This is the first in a series of three analysis features covering unrest in Sudan, and the repercussions of this unrest for the wider region. Sudan is grappling with the legacies of decades of violence and quasi-military rule under the deposed President Omar al-Bashir, which has disproportionately affected marginalized areas of the country. This first piece explores recent patterns and trends in violence in such areas, focusing in particular on insecurity in Darfur and the “Two Areas” following the coup that ousted Bashir in April 2019, as a number of rebel groups prepare to sign peace agreements with the government. The second piece moves from the margins to the center, and analyzes unrest and political developments in the heartland of political power in the central areas of Sudan. In addition to assessing protest dynamics and suppression, the piece considers the implications of the arrival of paramilitary factions from Sudan’s semi-periphery of Arab-identified groups in the crucible of power in the country, notably the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) paramilitary group under the leadership of Lt. Gen Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo (a.k.a ‘Hemedti’). The final piece pans further back to situate these developments in Sudan within the Horn of Africa, and considers the effects of involvement by external powers, and in particular from the Gulf states.

After a tumultuous 18 months, Sudan is on the edge of another reorganization of power. Rebel groups from the marginalized regions of Darfur and the “Two Areas” of Blue Nile and South Kordofan are preparing to enter the transitional power-sharing government. They will join the ranks of military and paramilitary elites, operating alongside a fractious civilian coalition, who are governing an increasingly unstable country. The interaction between the military establishment, paramilitary elites from Sudan’s semi-periphery, and rebel elites from the periphery will have a decisive influence on the outcome of Sudan’s revolution, though perhaps not in the way that protesters who led the uprising would have hoped for.

Although often presented as a “transition” from military authoritarianism to civilian democracy, this historical moment is better understood as a reckoning for Sudan, in which elites from the core, the periphery, and the semi-periphery reorient themselves around the wreckage of a state that has long relied on pitting the population against one another in order to maintain its rule. The outcome of this reckoning is uncertain, and complicated by a multiplicity of vested interests, rebel groups, and paramilitary factions, with consequences for the Horn of Africa and potentially beyond.

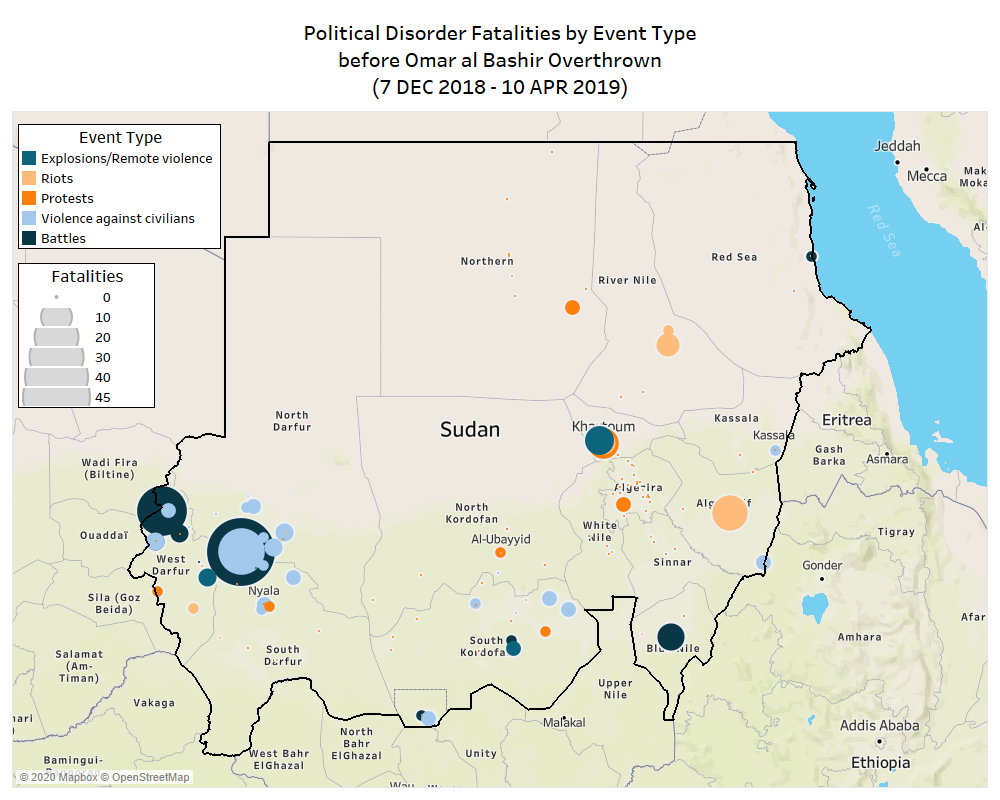

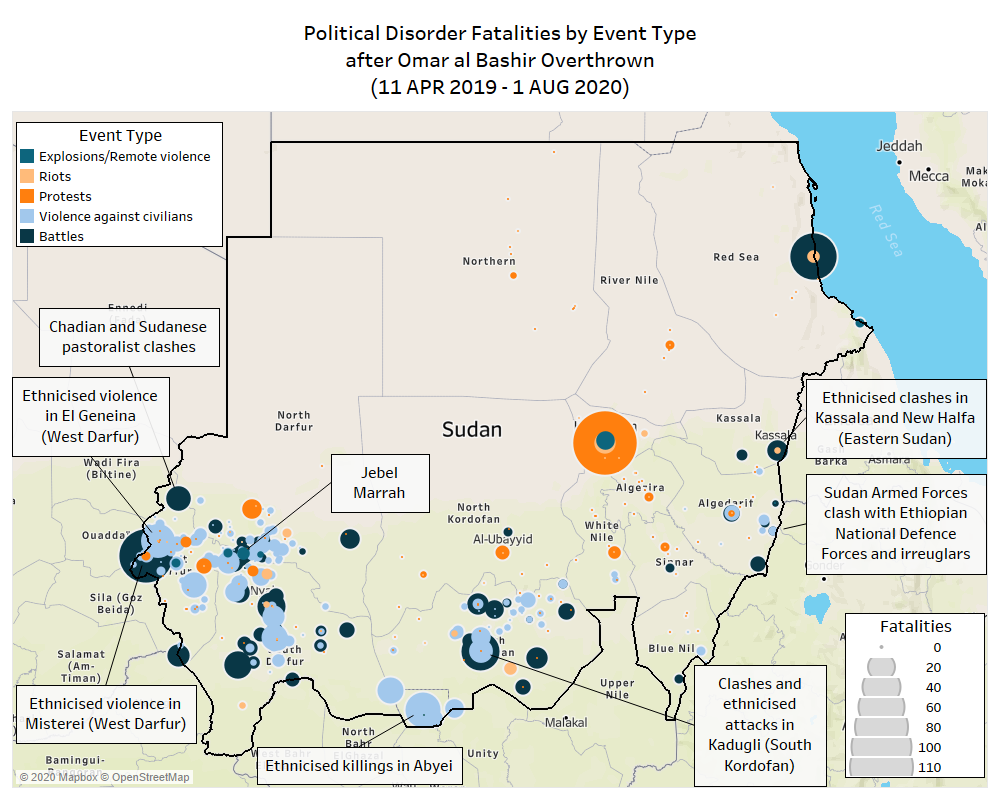

Despite recent fighting along the Ethiopian border and clashes in Kassala and Red Sea states to the north-east, battles and violence against civilian events continue to be concentrated in Sudan’s southern and western peripheries. With the exception of intense violence in Khartoum on 3 July 2019 and in Port Sudan in late August 2019, events in Darfur and South Kordofan also continue to be the most lethal in Sudan (see maps below).

However, the character and dynamics of that violence has shifted to the extent that current peace negotiations will have little effect on levels of violence, other than to potentially raise them. The first part of this analysis outlines patterns of violence in Sudan’s margins since Bashir was overthrown, noting how violence has become increasingly concentrated and urbanized, pitting (mostly) irregular forces from marginalized non-Arab groups against irregular and paramilitary forces of the semi-periphery. Such violence may be increasing as a result of fear and competition between the periphery and the semi-periphery as they seek to establish their place in the politico-military order being forged in Khartoum.

The second part unpacks the trajectories of Sudan’s various rebel groups, noting the decline of all rebel movements who are engaged in serious and sustained negotiations with the government, and the relative strength of those either tangentially engaged in the peace process, or refusing to participate. The weakness and desperation of most rebel groups currently precludes their involvement in the deadly contests described in the first section, meaning that the peace process is unlikely to resolve such violence. However, were these rebel groups to be emboldened by the peace process, then an intensification of urbanized clashes cannot be ruled out, as could violence relating to rebel integration into security structures.

In the final part of this analysis, the functions of the peace process and the motivations of its mediators are considered, establishing that the process is an essentially conservative reordering of power designed to uphold a system already dominated by Sudan’s various security organs. Given that most peripheral rebel groups exhibit characteristics which are not compatible with the ideals of democracy and equality that animated protests in December 2018, but which are instead complementary to the goals and behavior of Sudan’s military establishment and new paramilitary elite, there are good reasons to be cautious about the type of peace the agreements will attempt to embed. Current signs suggest that a reactionary rather than revolutionary peace is the most likely outcome of this process.

A Darker Dawn: Violence After the Uprising

Contrary to the popular narrative, the demonstrations which ultimately fed into the removal of President Bashir and the ruling National Congress Party (NCP) began not in the northern city of Atbara on 19 December 2018, but on 7 December in the small town of Mairno in Sennar state (Radio Dabanga, 8 December 2018) and later in the city of Ed Damazin in the peripheral area of Blue Nile state (Radio Dabanga, 14 December 2018). The lifting of subsidies on bread and fuel catalyzed unrest in the peripheries, which then spread northwards to the capital of Khartoum and onwards to Atbara, where the Sudanese Professionals Association (SPA) labor movement took a leading role in organizing anti-NCP demonstrations.

Despite the origins of the uprising arguably beginning in the geographical and political margins of Sudan, and continued sacrifices being made by demonstrators from this periphery (Radio Dabanga, 12 April 2019), the composition of Sudan’s power-sharing bodies in Khartoum is not representative of Sudan’s marginalized groups. Further, the presence of both Sovereign Council Chairman General Abdul Fattah al-Burhan and Deputy Chairman ‘Hemedti’ at the apex of power is particularly unsettling when viewed from the margins, given their direct links to groups involved in producing the humanitarian cataclysm in Darfur in 2003. The civil war in Darfur formed a platform for the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) commander Hemedti to accrue considerable wealth and power in Darfur, South Kordofan, which would come to be projected into Khartoum. Hemedti himself comes from the semi-periphery of Arab-identifying pastoralists groups, who’s declining fortunes in the political economy of Sudan have resulted in such groups launching violent attacks against weaker non-Arab groups in Sudan’s frontiers. Such attacks have often been masterminded by elites in Khartoum, with irregular militia groups being armed and organized into an assortment of paramilitary groups.

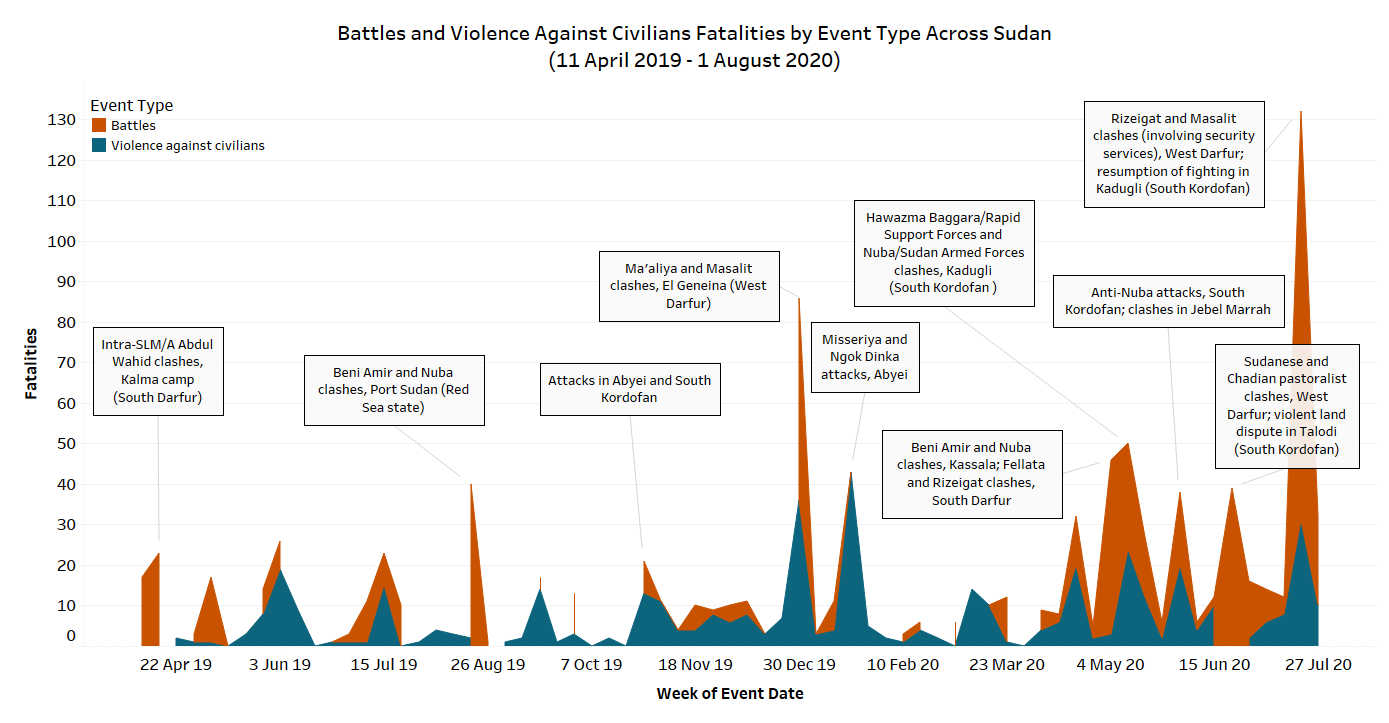

Levels of violence against civilians and battles have been increasing gradually since Bashir was overthrown in 2019, with a rise in fatalities. This represents a somewhat partial reversal of the markedly declining number of violent events since 2016 as clashes involving rebels substantially fell. However, fatalities are far below the last bout of serious insurgency activity that followed the secession of South Sudan in 2011, and which was snuffed out by a sustained counterinsurgency campaign from 2014-2016.

Since the fall of the NCP regime in April 2019, small-scale incidents of violence against civilians have remained a common occurrence in parts of South, North and Central Darfur states as well as South Kordofan, and increasingly in West Kordofan (see maps above). Such acts are mostly carried out by pastoralist groups against civilians, often targeting internally displaced persons (IDPs), whilst Popular Defence Forces paramilitaries (an Islamist paramilitary force established in the early 1990s, and officially dismantled this year) have been implicated in a spate of attacks in South Kordofan. Attacks against IDP farmers have tended to increase as IDPs return to their land, with a particularly deadly event occurring in Gerieda locality of South Darfur on 23 July when an unknown militia group killed almost 20 returnees. Recurrent attacks and abuses in Central Darfur prompted the establishment of sit-in camps in Nertiti, Kutum and Fata Borno over the past months, which aim to pressure the state into disarming the irregular militias, many of whom are drawn from the semi-periphery and have enjoyed tacit or explicit support from Khartoum.

There has been a change in the type of actors involved in the clashes, with a move away from rebel groups toward irregular militias and paramilitary forces. This shift has been underway over the past decade and has accelerated in pace since the fall of Bashir. However, the principal shift has been in the geography of the conflict, with serious violence increasingly taking place in and around towns and cities. This contrasts to the predominantly rural fighting of the past, and is now taking a more explicitly ethnic form. In some cases, notably in Kadugli (South Kordofan) and El Geneina (West Darfur), members of the security organs have been actively involved in the fighting, splitting along ethnic lines.

The primary reason such violence now involves more urban flare-ups is because systematic displacement resulting from attacks by government and pro-government forces over several decades has forced large numbers of non-Arab groups into large IDP camps near urban centres. Some of these adjoin major towns and cities, notably in El Geneina. The reasons why violence proceeds along ethnic lines is due to the government’s and the Sudan Armed Forces’ historic preference to outsource violence in the peripheries to paramilitary groups from specific ethnic groups of the semi-periphery (Small Arms Survey, 2017). The government became increasingly dependent on turning parts of the semi-periphery of impoverished Arab-identified pastoralist groups such as the Rizeigat or Baggara against the poorer and weaker non-Arab groups across large parts of Darfur, Blue Nile, South Kordofan and Abyei. This served to transfer both risks and responsibility for violence to semi-peripheral groups, and encouraged a misdirection of grievances by such groups away from the government and towards those who were not responsible for their declining fortunes. It has also created zero-sum contests between peripheral and semi-peripheral groups over land and resources in already tense areas ( Craze, 2013).

In the post-Bashir era, these factors have combined to create a set of tinderboxes scattered across peripheral towns and cities, which are sparked when the dominant, state-aligned group feels their power or access to resources is threatened by a dispossessed group reasserting its claims on territory, resources or formal representation. The violence is often better understood as being ethnicized resource disputes and viscous attempts at asserting group security — often driven by national-level changes and fears around the outcome of the ongoing peace process — rather than being “ethnic conflicts” per se.

The tempo of the violence is shuddering, with a brief burst of intensive violence preceded and followed by smaller violent incidents (see figure below). Although the specific instances of violence vary in their form, many follow ethnic contours which had been sharpened in the previous decades of NCP rule. An increasing number of events involving violence being initiated by members of the peripheral group (such as the Nuba, Masalit or Ngok Dinka) who are often subject to abuses by the more dominant, government-aligned group of the semi-periphery (including Baggara and Rizeigat pastoralists), as has happened in the run-up to episodes of mass violence in Abyei in January of this year and El Geniena in West Darfur in late December 2019. This has tended to be followed by disproportionate reprisal attacks from the dominant group, often leading to dozens of deaths in lopsided fighting or massacres. Such fighting has typically followed along ethnic lines, specifically pitting members of the periphery against the recently dominant semi-periphery, becoming particularly serious when security forces get involved. For example, this pattern is evident in violent events involving marginalized Nuba against Beni Amir in Port Sudan and urban areas of Kassala state in eastern Sudan; Rizeigat Arab-identified pastoralists clashing with ethnic Masalit in West Darfur; Arab-identified Baggara of the Hawazmah clan against ethnic Nuba in the Kadugli area of South Kordofan; and with Ngok Dinka against Arab-identified Misseriya in Abyei.

Similar instances of reprisal attacks have occurred in Bielel locality of South Darfur on 9 March which killed 13, and again in the town of Tamur Jamil in north-east Zalingei locality in Central Darfur, in which large parts of the town were torched and 2 people killed on April 21. West Darfur in particular has been a recurrent site of this dynamic. Following intense clashes and attacks in late December around El Geneina, violence continued into late March with clashes pitting ethnic Masalit against an Arab-identified group in West Darfur in the Jebel Silk area, resulting in the deaths of 8 persons. Reprisal attacks and vigilante killings have, in recent weeks, led to serious fighting in El Geneina and Misterei, where at least 77 people were reportedly killed on 25 July during a Rizeigat attack against Masalit (Darfur 24, 2020). This violence has also drawn in members of the security services. Such fighting is particularly concerning when RSF and regular army forces engage one another, which has occurred in and around Kadugli, whilst the presence of uniformed personnel has been reported in several major clashes in West Darfur (and will be discussed in greater detail in the second analysis piece).

Cumulatively, these shifts reflect how flashpoints have converged around urban areas, and are driven –at least in part– by mounting anxieties about the losers and beneficiaries of the upheaval in Sudan, which are typically refracted through ethnic lenses. These are the byproducts of decades of war and manipulation emanating from the core of the country. If left unaddressed, these may escalate as military and paramilitary forces are sucked in to the conflicts. As will be discussed below, it is doubtful that the current peace process will have much effect on resolving (let alone containing) such violence, given that they primarily focus on integrating rebel groups into the transitional government. This focus suggests the peace process is concerned less with reducing violence and overhauling oppressive structures than it is on establishing the terms in which peripheral rebel groups coexist with semi-peripheral paramilitaries and military forces from the central region of the country.

Missing in Action? The Rebels of Darfur and the Two Areas

Absent from much of the above described violence are those rebel groups that are currently in talks with the government, as well as the Sudan Liberation Movement/Army (SLM/A) group of Abdul Wahid al-Nur, who are not participating in the talks. The number of rebel groups and splinter factions has declined significantly since the height of the violence in Darfur in the mid-2000’s, and has been whittled down to the remnants of the Justice and Equality Movement; two factions of the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement – North; and the two separate SLM/A rebel groups under the respective control of Abdul Wahid and Minni Minawi, with a number of offshoot groups and splinter factions surrounding the Abdul Wahid group.

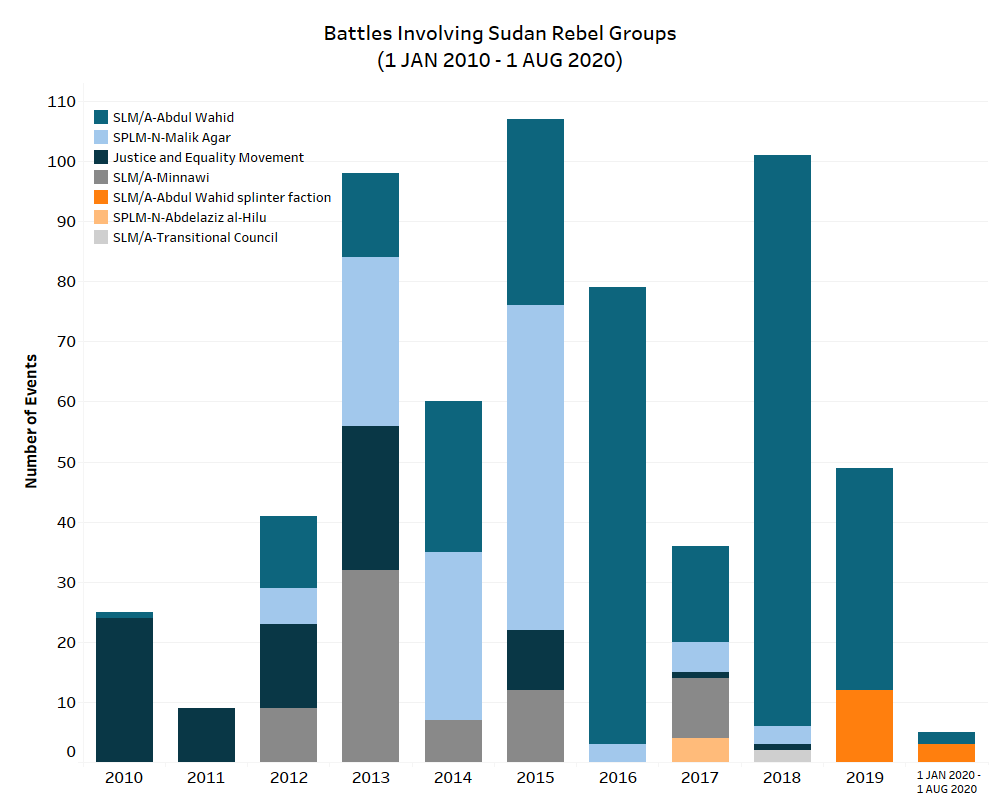

Most of these rebellions have been dormant for several years,in part because they have long-standing ceasefire arrangements with government forces from before the uprising of December 2018, whilst the SLM/A under Abdul Wahid adopted a “de facto ceasefire” after the fall of Bashir (UN, 2020). The ceasefires represent a step towards formalizing a negative peace (i.e. the absence of hostilities, but retaining conditions which could lead to future conflict) in remote areas, which have seen decreasing levels of activity involving rebel groups for several years, with the exceptions of hotspots around Jebel Marrah in central Darfur involving SLM/A Abdul Wahid fighters (see figure below). The long-term decline in rebel activity also speaks to relatively successful efforts at co-option and counterinsurgency on the part of the Bashir regime, alongside more positive relations between Khartoum and neighboring countries who have typically provided support to Sudan’s rebels. It also reflects diminished internal capacity within the rebel groups, and speaks to the legacies of damaging leadership disputes which have blunted their influence.

The ongoing peace talks are aimed at further embedding and stabilizing the status-quo. Since the collapse of the NCP, a remarkable level of diplomatic activity aimed at integrating armed and unarmed opposition groups into the new political order has been initiated. This has taken the form of a series of peace agreements for different regions of the country, and where there are multiple rebel groups based in these regions, bilateral negotiations between the rebel leadership and the government. The agreements are being negotiated in Juba, South Sudan, mediated by the South Sudanese political elites Tut Kew Gatluak and Dhieu Mathok, both of whom have strong historical links with the now-outlawed NCP and the Sudanese security establishment, particularly Tut.

The level of information about the various peace agreements (with specific agreements referred to as ‘tracks’ or ‘files’) being signed varies, and it is difficult to tell whether these different agreements will ultimately cohere with one another when the final comprehensive agreement is signed. The peace process has itself been postponed on several occasions following violent incidents, such as attacks and harassment by RSF and ethnic Hawazmah militia against civilians in the Khor Waral area of South Kordofan in mid-October 2019 and the intense violence in and around El Geneina beginning late December 2019. More recently, an attack by unknown militiamen on the sit-in at Fata Borno IDP camp caused a further postponement of the talks. Despite these frequent postponements, it should be remembered that these rebel groups are in no way involved in much of this violence, and that the peace process will likely do little to address these violent incidents.The postponements are better understood as a stalling tactic to enhance negotiation positions.

The question is thus: Who are the groups being brought in the fold under the Juba peace talks, and is their involvement likely to have an effect on the contours or intensity of violence in the peripheries outlined above?

The Sudan People’s Liberation Movement – North (SPLM-N) comprise rebels mainly drawn from Blue Nile and South Kordofan states along the border with South Sudan, who fought alongside southern rebels during the Second Sudanese Civil War (1983-2005), but were left marooned in the north as a result of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement of 2005, which paved the way for South Sudanese independence in 2011. The secession of the South led to renewed government assaults on SPLM-N rebels, culminating in an intense counterinsurgency campaign from 2014-16, which reduced the SPLM-N’s area of operations, particularly in Blue Nile. The movement then fractured in 2017 when leadership tensions between Abdelaziz al-Hilu and the long-standing leaders Malik Agar and Yasir Arman boiled over, amid general dissatisfaction with the performance and direction of the rebellion under Malik Agar (Young, 2018). Barring serious clashes between the two factions of the SPLM-North in Blue Nile state in February 2018 that killed dozens, the only other event in the past two years involving the SPLM-N took place in December 2018 in Blue Nile, when members of the Malik Agar faction clashed with government forces and paramilitaries resulting in 7 deaths.

Despite their more limited activity, the faction of Abdelaziz al-Hilu is the militarily dominant bloc of the group, and has been more assertive compared to the Malik Agar faction with regards to the issue of self-determination for the Two Areas. The Abdelaziz al-Hilu faction is also the only rebel group involved in negotiations with the government that controls any substantial area of territory, and as such has been more effective in negotiations. However, the Abdelaziz al-Hilu faction announced in the past week that it was withdrawing from peace talks on the eve of the proposed signing ceremony (scheduled for 28 August), in protest at the dominance of Hemedti in the peace talks, and a flare-up in violence in the Khor Warral area of South Kordofan (Radio Dabanga, 21 August 2020), which is on the outskirts of the faction’s Nuba Mountains heartland. Although there is (perhaps deliberate) ambiguity regarding the permanence of the withdrawal, this is a troubling development for the mediators, who now face the prospect of a relatively strong rebel group – one that has recently aligned with the SPA that spearheaded anti-Bashir demonstrations – undermining the credibility of the peace deal at the eleventh hour.

Among the groups present at the start of the crisis in Darfur in 2003, there is again very limited activity. A faction of the Justice and Equality Movement (JEM) fought against RSF paramilitaries on the South Sudan border in January 2018, resulting in three deaths. There has been no other activity from the remainder of JEM (who have been largely serving as bodyguards for an unpopular former governor of Western Bahr el Ghazal state in South Sudan), and none whatsoever from the Minni Minawi SLM/A group in recent years. Neither of these rebel movements – whose leadership hail from the Zaghawa ethnic group – have a permanent presence in Darfur due to extensive government counterinsurgency efforts across 2014-2016. The groups have been permanently dislodged to South Sudan and Libya, and with greatly reduced numbers compared to their heyday. There are under 1,000 JEM fighters in Libya and a far smaller number in South Sudan, whilst there are fewer than 200 SLM/A Minni Minawi fighters in Libya (Young, 2020, p.22; UNSC, 29 June 2020; UN Panel of Experts, 2019, pp.21-23 ). In late April of 2018, the tiny Transitional Council splinter faction of the SLM/A Abdul Wahid group claimed that it had repulsed an attack by the army, although there are no reports on fatalities.

Group activity is not the only indicator of a group’s level of capacity, but the inactivity of the principle armed groups involved in the peace is striking. If all goes as planned with the peace talks, then the absorption of these groups into the regular forces may help to render the lengthy ceasefire permanent and prevent a relapse into cycles of insurgency and vicious counterinsurgency which have long haunted the peripheries. However, the peace process should not be expected to result in a pronounced reduction in violence or clashes, given the extremely low level of activity of most rebel movements and their almost complete lack of involvement in urbanized and ethnicized fighting discussed earlier. It should also be emphasized that Sudanese rebel groups do not constitute a united front, with historical rivalries between groups and internal factionalism within them. Coalitions of rebel groups have also suffered from leadership disputes and splits, notably with the Sudan Revolutionary Front which has split, reformed, and then partially split again this May (Radio Dabanga, 21 May 2020). This makes the individual groups prone to external manipulation as well as mutual suspicion. Meanwhile, certain smaller groups – some of whom have no combat record at all – have been bundling themselves together with larger ones (Radio Dabanga, 6 August 2019), presumably to attach themselves to peace negotiations and secure jobs resulting from these talks.

The main rebel group involved in somewhat regular clashes – the SLM/A under Abdul Wahid – is not a part of the peace process. Conflict between rebels from this largely ethnic Fur holdout group and government forces has continued in the Jebel Marrah area, which is under the control of the various sub-factions of the group. Since October 2019, the fighting has been internal to the group and its numerous sub-factions, with the possible exception of clashes with government forces in early June 2020.1 SLM/A Abdul Wahid rebel clashes are disputed by the rebel group itself. They have not been included in the bar graph below. Fighting among the myriad commanders of the rebellion has often resulted in civilian casualties and displacement, and has been driven by leadership disputes, political disagreements relating to participation in peace processes, and competition over recently discovered gold deposits in Jebel Marrah. Some of the increased revenues from the gold deposits have been put towards obtaining new weapons (UN Panel of Experts, 2020; UNSC, 2019; UNSC, 12 March 2020; IOM, 2020).

The group’s organisational structure has deteriorated into a complex arrangement involving Abdul Wahid (based in Paris) issuing instructions to his loyalist commanders (based mainly in Jebel Marrah), often bypassing his formal military command structure to issue orders directly to preferred commanders. These loyalists exist in close proximity to a set of autonomous commanders in and around Jebel Marrah. Loyal and autonomous commanders are at times aligned to achieve tactical goals, and at others violently compete for resources with one another. These are circled by an array of dissident commanders, mostly aligned to the government, who are engaged in periodic clashes with both loyal and autonomous factions. These clashes have tended to escalate and the structure of the group thrown into flux whenever elements of the group engage in peace talks with the Sudanese state (more information on these factions can be found in the Appendix below).

Despite this debilitating fragmentation, the Abdul Wahid faction remains the only active rebel group in Darfur. However, much of the group’s energy is consumed by its business interests and collecting taxes from IDPs in camps aligned to the group, with most business activity now centered in South Sudan. Bringing the group into peace negotiations raises two immediate concerns. First, given that previous peace negotiations with the government have tended to drive rounds of violent factionalism in the group, an increase in violence in Jebel Marrah is the likely outcome, at least in the short term. Second, integrating such a convoluted and unstable structure into the regular army, or even attempting to relocate parts of this network outside of Jebel Marrah, will most probably lead to increased predation on civilians and feuds over resources, and risks drawing elements of the rebel group into the increasingly intense and ethnicized violence in Darfur which it has thus far stayed out of.

Given the limited role of many rebel groups from Darfur and the Two Areas in violent events in these areas, and the difficulties in engaging the only two groups with any substantial degree of territorial control (the SLM/A Abdul Wahid and SPLM-N Abdelaziz al-Hilu factions) in peace talks, it is reasonable to conclude the peace process will have little direct role in reducing violence Sudan’s peripheries. What, then, is the function of the peace talks?

The Re-making of a Military State

The fall of the Bashir regime provided an opening for a renegotiation of power in Sudan, which was swiftly seized upon by the government of South Sudan. The government in Juba hoped to maintain stability and military rule in Sudan, and consolidate improved relations between Sudan, South Sudan and Uganda. This was to allow war-ravaged South Sudan to avoid being dragged into border conflicts, proxy wars, and economic brinkmanship with Sudan in the event of a chaotic transition in Khartoum, which would reverse the gains made by South Sudanese authorities in their own civil war and unravel the current peace agreement in the South.

Thus far, the peace agreements in Sudan appear intended to safeguard the current order in Khartoum through incorporating peripheral rebel movements, whilst ceding some formal power to these groups and the areas they hail from. The comprehensive scope of the talks represents a positive change from Khartoum’s historical preference to negotiate with individual rebel groups (or commanders of rebel factions) one at a time, whilst leaving the oppressive structures of power in Sudan intact and able to refocus efforts at continuing counterinsurgency campaigns in areas not party to peace negotiations. Moreover, the dismantling of the notorious National Intelligence and Security Services (NISS) in July 2019 has limited the ability for security services to manipulate rivalries within rebel groups to the government’s advantage, and spared rebel-occupied areas the fallout of rebel infighting. Assuming the government and security organs adopt a relatively coherent posture with regards to the peace process, then the agreements they strike will be predicated on ensuring that more constituencies in Sudan – particularly rebel groups – are invested in the survival and stability of the regime.

At its heart, the Juba-mediated peace process is conservative and intended to generate political stability in Khartoum, for the benefit of governments in the wider region. The agreements are not intended to accelerate a transition to civilian or democratic rule, which would be inimical to the interests of authoritarian governments in countries surrounding Sudan. The agreements are instead being negotiated between rebel, military, and paramilitary elites, and in the deeply militarized environment of South Sudan. Although the final agreements are due to be signed imminently, public information on the specifics of the various files is obscure. The secrecy may be intended to limit the possibility of groups re-opening of negotiations in the event their peers secure a deal on more preferable terms, though is typical of agreements among military actors.

Available information indicates that the contours of the agreement address terms of incorporating rebel groups into the current system, accompanied by (often broad) pledges to address highly contentious issues surrounding land. The recent suspension of peace talks by the Abdelaziz al-Hilu faction of the SPLM-N means that any potential agreement with this faction will not be ready alongside the others. This is significant, as Abdelaziz al-Hilu and his new allies in the SPA will agitate for more sweeping and politically progressive reforms of the transitional government than any other rebel group, and push for self-determination for the Nuba mountains (Africa Confidential, 2020). Incorporating his demands and those of his SPA allies would likely result in discord with other rebel groups in negotiation with the government, and represent a challenge to the conservative and military-dominated order being gradually rebuilt in Khartoum.

For the Northern track, which covers an area without rebel forces, the agreement is concerned with addressing grievances caused by the Bashir regime’s heavy-handed rule. Provisions include administrative changes as well as new spending commitments, which are joined with reforms to environmental standards and pledges to compensate those displaced by the Merowe dam (Radio Dabanga, 27 January 2020). The inclusion of this track is curious given the lack of rebel movements, and the historically low levels of violence in the northern core of the country (with the exception of periodic massacres by state forces against demonstrators). It does however provide the process with a sense of geographical comprehensiveness, and disburses positions and resources to interest groups from the area.

In war-torn areas of the peripheries, more complex agreements formalizing the role of rebel groups in official political and security structures have been advanced. These agreements include provisions addressing other issues such as determining the administrative status of an area in relation to the central government in Khartoum, the distribution of positions and money alongside amnesty for past crimes, as well as a set of contentious issues such as land use and rights of return for the displaced in Darfur (Radio Dabanga, 24 April 2020). These agreements will almost certainly be constructed in such a way as to safeguard the economic resources of military and paramilitary elites, with Hemedti taking a particular interest in certain negotiations (Radio Dabanga, 26 January 2020).

The current information on the Eastern track agreements is again vague, though seems to be a hybrid of the above agreements (Radio Dabanga, February 28 2020). These talks have also re-started earlier this month, indicating that certain interest groups were unsatisfied with the arrangements made, with some accusations that the agreement is little more than a rehash of an earlier, largely unimplemented agreement (Radio Dabanga, 6 July 2020). Given the country’s economic situation, the government would not be able to afford much of the content of any of these peace files unless external parties, presumably Gulf states, agree to foot the bill. Were this to happen, such spending would be unlikely to significantly rebalance the highly unequal distribution of wealth and capital in the country.

Externally-mediated peace talks are joined with a series of internal peace agreements to control ethnic strife, again with an active role from Hemedti (Al Rakoba, 2020). Such agreements have tended to follow ethnicized violence described in the first section above. Although the durability of these arrangements is somewhat doubtful given frequent relapses into violence in Port Sudan (an epicentre of Nuba and Beni Amir violence, and the site of several peace interventions; see Radio Dabanga, 13 December 2019), these agreements have not received the same degree of attention as the Juba peace talks. However, they may be of significant importance for tracing internal restructurings of power relations, and for setting the terms within which the periphery and semi-periphery are expected to interact with one another in densely populated and ethnically tense areas.

How will the balance of power in Khartoum be affected by the arrival of these rebel groups? It should not be assumed that integration of rebel forces into the transitional political and military structures necessarily strengthens the Forces for Freedom and Change (a coalition of trade unions, activist groups and political parties, discussed further in the forthcoming second analysis) or civilian and progressive politics more generally, even if it will place some limitations upon the military. To do so would be to misrepresent the situation in Sudan as a simple struggle between democracy and military authoritarianism, with the different actors arranged on a continuum between civilian and military. Instead, the current moment in Sudan is better understood as the culmination of decades of militarization which runs through the core and into the peripheries of the country, and often outside of the country’s borders. The rebel movements in Sudan are very much a product of this militarism, and connecting these rebellions to power and resources in Khartoum will have unpredictable consequences, which may ultimately strengthen military power and deepen its presence in the peripheries. Indications suggest that paramilitary and military elites are engaged in a competitive process of accumulating assets and capital, rendering civilian politics dependent upon these actors for resources (Gallopin, 2020). Rebel groups may well attempt to do the same, albeit with a greater focus on the periphery and border towns.

The experience of South Sudan provides a cautionary tale. After South Sudan seceded, many external observers seemed reluctant to point out that the new government being built by the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army (SPLM/A) in Juba was starting to look rather like the one they had escaped from in Khartoum. It has become clearer with time that in the run-up to South Sudanese independence in 2011 that the government was purposefully building a security architecture which resembled that of the north, indeed with active cooperation from NISS, the regime police for Bashir and NCP elites (Adeba, 2020). Such a system was created to help prevent coups, and to oversee the many points of weakness in the vast military system, which had been assembled out of an assortment of rebel and paramilitary groups and a deeply factionalized SPLM/A. When civil war broke out in South Sudan in 2013, the lines of fracture broadly mirrored those of the previous civil war.

As with many Southern Sudanese rebel groups, Darfurian rebel groups and SPLM-North factions articulate a set of genuine grievances held by minority groups excluded from national power on the basis of prejudice and their near-irrelevance to the economy of the country. These areas have been brutalized at the hands of the state and its proxies, or else cast further adrift during long stretches of austerity. The rebel groups representing them have not however demonstrated much willingness to transmute the aspirations of the marginalized into markedly improved forms of rule or governing structures, even if their conduct generally exceeds that of Sudan’s notorious paramilitary and regime police forces that kept Bashir in power. Although beginning life as multi-ethnic rebellions, splinter factions have tended to proliferate primarily along ethnic lines in the majority of rebellions, whilst groups have been torn apart by leadership disputes which have collectively set back the goals of peripheral groups against the center. In the case of Darfur, ethnic splits have occurred because smaller ethnic groups fear domination by the larger ethnic group in the rebel movement.These damaging disputes are more commonly linked to personal rather than political motivations, with leaders tending to indulge in egoistical contests for money and power (de Waal, 2015, Ch.5). In other words, they are not so dissimilar to the current ruling elite in Khartoum, and the possibility they would side with the military establishment against progressive forces or protesters should not be discounted, if the rebel leaderships perceive it to be in their interest to do so.

This is a concern given that the peace talks are calibrated towards maintaining stability via accommodation and reform, rather than overhauling the deeply embedded structures which have driven and enabled decades of violence and asset stripping in post-colonial Sudan. At worst, the integration of rebel groups risks introducing further instability into parts of the military system where they are stationed, and, depending on the positions offered to rebel leaders, such instability could creep up to the higher levels. Uneven levels of training and cohesion across the rebel groups and factions, along with the likelihood of skills fade having set in for dormant rebel groups, will complicate any process of military integration. Furthermore, lingering rivalries between different rebel factions and between rebels and paramilitary forces will in the short-term increase insecurity in areas around military camps and garrisons, making these areas a hazard for civilians. Such problems could be compounded were rebels to re-recruit along ethnic lines prior to military integration.

Although details on the security arrangements under the Juba talks have not been disclosed at the time of writing,2SPLM-N Malik Agar forces have agreed to integrate their (very limited) forces into the SAF over a 39-month period, whilst JEM and SLM/A-Minni Minawi factions are attempting to integrate their (also limited) forces over an unnecessarily lengthy time-span of seven years (Sudan Tribune, 23 August 2020). problems could be anticipated in the event rebels are permitted to retain arms and provide security in their areas of operation. This would potentially inflame relations between clashing peripheral and semi-peripheral groups if rebels are involved in security provision (where they would be expected to come down on the side of their ethnic group in the event of ethnicized fighting), and in the event that joint patrols are mandated in the security arrangements that clashes occur within these patrols. Further, without progress towards demilitarizing Sudan’s peripheries and carefully decentralizing power from the core, elite ambitions among and within the different rebel factions may create problems in the event elections occur at the end of the 39-month transitional period, particularly over powerful governorships positions.3Note that elections may be postponed for at least a year as part of the peace process. Although some rebel groups at the Juba talks are reported to have been receptive to some form of Security Sector Reform both internally and at the national level (Berhe and Detzner, 2020, p.19), it remains to be seen whether this understanding of their own past abuses and excesses will extend to a change in the political character and the internal coherence of the rebel groups.

Were it not for the collapse of the Bashir regime, most of Sudan’s rebel groups would have remained largely outside of the country, and likely become involved exclusively in conflict in Sudan’s neighboring states, especially Libya. The two stronger groups – SLM/A Abdul Wahid and SPLM-N Abdelaziz al-Hilu – would have created fiefdoms in Jebel Marrah and the Nuba Mountains. The peace process gives weaker groups a route back to Sudan, but risks emboldening them in the process. Assuming the final set of agreements are signed, these groups will join an unsteady transitional government and Sovereign Council in Khartoum, where they may tip the scales in the favor of military and reactionary elements of the governing coalition. Were this to happen, the oppression and inequity which gave life to insurgency would remain in place, unless a serious and genuine effort at overhauling these structures were to occur. Currently available information suggests the peace process is intended to stabilize these structures, and not rebuild them anew.

Conclusion

The dynamics of violence in Sudan’s peripheries has evolved since the end of the ruthless counterinsurgency campaigns in 2016. Recurrent clashes between rebel and state-aligned forces have given way to intense, urbanized and ethnicized clashes across Sudan’s peripheries, joined by frequent attacks on IDPs and farmers enacted by militias linked to the semi-periphery. These dynamics have left only limited room for established rebel groups to carve out political and military space, and are not given serious attention by the peace talks being mediated in Juba. Attempts by rebel groups to reassert their power through formalizing and expanding their presence via the peace process will do little to improve the current situation given their near-irrelevance to the most serious violence in Darfur and the “Two Areas,” and may ultimately exacerbate it. These disturbing developments are taking place under the auspices of a peace process intended to prioritize national stability over questions of justice, representation and equality. Of particular concern is the potential for rebel groups to become part of a reactionary alliance, taking their place alongside paramilitary and security elites in Khartoum, and entrenching militarized rule in the peripheries. Currently, only the Abdelaziz al-Hilu SPLM-N faction and their new partners in the SPA have the potential to advocate for a principled break with this reactionary order.

In the second analysis piece in this series, these developments will be located alongside changes in the core of the country, where the shadow of the RSF has spread as dissatisfaction with the performance of the transitional government mounts. In the third and final analysis, both the situation in Sudan’s periphery and its core areas will be situated within changes rippling through the Horn of Africa.

Part of the author’s time was supported by the European Union’s Horizon H2020 European Research Council grant no: 726504

Appendix: SLM/A Abdul Wahid Factions

In addition to fighters and commanders loyal to Abdul Wahid, various splinter groups and sub-factions exist in and around Jebel Marrah, and have a limited presence in Libya. A more established splinter group is the SLM/A-Transitional Council, whilst elements of the mainstream group are based in the IDP camps of Hamadya and Kalma, which collect taxation to pay to Abdul Wahid. Below is a table of the various splinter groups and sub-factions.

| Commander | Information on Activity |

| Yusif Ahmed Yusif ‘Karjakola’ | Karjakola leads a semi-autonomous faction based in Libya, which includes the ethnic Zaghawa commander Salah Juk |

| Osman al-Zayn | Killed following 2018 clashes with Abdul Wahid’s (marginalised) military commander, Abdelgadir Abdelrahman Ibrahim “Gaddura”, with whom Osman al-Zayn had a rivalry with. His death spurred increased factionalisation. |

| Saleh Borsa | The nominal head of the reserve force of the rebel movement, but has engaged with clashes and side-switching with numerous other factions |

| Mubarak Aldouk | Former deputy of Osman al-Zayn, who defected to the government in 2019 following earlier clashes with loyalist commanders, and clashed with Saleh Borsa’s forces this summer |

| Faysal Adam Ali Konio | Former deputy of Osman al-Zayn, whose current status is unclear |

| Mohamed Taha | Loosely aligned to SLM/A Abdul Wahid military chief Abdelgadir Abdelrahman Ibrahim “Gaddura” |

| Zunoon Abdelshafi | Linked to Osman al-Zayn in early 2018, and now appears to be operating autonomously |

| Siddiq Al Fouka | Leads Sudan Liberation Army/Peace and Development sub-faction, which has defected to the government, and is based in northern Jebel Marrah |

| Jidu Tako | Leads a faction which defected to the government, and operates in southern Jebel Marrah |

| Amir Yousif Adam | Leads SLM-General Command faction. Limited information. |

| Yousif Ali Shag | Leads SLM-Field Leadership. Limited information. |

Sources: (UN Panel of Experts, 2019, pp.12-17, 23; UNSC, 29 June 2020, pp. 3,5)

© 2020 Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED). All rights reserved.