This is the second in a series of three analysis features covering unrest in Sudan, and the repercussions of this unrest for the wider region. Sudan is grappling with the legacies of decades of violence and quasi-military rule under the deposed President Omar al-Bashir, which has disproportionately affected marginalized areas of the country. The first piece, Riders on the Storm, explored recent patterns and trends in violence in such areas, focusing in particular on insecurity in Darfur and the “Two Areas” following the coup that ousted Bashir in April 2019, as a number of rebel groups prepared to sign peace agreements with the government. This second piece moves from the margins to the center, and analyzes unrest and political developments in the heartland of political power in the central areas of Sudan. In addition to assessing protest dynamics and suppression, the piece considers the implications of the arrival of paramilitary factions from Sudan’s semi-periphery of Arab-identified groups in the crucible of power in the country, notably the Rapid Support Forces paramilitary group under the leadership of Lt. Gen Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo (a.k.a. ‘Hemedti’). The final piece will pan further back to situate these developments in Sudan within the Horn of Africa, and considers the effects of involvement by external powers, and in particular from the Gulf states.

On 17 August 2019, the final documents for the power-sharing agreement between the Forces for Freedom and Change and the Transitional Military Council were signed in the Sudanese capital, Khartoum (Al Jazeera, 17 August 2019). These brought both revolutionaries and counter-revolutionaries into a transitional government, with a ‘technocratic’ cabinet and Prime Minister installed to oversee a supposed transition to civilian, democratic rule. Over a year later, on 31 August 2020, a number of weak rebel groups and obscure political parties from Sudan’s vast peripheries concluded peace talks mediated in the South Sudanese capital of Juba, paving the way for their incorporation into this ballooning and increasingly fractious transitional arrangement (Radio Dabanga, 1 September 2020).

These are landmark events for a country long under the grip of Omar al-Bashir and the National Congress Party (NCP, formerly National Islamic Front) and the remarkably durable autocracy they presided over. After almost thirty years of NCP rule, the regime buckled under a sustained popular uprising, before falling to a coup orchestrated by the highest elements of Bashir’s security empire. The first analysis of the series examined violence, paramilitarism, and rebellion in Sudan’s peripheries in light of these events, arguing that there are reasons to be concerned about the nature of the peace process and the effects it may have for intensifying violence in these marginal areas. Further, that analysis raised the possibility that the integration of rebel movements may help strengthen a reactionary peace which prioritizes stability over change.

This second analysis concentrates attention on the dynamo of Sudan’s political, economic, and military life, which is the riverain core of the country. Comprising Khartoum and the main towns and cities of central and northern Sudan, and overseeing vast agricultural areas stretching to the southern and eastern margins of the state’s effective reach, this core has for generations been the political and economic heartland of Sudan. It is once again the epicenter of political change, as an array of military, paramilitary, and political players stake out their claims in the ashes of the Bashir regime.

Analyses of Sudan after the uprising have tended to present two broad directions for the country’s political future, namely an eventual transition to civilian, democratic rule, or alternatively a continuation of dominance by various branches of the security apparatus, perhaps under a democratic façade. This analysis leans closer to the second of these predictions, but draws attention to the fundamentally changed political economy of Sudan after the loss of oil-rich South Sudan in 2011. This rapid decarbonization of Sudan’s political economy is the unseen force pushing events in Khartoum to their current predicament over the past decade. Now that the regime has collapsed, an additional force is shaping the transition underway, namely the interaction of military, paramilitary, and (to a lesser extent) rebel forces, with each broadly representing the core, semi-periphery, and periphery of the country, respectively, and possessing distinctive relations to regional and international patrons. These dual transitions – the abrupt decarbonization of Sudan’s oil economy, and the movement of rebel and paramilitary elites from the periphery and particularly semi-periphery to the core of Sudan – will mean that if rule by military elites in Khartoum is to continue, it cannot continue in the same way as before. How the contending power blocs in Khartoum respond to these circumstances will either infuse Sudan in further violence, or limit it to specific parts of the country.

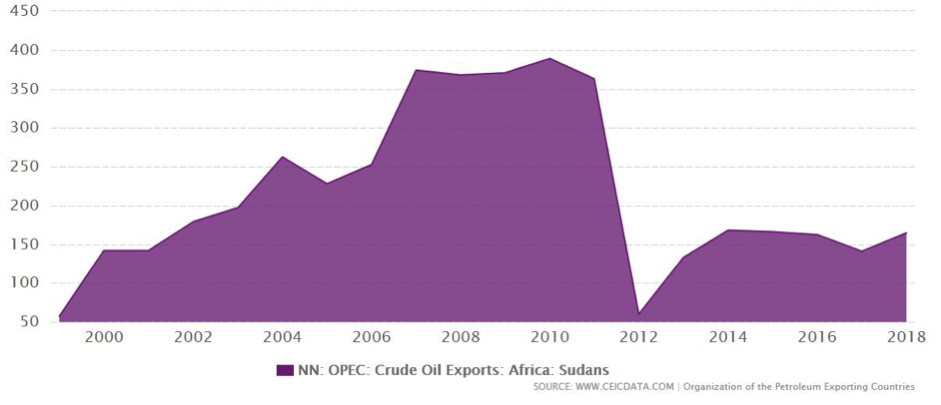

In the first section of this analysis, sequences and patterns of protests are analyzed, advancing an understanding of the uprising as being the delayed reaction to the rapid decarbonization of Sudan’s economy following the loss of South Sudan in 2011, which removed almost 75% of Sudan’s oil fields. The geography of protests as well the socio-economic profile of the organizers of demonstrations suggests that the discontent in the core of Sudan was spurred by fears that the urban middle classes would slide into inescapable precarity and hardship. The solutions put forward by these protesting groups were intended to substantially reform rather than replace the decaying political and economic order.

In the second section, the spreading violence in core areas is discussed in relation to developments in Khartoum. Whereas previous rounds of violent struggle in Sudan have tended to play out in select parts of the vast rural peripheries, large tracts of Sudan are now experiencing simultaneous violence, including the core. Whilst the violence in the central regions is not as embedded or complex as in the peripheries, an increasing tendency towards massacres and ethnicized clashes that temporarily paralyze urban centers is a serious concern, and may increase along with political uncertainty in Khartoum.

The final section explores the dynamics of the current political instability in Khartoum, and outlines ways this instability may evolve. The near-unchecked power of the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) paramilitaries under their charismatic leader, Lt. Gen Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo (a.k.a. ‘Hemedti’), introduces great uncertainty at the seat of power in Sudan. How Hemedti engages with the military and political establishment of Khartoum will be decisive in regulating levels of violence in the country. The analysis concludes by contending that Sudan’s post-oil economy will not be able to sustain consolidation by any one faction – be they military or paramilitary, revolutionary or counter-revolutionary – and that either a violent or less violent, relatively coordinated decentralization of power away from Khartoum are the likeliest eventual outcomes of Sudan’s dual transitions. Such a process will flatten some of Sudan’s stark power asymmetries, though the smoothness or otherwise of this decentralization will be decisively shaped by the degree of consensus or dissensus on the part of contending military and paramilitary elites, each backed by regional and external powers enmeshed in Sudan’s protracted crisis.

The Canary in the Coal Mine: The Uprising in Sudan’s Heartland

After President Omar al-Bashir was deposed in a coup on the night of 10 April 2019, a cabal of military, security and paramilitary elites rebranded themselves as the ‘Transitional Military Council’ (TMC) and attempted to establish a successor regime to Bashir’s embattled government. After initial missteps, which resulted in the resignation of Lt. Gen. Ibn Auf after one full day of rule, and the removal of the National Intelligence and Security Services (NISS) spymaster Salah ‘Gosh’ shortly afterwards, power in the junta was concentrated in the figures of Lt. Gen Abdel Fattah al-Burhan of the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) and Hemedti of the RSF, both of whom are notorious for perpetuating human rights abuses during military operations in Sudan’s peripheries (Africa Confidential, 19 April 2019; Foreign Policy, 2019; Global Witness, 2019).

These military and paramilitary elites – who now represent the upper echelons of the sprawling and unevenly powerful security apparatus – have continued to dominate the transitional government and Sovereign Council. These institutions had been formalized on 17 August 2019 with the Forces for Freedom and Change (FFC), a loose conglomeration of labor and activist groups conjoined with several establishment opposition political parties (see Corda, 2020 for a striking set of visualizations). This agreement created a sense of stability in the capital following months of demonstrations and the massacre on 3 June (discussed below), and such an accommodation between the FFC and the security services was the predictable outcome after months of entreaties for military intervention by the Sudanese Professionals Association (SPA, a trade union for middle class professionals, discussed below) (Deshayes and el Gizouli, 2019).

During his lengthy reign, President Omar al-Bashir built a continually shifting pyramid of power, in which political barons and military, paramilitary, and intelligence elites could find themselves not only moving up or down, but also sideways across a range of positions in the multiple security organs, party bureaucracy, or in the state governments of the remote and volatile peripheries. As Alex de Waal summarized, Bashir was “the spider at the center of the web – he could pick up on the smallest tremor, then deftly use his personalized political retail skills to manage the politics of the army” (New York Times, 11 April 2019). Much of this elite politicking either came at the expense of the rural non-Arab poor of Sudan, or was simply pursued without regard to them.

In this respect, the NCP regime represented an extension of previous governments in Sudan, and maintained the neoliberal leanings present in the Sudanese ruling elite since the 1970s. The most visible distinction between Bashir and his predecessors was the overtly Islamist character of the regime during the 1990s, with Islamist politicians and business communities having gained significant ground in the country in the 1980s. Yet the strength of Islamist party and security elites had diminished greatly by the eve of Bashir’s downfall, and had limited appeal to the younger generations whose political and economic aspirations were blocked by the party, state, and security organs of the NCP regime. Instead, the bases of support for the regime were found in the affluent urban elite, a salaried urban middle class which had expanded along with the oil boom after 1999, and the army and rival security bodies. This was a transactional relationship which depended on the regime satisfying the needs of these constituencies, which, in turn, required Bashir to also keep external patrons (especially from the Middle East) onside to provide vital financial support. The regime focused on a ‘substantial minority’ of the population (Verhoeven, 2013), in a strategy which rested on catering to the needs of wealthier Sudanese in the core of the country, whilst keeping special interest groups and external patrons onside. Beyond this balancing act, there were additional pressures to provide continued resources and opportunities to the military and security organs that proliferated in number and size under Bashir (El-Battahani, 2016; Deshayes and Raphaëlle Chevrillon-Guibert, 2019).

A revolt from the middle classes was a concern insofar as it could sow discord or invite intervention from the security organs. Put simply, dissent towards the bottom of the pyramid could spread upwards in unpredictable ways, and unravel the network of alliances and obligations supporting the NCP system.

The decision to incrementally lift subsidies on flour and fuel proved a step too far for the lower strata of this ‘substantial minority’ that had been courted by the NCP, ensuring that anti-regime demonstrations convulsed the capital and other major towns of the riverain core of Sudan. This decision was taken, in part, because of the increasing strain placed on the flour subsidy system which had existed since the late 1960s. The flour subsidy made bread cheaper, and functioned reasonably well when bread was only eaten by the urban middle and upper classes, as was the case in the 1960s. This system became overwhelmed due to a combination of corruption in the chains of supply and distribution, as well as swelling urbanization – itself fueled by decades of forced displacement from peripheral rural areas – leading to greater demand for bread by social groups who did typically ate sorghum prior to their arrival in urban areas (Thomas and el Gizouli, 2020: p.2).

This occurred in the context of a slow-burning economic crisis and the permanent austerity caused by the secession of South Sudan, in which the newly established petro-economy of Sudan had to adjust to the sudden loss of nearly three-quarters of its oil fields, and its primary avenue for accumulating foreign exchange reserves. Minus the oil, South Sudan would have been a burden to Khartoum, given its minimal engagement with the modern cash economy and its truculent rebel groups. Yet Khartoum’s efforts in the 1990s at hiring irregular Bul Nuer paramilitaries to cleanse oil-producing areas of the South of rebels and civilians – in conjunction with extensive Chinese assistance and engagements by several minor Western oil companies – finally brought oil production online in 1999, overhauling the economic relations between North and South (Patey, 2014).

The decarbonization of Sudan’s economy has taken place with frightening speed, and has set off a chain reaction which has taken the country to its current predicament. Attempts at exploiting various external channels for resources – including leasing the RSF to the campaign in Yemen led by Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and to the European Union’s anti-immigration patrols in North Africa – were unsuccessful in plugging the gap. War in South Sudan has had a severe effect on oil production, which is now far below pre-independence levels, greatly depleting revenues Sudan had hoped to obtain through overcharging the South for use of pipelines running to Port Sudan (see Craze, 2020: p.3). After a questionable scheme by the Central Bank to purchase gold from artisanal miners and recycle this gold wealth through the UAE in exchange for hard currency resulted in soaring inflation, the government followed IMF recommendations to reduce subsidies and tariffs in early 2018, exacerbating hardship in towns and cities and eroding the incomes of those on fixed salaries (el Gizouli, 2019; de Waal, 2019: pp.12-16).

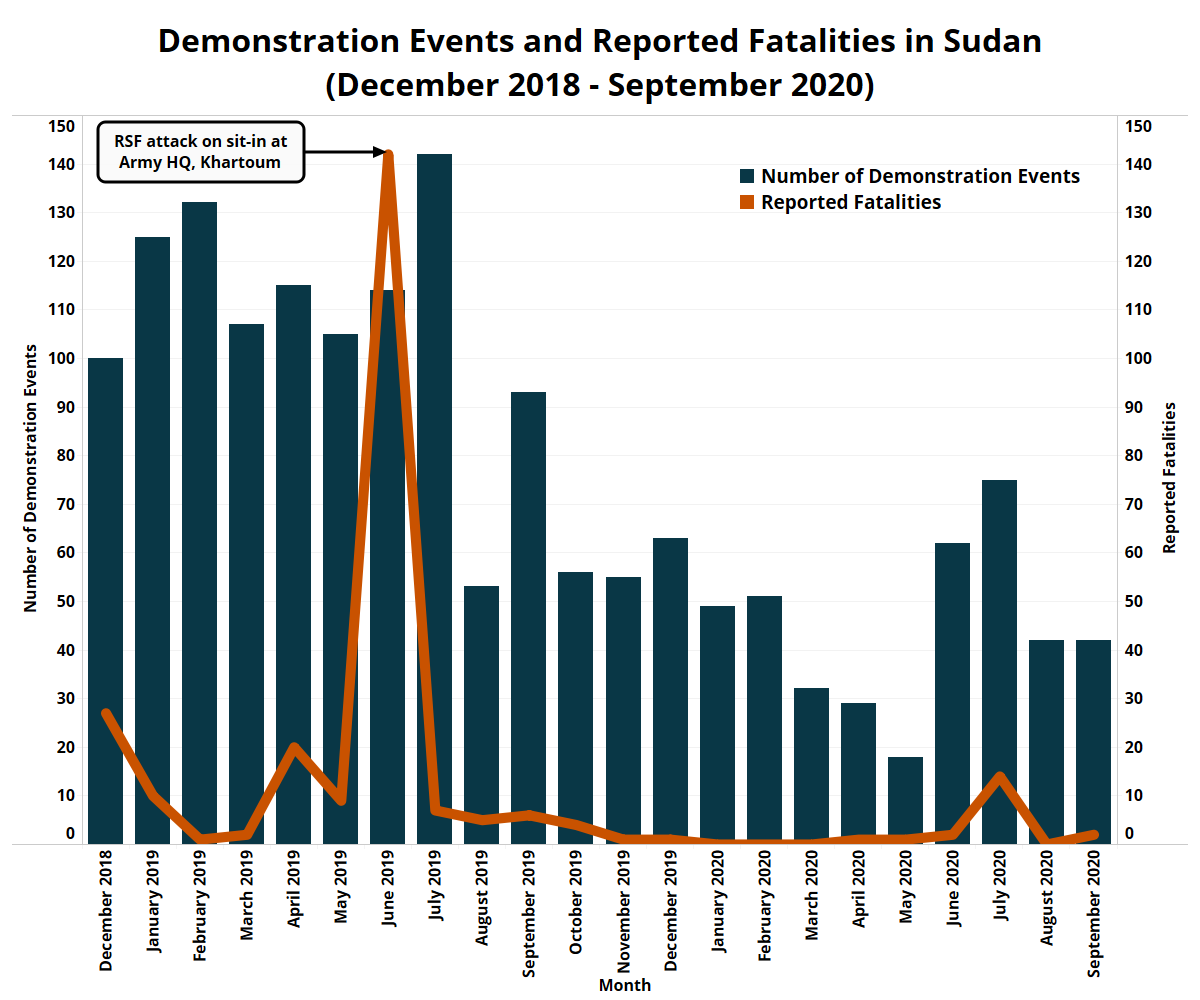

It was in the context of this protracted economic collapse that large numbers of protesters could be mobilized, with the further reduction of subsidies in December 2018 catalyzing urban unrest. From the beginning of protests in Sennar state on 7 December 2018 to end of 2018, a total 98 demonstration events relating to cuts to subsidies or calling for the overthrow of the NCP were recorded by ACLED. Protests spread to Ed Damazin on 13 December, and then on to Khartoum and El Obeid, and reached Atbara on 17 December. At this point, demonstrations became anchored in urban areas, with increasing involvement by the SPA. As the uprising continued into 2019, 1,100 demonstration events were recorded by ACLED over the whole year, the bulk of which took place in the first six months and with a majority of such events occurring in urban areas of the core. This surge in protest events is unmatched in Sudanese history, far outstripping the last period of serious unrest in 2013 in terms of the number of protests and riots.

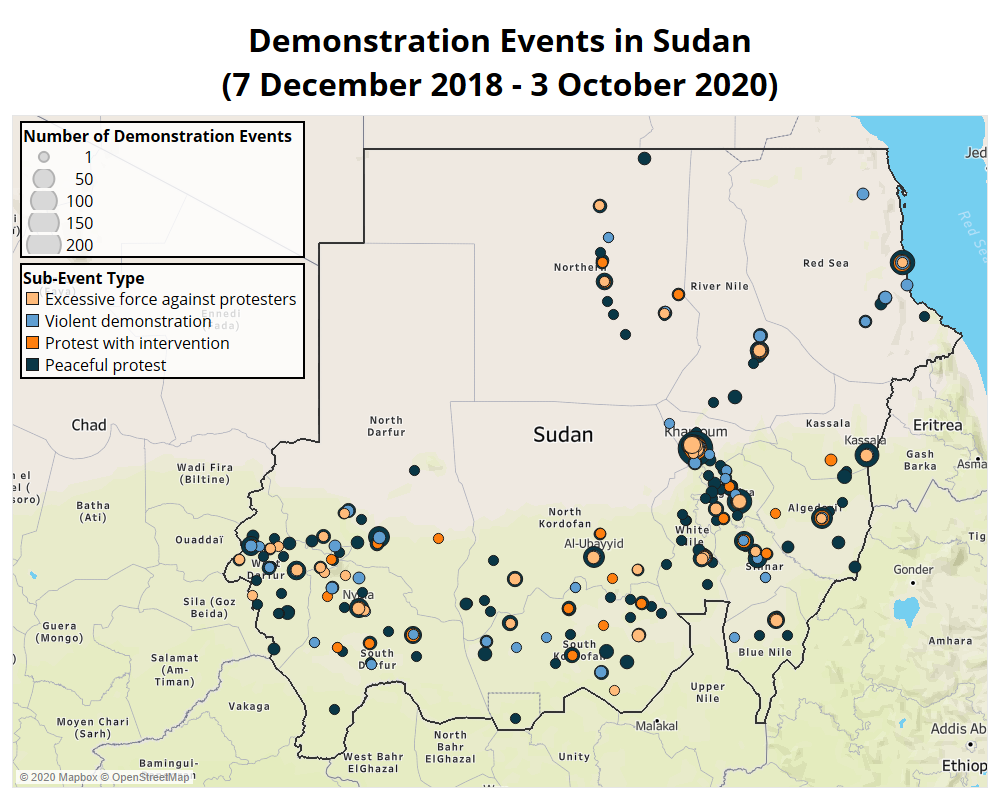

Initial demonstrations were in opposition to subsidy cuts and soaring prices, which threatened to drag large swathes of the urban lower and middle classes into deeper hardship usually reserved for members of the rural and displaced periphery. The protests then took on an anti-Bashir and anti-NCP character. The fact that demonstrations clustered in larger cities in the core (see map below) speaks in large measure to the fact that residents of these areas had more to lose from the deteriorating economic situation, whereas those in marginal (and especially rural) areas were more accustomed to desperate hardship. Rioters in Atbara, Dongola, Gedaref, and Khartoum torched local NCP offices in late December 2018, as the SPA assumed a central role in organizing demonstrations, and articulating a center-left vision of political reform. Although violence against demonstrators did occur during this month, considerably more restraint was shown on the part of the state than would have been granted to those in marginal areas.

The first major instance of violence relating to the uprising occurred in Gedaref on 20 December 2018, when police killed 12 and wounded dozens of rioters (including students) who had torched various municipal buildings and the NCP headquarters in the city, and attacked security vehicles. Fatalities from demonstration events overall stand at around 200 between the start of protests on 7 December 2018 to the signing of the final set of agreements that ushered in the transitional government on 17 August 2019, compared to 342 deaths throughout the last major anti-government demonstrations in 2013. This is in line with a gradual reduction in the levels of attacks, torture, and arbitrary arrests employed by the Sudanese state to deal with unrest observed over recent years, even if this restraint is felt less in ghettoized areas of cities largely inhabited by poor and displaced non-Arab ethnic groups (Deshayes et al., 2019). The reduction is due to Bashir’s awareness that a combination of economic hardship and indiscriminate violence would erode support at the upper levels of urban society, risking a chain reaction which could lead to a coup. The size and spread of the recent demonstrations also made systematic repression more challenging for authorities.

As the figure below illustrates, following the surge in demonstrations from the end of 2018 to mid-2019, there has been a decline in the number of demonstration events, although it has been on an upward trajectory during this past summer. Whilst it is difficult to come by reliable information on demonstration size, media reporting indicates that during the dip after mid-2019, the numbers attending demonstrations declined markedly, with demonstrations over the past three months seeing a return to very large crowds of demonstrators.

After progress was made towards a power-sharing agreement in mid-2019, the trend has been for protests to split off into various sub-strands of the national-level struggle. These include demonstrations against unpopular military governors and controversial politicians, and frequent calls for purges of local administration and institutions of NCP officials as part of efforts at dismantling the ‘deep state’ (discussed below).There have also been calls for improvements in labor conditions in the public and oil sectors. Meanwhile, protests against localized and specific grievances have become staples of rural areas and small towns. Recurring themes includes land disputes (often involving land sold in desperation to investors from the Near and Middle East by the cash-strapped Bashir government), environmental destruction caused by harmful gold refining processes in South Kordofan and Northern states, and increasing sit-in protests against insecurity in numerous parts of Darfur.

Some of these sit-in protests have been brutally dispersed by militia from the semi-periphery, as in Fata Borno (killing 10) and Misterei (killing 2) during July, prior to heavy fighting between Rizeigat and Masalit militias in Misterei which killed 77 at the end of July. Solidarity rallies in Khartoum have been held in the wake of such attacks, whilst excessive intervention by security forces tends to cause a ripple effect of protests in major towns and cities. Periodic rallies by groups who suffered violent dispossession and displacement have occurred intermittently across much of the country, including among those displaced to make way for the Merowe dam, and to commemorate victims of the 2005 Port Sudan massacre. Notably, there have been a small, but growing, number of protests by Arab-identified pastoralist communities calling for peaceful co-existence with African groups (Radio Dabanga, 31 August 2020; Radio Dabanga, 2 September 2020).

In recent months, protests against soaring prices, shortages of basic goods, and inadequate service provision have surged, often replicating the sit-in format recently used by Darfurian protesters. Cumulatively, the various issues animating protests have become increasingly disparate and disconnected from national-level politics as disappointment with the accomplishments of the FFC and transitional government set in. However, these more specific grievances have fed into much larger demonstrations commemorating landmark events in the uprising over the course of this summer, which have now taken an overtly critical stance towards the FFC. Also taking a critical stance have been a number of Islamist-organized protests, including successor organizations to the NCP. These protests have exclusively taken place in large cities, and protesters have recently begun to call for a military coup to dislodge the FFC administration. These demonstrations have been irregular and generally poorly attended, indicating that a mixture of stigma, unpopularity, and a lack of experience in conducting organic demonstrations is preventing such groups from translating their disdain into meaningful action.

Repression, Revenge, and the Rapid Support Forces

Since the removal of Bashir by his own security elites, levels of violence in the core have soared after several years of dormancy. The central areas of Sudan have typically been insulated from Sudan’s civil wars, which have been largely fought between impoverished groups in the peripheries, with Khartoum and its rivals in neighboring capitals attempting to influence the course of conflict to their advantage. Successive Sudanese governments have become more adept at containing their exposure to violence, whilst also limiting its spread to specific areas of the country, so as not to overwhelm the security system.

This has changed since the collapse of the Bashir regime: violence is now present in both the core and in several peripheral areas. Such a coexistence of core and peripheral violence is not unprecedented in Sudan,1The Greater Khartoum area has been the site of periodic episodes of intense violence relating to instability at the national and regional level, including lethal riots following the death of Southern rebel leader Dr. John Garang in August 2005.In May 2008, an audacious attack from Chadian-backed Justice and Equality Movement rebels on Khartoum’s sister city of Omdurman saw the capital saved by intervention from National Intelligence and Security Service soldiers. Deadly violence has also accompanied the 2013 demonstrations in the capital. but now takes place amid a scramble for political control in Khartoum, and in a dire economic situation where the country lacks sufficient finance to buy its way out of a crisis.

While under pressure from protesters in 2013 and 2018/19, Bashir increased the presence of the RSF paramilitaries in the capital, both as a means of suppressing unrest and warding off a potential coup. The growing military and financial power of RSF leader Hemedti was tolerated by Bashir as part of his continued efforts to rearrange power within the security apparatus, though it has become increasingly unchecked since 2017, when Hemedti wrested control of lucrative gold mining sites from ex-Janjaweed leader Musa Hilal (de Waal, 2019: p.14). With the movement of the RSF to the central belt of Sudan, and of Hemedti to the position of Deputy Chairman of the Sovereign Council, these problems have now moved from the margins to the center.

The bulk of the fatalities relating to the uprising happened after Bashir fell, when on 3 June 2019 RSF paramilitaries (likely operating alongside members of the police and NISS) attacked the large sit-in camp near the army headquarters, killing over a hundred people amid reports of widespread sexual assault (see figure above; Amnesty International, 2020; El Gizouli, 2019b). Hemedti has unconvincingly attributed the massacre to imposters dressed in RSF uniforms, whilst reports of an official inquiry into the killings have been repeatedly postponed. Such delays have sparked further demonstrations by activists, who are understandably concerned that the inquiry is intended to obfuscate the role of the senior RSF commanders and security elites in organizing the massacre. RSF paramilitaries have been repeatedly linked to excessive violence during counterinsurgency campaigns in the restive peripheries (Human Rights Watch, 2015), and to killing protesters in Khartoum during the 2013 demonstrations (El Gizouli, 2019b). Their involvement in the 3 June massacre suggests a calculated decision by Hemedti to assume a dominant function in regime security, as the various instruments of regime policing under Bashir – including NISS, the Popular Police and Popular Defence Forces, and Public Order Police – were being pushed into history by the SAF.

Hailing from a background in cattle trading in the far west of Sudan, Hemedti was outside of the military and political establishment, and, in theory, bringing his forces to Khartoum strengthened Bashir’s hand against a potential coup plot in the military and intelligence agencies during the uprising. Ultimately, when the coup did occur, Hemedti would side with the coup plotters, though was reportedly the last to know about the plans they had hatched (Reuters, 3 July 2019). Bashir reportedly saw things differently, claiming at the moment of his removal that Hemedti and NISS director Salah ‘Gosh’ were acting on behalf of the Saudi-Emirati-Egyptian bloc (El Gizouli, 2019b), whom Bashir had enjoyed an on-off relationship with that had recently soured after he turned to rival Gulf state Qatar for financial assistance.

The RSF are not only geographical and cultural outsiders to the riverain core of Sudan, but they sit outside of the bloated party and state bureaucracy of the NCP-era. At the senior levels, the state bureaucracy had become so ineffective due to cronyism and appeasement appointments that Bashir established a parallel system of rule by powerful committees on matters such as defense or economic policy to bypass the political debris which had accumulated over three decades of rule (El Gizouli, 2019b). The RSF is poorly represented in such structures, presumably because Bashir had hoped the RSF could rebalance the security terrain in his favor by remaining only loosely connected to the system, helping to prevent a coup from the better integrated SAF and NISS. As noted in the first analysis piece in this series, Hemedti has been an active force in both negotiations with rebels from the periphery, and in a concurrent set of internal negotiations on ethnicized violence in various parts of Sudan, and more recently in the disputed Abyei area (Sudan Tribune, 26 August 2020). This indicates that Hemedti is forging alliances between the semi-periphery he purports to represent as well as elites from the periphery, whilst making inroads on the diplomatic circuit.

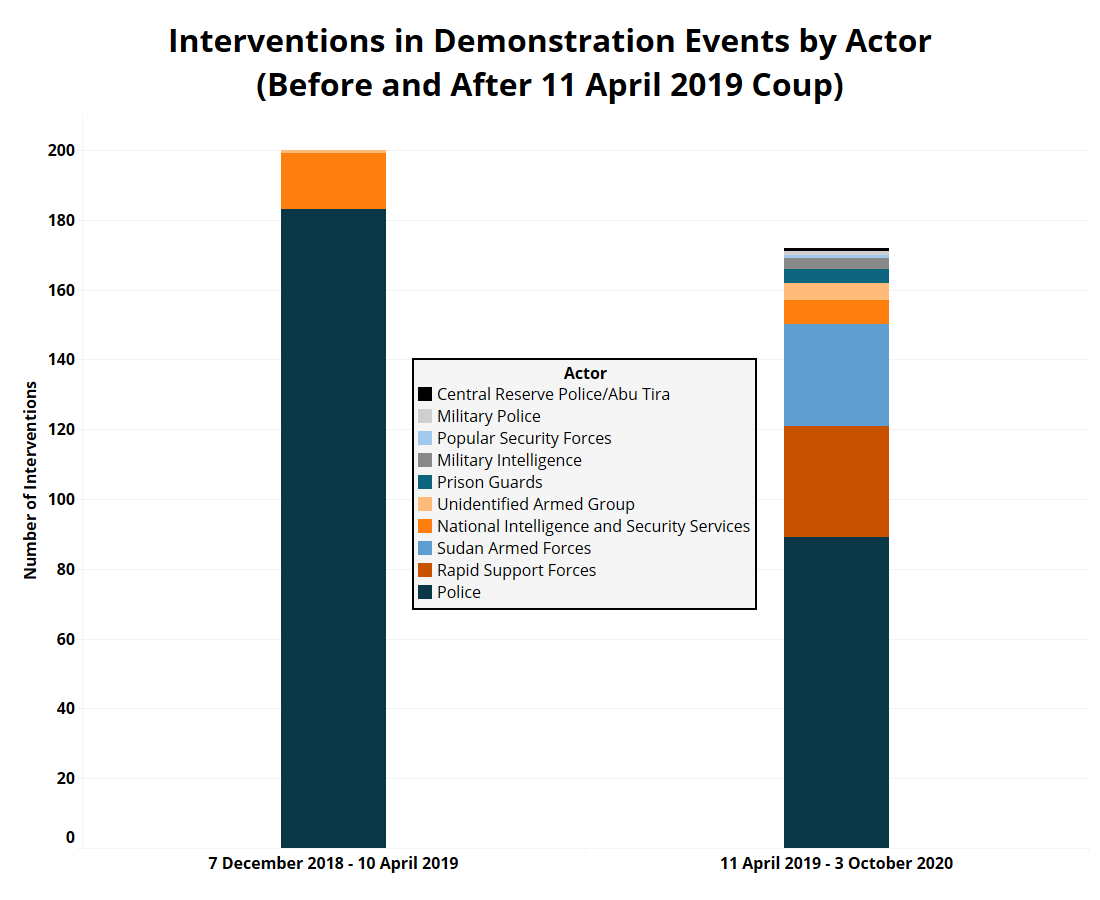

Suppression of protests has continued since the fall of Bashir and the 3 June massacre, with the RSF and SAF responsible for a greater number of interventions in demonstrations and sit-ins (see figure below). There has been a substantial decline in repression by regular police forces since Bashir’s removal, though this has begun to rise in 2020. Due to a political pincer movement by SAF and RSF elites in the TMC, NISS (now renamed General Intelligence Services, as of late July 2019) has seen its operational size and scope severely reduced, accounting for the decline in NISS engagement with protesters.

In mid-January 2020, a large number of former NISS soldiers from the Operations Authority division (the sizable armed wing of the intelligence agency) staged a dramatic mutiny in Khartoum and Khartoum North, and in El Obeid in North Kordofan. Conflicting accounts of the mutiny have been advanced, ranging from concerns by the NISS soldiers awaiting demobilization that their pay-out package had been siphoned off, to unconfirmed reports of unrest stirred up by elements of the NCP security cabal (StillSUDAN, 2020). At least five were killed in fighting involving RSF and SAF units against the former NISS soldiers in Khartoum, including three civilians who died after a shell hit their house in the Soba neighborhood of the capital.

Whilst these events are troubling, concerns that remnants of the NCP will destabilize the transitional government are likely to be overstated. NCP militias active in the capital during demonstrations (see Appendix below) appear to have melted away, whilst the Popular Defence Forces (PDF) paramilitary group was finally disbanded in June of this year (Radio Dabanga, 21 June 2020). There has been little solid information on the fate of the various police forces linked to the regime (including the Public Order Police and Popular Police Forces), though it is likely that they have been (or will be) disbanded. To the extent that these forces pose a risk to stability in Sudan, this is more likely to be felt in the form of localized insecurity in areas where such forces enjoyed greater autonomy, with South Kordofan seeing an uptick in violence, theft, and score-settling attributed to PDF soldiers before and after their formal dissolution (see HUDO Centre, 2020).

The numerous paramilitary and quasi-regular police forces were among the more visible extrusions of the ‘deep state’ of the Bashir era, which senior members of the Sovereign Council have repeatedly linked to attempted coups as well as an apparent assassination attempt on civilian Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdock in Khartoum North in March of this year (Africa Confidential, 19 March 2020). Since the removal of Bashir, there have been regular protests denouncing the slow efforts of the transitional government in dismantling the ‘deep state.’

When assessing the threat potential of this ‘deep state,’ it is helpful to disaggregate this entity into what are arguably its central components, which include several layers, each with varying degrees of both loyalty and proximity to the upper echelons of power. The first layer are the parallel committees overseeing core domains of government (especially security, economic, and diplomatic functions), and which reported directly to Bashir. Second are Bashir loyalists clustered at senior levels of the security system, and the third are intelligence networks crossing through parts of the security, party, and bureaucratic core of the state. Beneath these more exclusive and influential levels are, fourth, widespread infiltration and co-option of civil society, NGO, banking, and business sectors by Islamist and security agents as well as cronies of the regime. Finally, a parasitic layer exists among the lower levels of public administration and subnational bureaucracies stuffed with NCP supporters, who have been the frequent targets of local demonstrations. Wealth, power, and personal security are the main interests of actors across the different elements of this assemblage, with each level enmeshed in economic activities and dubious enrichment opportunities, albeit at vastly differing scales.

Each level of this conglomeration has lost power and wealth since the coup, with the heaviest losses felt by those once at the most senior levels of the security system, many of whom have been retired or arrested by the transitional government. These losses have been further compounded by the transfer of power to the RSF, who have been accumulating the assets of the NCP regime. The strategy of lower levels of this system will be to hunker down and attempt to ride out the transition relatively unscathed. There are greater risks from senior intelligence and security officials who maintain connections and knowledge of weak points in the security system, who may be able to influence instability in the system in their favor. The chances of the NCP insiders seizing outright control of the transitional government is low, and it should be recalled that many of the current rulers from the TMC were in any case active members of this cabal under Bashir.

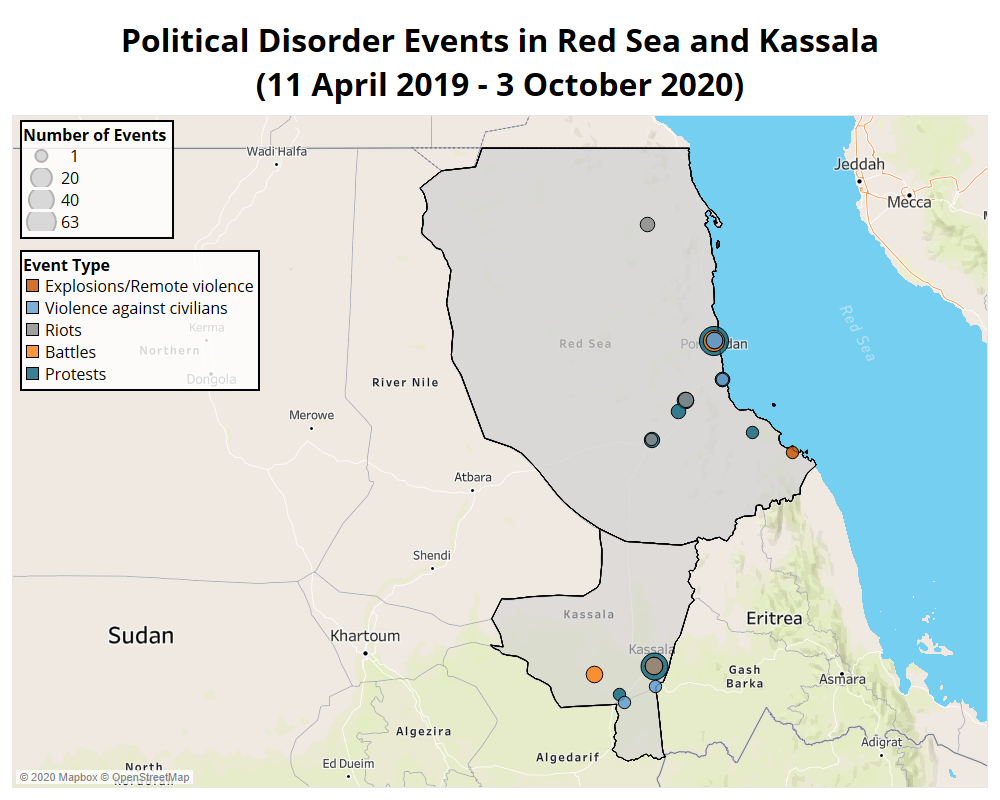

Violence and instability have spread outside of the capital, with the map below showing the two most affected areas, which are Red Sea and Kassala states. Although located outside of the riverain area, the city of Port Sudan in Red Sea state functions as an integral part of the core, supplying the interior with imports whilst also being the terminus for oil extracted from the southern periphery and from South Sudan. Notable events in Port Sudan include ethnicized clashes and riots between members of the Nuba IDP community (a collection of ethnic groups from the Nuba Mountains of South Kordofan state, not to be confused with the Nubian group near the Egyptian border) against the Beni Amir, and clashes pitting members of the Hadendowa branch of the Beja against Beni Amir (technically part of the Beja, but often regarded as a separate ethnic and linguistic group, see International Crisis Group, 2013). As ACLED data show, these clashes have resulted in 93 deaths since August 2019, and hundreds of injuries. Serious flare-ups have occurred in August 2019, January 2020, and August 2020, temporarily paralyzing activity in the city, and prompting heavy deployments of soldiers, including RSF. Separately, prison riots have also occurred in the city in response to the failure of authorities to uphold coronavirus safety measures. Port Sudan and nearby areas of Red Sea state have also been a hotbed of protest activity on both national issues and labor disputes.

Clashes between Hadendowa and Beni Amir in Port Sudan have been mirrored in Kassala state since May 2020, where at least 18 were killed in Kassala town this year (with unconfirmed local reports suggesting a death toll twice that figure) and well over a hundred confirmed wounded. The clashes relate to fears of marginalization by both groups in a context of national change and uncertainty, which have now become attached to the appointment of a Beni Amir governor by the FFC in July (Ayin Network, 1 September 2020; Ayin Network, 7 September 2020). Shifting ethnic clashes involving various displaced and migrant labor groups have also been reported in the town of New Halfa, though with far lower casualties. Prison riots related to inadequate coronavirus measures have also been reported in Kassala. More recently, deadlock over the appointment of the governor has escalated rhetoric, with Beja elites calling for self-determination for Beja-inhabited areas, which was swiftly rejected by elites from the Rashida ethnic group2The Rashida Free Lions were an armed group also active during the war in Eastern Sudan, but were politically and militarily overshadowed by Beja rebel factions. (Radio Dabanga, 30 September 2020; Al Rakoba, 3 October 2020).

Following the final signing ceremony of the Juba peace agreement on 3 October 2020, representatives of certain Darfurian communities denounced the agreement. A prominent member of the Darfur Displaced and Refugee Camps General Coordination pithily described it as “a peace of quotas and positions which does not represent the Sudanese people as much as the signatories” (Radio Dabanga, 10 October 2020).

Whilst there has been positive support for the agreement in several parts of Sudan, Eastern Sudan has not been one of them. Instead, the East has become the epicenter of demonstrations against the agreement, with infrastructure in Port Sudan and across Red Sea state being blockaded by striking workers and Beja demonstrators. Meanwhile, a police officer guarding an oil facility in Haiya (south-west of Port Sudan) was killed after armed demonstrators from the Hadendawa clan attempted to storm the facility (Voice of America, 7 October 2020). The unrest portends escalating discontent among parts of the Beja amid continued economic and political marginalization of Eastern Sudan, and increasingly overt expressions of ethnic chauvinism. The events follow from the quiet renegotiation of the Eastern Sudan provisions of the Juba peace agreement that had originally been signed in February, after Hadendowa elites contested the terms of the agreement, some of which may have been lifted from a partially implemented agreement from 2006. The outcome of these renegotiations remains unclear. The version of the Eastern Sudan accord signed this February allocated 30 percent of local administration positions to the former rebel groups who negotiated the agreement, with demobilized fighters receiving an unspecified set of benefits (Radio Dabanga, 28 February 2020). At least some of the anger directed towards the agreement reflects irritation by those excluded from its benefits, who have accused the three factions that signed the agreements of being complicit in a conspiracy from the Bashir-era to re-engineer the ethnic composition of Eastern Sudan to dilute Beja influence (Radio Dabanga, 9 October 2020).

Whilst it is too early to tell whether a return to low-intensity war that rocked Eastern Sudan from 1995-2006 is on the cards, the immediate risk is an intensification of ethnicized urban violence. This could spiral if security units begin to overtly take sides, and possibly invite Eritrean involvement. The interaction between the Juba peace agreement and the failure of contending local elites and Hemedti to negotiate durable internal agreements (see Reuters, 8 September 2019) has compounded rivalries among Eastern Sudanese political blocs, and allowed ethnic paranoia and provocation to increasingly dominate political developments in the East.

Violent events in Khartoum, Red Sea, and Kassala states, as well as recurrent demonstrations in the major towns and cities of the core, have accompanied the intense political instability in the capital, and it is reasonable to presume they will continue to do so for as long as this instability persists. In the final section, the dynamics of political instability will be discussed, before concluding with an overview of likely trajectories of Sudanese politics, and their implications for violence in central and marginal zones of the country.

Sudan’s Dual Transition: Confronting Decarbonization and Militarization

Political coups and popular unrest have been the harbingers of change in Khartoum, which invariably ripple across the marginalized areas of Sudan, and reconfigure political and military alignments in the Horn of Africa. The hyper-concentration of power in this core is the result of Sudan’s convoluted colonial experience, and has undergirded the economic and political injustices and the complex patterns of militarization that have animated the country’s numerous civil wars (de Waal, 2007; Ayers, 2010). Waves of expropriation and the one-way flow of wealth from the peripheries to the center have created uneven wealth in the center, and resentment in the peripheries.

Sudan’s current crisis is at the core of the country, but is greatly complicated by the consequences of its rulers’ actions in the peripheries, and particularly in Darfur. Among other things, near-constant wars in the peripheries and coup-proofing in the center has created a surplus of armed men linked to both regular and irregular forces, and an expensive military-industrial sector concentrated in the capital, both of which the country may no longer be able to support. In remote areas, the government’s counterinsurgency strategy has fragmented the states’ control of distant regions, with rebel and paramilitary leaders stepping into these vacuums, and the RSF expanding beyond their original domains and into the central and eastern areas of the country. During a time of tension, there is no reason for the military and security elites to reduce the size of their own forces.

As the uprising progressed through 2019, Western commentators from the political center ground articulated a narrative that misrepresented political dynamics in Sudan as a struggle between democratic and largely civilian forces attempting to liberalize Sudan’s political structures, with an old guard of Islamists and security elites seizing opportunities to prevent such changes and drag the country back into a variant of the NCP regime. It is becoming increasingly clear that this is not the case, due to a combination of shared interests (if not collusion) among the Sudanese political and military establishment, as well as external meddling (with the latter discussed in the forthcoming, final analysis piece in this series).All this occurs in the context of the damage caused to Sudan’s power structures as a result of its rapid decarbonization. As argued above, it was the economic upheaval caused by the dramatic loss of oil revenues which spurred the uprising, with calls for a more democratic and inclusive rule becoming attached to the ripple effects of this crisis in Sudan’s political economy.

The final power-sharing documents signed in August 2019 envisage a 39-month transitional period. This length seemed to satisfy the interests of various constituencies. It allows the majority of the security organs time to consolidate their economic power whilst maintaining a dominant role in domestic and foreign policy, which in turn benefits Khartoum’s foreign partners. External regimes – and in particular Egypt and South Sudan – seek stability in Sudan, which they equate with continued military or quasi-military rule.

On the part of civilian components of the FFC, the length of the transition reflects lessons learned from labor groups who spearheaded previous uprisings in the core from 1964 and 1985. Shortly after an alliance of trade unions and military officers unseated autocratic rulers in both years, Sudan’s aristocratic and conservative political parties (the National Umma Party (NUP), and the Democratic Unionist Party) worked to hold elections swiftly in order to resume power, undermining the more progressive labor groups and their supporters among students and civil society (Berridge, 2020: pp.167-68; Deshayes and el Gizouli, 2019). In theory, a longer transitional period may help to keep such parties at bay and enable youth and labor groups to create alternative political parties or coalitions. In practice, the transitional period has served to benefit those who already possess power in the political sphere, setting the stage for a struggle between more radical and conservative elements of the FFC.

The FFC’s greatest strength is also its most acute weakness. It is a very broad church, comprising neighborhood-level Resistance Committees that were clandestinely formed during protests in 2013; labor groups of various political leanings, most prominently the SPA, which represents salaried, middle class professions; operating alongside civil society and opposition political parties, including the conservative NUP of former Prime Minister Sadiq el-Mahdi as well as the Communist Party. As such it has links to a considerable number of constituencies, and more than any one element of the alliance could reach by itself. Unfortunately, this comes at the expense of coherence and unity, making the entity as a whole vulnerable to dissensus, deadlock, and co-optation.

Since the coup, power within the FFC has shifted away from the SPA and Resistance Committees that led the anti-government protests and towards established political parties, in a process which has seen the different elements turn against one another (Gallopin, 2020). The beleaguered Prime Minister, Abdallah Hamdock, has recently replaced the military governors who had been installed in the final months of the Bashir regime. However, this has sparked disputes among the FFC due to the appointment of non-FFC governors in several states, as well as the heavily male-dominated composition of the governors. The appointments also prompted the conservative NUP to further distance itself from the alliance after they received six governor positions, having wanted eight (Ayin Network, August 2020). NUP leader Sadiq el-Mahdi subsequently called on the “patriotic” SAF and RSF to join an alliance against “Islamist apostasy and secularist deprivation,” in a strange speech that identified a plot supposedly being hatched by Sudanese Communists, secularists, and the American Evangelical right to divide the country (Sudan Tribune, 31 July 2020). Such statements, whilst being rather transparent examples of opportunism and manipulation, are concerning because they demonstrate the comfort that establishment civilian politicians have with military domination, and could presage a formal alliance between conservative civilian politicians and reactionary military elites to legitimize continued military rule.

In a serious blow to the progressive credentials of the FFC, the center-left SPA withdrew from the alliance altogether on 25 July of this year, entering into an alternative alliance with the Abdelaziz al-Hilu faction of the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-North rebel group, who did not sign the Juba peace agreement. This leaves an increasingly marginalized and wary Communist Party to represent a progressive voice in the FFC, and Resistance Committees on the streets. Resistance Committees have taken a prominent role in protests over the past three months, which have been partially directed against the failings of the FFC. However, the benefits accrued and burdens shouldered by different branches of the Resistance Committees are largely determined by the existing class order of Sudan, preventing more radical elements from accessing national power. As noted by Magdi el Gizouli, Resistance Committee members from affluent districts of Khartoum have been able to step into the shoes of the defunct NCP-organized Popular Committees (which governed neighborhoods, issued essential documents, and policed morality) and even engage with more senior levels of the FFC. This is in contrast to Resistance Committee youth from deprived areas, who have essentially been abandoned since the transitional government was inaugurated. This risks splitting the youth voice, with co-opted elements from relatively wealthy areas risking “incorporation into the state machinery as pawns of authority in their local spheres” (El Gizouli, 2020, p6).

The gradual disintegration of the FFC works to the favor of counter-revolutionary forces, as does the ousting of more radical elements. Among the counter-revolutionaries, a distinction can be drawn between those members of the (mostly Khartoum-based) political, military, and economic elite who are broadly keen for the status quo to continue, albeit with some adjustments from the NCP-era, and those elements from far-flung areas of Sudan that wish to rewrite parts of this consensus and substantially increase their own power.

In the first camp are the majority of the regular security chiefs, the conservative political parties who had dominated civilian politics prior to the 1989 coup, and technocratic elements of the FFC. The adjustments they seek include a reduction in political and economic instability as well as violence, whilst obtaining international legitimacy. This requires the counter-revolutionaries to finally discard outright Islamist characteristics that lingered from the first half of Bashir’s rule, and which have impeded the elite’s ability to access Gulf patronage and capital whilst normalizing the country’s international status. Whilst there will be areas of disagreement – including on the extent and nature of democratic participation, as well as the power of civilians and the civil service in decision making – this camp represents a coalition hoping for the continuity of rule from a powerful core. This would effectively leave Sudan’s lopsided and extractive power structures intact.

In the other camp, headed by Hemedti, the current conjuncture in Sudan provides an opportunity to prise open this established order, and reorient power from the core to the semi-periphery. Power has been gradually transferred from the center to the semi-periphery of Arab-identified pastoralists since the outbreak of war in Darfur in 2003, and has intensified in the past decade due to the increased paramilitarization of western Sudan. Elites from these groups do not value the elaborate hierarchies of interests in Khartoum, and are no longer beholden to them (Rift Valley Institute, 2019). Backed by Saudi Arabia and the UAE, Hemedti is thus a deeply destabilizing element in the transitional government, with no clear checks on his behavior by the political or military establishment of Khartoum.

The relationship between these two constellations of armed power within the counter-revolutionary bloc will ultimately determine the broad trajectory Sudan takes over the coming decade. By extension, they will determine where violence will take place, and the intensity of this violence. The three likeliest scenarios stemming from this relationship are: first, war among the security apparatus; second, collusion among these same actors to perpetuate a similar system to the one they overthrew; and third, a deliberate and phased decentralization of power and wealth from Khartoum to the peripheries.

In the first and third scenarios, a decentralization of power from Khartoum occurs through different means and to different ends. War among the security organs represents a destructive and unpredictable re-division of power, whilst a calculated decentralization represents a more orderly response to the mounting challenges. These challenges–brought about by Sudan’s status as a post-oil state and the emboldening of paramilitary forces from the semi-periphery– undermine the ability of the Khartoum establishment to rule the country effectively. Collusion between the military establishment and paramilitary elites represents a ‘holding pattern’ which reproduces the current accommodation between military elites, though one which is likely to perpetuate the underlying conditions of Sudan’s crisis.

In the first scenario, conflict tears apart the security apparatus, taking the country into civil war. Were Sudan to descend into civil war, violence would be widespread and almost certainly drag neighboring countries into the fray, and likely Gulf powers. It would begin as a consequence of covert maneuvers among the security organs of Sudan, and would be sparked by a coup or failed coup by the security establishment against Hemedti, or vice-versa.

Outright war among the security establishment of the country has never occurred, and unrest has instead been confined to peripheral units who have mutinied in response to unwelcome national developments. However, the military structure has evolved under Bashir into a panoply of security organs of differing loyalties and sometimes overlapping functions. Although factionalism may persist within these components, there is now a wider factionalization between different branches of the security apparatus, each linked to distinct domestic and external constituencies. Were a showdown to occur between the RSF and the SAF, the military balance would shift towards the power bloc that has been able to pre-emptively build a coalition of either loyal or tactical partners, whilst seeking financing from the Gulf. Hemedti’s recent activity in various peace forums inside and outside of Sudan should be watched closely in this regard, as these provide excellent opportunities to reorient power in his favor. It should be noted that the RSF – much like other parts of the security apparatus – is not a unified entity, and rivalry among RSF commanders could be an additional source of instability and violence, particularly in the event of a prolonged war (de Waal, 2019: p.22).

In the event of a military stalemate, hostilities could not be sustained at a national-scale indefinitely. This is due to the absence of resources of a sufficient value that can also be centralized and directed to the national war effort. Had South Sudan remained an autonomous part of Sudan instead of seceding then things may have been different, with oil revenues being used to finance the conflict (see figure below). After the loss of three-quarters of Sudan’s oil reserves, the only other resource that could substitute for oil is gold. Gold is dispersed across most of Sudan, and the system for selling gold has more moving parts than the oil system does, requiring engagement with warlords in some areas and artisanal miners in others (de Waal, 2019: pp.13-14). The value of the gold extracted would vary depending upon whether it was smuggled out of the country (incurring additional costs) or sold directly to an international buyer for hard currency. In the absence of a diversified war economy with easily taxable resources, the fragmented security system would either have to reunite under a peace agreement, or maintain the interest of Gulf states to consolidate as much strategic and resource-rich territory as possible. However, it is not clear how the interests of Gulf states or Sudan’s neighbors would be served by a destructive and lengthy civil war (as discussed further in the forthcoming final analysis piece in this series), though it would certainly be of benefit to rebel groups and anti-government factions both in Sudan and in the Horn of Africa.

Sudan’s oil exports, 1999 to present, thousands of barrels per day

The second scenario involves a strategic (rather than merely tactical) accommodation by enough of the security system to collude in jointly managing the country for the foreseeable future, and avoid widespread conflict. This would represent a continuation of a military-dominated system, with power now being shared between military, paramilitary, and certain rebel elites. As such, it would modify, but not overhaul, the extractive and exploitative core-periphery dynamic embedded in Sudan’s political economy. Under this scenario, violence is once again displaced back to the peripheries, but is limited to the goals of capturing resources (particularly gold mines) and trade routes on the part of armed elites, and to managing clashes between smaller paramilitary factions and rebel groups. Although this would result in increasing predation and militia recruitment in select parts of the periphery, it would not threaten the core (see Thomas and El Gizouli, 2020: p.5; Sudan Democracy First Group, 2017: p.53). Concurrently, the security apparatus would continue to control much of Sudan’s industrial infrastructure (including the Military Industrial Corporation operated by SAF, see Small Arms Survey, 2014), with RSF and SAF elites continuing their efforts to divide up the business empire previously run by NISS (see Gallopin, 2020). Holdout rebels under Abdedaziz al-Hilu would continue to remain at arm’s length from the government, whilst Sudan Liberation Movement/Army rebels under Abdul Wahid al-Nur would dig-in to Jebel Marrah.

The difficulty with this scenario is that it essentially returns the country to the same predicament it was in the year prior to the removal of Bashir, with elites from the armed forces, paramilitary and rebel groups simply cutting out party officials, intelligence chiefs, and bureaucrats from the proceeds of the nexus of military spending and crony capitalism. Such a continuation would almost certainly renew cycles of civil unrest and harsh repression, rather than addressing the deep structural challenges that accompany a decarbonization of an oil-dominated economy. Crucially, it would also require paying for the vast security apparatus, which consumed close to 70% of Sudan’s publicly disclosed budget under Bashir (in addition to off-budget security spending) and would force security and military elites to continually seeks ways of remortgaging the country to external powers in the absence of sufficient resources in the country to keep the system afloat. As Thomas and el Gizouli summarize:

“[It] is not possible for the government to spend its way out of its inherited crises, which are reproduced on a daily basis by Sudan’s systems of wealth generation. Sudan’s wealth is produced in a way that serves the interests of a relatively small group of politically well-connected people, extracting economic benefits from the country’s vast spatial inequalities. Replacing peripheral exploitation with peripheral investment in less grueling, less violent production systems needs a radical reconsideration of the whole economy… Without a radical reconsideration of Sudan’s economic direction, the new government will need to woo its donors—the military corporations, the Gulf palaces, the international financial institutions—and allow their priorities to dislodge those of the revolutionaries.” (Thomas and el Gizouli, 2020: p.6)

This leads to the final scenario, in which the Sudanese military elites face up to the reality that the hyper-concentration of political and economic power in Khartoum has been to the collective detriment of almost all Sudanese, and no longer represents a viable basis for organizing power and wealth. The vast military apparatus required to enforce this concentration has become an unsustainable and dangerous liability for the country in the absence of sufficient oil wealth, and an economy premised on plunder and cutting deals with provincial elites cannot support this system. A planned decentralization of wealth and resources away from the center – calibrated towards a gradual demilitarization of society – would be the ideal solution to this set of problems.

If the counter-revolutionary elite decide to consolidate their current accommodation (as outlined in the collusion scenario), there is a good chance the system will eventually tip over into the war or planned decentralization scenarios. In contrast to a trajectory of war, a calculated and orderly decentralization and a phased redistribution of power and wealth to the peripheries would help to stabilize Sudan’s political economy. As with many violent political systems in which patronage is a central organizing principle, both unexpected surges of wealth as well as sudden contractions in the amount of wealth or value of resources tend to drive rounds of violence, whilst warping the growth of military and security institutions, who must continually adapt to this financial and political volatility.

Sudan exemplifies such a volatile system, and looks set to drift into a prolonged phase of austerity which will concentrate fighting around remaining sources of wealth. If the state is to endure and be of some benefit to its population, overhauling this system and its perverse incentives is an imperative. Given the deeply ingrained legacies of ethnic discrimination, elite accumulation, and the fortification of the Khartoum elite through military and paramilitary expansion, this is the least likely scenario in the short term. To carefully replace centralized and militarized rule – and to redistribute wealth and infrastructure – would require a recalculation of elite interests and a difficult change in mentality. It would also require substantial international pressure, as well as generous assistance. Yet such a shift could quell the increasing urban ethnicized conflicts that are ripping through the country (and being propelled by political and economic instability and uncertainty), while a socialized safety net could be financed from the existing industrial and commercial infrastructure operated by security elites. Whilst the decentralization and eventual demilitarization sought by many Sudanese for generations is unlikely to materialize in the near term, a military system which has exhausted the country’s resources and patience may have to give way to a more sustainable system, or risk consuming itself in the process.

Conclusion

The unrest and violence in Sudan’s core is the delayed response to a crisis brought about by the secession of South Sudan, and which has been exacerbated by a reflex on the part of the security elite to address threats to Khartoum’s dominance through empowering paramilitary forces. This approach has backfired, resulting in a crisis in Khartoum that now threatens to ripple across Sudan’s troubled peripheries and potentially the wider region. The fate of the country is largely in the hands of a fractious elite, acting in desperate circumstances.

Sudan (and soon, South Sudan) will become an early example of the consequences that accompany rapid decarbonization in a society wracked by intense militarization and war (see Mitchell, 2013; Selby, 2020), which are themselves closely linked to the acquisition of wealth and resources. Sudan may however be able to map a route out of this dilemma, though this would require a difficult shift in mentality away from the short-term crisis management and reckless accumulation ingrained in the culture of Sudan’s armed elites. This would need to be replaced by developing a more sustainable approach rooted in long-term planning and redistribution of wealth and capital, and through decoupling dignity and power from employment in the security organs.

How Sudan’s leaders respond to the crisis will provide clues as to how similar regimes adapt to global price volatilities and transitions away from fossil fuels in war-torn societies. Early signs are not encouraging. Military and paramilitary elites are scrambling for control of economic resources in Khartoum, as violence spreads in the core and the peripheries. In addition to their domestic agendas, these elites are casting their sails to the winds sweeping through the Horn of Africa from the Gulf, which will have a strong influence on the direction that Sudan takes over the coming years. In the final analysis piece of this series, Sudan’s turbulence will be situated within the broader reconfiguring of relations within the Horn, and to international power beyond.

Part of the author’s time was supported by the European Union’s Horizon H2020 European Research Council grant no: 726504

Appendix: List of Major Security Organs in Sudan3Sources: ACLED data; The Arab Weekly, 19 May 2020; Assil, 2019; Berridge, 2013a; Berridge, 2013b; El-Battahani, 2016; HRW, 1994; International Crisis Group, 2013; Radio Dabanga, 23 December 2019; Small Arms Survey, 2011; UNSC Panel of Experts, 2017; de Waal, 2017; de Waal, 2019

Below are listed the major security organs (both regular and irregular) active at the end of the NCP-era, with information on their current status provided where possible.

| Border Intelligence Brigade (a.k.a. Border Guards) | Established in 2003 in Darfur. Primarily built around irregular militias of the Mahamid clan of the Rizeigat, who operated under the control of notorious Janjaweed leader Musa Hilal (in prison since late 2017) in northern Darfur. This was in an attempt by the Bashir regime to partially formalize and regulate militia activity. Border Guards were active in counterinsurgency in Darfur, and were also embroiled in the proxy war between Sudan and Chad. Musa Hilal and the other Border Guard commanders active in areas further south of Hilal reported to SAF Military Intelligence. After counterinsurgency operations in Darfur subsided in 2007, tensions emerged between Musa Hilal and Khartoum, whilst rivalries between commanders weakened the group. The gold boom of the early 2010s intensified violence between factions, with Hemedti and the RSF prevailing. The Border Guards exist today, though activity has declined substantially. |

| Central Reserve Police (a.k.a. Abu Tira) | Paramilitary gendarmerie active during the war in Darfur and linked to violence in South Kordofan. The precise date of establishment is unclear, though they appear to have been active since at least 2004, and are reported to have been under the control of SAF during the 2000s. They are infrequently active in recent years. Their relationship to other regular security organs is unclear. |

| Irregular paramilitary groups | The Sudanese state has been linked to numerous paramilitary groups during its wars in Southern Sudan, Darfur, and the ‘Two Areas,’ though only some of these groups have enjoyed a semi-regularized status, and fewer still have received regular salaries. These groups were often drawn from Arab-identified Baggara and Rizeigat pastoralist groups of the semi-periphery, and Southern Sudanese paramilitary and self-defense groups hostile to the dominant Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army rebellion during various stages of the 1983-2005 war. Whilst NISS and Military Intelligence have maintained contact with many of these forces or their remnants, they no longer retain close operational or logistical relationships with the majority of such groups. |

| National Congress Party (NCP) militias | Details about NCP militias are vague. Senior elites of the NCP were long rumored to have maintained private militia forces as well as possible connections to Popular Defence Force units, whilst ‘shadow battalions’ of men in civilian clothing working alongside NISS forces to detain and abuse demonstrators during the 2018/19 uprising are likely to be connected to the NCP. Additionally, details on an unspecified “Martyrs’ Organization” were found in the accounts of the Popular Defence Forces after the fall of Bashir. Activity by NCP militias has all but ceased after mid-2019. |

| National Intelligence and Security Services (NISS) | An intelligence service which succeeded the State Security Organization (established in 1978), and which became an early praetorian guard to the Bashir regime. By the secession of South Sudan in 2011, NISS was regarded as an indispensable but potentially disloyal element of the security apparatus. It was rebranded as the General Intelligence Services (GIS) in July 2019, with former NISS director Salah ‘Gosh’ reported to have fled the country. GIS will be smaller than NISS, with a more explicit focus on intelligence than policing and military operations, with much of the Operations Division in a contested process of demobilization. It is unclear whether its ethnic composition (drawn predominantly from the riverain areas of the center and north of Sudan) will be diversified. |

| Paramilitary police forces | Bashir established a range of paramilitary police forces, often linked to the Islamist project. These include a Popular Police Force and the Public Order Police, which were formed in 1992 to uphold the Public Order Law of the same year. An additional Society Police was established in 2002 to uphold the Morality and Social Guidance Law of 2000, and then integrated into the Public Order Police in 2008. These units are presumed to have been disbanded after the 2019 coup, with no recorded activity. |

| Popular Defence Forces (PDF) | Islamist militia established shortly after the coup by Bashir, and disbanded in June 2020. The PDF were linked to numerous military operations and abuses in South Kordofan and Darfur, with reports of Sudanese from marginal areas (notably the East) being forcibly conscripted for both counter-insurgency purposes and during tensions with Eritrea. Although informally organized, they would follow orders from SAF commanders during military operations. |

| Rapid Support Forces (RSF) | Established in 2013, growing out of a faction of the Border Guards led by Hemedti, and dominated by members of the Mahariya branch of the Rizeigat. Initially controlled by NISS before becoming an autonomous force (nominally integrated with SAF) to provide regime security, and conduct counterinsurgency operations in peripheral areas of Sudan. Efforts have since been made to diversify the ethnic base of the RSF, bringing in non-Arab groups. The RSF was also leased to foreign governments. Estimates as to the size of the RSF range from 20-40,000, with RSF soldiers reportedly better and more reliably paid than the regular military. The rising power of the Hemedti’s paramilitaries since the early 2010s has generated increasing concern in the regular army, though El Burhan has made speeches recognizing a legitimate role for the RSF in the post-Bashir era. The RSF has close links to the UAE via Hemedti. |

| Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) | Official military established in the 1920s under Anglo-Egyptian rule of Sudan. Retains close links to Egypt. After independence in 1956, the army acquired a reputation as a dedicated and professional force, albeit one which saw itself above civilian politicians, and whose composition reflected the ethnic hierarchies of Sudan. Elements of the army have engaged in coups to remove civilian governments in 1958, 1969, 1971, and 1989, and to remove military governments during civilian-led uprisings in 1964, 1985, and 2019. Under Presidents Nimeiri and Bashir, the military was regarded as a threat and gradually degraded in capacity; and tethered to regime rather than national security; and with senior officers incentivized to engage in business ventures. Since the early 1980s, SAF has gradually accepted the transfer of violence and risk to paramilitary units to the distress of retired generals of the army. Despite these problems, the army remains the largest entity in the security apparatus. |

| SAF Military Intelligence | The Military Intelligence service of the Sudan Armed Forces has a considerable degree of independence from the regular army, and has been active in communications and support with irregular paramilitaries forces during wars in the peripheries, particularly in Southern Sudan and Darfur. |