By the Numbers: Cabo Delgado, October 2017-December 20201Figures updated as of 5 December 2020.

- Total number of organized violence events: 711

- Total number of reported fatalities from organized violence: 2,426

- Total number of reported fatalities from civilian targeting: 1,226

All ACLED data are available for download via the data export tool, and a curated Mozambique dataset is available on the Cabo Ligado home page.

Situation Summary

The conflict in Cabo Delgado experienced a lull last week, with the only shooting reported during a friendly fire incident between government forces and a local militia in Macomia district. On 2 December, according to a source who wrote in to Pinnacle News, militia members ambushed a government patrol believing it to be a band of insurgents. Soldiers were killed in the ambush, but it is not clear how many.

More information has come to light about earlier incidents, including a deadly insurgent ambush on 29 November. Insurgents attacked government soldiers patrolling in the woods near Matambalale, Muidumbe district, killing 25 and injuring 15. Among those killed were a colonel and a major in the army. The government patrol was in response to insurgent activity in the nearby villages of 24 de Março, Nanhoka, Ingundi, and Muambula between 26 and 29 November, during which insurgents burned homes and killed civilians. The number of civilian deaths is not known. It is notable that soldiers, and not police, were the victims of the 29 November ambush, since it was the police who had so publicly taken the lead in the government counteroffensive in Muidumbe just weeks ago.

Pinnacle News also obtained photographs of the aftermath of a previously unreported insurgent raid on a maternity hospital on Ilha Matemo, Ibo district on an unspecified date in early November. The insurgents stole medicine and left graffiti on the walls. Government security forces reportedly killed seven insurgents before they could leave the hospital.

There were also further reports of abuses against civilians by Mozambican security forces. On 27 November, an accidental discharge of what appears to have been a mortar injured two adults and a child in Palma when the shell exploded in a residential area near a hotel.

In Ibo district, a government motorboat has been intercepting boats carrying refugees and goods between Pemba and northern Cabo Delgado, ostensibly to verify that the travelers are not associated with the insurgency. The security service members, however, have been demanding illicit payoffs from passengers in order to be allowed to pass.

There have also been reports of looting in areas of Muidumbe district that civilians have recently evacuated. The looters’ identities are not clear. They had struck at least 10 homes, a secondary school, and a community radio station in Muambula by 1 December. Looting reports have been frequent during the conflict, as mass displacement creates many unguarded homes.

Incident Focus: Aid Needs and Distribution

The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) released its Global Humanitarian Overview last week, which included its projections for humanitarian needs in Mozambique in 2021. Many of the numbers quoted to describe the humanitarian disaster in Cabo Delgado are familiar — over 500,000 people displaced and 900,000 threatened with high levels of food insecurity — but the projections of funding needs are new and concerning. OCHA estimates that it will need $254.4 million to serve 1.1 million people in need in Mozambique in 2021. That represents a seven-fold increase over this year’s international funding request of $35.5 million for Cabo Delgado. According to OCHA’s most recent situation report, even that modest request has only been 65% funded. With major international donors still battling the COVID-19 pandemic and its economic effects, it remains unclear how much money will be available to support vulnerable people in northern Mozambique.

Even if aid does come to Mozambique, people living in the conflict zone will still have to leave their homes behind to receive it. Cabo Delgado secretary of state Armindo Ngunga told state media that the government will not send aid directly into areas where there is violence, both for the safety of the aid providers and to prevent supplies from falling into insurgent hands. The policy is an acknowledgement of the government’s inability to protect humanitarian workers in the conflict zone, and it puts civilians remaining in the conflict zone in a bind. A lack of supplies entering the conflict zone forces civilians to abandon their homes to avoid starvation and incentivizes insurgents to expand their operational area in search of supply sources to loot. Civilians, in other words, cannot remain within the conflict zone, but also will be more subject to insurgent attack at the edges of the contested area.

Further complicating matters for displaced civilians, a new report by the Mozambican civil society organization Center for Democracy and Development (CDD) alleges that the Northern Integrated Development Agency (ADIN) has been slow in taking on its responsibility to serve displaced people in the northern provinces. Despite launching four months ago with the aim of centralizing development and humanitarian efforts in Cabo Delgado and the surrounding provinces, the agency still has not completed a strategic plan, much less been active on the front lines of Cabo Delgado’s humanitarian crisis. CDD researchers spoke to displaced people in Pemba and Montepuez who had never heard of ADIN. In all, it is unclear how the resources and processes necessary to serve Cabo Delgado civilians will be able to come together in the new year.

Government Response

Mozambican police chief Bernardino Rafael last week encouraged civilians displaced by fighting in Quissanga district to once again attempt to return to their homes. An estimated 45,000 people fled intense fighting in the district in March, and some returned after a period of calm followed a May government counteroffensive to retake the district. Quissanga seemed like a government success story for months until insurgents reappeared in September, killing at least 10 civilians with no substantial government response. The epicenter of violence has once again shifted away from Quissanga, but it is unclear if government forces can provide any greater security than they did in September. Without clear evidence that government troops can protect them, Quissanga residents may be unwilling to attempt another return home.

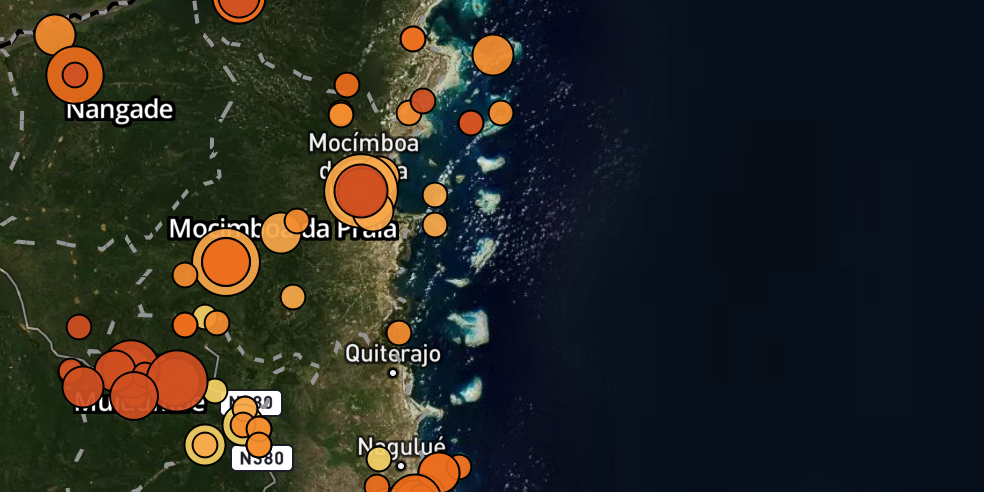

One method for augmenting the state’s security apparatus in Quissanga district would be to take a page from reported efforts in Muidumbe, Macomia, and Palma districts and organize local militias there. Local militias have become a more prominent tool in the government’s arsenal in recent months, which is a double edged sword for the government. On one hand, the militias offer valuable assistance to government forces in defensive and, occasionally, offensive operations against the insurgency. On the other hand, the militias can become political actors in their own right. Signs of the latter were apparent last week as Fernando Faustino, head of the Association of Veterans of the National Liberation Struggle, called for the government to better support war veterans involved in local militias in Cabo Delgado. Faustino hailed the veterans as an effective fighting force, claiming they have been active in Nangade, Macomia, Palma, Mocimboa da Praia, and Muidumbe districts. Those claims may be an exaggeration, but war veterans were certainly involved in recent police operations in Muidumbe district.

Help should also soon be easier to come by for humanitarian organizations. The government has created a special visa category for aid workers arriving during Mozambique’s declared state of public disaster, making it easier for humanitarians to enter the country. Humanitarian groups had complained that their employees were having a difficult time getting into Mozambique. The state of public disaster refers to the COVID-19 pandemic, however, so it is unclear whether the visa will remain in place once the virus is under control.

On the international front, US counterterrorism coordinator Nathan Sales met with Mozambican president Filipe Nyusi and members of his cabinet in Maputo last week. In a readout of the call, Sales said that “the United States wants to be Mozambique’s security partner of choice” for confronting ISIS-associated insurgents, but was clear that his focus was on increasing Mozambique’s civilian counterterrorism capacity rather than any sort of military cooperation. No details on counterterrorism cooperation were agreed to during the trip, Sales confirmed. The US embassy press release covering the meeting emphasized the $42 million in funding the US has pledged for humanitarian and development projects in Cabo Delgado, as well as its support for ADIN.

The Portuguese government announced that it is sending a delegation to Mozambique this week to discuss the terms of a promised aid package from the European Union aimed at boosting Mozambique’s counterinsurgency effort. Portugal’s ambassador to Mozambique told reporters that the EU is still waiting on a list of specific requests from the Mozambican government as to what it would like the aid package to include, but said she is confident that the Portuguese delegation will receive such a request during its visit.

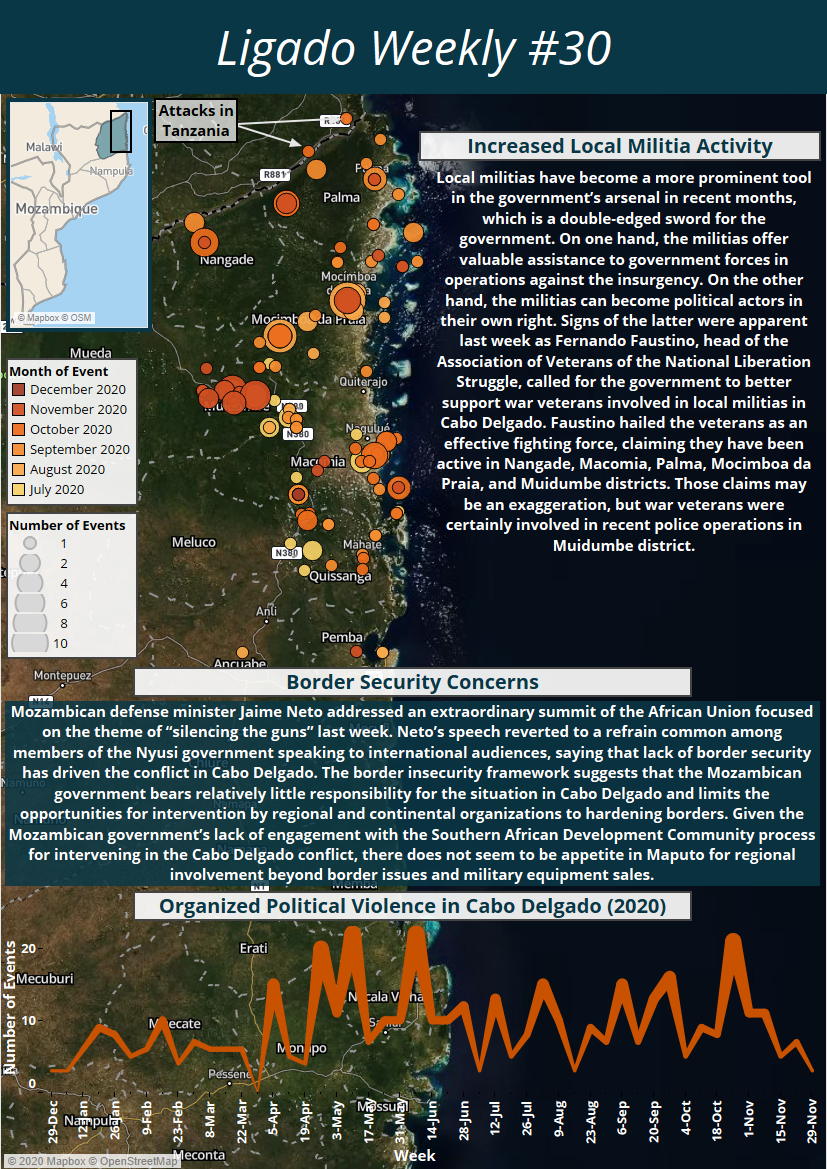

Mozambican defense minister Jaime Neto addressed an extraordinary summit of the African Union focused on the theme of “silencing the guns” last week. Neto’s speech reverted to a refrain common among members of the Nyusi government speaking to international audiences, saying that lack of border security has driven the conflict in Cabo Delgado. The border insecurity framework suggests that the Mozambican government bears relatively little responsibility for the situation in Cabo Delgado and limits the opportunities for intervention by regional and continental organizations to hardening borders. Given the Mozambican government’s lack of engagement with the Southern African Development Community process for intervening in the Cabo Delgado conflict, there are concerns among some regional observers that there does not seem to be appetite in Maputo for regional involvement beyond border issues.

Increased Local Militia Activity

Local militias have become a more prominent tool in the government’s arsenal in recent months, which is a double edged sword for the government. On one hand, the militias offer valuable assistance to government forces in operations against the insurgency. On the other hand, the militias can become political actors in their own right. Signs of the latter were apparent last week as Fernando Faustino, head of the Association of Veterans of the National Liberation Struggle, called for the government to better support war veterans involved in local militias in Cabo Delgado. Faustino hailed the veterans as an effective fighting force, claiming they have been active in Nangade, Macomia, Palma, Mocimboa da Praia, and Muidumbe districts. Those claims may be an exaggeration, but war veterans were certainly involved in recent police operations in Muidumbe district.

Border Security Concerns

Mozambican defense minister Jaime Neto addressed an extraordinary summit of the African Union focused on the theme of “silencing the guns” last week. Neto’s speech reverted to a refrain common among members of the Nyusi government speaking to international audiences, saying that lack of border security has driven the conflict in Cabo Delgado. The border insecurity framework suggests that the Mozambican government bears relatively little responsibility for the situation in Cabo Delgado and limits the opportunities for intervention by regional and continental organizations to hardening borders. Given the Mozambican government’s lack of engagement with the Southern African Development Community process for intervening in the Cabo Delgado conflict, there does not seem to be appetite in Maputo for regional involvement beyond border issues and military equipment sales.