawal of US troops: The US agreed to “the withdrawal of all foreign forces from Afghanistan,” stipulating that in the first 135 days, the number of US personnel will be reduced from approximately 13,000 to 8,600. “With the commitment and action on the obligations” of the Taliban, all remaining forces are to be withdrawn by the end of April 2021.

3) Prisoner swap: The US additionally committed “to start immediately to work with all relevant sides on a plan” for the release of up to 5,000 Taliban and 1,000 government prisoners by 10 March 2020 as a confidence-building measure.

4) Intra-Afghan peace talks: The Taliban, which throughout the negotiating process with the US rejected direct talks with the Afghan government, agreed to start intra-Afghan negotiations on 10 March 2020.1 There is however no requirement for a peace settlement.

The publicly released agreement does not contain any provision for the Taliban to reduce attacks against Afghan government forces, and the annexes to the agreement that outline implementation of the deal are classified. However, a spokesman for the US military command in Afghanistan indicated a de facto fifth provision in a recent statement (Military Times, 6 May 2020):

5) Reduction of violence: All sides had made a “spoken commitment” to reduce violence by 80%.

More than 10 weeks on, this report assesses the implementation of these five key tenets in the US-Taliban peace deal. Whereas the US and the Taliban have fulfilled their mutual commitments towards each other, the intra-Afghan prisoner swap, peace talks, and reduction in violence have been marred by delays and setbacks.

1. Halt attacks against the US

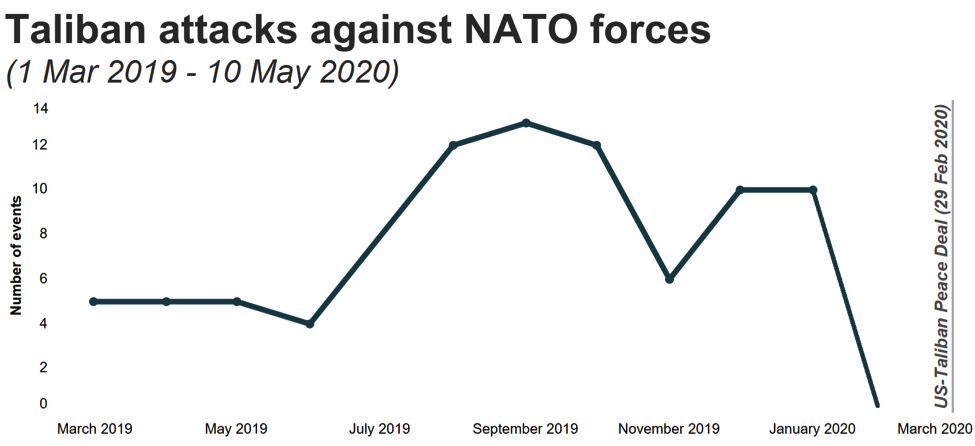

According to US Defense Secretary Mark Esper, the Taliban has not attacked US-led coalition forces in Afghanistan since the signing of the peace deal (VOA, 4 May 2020). In the 12 months prior to the peace deal being signed, ACLED records nearly 100 one-sided attacks launched by the Taliban against US-led coalition forces in Afghanistan.2 ACLED does not code the perpetrator or victim in violent attacks involving two violent actors. Such information can be quite biased and is largely dependent on the source of the information. Information around the perpetrator of one-sided attacks is less biased — though not coded outright by ACLED. For this analysis, one-sided attacks (i.e. events coded with event type ‘Explosions/Remote violence’) were reviewed and classified accordingly. That said, in reviews of two-sided events in which one side ‘claimed’ to be the instigator, the trends are similar if such data were to have been included: if attacks claimed to have been initiated by the Taliban are taken into consideration, this figure increases to about 160 attacks. Since the agreement, no Taliban attacks on the coalition have been reported (see graph below).3The data used in this visual, and all others in this piece, include data published by ACLED, as well as preliminary data not yet published by ACLED. ACLED is in the process of supplementing its coverage of Afghanistan through coding reports from the Taliban’s Voice of Jihad in Arabic; ACLED already publishes coverage of Voice of Jihad in English. For more, see this recent ACLED analysis piece, as well as ACLED’s methodology primer on coding decisions in its coverage of Afghanistan. This is an indication that Taliban political leadership has the ability to control its ranks. Direct breaches of the agreement by the Taliban will remain unlikely, as it would halt or reverse US troop withdrawal, a long-sought demand of the insurgent group (Brookings, 4 March 2020).

2. Withdrawal of US troops

On 9 March 2020, US military officials announced the start of the first phase of troop withdrawal from Afghanistan (BBC, 9 March 2020). By the end of April, the US reduced its forces to fewer than 10,000, making it likely that the 8,600 goal will be reached ahead of the mid-July deadline (CNN, 30 April 2020). The coronavirus pandemic has likely accelerated the process, with American President Donald Trump reportedly pushing for a quicker withdrawal due to concerns over the health of US personnel stationed in Afghanistan (NBC, 27 April 2020). Ahead of the 2020 presidential election, Trump – who has long advocated for bringing US troops home – can point to the withdrawal from Afghanistan as a foreign policy victory. In the absence of a major attack against US assets or interests by the Taliban or an affiliated group, the process will likely be near completion in the coming months.

3. Prisoner swap

Within 24 hours of the US-Taliban agreement, Afghan President Ashraf Ghani – whose government was not party to the deal – rejected the clause that called for a prisoner swap (Al Jazeera, 1 March 2020). Ghani’s reluctance was unsurprising, given the possibility that Taliban prisoners could return to the battlefield, to target Afghan forces, upon release. Freeing 5,000 Taliban prisoners at once would also deprive the Afghan government of one of its most powerful tools of leverage in any future intra-Afghan negotiations (Brookings, 5 March 2020).

Nevertheless, likely to secure US and other international endorsements for his inauguration (Reuters, 9 March 2020), Ghani issued a decree on 11 March that ordered the release of 1,500 Taliban prisoners in batches of 100 per day. The remaining 3,500 prisoners are to be released once intra-Afghan talks begin, on the condition that the Taliban reduces violence (The Hill, 10 March 2020). Between 8 April and 10 March, the government released approximately 1,000 Taliban detainees, and the Taliban more than 260 prisoners.

However, the government has since halted the process, suggesting that only 105 prisoners released by the Taliban are members of the security forces. Officials say that releases will not resume until the Taliban has freed a total of 200 security personnel (TOLO News, 11 May 2020). In all likelihood, the prisoner exchange will continue to be a slow and contentious process. Concerns have been raised that if large numbers of prisoners on either side die from COVID-19, the process will become even more complicated (Reuters, 21 April 2020).

4. Intra-Afghan Peace Talks

The crucial intra-Afghan talks, set to start on 10 March under the US-Taliban agreement, have been delayed by more than two months at the time of this writing. The major sticking point remains the slow process of the prisoner exchange. Taliban officials initially rejected the phased release of prisoners, claiming that Ghani’s decree contradicted their agreement with the US (Al Jazeera, 11 March 2020), but they have since welcomed the releases (RFE/RL, 5 May 2020). It remains to be seen if the group will agree to proceed with the intra-Afghan talks once the government has released the remaining 500 Taliban prisoners in the first phase. Given that the US-Taliban peace deal sets the Taliban’s engagement in intra-Afghan negotiations as a precondition for the second phase of the coalition troop withdrawal, the insurgent group will likely proceed with the talks in the coming months.

Furthermore, intra-Afghan peace talks were undermined by a power struggle between Ashraf Ghani and his rival Abdullah Abdullah. Both men claimed victory in last year’s presidential election and held competing inauguration ceremonies. Ghani and Abdullah have, in the meantime, reached a power-sharing agreement, ending more than eight months of political uncertainty. While Ghani will stay on as president, Abdullah will lead peace talks with the Taliban. A broad political consensus in Kabul is critical for negotiations with the Taliban, should they get underway, and Abdullah will now have to find a united position among the deeply divided Afghan political factions (Al Jazeera, 18 May 2020).

5. Reduction of violence

Fighting in Afghanistan tends to follow a seasonal pattern. Overall levels of violence have traditionally remained low during the winter months, as Afghanistan’s high mountains and snow impede the movement of armed groups. In contrast, fighting often intensifies in spring and summer. An assessment of the level of violence since the signing of the US-Taliban peace deal is therefore best performed in comparison with the same period last year in order to best identify which changes in violence patterns are a result of recent political changes versus seasonal barriers.

Both the total number of violent events and reported fatalities in Afghanistan decreased by about 15% between 1 March and 10 May 2020 compared to the same time period in 2019. This reduction can be mainly attributed to the lower number of one-sided attacks launched by NATO and Afghan government forces during the 2020 period.

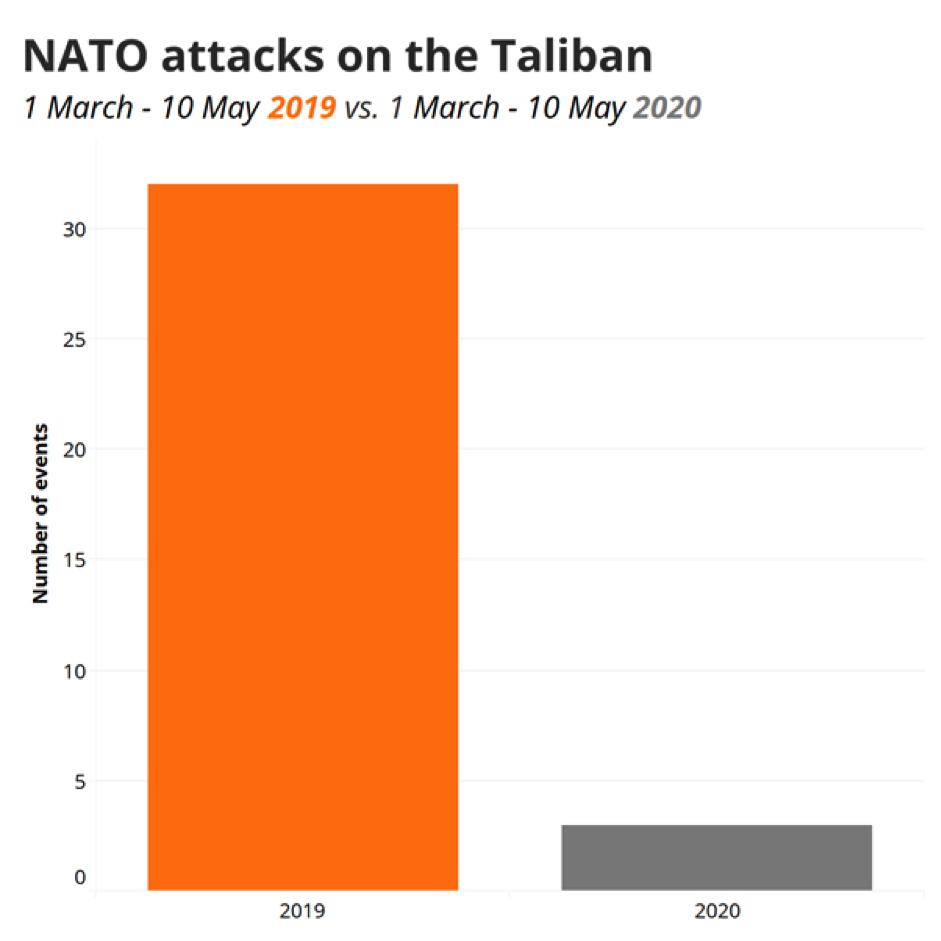

While the US military has recently stopped releasing official information about airstrikes it conducts in Afghanistan (Star and Stripes, 5 May 2020), a spokesman for American forces stated that “the US has not conducted a single offensive strike or operation” in recent months, and has only conducted defensive strikes against the Taliban when they attacked Afghan government forces (USFOR-A, 2 May 2020). ACLED data indicate that the number of airstrikes conducted by NATO on the Taliban has significantly declined since the conclusion of the US-Taliban peace agreement, compared to the same period last year (see graph below).

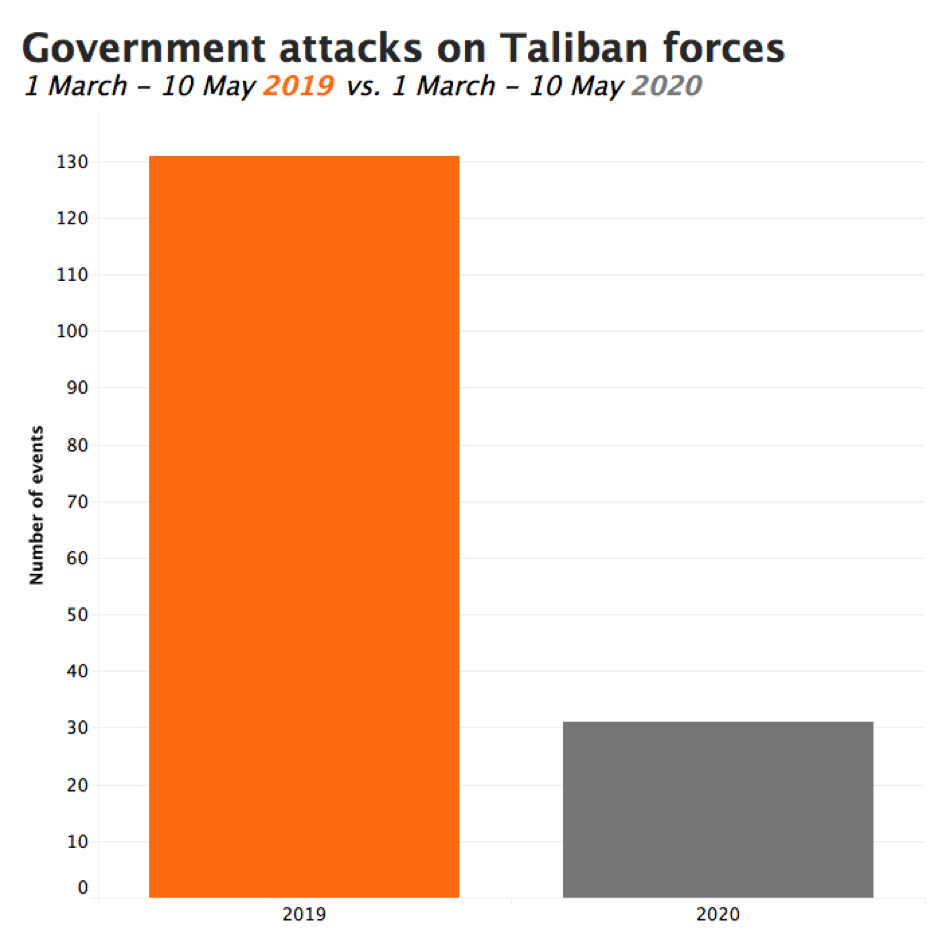

Furthermore, as part of a seven-day partial nationwide ceasefire at the end of February, Afghan forces adopted a defensive posture that continued beyond the reduction in violence period until 12 May. Relative to a comparable 10-week period in 2019, reported one-sided attacks launched by government forces against the Taliban decreased by more than 70% (see graph below). The Afghan government likely hoped that easing off the offensive would convince the insurgent group to proceed with the intra-Afghan peace talks.

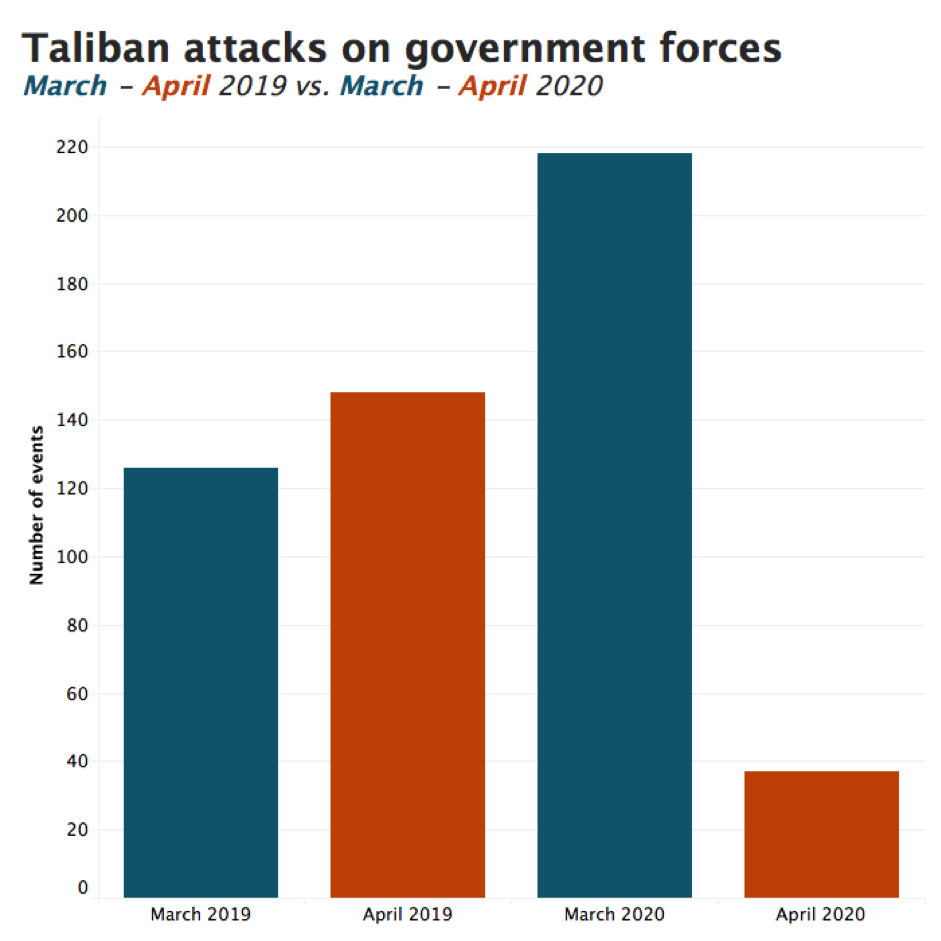

However, as soon as the seven-day reduction in violence was over, the Taliban resumed attacks on Afghan security forces. The latest report by the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR) indicates that the NATO Resolute Support (RS) has restricted the public release of data on enemy-initiated attacks. RS told SIGAR, however, that between 1 and 31 March, the “attacks against [the Afghan National Defense and Security Forces] [increased] to levels above seasonal norms” (SIGAR, 30 April 2020). ACLED data confirm this trend: compared to March 2019, one-sided Taliban attacks on government forces increased by more than 70% during this period.

Still, Taliban attacks declined significantly in April and over the first 10 days of May. Compared to the same period last year, one-sided attacks on government forces decreased by more than half. Notably, the Taliban has neither launched, nor announced, its annual spring offensive as of this writing. This delay was interpreted by some as a nod to the peace deal (The Interpreter, 27 April 2020), though others suggested that it is an attempt by the Taliban to improve its image amid the coronavirus pandemic (Al Jazeera, 14 May 2020).

Levels of violence in Afghanistan may soon increase again. Following two deadly attacks on 11 May, which together resulted in more than 55 reported civilian fatalities, President Ghani ordered Afghan forces to switch to an offensive mode against the Taliban and other armed groups. This shift comes despite Taliban condemnation of the attacks and American assertions that they were carried out by Islamic State militants, as the Afghan government insists that the Taliban and the affiliated Haqqani Network are responsible (Reuters, 15 May 2020). Some suggest that the attacks gave the Afghan leadership the “cover” it needed “to defy the Americans,” as the US-Taliban deal is perceived as a “sellout” by many in Afghanistan (Reuters, 14 May 2020). Depending on how aggressive Afghan security forces become, and whether the Taliban decides to respond in kind, a spike in violence may now precede any potential intra-Afghan peace talks.

Conclusion

Recent developments in Afghanistan show a mixed picture. On the one hand, two main pillars of the US-Taliban peace deal — the end of Taliban attacks on US assets and interests, and the withdrawal of foreign troops — have so far been implemented without any major issue. Yet, on the other hand, attempts to implement the remaining tenets involving the Taliban and the Afghan government have been far more arduous. As expected, the situation between the Afghan warring sides has been much more complicated. There has been some progress in the prisoner release process, but disagreements persist over the number of prisoners to be freed. As a result, intra-Afghan peace talks have been significantly delayed. The Taliban has also given little indication that it will reduce overall levels of violence by 80%.

Ultimately, recent developments have shown that while the US-Taliban agreement will likely succeed in bringing an end to American military involvement in the Afghan war, peace in Afghanistan remains elusive.