This is the final part in a series of three analysis features covering unrest in Sudan. The first in the series — Riders on the Storm — explored the dynamics and agendas which resulted in the Juba Peace Agreement. The second — Danse Macabre — examined the origins of the uprising in Sudan and its trajectory following the coup of April 2019. This final analysis situates Sudan’s current upheaval in the context of the Horn of Africa, and extends the scope of analysis to encompass conflict in Ethiopia and the region.

Introduction

Since 2018, the Horn of Africa has made headlines for a series of dramatic developments. Following years of protests in the restive Oromia region, a power transition took place in Ethiopia in April 2018. In December of that year, anti-government demonstrations began in Sudan. This culminated in a coup in April 2019 which was greenlit by Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) (Gallopin, 2020). A dubious peace deal was reached in South Sudan in September of 2018 at the insistence of Sudan and Uganda, months after Saudi Arabia and the UAE brokered a peace agreement in Ethiopia and Eritrea in July (see Woldemariam, 2018; Watson, 2019).

Events in the Horn have not proceeded entirely smoothly since these changes, despite initial optimism that a more pluralistic form of politics led by civilians would take root in Sudan and Ethiopia. Sudan’s military and paramilitary forces have cast an increasingly long shadow over the supposed transition underway in the country, while growing tensions between Ethiopia’s new administration and its former rulers — the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) — led to fears of civil war, as disorder spread to several parts of the country (see International Crisis Group, 2020a).

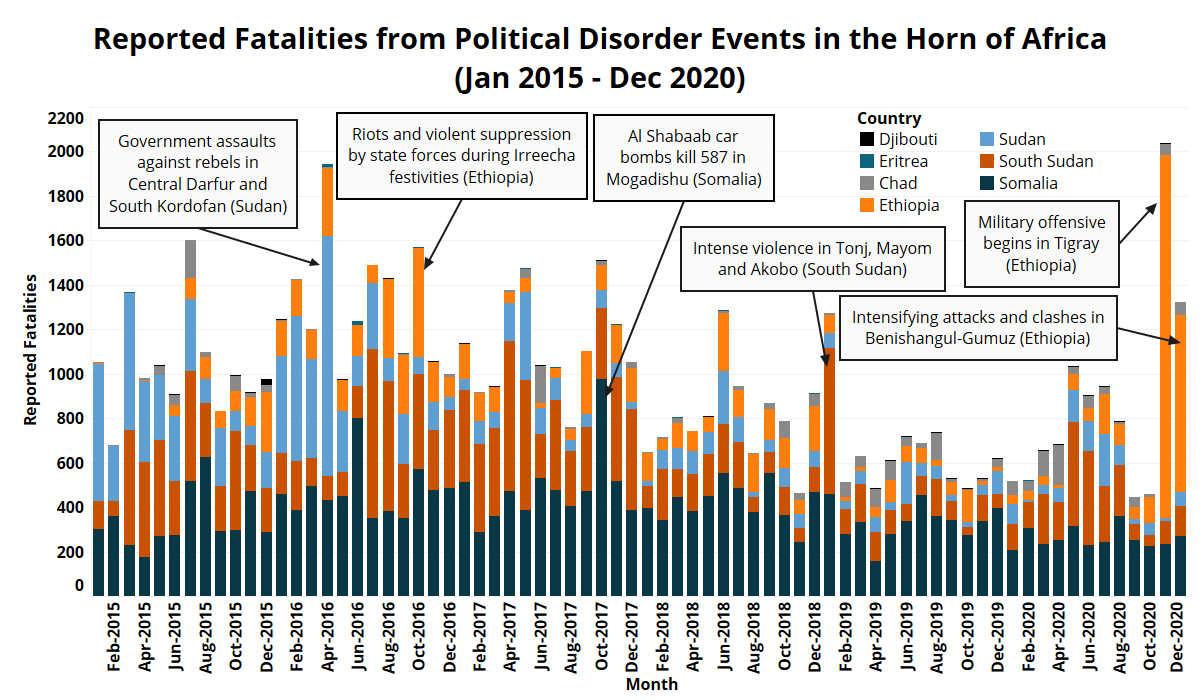

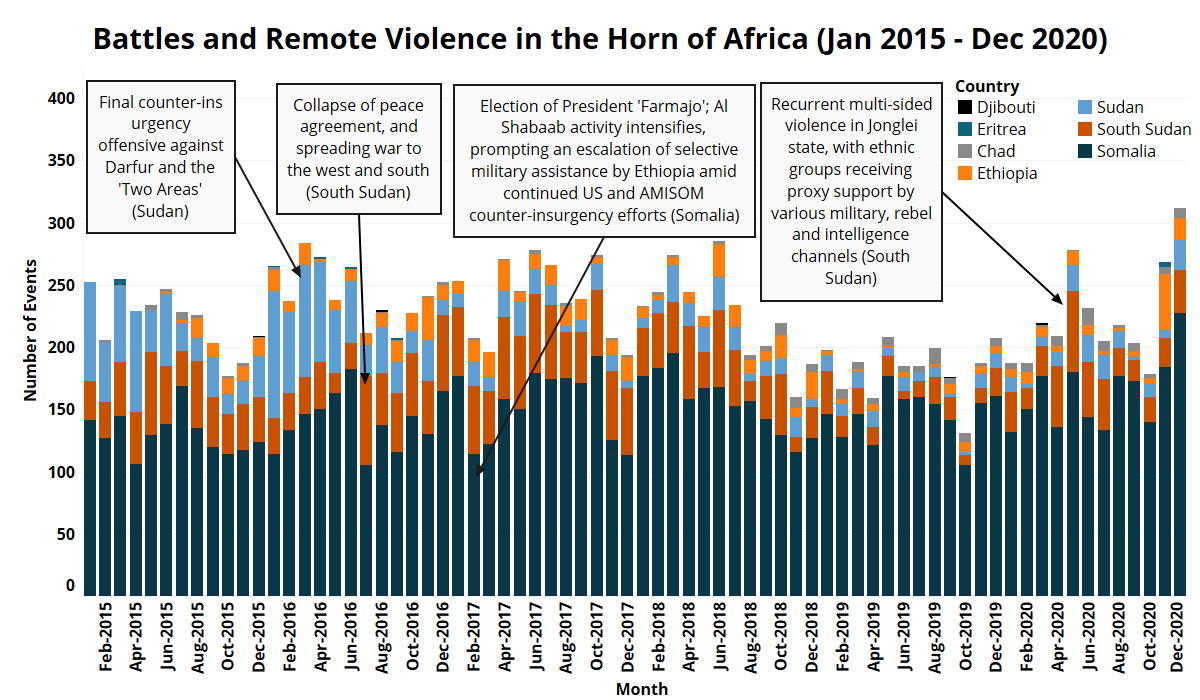

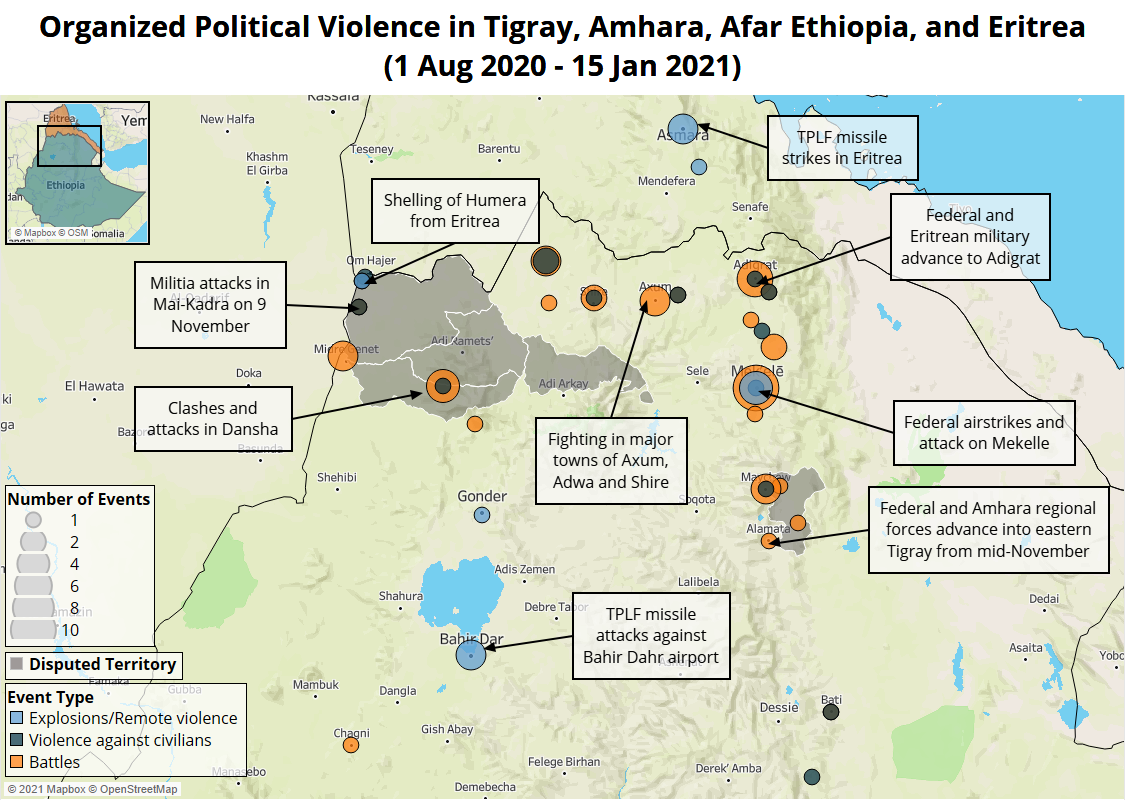

Things escalated further on 4 November 2020, when Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed declared “the last red line has been crossed” after soldiers of the TPLF attacked a number of federal military bases the previous evening. The Prime Minister ordered federal soldiers alongside forces from the Amhara region to remove the TPLF leadership and dismantle the political and security infrastructure of the former ruling force in Ethiopian politics. The events have sparked alarm as contending military forces — including forces from Eritrea — have plunged the northern region of Tigray into war. The war in Tigray, together with escalating violence in Benishangul-Gumuz, has resulted in soaring fatalities in the Horn, following an unsteady decline in recent years (see figure below).

This was the latest in a string of decisive moves by Abiy since his ascension to power in April 2018, including the signing of a peace agreement with Eritrea in July of that year and the dismantling of the party system (introduced by the TPLF) in December 2019. A common pattern has been for a solution to one problem to lay the foundation for the next (often more serious) problem.

There are red lines of a different sort in the Horn of Africa, too. Once a region notorious for intersecting internal and external wars, the potential for violence along and across its often marginalized and sometimes contested border regions had gradually abated in recent decades. Violence has instead become concentrated within restive enclaves within countries (some of which remain close to regional flashpoints), and most regimes in the Horn have increasingly refrained from exploiting such conflicts to destabilize neighboring regimes. Instead, regimes have entered into partnerships for mutual security, and to limit exposure to flashes of volatility.

Since the war in Tigray broke out, a proliferating number of theories outlining an emerging regional war (with external involvement) have been advanced by analysts and pundits. The war in Tigray, and escalating clashes in a disputed area of the Sudan-Ethiopia border, have formed the starting point for such claims. This analysis engages with this discussion by taking a different approach, based on assessing the cross-border dynamics and interests in critical areas of the Horn, to consider whether a spreading regional conflagration is indeed a likely outcome of the current fighting.

Ethiopia sits – along with Sudan – at the core of the military-political system which underpins the regional order in the Horn of Africa. Sudan and Ethiopia are akin to a set of gears turning: when they are turning in unison, then regional stability is upheld, but when they grind in different directions then cross-border and sometimes regional turbulence can follow. The two countries had particularly close links under their former regimes, despite stark ideological differences and serious tensions during the mid-1990s (Young, 2020). These links are weaker today, and the working relationship between Khartoum and Addis Ababa is strained by disagreements over the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), a border dispute in eastern Sudan, and rebuffed efforts by the Sudanese Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdock to mediate between the TPLF and the Ethiopian federal government.

The degree of volatility in the Horn indeed appears higher than at any time in recent years. Yet there is a pressing need to identify whether there is indeed validity to fears of an all-out regional conflagration, and whether the faultlines beneath the current upsurge in violence actually run through the entirety of the Horn. The trend since the early-2000s has been for insurgencies and military interventions to spark vicious sub-regional wars (as with Darfur and Chad, and the Ethiopian-Eritrean proxy war in Somalia) instead of the large multi-sided wars of the 1980s and 1990s. Further, the implosion of South Sudan in 2013 was followed by a degree of regional support (albeit qualified and calculated in nature) to the beleaguered government, which formed the basis of an eventual rapprochement between Sudan and Uganda after decades of tensions.

This analysis begins by summarizing some of the central developments in the Horn in recent decades, arguing that a gradual shift from subverting to supporting neighboring regimes has been underway in regional geopolitics. Rather than seeking to undermine one another, the regimes of the Horn have increasingly tended to support one another, with some exceptions. This partly explains the remarkable longevity of some of the Horn’s regimes, in spite of intermittent crises. With the exception of Somalia — where regime change has previously occurred due to regional meddling and implicit term limits placed on its presidents — changes in the rulers of the day are now instigated by elites in the upper echelons of the dominant party or security organs during times of national unrest. Overall, this section observes how the regimes of the Horn have invested heavily in one another’s survival, even if they retain significant capacity to intensify violence in restive areas should they feel pressured to do so.

The remainder of the analysis takes the form of a series of case studies exploring dynamics of stability and instability in some of the major border regions of the Horn. The first set of studies considers the effects of instability in Sudan upon its neighbors, and the second set shifts the focus to the consequences of escalating tensions in Ethiopia for nearby countries. This begins with accounts of the dynamics in the Sudan-Ethiopia border (focusing on the recent fighting in the El Fashaga triangle) before analyzing political and security developments in the Sudan-Chad and Sudan-South Sudan borderlands. Next, the South Sudan-Ethiopia and Somalia-Ethiopia border regions are discussed, before concluding with an overview of available information on Eritrea’s apparent resurgence in northern areas of the Horn.

These case studies help nuance the discussion of the trends in the Horn of Africa, by noting growing dependency on the regional hegemons of Ethiopia and Sudan by their weaker neighbors. In the case of South Sudan, this has resulted in Juba calibrating parts of its security and economic systems with those of Khartoum. With the important exception of Eritrea, weaker countries of the Horn entered into close arrangements with more powerful countries to limit their own exposure to instability and regime change.These countries have a vested interest in containing the spread of conflict between Ethiopia and Sudan. Whether they will be effective in doing so remains to be seen. Efforts to contain instability may also be undermined by Eritrea’s actions, which do not show the same degree of concern for regional stability. This nevertheless suggests greater consideration ought to be given to specific interests, agendas, and limitations when mapping out potential routes that a regionalized conflict might take.There is a need to recognize the presence of political forces and connections that work against conflict spreading in the region.

The war in Tigray and in disputed areas in the Sudan-Ethiopia border are deeply concerning for a variety of reasons, not least of all because the principal actors have not shown the same degree of hesitance when it comes to escalating events. For the time being, they are separate conflicts, and treating them as an embryonic regional war is premature. Were these conflicts to escalate and/or merge, this would carry risks to Sudan and Eritrea, who would also struggle to sustain lengthy military operations without external assistance. Ethiopia would face difficult choices in allocating its forces amid spreading insecurity, and all belligerents may have to contend with a new US administration that is unlikely to be as relaxed as the Trump administration with regards to permitting military actors to project force across borders in the Horn.

Despite originally intending in this series to focus on the role of Gulf actors in Sudan and their impact on the broader politics of the Horn, this analysis deliberately keeps geopolitical speculation involving Gulf states to a minimum.1 Excellent accounts of Sudan’s recent foreign policy entanglements can be found in Gallopin, 2020, Manek and Gallopin, 2020a, and Sørbø, 2020. This is partly to keep the focus on the specific dynamics within and between the countries of the Horn, but also because the fast-moving developments across both sides of the Red Sea preclude a sound analysis from being advanced at the current time. The grudging rapprochement between Qatar and the fraying alliance of Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Egypt (see Ulrichsen, 2020; The Economist, 10 December 2020) is likely to have varied and unpredictable consequences for both the Horn as well as for internationalized conflicts in Libya and Yemen. The lopsided interactions between the Gulf and the Horn have had important implications for the Horn (see de Waal, 2019a; de Waal, 2020a; Vertin, 2019), though the after-effects of recent realignments in these relations may take some time to emerge.

Regional Politics: From Antagonism to Accommodation

The Horn of Africa has for decades enjoyed an unenviable reputation as being among the most violent and politically unstable corners of Africa. Part of the reason for this is the tendency for regional politics to compound domestic disorder and insurgency. Other reasons include external meddling from international powers, and bitter disputes over where political boundaries should be drawn after decolonization.

During the latter stages of the Cold War and much of the 1990s, the Horn of Africa became notorious for the destructive role of mutual destabilization activities (Cliffe, 1999; de Waal, 2004: Ch. 6). This typically involved regimes undermining the stability of one another by providing various forms of support to rebel groups attempting to overthrow governments in neighboring countries. During the 1970s and 1980s, these dynamics interacted with Cold War geopolitics, with regimes in the Horn attempting to manipulate the flows of weapons and financial resources by superpowers, who in turn hoped to deny strategic locations in the Horn to the rival superpower.

This reached an extreme point during the late 1990s, when a military alliance against Khartoum brought forces from Ethiopia, Eritrea, and Uganda into parts of Sudan to assist Southern Sudanese rebels from the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army (SPLM/A). The government in Khartoum may well have collapsed under the pressure were it not for the outbreak of the Ethiopia-Eritrea war in 1998 (which caused the two warring nations to disengage from wars in Sudan and improve ties with Khartoum), and the distraction caused by Uganda’s misadventures in what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo in the late 1990s (de Waal, 2015: 47-49).

Since then, there has been a gradual warming of relations among the countries of the Horn, with the important exception of Eritrea. In recent decades, a regional consensus has emerged which has for the most part reversed policies of mutual destabilization towards one of mutual stabilization. Most governments have increasingly become invested in each other’s stability, and have largely desisted from engaging in activities which would return the region to rounds of regional war of the 1980s and 1990s.

At the core of this change has been the partnership between the Sudanese government under Omar al Bashir and Ethiopia under the TPLF since the late 1990s (Young, 2020). Sudan and Ethiopia have long been at the core of fractious politics of the region, and the significant reduction in cross-border attacks and arming of rebel groups in the western half of the Horn is in large part attributable to the effective working relationship between Addis and Khartoum. It is also a consequence of the consolidation of the power by Sudanese President Omar al Bashir over the late Islamist idealogue Hassan Al Turabi, whose actions had helped produce the regional war of the 1990s.

This nexus of reciprocal support has been expanded and reinforced partly by the strengthening of multilateral organizations (including the African Union and, to a lesser extent, the Intergovernmental Authority on Development in the Horn-IGAD). Yet an additional change relates to a tacit acceptance between regional powers and their clients and rivals in neighboring countries, who have increasingly understood that their own survival is usually best served by strengthening ties and limiting cross-border sabotage and subversion. Rapprochement between Sudan and Chad in 2010 followed a five year-long proxy war (including dramatic attacks on the respective capitals of Khartoum and N’Djamena) and the sponsorship of militias and rebels across the border with Darfur (see de Waal, 2017: 192). Meanwhile, the improvement in relations between Uganda and Sudan in recent years — and especially Sudan and South Sudan since mid-2013 (see Young, 2015; Deng et al., 2020) — has consolidated this pattern to the west of the Horn (discussed further below).

To the east, Ethiopian interventions in Somalia have likewise shifted in focus. In the mid-1990s, Ethiopian federal forces began to intervene in Somalia to remove threats to Ethiopia’s own restive Somali region posed by Islamist groups on the border. After the Ethiopian-Eritrean war stunted the power of Eritrea (who lost the war decisively, after an impressive start), Ethiopia engaged in a proxy-war against Eritrean-sponsored Islamists in Somalia from the mid-2000s. The removal of the Islamic Courts Union from Mogadishu in late 2006 by the Ethiopian army laid the foundation for the current war involving external forces and Al Shabaab (see Haji Ingiriis, 2018). However, Ethiopia is now a critical node of support for the Somali government of President Mohamed Abdullahi ‘Farmajo,’‘Farmajo,’ which is attempting to unpick federal arrangements in Somalia amid spreading insurgency from Al Shabaab (Felbab-Brown, 2020a).

In the north of the Horn, the 2018 peace agreement between Ethiopia and Eritrea has resulted in much closer relations between Addis and Asmara, and has also led to closer links between Asmara and Mogadishu. However, border disputes between Eritrea and Djibouti persist, and the unresolved tensions between Somalia, Puntland, and Somaliland linger. These intra-Somali divisions have been further exacerbated by Gulf involvement in Somalia (International Crisis Group, 2018).

These alliances have enabled most regimes in the Horn to increase their sense of security, or in some cases (namely Somalia and South Sudan) to outsource aspects of their security planning or operations to more powerful neighbors to offset problems relating to limited resources or dysfunctional security organs. An effect of this is to create a set of relatively durable but generally autocratic regimes in the Horn, which have typically governed on behalf of a narrow range of constituents and interests. There are important differences in the types of authoritarianism associated with different regimes. Some are charismatic and extraverted, as with the Abiy Ahmed administration and the maverick leadership of Lt. Gen Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo (a.k.a. ‘Hemedti’) in Sudan. Others are controlled by brooding figures whose ability to remain in power is rooted in their capacity to manipulate their own state security organs, as in South Sudan under President Salva Kiir and Eritrea under President Isaias Afwerki.

In theory, regional stability and cooperation in the Horn should have been a welcome corrective to damaging regional wars. In practice, the consequences have been disconcerting. It has produced a troubling dilemma: regional alignment maintains regional stability (and thus reduced levels of violence), but at the expense of marginalized areas for whom rule by unrepresentative and/or militarized governments is untenable. Conversely, disarray among the capitals of the region expands and deepens conflict in the region, but offers routes (often violent) for subjugated regions to assert their rights or secede. There are several countries in the Horn where meaningful opposition to a regime has for many years existed only outside of the country’s borders, which remains the case in Eritrea. In the absence of a significant change in the political culture within the most repressive countries in the region, the warming of relations between the regimes of the Horn has had the effect of diminishing the prospects of a meaningful opposition to exert influence.

Despite these changes, states in the Horn nevertheless retain the capacity to engage in destabilization strategies. However, these have tended to be applied to more limited objectives designed to strengthen regime survival in the country undertaking destabilization measures, rather than to fatally weaken neighboring states. An example of this can be seen in occasional acts of cross-border clashes have occurred at this time. Cross-border assistance from Sudan to rebel forces in South Sudan during the early stages of the South Sudanese civil war, where reports of periodic support being availed to the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement – In Opposition (SPLM-IO, the largest armed opposition group in South Sudan) rebels surfaced in 2014 and 2015. Though the extent of this assistance is contested (see International Crisis Group, 2015; c.f. Young, 2017), it was arguably intended to ward off Ugandan involvement in South Sudan’s conflict while encouraging Juba to sever ties with Sudanese rebel groups whom they had relied on for support. In August 2017, assistance from Khartoum was once again detected in limited support for a cross-border attack by SPLM-IO rebels into northern South Sudan. However, this incident was likely unrelated to South Sudan’s conflict, and was instead directed at the US for delaying the lifting of sanctions (see CrisisWatch, 2017).

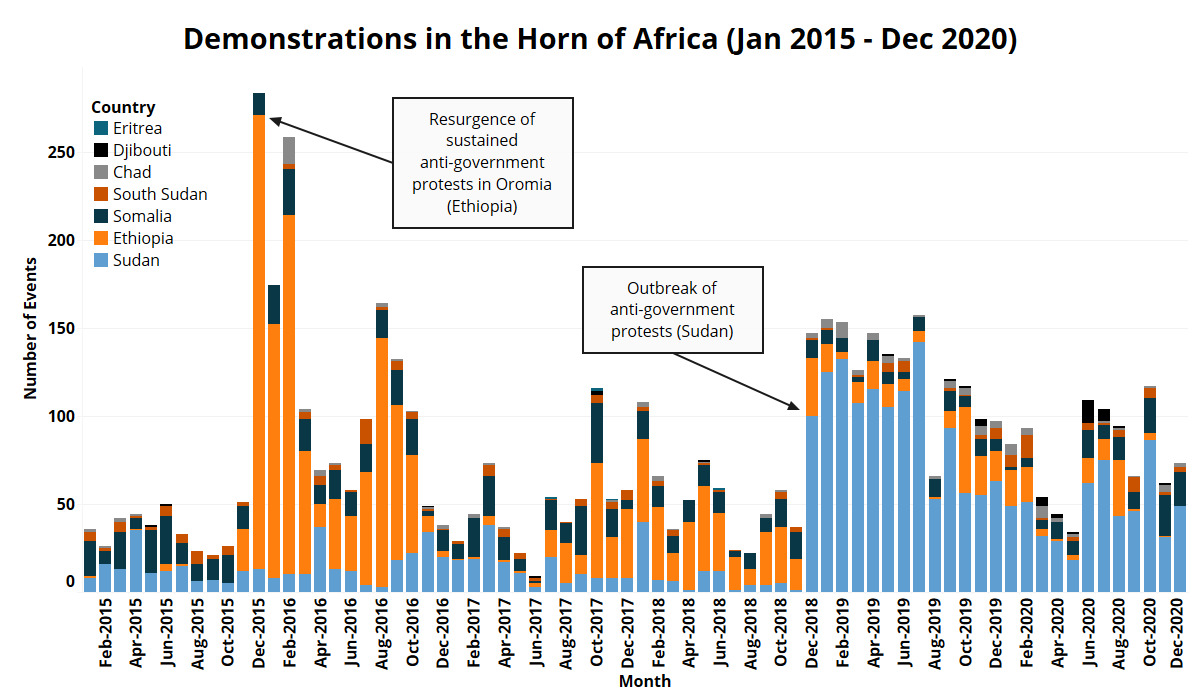

This regional stability risks being challenged, in large part due to internal regime changes in Ethiopia and Sudan. Regime change in Sudan and Ethiopia has been driven by a combination of soaring discontent in the form of protests and riots (see figure below), which has eventually sparked intervention from (typically rivalrous) elites to remove the ailing regime from power.

The Dynamics of Current Cross-Border Violence in the Horn of Africa

If the Horn has become more stable in recent decades, why have concerns over a return to regional conflict been increasing? Much of this has to do with events in late 2020, which has seen an escalating political crisis in Ethiopia spill over into a war in Tigray, amid credible accounts of coordination between Eritrean and Ethiopian forces (Reuters, 11 December 2020; Reuters, 7 January 2021; see also Hagos, 2020). The intensification of an existing border war between Sudan and Ethiopia has compounded fears that a larger war connecting different regional theaters of conflict will transpire.

One way of assessing the likelihood of such a regional conflagration coming to pass is to consider the relations and interests between the principal players of the Horn, and to examine existing patterns of cross-border violence. If regional instability begins to spread, it will likely do so through contentious border areas. Violence has tended to cluster in border areas in the Horn for several reasons. First, disputed borders have often been flashpoints for wars in the Horn, and parties vested in the outcome of border disputes have sometimes been effective at presenting their struggles as being synonymous with national pride, security, and (in the case of Eritrea) survival. Second, they can provide a sanctuary for dissident and rebel groups, especially as many borders cut through ethnic groups who may be politically marginalized on both sides of the border and resistant to an encroachment of state authority. Lastly, control of borders allows for revenue generation by whichever force occupies it, by extension depriving revenue from whomever is not in control of the border. This has important effects on the dynamics of rebel groups in particular, allowing border elites to manipulate revenues to favored commanders and to isolate rivals.

Sudan-Ethiopia

Since the war began in Tigray, concerns have been raised about the effects of the war for Sudan. Much of the fighting in the first week of the war was concentrated in the border regions between Kassala state in Sudan and Western Tigray zone in Ethiopia, as refugees (predominantly Tigrayan, though with some Amhara) fled the region to the Sudanese state of El Gedaref.

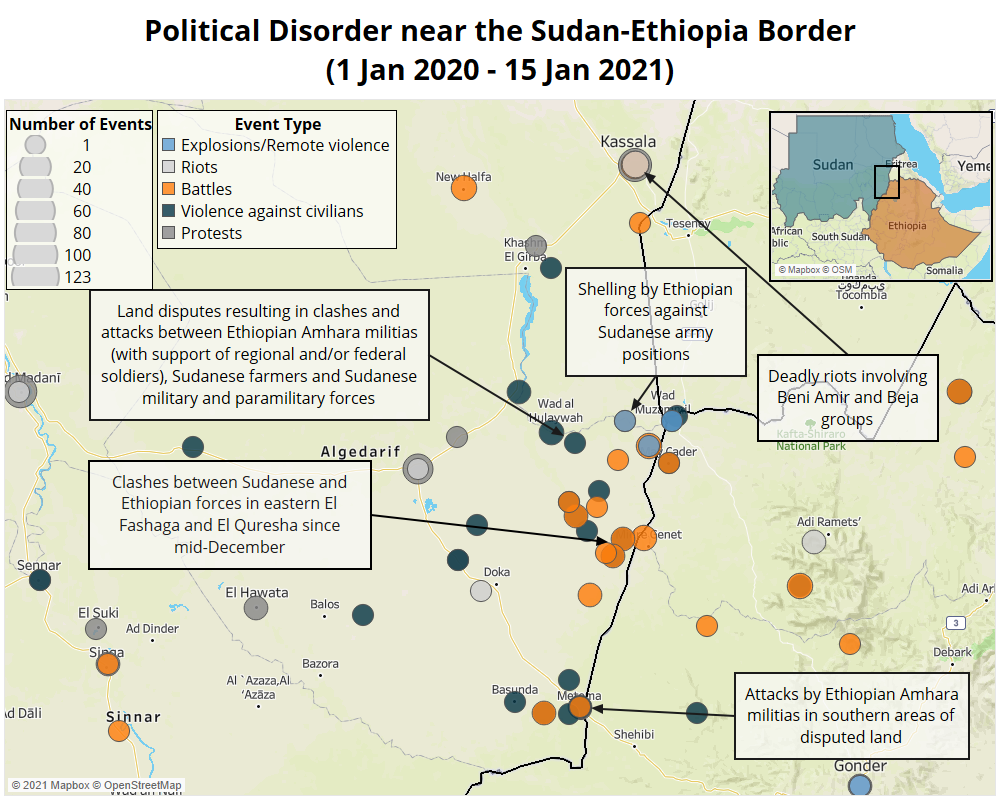

Furthermore, border clashes broke out in mid-December 2020 following the seizure of disputed lands in eastern El Gedaref (often referred to as the El Fashaga triangle) by the Sudanese army several weeks before. Indeed, there has been a bidding war among pundits on the Horn, in which different theories about a regional war involving Sudan and Ethiopia have been proffered.

When the war in Tigray began, Lt. Gen Abdel Fattah Al Burhan (the head of Sudan’s ruling Sovereign Council) dispatched over 6,000 soldiers to the Ethiopian border and announced its closure (AFP, 20 December 2020). On 15 January 2021, Al Burhan claimed that during his meeting with the Ethiopian Prime Minister on 1 November 2020 (two days before fighting broke out in Tigray) that the two leaders had agreed that the Sudanese military would deploy to the border regions, and close the borders “to prevent border infiltration to and from Sudan by an armed party” (Sudan Tribune, 17 January 2021). This no doubt frustrated efforts by the TPLF to secure reliable access to military resources via the Sudanese border, but it also prevented Ethiopian government forces from using Sudanese territory during the critical early phases of the fighting in western Tigray (see International Crisis Group, 2020c; Manek and Kheir Omer, 2020). However, Sudan has since alleged that Ethiopian forces based in the disputed territory were involved in fighting in Tigray (see Bloomberg, 6 January 2021).

During the opening stages of the war in Tigray, interceptions of smuggled goods (including weapons) had been reported by Sudanese soldiers and paramilitaries in the tri-border area with Ethiopia and Eritrea. This may have been a result of unusually high smuggling activity into both Tigray and Eritrea (where Eritrean forces on the Sudanese border have redeployed to the Tigrayan front; see Al Rakoba, 21 November 2020) resulting in higher numbers of seizures, or a deliberate strategy by one or more parts of the Sudanese security apparatus to prevent weapons entering Tigray. It is not clear how many weapons were seized in total, nor what became of these weapons afterwards.

Since early November, escalating border clashes between Sudanese and Ethiopian forces have upped the ante. These represent an intensification of clashes that took place earlier in 2020, which are themselves derived from a set of disputes dating back to agreements signed in the colonial era.

Since March of last year, Ethiopian Amhara militias – suspected of being supported by soldiers from the Amhara region – have attacked Sudanese farmers and clashed with members of the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) in the disputed parts of eastern El Gedaref state (see map below). The clashes are related to a border dispute linked to a treaty (and an addendum to the treaty) signed in 1902 between the British and Ethiopian governments (see Manek and Kheir Omer, 2020; de Waal, 2021a). The area contains fertile farmland, and has continued to be a source of periodic friction (albeit in different guises) over several decades. These disputes have intensified following changes in the regime in Khartoum or Addis, or a deterioration in relations between the two capitals. Given the recent changes at the highest levels in both countries, and various disagreements between the two new administrations, it is perhaps not such a surprise these clashes have occurred at this time.

The demarcation of the border is based on maps made by the Irish geographer Sir Charles William Gwynn in 1903, while serving as a military intelligence officer in Sudan following the British reconquest of 1898. The 1902 treaty was part of a series of negotiations and treaties reached between Britain, Ethiopia, and Italy (who had a colony in Eritrea, and harbored ambitions on Ethiopia) to delineate the tri-border area between Sudan, Ethiopia, and Eritrea from the end of the 1800s and the early 1900s, with a separate 1907 treaty concerning the border between Sudan and southern parts of Ethiopia stretching down to Kenya. Note that despite recent rumours that Sudan is claiming areas of Benishangul-Gumuz in Ethiopia, there are no Sudanese claims in Benishangul-Gumuz. Ethiopia however claims a small stretch of land around Kurmuk in Blue Nile state, on the Sudanese side of the border (see Wubneh, 2015: 452).

Prior to imperial agreements, the area is described in one source as being a ‘transition zone’ between the two countries, which both Sudanese and Ethiopian civilians and refugees would make use of (Wubneh, 2015: 441, 455-56). Another author notes the area was regarded as a haven for outlaws and rebels, and also that groups residing in the region would pay tribute to Welkait (in present day western Tigray) in the latter half of the 1800s (Puddu, 2017: p.232).

Following Sudan’s independence in 1956, Amhara peasants began to settle in the area amid a sesame and cotton boom in north-west Ethiopia. These settlers provided important revenues to Ethiopian elites in the region. Tensions between Ethiopia and Sudan increased after an uprising ushered in a pro-Arab civilian government in Khartoum in 1964, and culminated in a stand-off between mechanized units of Sudan and Ethiopia in 1967. These events occurred during increasingly prickly relations between Sudan and Ethiopia, which had resulted in both governments sponsoring rebels in restive areas of Southern Sudan and Eritrea (then part of Ethiopia). Cross-border attacks by Sudanese soldiers and armed Amhara settlers continued in the early 1970s, as regional Ethiopian elites encouraged the Amhara farmers to become a standing militia after Addis refused to supply resources to establish regular forces which could protect the area (Puddu, 2017: 234-36, 239). Subsequent attempts to demarcate the boundary in an Exchange of Letters between Khartoum and Addis in 1972 went unimplemented, in part because of mounting disputes and fears of economic loss within networks of Ethiopian notables, and also because of the revolution in Ethiopian in 1974. Before the revolution, Sudan re-established control of much of the area, and engaged in clashes with Ethiopian soldiers in February 1974.

Internationally, these areas are recognized as being in El Gedaref state in Sudan, but Amhara residents of the area – as well as Amhara nationalists and some government officials in Ethiopia – say otherwise. The disputed border comprises areas east of the Atbara river in the localities of El Quresha, Eastern El Gallabat, parts of El Fashaga (comprising areas east of a line drawn between Wad Al Hulayfah and Mujadadi), and a slither of Basundah locality north of Gallabat town. These areas are south of the Tekeze/Setit river, which forms the basis for an internal boundary between eastern parts of El Gedaref and Kassala states in Sudan. The Sudanese government says that the 1902 treaty and the 1972 Exchange of Letters confirm the region belongs to Sudan. The Ethiopian government has drawn attention to ambiguities in the description of where the border lies in the 1902 agreement, as well as subsequent adjustments to the border made by Gwynn after the agreement was reached. Concerns over the lack of input from Ethiopian officials while the border was being surveyed by Gwynn have also been raised, as has reported pressure exerted on Emperor Menelik of Ethiopia by the Europeans to sign what some Ethiopians regard as an unfavorable agreement (see Wubneh, 2015: 450-51).

The dispute flared up in the mid-1990s, before largely settling down again. The International Crisis Group’s Project Director for the Horn of Africa Murithi Mutiga has stated that Ethiopian forces entered the disputed region after the attempted assassination of Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak in Addis in 1995, which has been plausibly attributed to a faction of Sudan’s government at the heyday of state Islasmism (International Crisis Group, 2021; see also Young, 2020). Amhara farmers had enjoyed the tacit permission of President Bashir to access the land, after they re-settled in the area since the mid-1990s. De Waal notes that “negotiations between the two governments reached a compromise in 2008. Ethiopia acknowledged the legal boundary but Sudan permitted the Ethiopians to continue living there undisturbed” (BBC, 3 January 2021).

Since this compromise was reached, violence in eastern El Gedaref has gradually increased. ACLED data show that in late June and early July 2014, clashes involving Sudanese Popular Defence Forces (PDF) paramilitaries and regular SAF soldiers against Amhara militias killed at least 20 Sudanese forces, with no reports on Ethiopian fatalities. These disputes appear to relate to control of farmland and assets. In September and October of 2015, clashes between the PDF and Amhara militias continued, killing eight Ethiopians and one PDF paramilitary. In late October, a reprisal attack by Amhara militias killed 16 Sudanese and wounded 12, and resulted in seven abductions. Attacks and abductions also continued throughout November 2015. Attacks and abductions by Amhara militias (and occasional retaliatory action by militia on the Sudanese side) continued in mid-2016 and in late 2018 and late 2019, albeit at a lower level than in 2014 and 2015. Prior to these incidents, there were no recorded events involving both Sudanese and Ethiopian forces in the area since the late 1990s.

After President Bashir was removed in April 2019, constituencies in El Gedaref state began agitating for the return of the land to Sudan, and now have the backing of the recently appointed governor of the state. In late May and late June 2020, Ethiopian forces clashed with Sudanese soldiers on at least two occasions and shelled a SAF camp. A small number of Sudanese soldiers were killed and wounded in these events, while the number of casualties or deaths on the Ethiopian side cannot be confirmed. It is likely these were Amhara regional security forces rather than federal forces (Manek and Gallopin, 2020a), though information on these forces is limited. Clashes then subsided, though periodic abductions and attacks by Amhara militias have continued at a low level.

Since the war began in Tigray in November, a number of developments have taken place in eastern El Gedaref, although details are contested and obscured by a lack of independent verification. The Sudanese army announced on 2 December that it was now in control of significant portions of the disputed land from Amhara militias, though provided no details on whether attacks or fighting occurred as part of its operations (Radio Dabanga, 3 December 2020). Subsequent information suggests that several Ethiopian National Defence Force (ENDF) soldiers were captured by the SAF and returned to Ethiopian authorities on 12 December (Sudan Tribune, 18 January 2021). The Ethiopian government has since stated that SAF entered the area in early November, killing and displacing numerous Amhara farmers, taking advantage of the war in Tigray (Bloomberg, 6 January 2021). In response to these claims, Khartoum has alleged that Ethiopian government-aligned forces moved through the disputed land to attack targets in west Tigray shortly after the outbreak of hostilities between the TPLF and the federal government.

The loss of much of the disputed land was not well-received by Amhara nationalists, who have since led concerted efforts to retake the land (Africa Confidential, 7 January 2021). On 15 and 16 December, Amhara regional forces and militia were reported to have clashed with SAF soldiers in eastern El Gedaref, killing at least 4 and wounding dozens (Radio Dabanga, 16 December 2020; Radio Dabanga, 18 December 2020; Sudan Tribune, 17 December 2020). The fighting took place in parts of El Quresha locality close to the Ethiopian border and in Abu Teyyour in El Fashaga. Lt. Gen. Al Burhan subsequently spent three days in the disputed area. Rapid Support Forces (RSF) paramilitaries have also deployed, amid reports of further clashes on 19 December. Clashes continued on 21 December in El Fashaga, with fighting continuing across 23 to 25 December in both El Quresha and El Fashaga localities, where it also continued on 4 January. Fighting was reported again on 10 January (with unconfirmed reports suggesting an incursion by the Ethiopian air force took place; see Reuters, 13 January 2021). Sudanese sources also stated that unspecified Ethiopian forces killed seven civilians in El Quresha on 11 January (Sudan Tribune, 11 January 2021; Radio Dabanga, 13 January 2021). Al Burhan has since returned to the area, and visited El Quresha locality (Radio Dabanga, 14 January 2020). Eight captured Sudanese soldiers were returned to Sudan by the ENDF on 17 January (Sudan Tribune, 18 January 2021).

Detailed information on the numbers of soldiers and militiamen killed and wounded in armed clashes is virtually non-existent, meaning that caution must be exercised when attempting to gauge the scale of the conflict. There is also ambiguity over precisely which Ethiopian forces are involved in different stages of the clashes. On the Sudanese side, SAF (including SAF Reservists) and Military Intelligence forces are reported to be involved in the fighting. On the Ethiopian side, while Amhara militias have been involved in at least some clashes, it remains unclear whether the fighting involves the ENDF or is instead limited to Amhara regional security forces. If reports of incursions by the Ethiopian air force as well as the return of captured SAF forces by the ENDF are correct, this would suggest that federal forces are involved in at least some capacity.

Meanwhile, several attacks by Amhara militias against Sudanese civilians have occured, including on 2 and 5 January, killing one person in El Fashaga and one person in Basundah, respectively. A Sudanese farmer was also abducted by militias on 10 January south of Gallabat town, and two Sudanese shepherds were killed by militiamen in the vicinity of Gallabat on 16 January (Radio Dabanga, 13 January 2021; Sudan Tribune, 18 January 2021). An additional report of a raid by Amhara militias into Al Fashaga locality emerged on 20 January, though details are unclear (see Al Intibaha, 20 January 2020).

If reports by the Sudanese military are to be believed, it would appear that much of the disputed territory is now under their control. The army has made several announcements proclaiming that a string of small settlements are now under their control (e.g. Radio Dabanga, 23 December 2020; Radio Dabanga, 28 December 2020). Meanwhile, the Ethiopian government has warned its patience for Sudanese activity in what it describes as “Ethiopia’s hinterland” is waning (AFP, 12 January 2021).

Since late December, there have been reports of troops massing on both sides of the border, with unconfirmed reports suggesting Eritrean forces have been deployed both to Eritrea’s border with Sudan, and potentially to parts of Ethiopia along the disputed border inside Ethiopia (see CrisisWatch, January 2021; Sudan Tribune, 27 December 2020). It must be emphasized however that this conflict is presently separate from the war in Tigray, even if some of the same actors are present. There is no involvement by the TPLF, which is a much diminished force at this point, and claims that Sudan (and Egypt) could provide support to the TPLF are at this stage purely speculative. As discussed below, it is also not clear how exactly Eritrea would stand to benefit from involvement in the fighting in eastern El Gedaref, and it is conceivable that Eritrean forces are instead present in order to prevent smugglers from taking supplies and weaponry from Sudan into Tigray. Notably, there have been no reports (supported by evidence) of Sudanese security forces intercepting military material being smuggled into Tigray since November.

Border disputes in the Horn often have a political salience beyond the economic or strategic value of the disputed land in question, which can render them flashpoints for contending governments and militaries. Clashes around Heglig and Abyei along the Sudan-South Sudan border and the 1998-2000 border war between Ethiopia and Eritrea are the most serious examples in recent decades (particularly the latter), which have been escalated by acrimonious history between their belligerents, strategic miscalculation, and the interests of influential political and military elites from border regions in spurring conflict.

The association between border disputes and mass violence may be one reason that fighting in eastern El Gedaref is being linked by some commentators to an impending regional war. However, even though the clashes have become increasingly serious, there are good reasons to moderate notions that a border dispute between Sudan and Ethiopia would escalate to a level approaching that of the Horn’s most notorious border wars.

Sudan is not in an economic position to sustain a large war, nor are its interests presently served by widening conventional military operations to other parts of the border. While the war has enjoyed substantial support among the military (and support among several rebel groups; see Radio Dabanga, 28 December 2020; Radio Dabanga, 15 January 2021), there does not appear to be a large or influential constituency in Khartoum which is heavily invested in the specifics of the disputed land. Arguably, the conflict is instead being used as a stepping stone by Sudan’s military elites to enhance their national standing. It should be noted however that in addition to residents of eastern El Gedaref, the conflict has received logistical and financial support from the Beni Amir community (discussed below), although the details of this are vague (see Al Rakoba, 19 December 2020).

On the part of Ethiopia, federal forces would be over-stretched by conducting a border war alongside counter-insurgency in Tigray, all while dealing with growing unrest in parts of Oromia, Benishangul-Gumuz, and the Southern Nations. However, the increasing prominence of hardline Amhara politicians and security officials since the installment of Abiy Ahmed as Prime Minister in 2018 (see Manek, 2019) does give reason to be concerned that the issue will not be allowed to rest in the event Sudan is able to hold the territory.

In the event that border clashes were to continue, there is a risk that a gradual return to mutual destabilization may ensue in line with previous rounds of proxy warfare during parts of the Cold War and the 1990s. Were this to happen, there are several exposed flanks in both Sudan and Ethiopia, though it must be noted that neither country has thus far indicated a desire to broaden the fighting from eastern El Gedaref, despite previous (unsubstantiated) accusations made by Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed of Sudanese involvement in Benishangul-Gumuz. Although Ethiopia has active conflicts in western Oromia, Benishangul-Gumuz, and Tigray which Sudan could conceivably become involved in, Sudan is much more unstable than Ethiopia and senior officials on both sides of the border will be well aware of this. Turbulence in eastern Sudan could be easily exploited, while a substantial deterioration in political and military stability in Sudan will have unpredictable consequences on the current configuration of power in Khartoum (discussed in the second analysis piece in this series).

Sudan–Chad

Strangely absent from many discussions of Sudan’s transition and the geopolitics of the Horn, the relationship with Chad represents an important (if secondary) element of the regional chessboard. It also speaks to (as with South Sudan, discussed in the following section) a recognition by weaker countries that instability in Sudan is not in their interests. Sudan has traditionally been regarded as a stronger power in the western parts of the Horn of Africa, due to its extensive intelligence networks and capacity to destabilize neighbors.

Turbulence in relations between Sudan and Chad — as well as a festering set of crises in Darfur partly linked to decades of conflict in Chad — helped to ensure that when war broke out in Darfur in 2003 it would soon escalate into a sub-regional conflagration (see Flint and de Waal, 2008). Protracted insurgencies in both countries morphed into increasingly serious proxy wars from 2005 until the end of the decade, and contributed to assorted crises in the Central African Republic. These events have also enabled figures such as ‘Hemedti’ (the commander of the RSF and Deputy Chair of the Sovereign Council in Sudan) to begin building their power bases in the wreckage of the Chad-Darfur borderlands.

By the time President Bashir was removed from power in 2019, relations between Khartoum and N’Djamena remained positive following their rapprochement in 2010. Maintaining good relations with powerful neighbors is an important strategy for Chadian President Idriss Déby to sustain power, as is the determination to avoid lawless border regions from being used to organize attacks against N’Djamena (Tubiana and Debos, 2017). For Khartoum, Chadian support was deemed necessary to curtail the power of two of Darfur’s main rebel groups, and also to regulate the power of Khartoum’s paramilitary allies in the region (several of whom have ethnic and commercial links across the border in Chad).

Present indications suggest that neither country is seeking to change the status quo, though are keeping a cautious eye on developments. Both Al Burhan and Hemedti were involved in raising paramilitaries from Arab-identifying groups during fighting in the Chad-Darfur borderlands in the early 2000s (Tubiana and Verjee, 2019), while Hemedti has ethnic roots with Chadian branches of the Mahariya Rizeigat Arabs (de Waal, 2019b). Notably, Hemedti is also related to Bichara Issa Djadallah, who was twice the Minister of Defense for Chad and who now serves as the President’s Chief of Staff.2 The two are cousins, though they have not consistently been on the same side of the wars in Chad and Darfur. The recent promotions of Bichara Issa Djadallah are a possible indication of the seriousness with which President Déby views the regime change in Khartoum, and the necessity of finding a reliable intermediary to manage the risks posed by Hemedti. The continued rise of Hemedti is reported to have caused anxieties among some non-Arab groups in areas of Chad which adjoin Darfur.

While the Juba Peace Agreement was mediated by South Sudan (and mostly paid for by the United Arab Emirates), Chad has played an important (if low-key) role in the peace process. As discussed in the first analysis piece of the series, this peace process was intended to bring stability rather than progressive change to Sudan.

This goal is no doubt shared by President Déby, who is keen to avoid a return to an era where rebel groups attacked the capital from the east. This is especially so as Chad is currently grappling with insecurity in its north and especially its west. President Déby maintains links with the Zaghawa-led Justice and Equality Movement and Sudan Liberation Movement (Minni Minawi faction) rebel groups in Darfur,3 While President Déby and the leadership of the Darfurian rebel groups are from the Zaghawa/Beri ethnic group, each belong to different sub-groups (see Tubiana, 2008). The political relations between these sub-groups are fragmented and at times antagonistic (see Tubiana and Debos, 2017: 9-13). and reportedly played an important role in facilitating initial peace talks between these groups and Hemedti (International Crisis Group, 2019a: 9, 12-13). Déby also attended the final signing ceremony of the Juba Peace Agreement in Khartoum, and has positioned Chad as a guarantor of the deal (Al Jazeera, 3 October 2020). More broadly, Chadian officials were reportedly concerned by an influx of small arms from Darfur following the removal of President Bashir, which they claimed was a factor which intensified conflicts on the Chadian side of the border (discussed below) (UN Panel of Experts, 2020a: p.10).

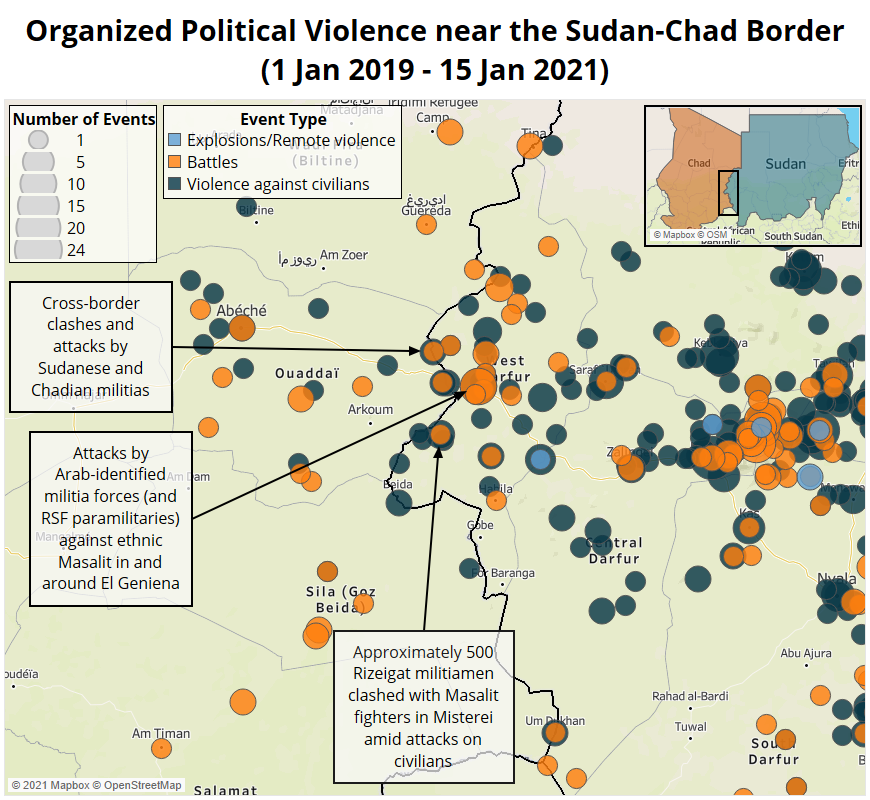

As shown in the map below, there has been significant violence on the Sudanese side of the border since 2020, and particularly in West Darfur state. Although members of the same Arab and non-Arab groups are present in both West Darfur and parts of eastern Chad, the serious violence which engulfed El Geniena and its surroundings in the final days of 2019 and early 2020 does not have any obvious or direct connection to events on the Chadian. Rather, this speaks to the enduring marginalization of the area, and anxieties surrounding national-level changes in Sudan (discussed in the first analysis piece in this series).

Separately, clashes and incursions between Sudanese and Chadian (typically pastoralist) militias have taken place along various parts of the border, albeit infrequently. Information on these clashes is often vague or contested, but suggest clashes are largely revenge attacks in response to cross-border murder or theft. It is unclear whether the Chadian-Sudanese joint border force4 The force was established in 2010 after rapprochement between Presidents Bashir and Déby. Whilst estimates of its size vary, it was believed to comprise around “seven hundred to more than a thousand men” as of 2017 (see Tubiana and Debos, 2017: 21). The current commander is Brig.Gen. Saad Al-Hadi Al-Baloula. remains capable of upholding a degree of relative security in the area. In late 2019, the joint force was weakened following the redeployment of Chadian parts of the force to suppress conflicts in eastern Chad, and from an unspecified number of departures from the Sudanese components of the force (International Crisis Group, 2019a: p.12). The intermittent cross-border violence in 2020 would suggest the force has not yet recovered from these changes.

Although violence has clustered on the Sudan side of the border in 2020, this followed strife in Ouaddaï (reportedly involving Arab militias from Sudan) and Sila provinces eastern Chad in May and August 2019 respectively. These have generally mirrored clashes between pastoralists and more sedentary populations which have continued in Darfur, in which fears and anxieties over ethnic marginalization are often sparked into conflict after the discovery of a dead body from one ethnic group, or disputes over animals grazing on farmland. The contentious politics in the regions of Wadi Fira, Ouaddaï, and Sila had been sharpened by the crisis in Darfur and several years of proxy warfare (and particularly social and political disruption resulting from Janjaweed activity in Chad), though these have tended to exacerbate existing processes and dynamics relating to the regional marginalization of eastern Chad and fears of dominance by Arab groups (International Crisis Group, 2019a: 4-5, 26-27).

Since a state of emergency and a compulsory disarmament exercise were declared in eastern provinces in autumn 2019, ACLED data show violent incidents in Chad’s east declined markedly. This is with the exception of a noticeable uptick in events in December 2020 in which 12 were killed in clashes between farmers and pastoralists east of the regional capital of Abeche on 10 December, and two were killed in ethnic fighting in the department of Koukou Angarana in Sila province on 23 December. These areas are far from the Sudanese border, though heavy fighting was reported on 26 December close to the town of Birak in Wadi Fira province, close to Kulbus locality in the northern part of West Darfur state. This fighting — which involved ethnic Tama and Zaghawa — is reported to have killed 10 and wounded 12.

The currently positive relations between N’Djamena and Khartoum and relatively limited cross-border violence between eastern Chad and Darfur (compared to the 2000s) suggests that so long as political stability is maintained within and between both capitals (as well as in eastern provinces of Chad), then the effects of unrest in Darfur would be largely contained. Indications of growing instability in both countries could however reverse this trajectory, although it must be emphasized that there are currently no signs of a deterioration in relations. As discussed below in relation to Sudan and South Sudan below (and in the second analysis piece in this series), security in western Sudan is to a large extent dependent on whether military and paramilitary elites in Khartoum agree to continue sharing power, or whether rivalries among these elites and their constituencies results in an violent renegotiation of the status quo.

Despites Chad’s reputation in parts of the West as representing a pillar of regional stability in the Sahel, escalating violence in two of its frontiers and signs of discontent in urban areas (particularly among students) would suggest this is not an entirely accurate assessment. Persistent insecurity in border areas with Libya (at least some of which is related to gold mining) and especially in western areas (where Boko Haram fighters have inflicted serious damage against Chad’s armed forces this year; see Africa Confidential, 16 April 2020) may widen discontent among Chad’s ruling factions. Another cause for concern is the collapse of global oil prices during the spring of 2020, which will have a pronounced effect on economic stability in Chad’s mainly oil-dependent economy. This could, in turn, risk a return of the social and labor unrest seen in 2015, which resulted from austerity measures relating to low oil prices and a debt scandal which related to agreements reached with a major international commodities trader (see Tubiana and Debos, 2017: 31-33). It would also put limits on the President Déby’s patronage machine, which undergirds the military and political system in the country.

Sudan–South Sudan

The country most affected by instability in Sudan is South Sudan. Since their separation in 2011, Sudan has increasingly refrained from stoking conflict through arming rogue elements in South Sudan. Juba has gradually reciprocated through limiting support to rebel groups in Darfur and disputed areas along the Sudan-South Sudan border. Yet the upheaval in Sudan caused by the removal of President Bashir in April 2019 has resulted in alarm in both government and parts of the SPLM-IO in South Sudan, since both regarded President Bashir as a known quantity with the power to ensure the agreement would generally be adhered to. Juba’s close involvement in the recent peace process in Sudan intended to reduce the chances of instability in Sudan spreading after the removal of Bashir, which they see as a catalyst for a new round of war in South Sudan.

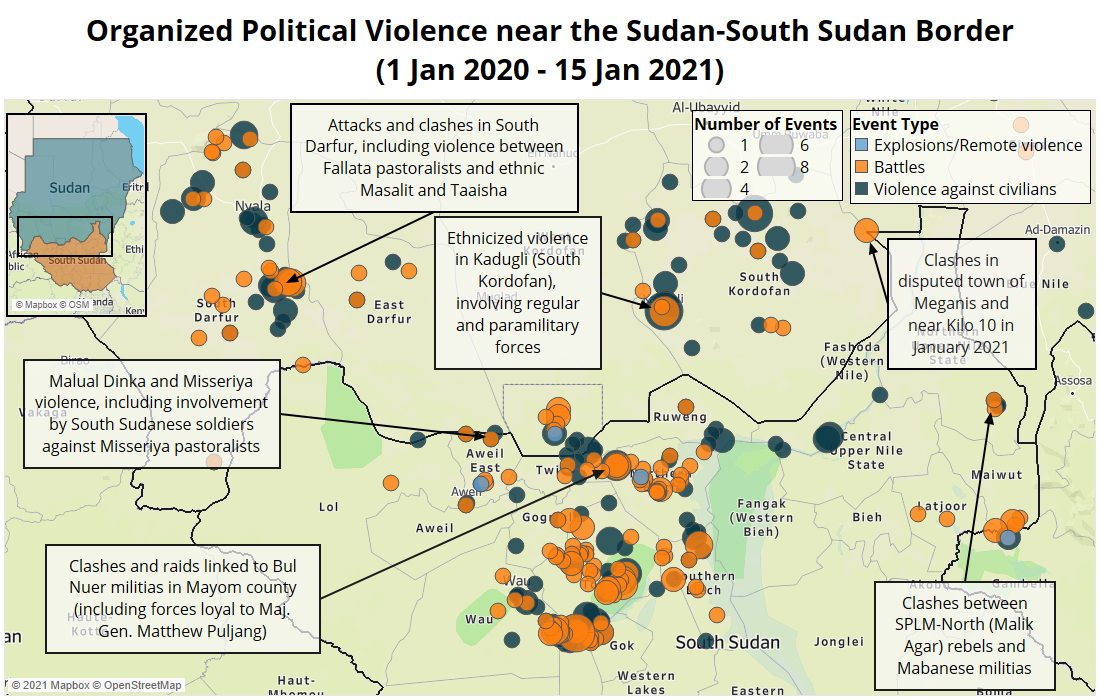

The borderlands between the two Sudans have long been epicenters of fighting and attacks against civilians by Sudanese militias and soldiers. Tensions continued after South Sudan became independent in July 2011, and were aggravated by numerous border disputes (notably of the Abyei and Heglig areas along the center of the boundary) and mutual sponsoring or rebel groups by Khartoum and Juba. The Comprehensive Peace Agreement of 2005 also fudged the issues of the ‘Two Areas’ of Blue Nile and the Nuba Mountains of South Kordofan state (see Young, 2012). Clashes and indiscriminate killings of civilians resumed in parts of these areas shortly before South Sudan’s independence, plunging them into renewed war between the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement – North (SPLM-North, who consisted of branches of the SPLM/A marooned in the north in 2011) and the Sudanese army and paramilitaries.

The steadily improving relations between the two countries since mid-2013 has served to freeze in place (rather than resolve) most of these disputes, though the presence of foreign rebel groups on both sides of the border continued during the first half of South Sudan’s civil war (which began in December 2013, and technically finished in September 2018) as intense counter-insurgency campaigns pursued by both governments ensured these regions remained some of the most violent parts of the two Sudans.

Violence has increasingly become internal to the countries rather than cross-border in nature, although overlaps occurred until rebel groups on both sides of the border were largely defeated by 2016. In recent years, there has been an improvement of ties between border communities on the North-South border, with the notable exception of Abyei (discussed in the first analysis piece in this series). Instability relating to wars in both Sudan and South Sudan has continued at certain points along the shared border, however. In August 2019, the Sudanese government expelled members of Paul Malong’s rebel group based in the edges of South Darfur state.5 Paul Malong is the former head of South Sudan’s army, who was dramatically fired by President Salva Kiir in May 2017. For an excellent overview, see Boswell, 2019. South Darfur is a haven for rebel groups due to the historically weak state presence in southern parts of the state, and the political costs of organizing military intervention in contested border areas. The Kafi Kingi enclave along the South Darfur/Western Bahr el Ghazal is a large contested area between Sudan and South Sudan, as is the border area between South Darfur and Northern Bahr el Ghazal state (see Thomas, 2010; Johnson, 2010). Malong’s rebel group was based in these areas, though were rumored to have been small and ill-equipped, with most soldiers malnourished. He is currently in negotiations with Juba for his return to South Sudan. This led to a series of clashes with the South Sudan People’s Defence Forces (SSPDF, the national army of South Sudan), where most of Malong’s troops were killed or captured (see Rift Valley Institute, 2019).

Meanwhile, in parts of Maban county in Upper Nile state in South Sudan, SPLM-North forces loyal to deposed leader Malik Agar have recently been active (these forces were dislodged from their bases in Blue Nile state in Sudan following the split in 2017, and are entirely based in South Sudan). This has led to clashes between remnants of the group and Mabanese militias (possibly linked to recruitment activities by the SPLM-N Agar faction in refugee camps in the county) in early August or late July 2019, though information on the clashes is limited.

Maban county has previously the site of clashes between Mabanese militias and the SPLM-North (who had occupied areas on both sides of the border for several years) as well deadly attacks against refugees from Blue Nile on several occasions in the past decade, especially in late 2017 (Ammar Hassan, 2020: 30-34). Mabanese militias do not have any current backers within South Sudan, and were instead supported by Khartoum as a means to disrupt SPLM-North activity. The regime change in Khartoum and the inclusion of the SPLM-North Agar faction in the Juba peace agreement means the potential for a return to regular clashes is reduced, though if the SPLM-North Agar (which lost most of its forces to the dominant Abdelaziz el-Hilu faction of the SPLM-North in 2017) continue to recruit forces to be integrated into the Sudaense army then tensions would persist.

Increased activity by SPLM-IO forces in Maban has also been reported in recent weeks, with reports of attacks against Mabanese civilians and (contested) accounts of clashes with the SSPDF. Details of the event are disputed, though have appeared to involve the displacement of thousands of civilians (VOA, 8 January 2021; Radio Tamazuj, 15 December 2020; Radio Tamazuj, 13 January 2021).

Violence has also persisted between Malual Dinka and Sudanese Misseriya pastoralists this year after decades of generally poor relations (see map below). More promisingly, a concerted effort at peacemaking (and compensation payments) took place during 2020. These efforts have been spearheaded by Hussein Abdel Bagi (one of South Sudan’s five Vice-Presidents) and his ally Tong Aken Ngor (the Governor of South Sudan’s Northern Bahr el Ghazal state) as well as Hemedti. This followed a series of revenge attacks which increased over the first six months of 2020, including the killing of 12 Misseriya civilians (with five children among the dead) by SSPDF in late April of early May.

In recent weeks, there have been reports of clashes in the north-east of the border. On 3 and 4 January 2021, fighting between South Sudanese militias and members of the Sudanese El Seleem Belel tribe broke out in the disputed town of El Mogeines/Meganis (Radio Dabanga, 7 January 2021).The town is situated in the far north-west of South Sudan’s Upper Nile state (in areas principally inhabited by ethnic Shilluk/Chollo), though crosses through White Nile and South Kordofan states on the Sudanese side. At least 15 people were killed in the clashes, with two others reported to have been killed on 6 January in the Kilo 10 area to the east. There is still little concrete information regarding the cause of the violence, which is supposedly linked to a dispute over access to a well that escalated to draw in militias on both sides of the border.

There are other concerning situations on both sides of the border. In South Sudan, serious violence involving government soldiers and militias in and around Mayom county has created instability in the critical Unity state. Mayom is the home area of the Bul Nuer clan, from which a disproportionate number of military and security elites belong. Retaining the loyalty of the Bul Nuer has been vital to Juba’s strategy for managing dissent in Nuer-inhabited oil-producing areas, and to defeating the SPLM-IO in Unity state. The strategy has now emboldened elites who present a threat to President Salva Kiir’s authority, leading to a surge in violence in and around Mayom after the president dismissed the powerful Bul Nuer commander Maj. Gen. Matthew Puljang (see map above). Puljang was removed in an effort to quash an emerging Bul Nuer power base from crystalizing (see Radio Tamazuj, 27 April 2020), though this has had the effect of fragmenting forces under his control, likely contributing to insecurity in Mayom.

On the Sudanese side of the border, deadly clashes in the Kadugli area of South Kordofan state have pitted SAF and RSF personnel against each other at several points during 2020. Much like Mayom county south of the border, Kadugli has become a tinderbox in which ethnic fighting involving Nuba and Arab-identiying Baggara groups has spilled over into the security forces.

Both have become dangerous areas to their respective capitals, although the fallout appears to have been contained for now. Importantly, the fighting has been kept on separate sides of the border by the two governments. Were these conflict zones to be brought into contact with one another, then the risk of major factions (SAF and the RSF in Sudan, and the SSPDF and elements of the SPLM-IO) arming rebel groups and militias to spread disorder or to assist in fighting across the border would significantly increase.

While much attention has been directed to the risks to regional security which accompany military clashes between Sudan and Ethiopia, an arguably greater risk in the Horn would result from increasing volatility and instability in Sudan affecting its southern neighbor. Sudan and South Sudan became increasingly close in 2013, despite a series of high-profile disputes in 2012. Indeed, important parts of the military and intelligence apparatuses in both countries as well as the oil economy have become progressively inter-operable in recent years. As David Deng (2019: 3-4) explains:

Historically, political elites in the two countries have tended to view their interactions as zero-sum: a benefit for one side was necessarily interpreted to mean a loss for the other. This is the logic that contributed to the failure of the ‘one country, two systems’ model that would see the two regions progress along distinct but mutually reinforcing development paths, and the rise of the two countries, one system’ model in which similarly repressive, authoritarian states entrenched themselves in both countries and waged wars against their opponents with devastating consequences for civilians.

A consequence of this alignment is that events in the more powerful of the two countries (Sudan) reverberate into the weaker (South Sudan). In the event that Sudan is dragged under by power struggles in Khartoum, then South Sudan fears it will go down with it. This could happen if disorder prevents the South from exporting oil through pipelines which run to Port Sudan, but the greater risks relate to a reignition of South Sudan’s civil war.

If disputes within the factionalized military and security system in Sudan were to take that country into civil war, then the risk is that South Sudan’s government and rebel groups (including rebel groups who have signed peace treaties with the government) would take different sides of a war in Sudan. There are several factions within the SPLM-IO in parts of Upper Nile and Jonglei states which would welcome such an outcome, and who would align themselves with warring parties in Sudan in order to secure arms and war material to increase their power in South Sudan.

Ethiopia-South Sudan

While unrest in Sudan is of the greatest concern to Juba, South Sudan is in an unfortunate position where it risks becoming ensnared in the dispute between Sudan and Ethiopia if its two more powerful neighbors are unable to find a compromise. Several regional experts have drawn attention to the increasing closeness of Egypt and Sudan (e.g. Manek and Gallopin, 2020b; de Waal, 2021b), who have long-standing military, cultural and commercial links. These accounts have raised the prospect of an emerging alignment between Cairo, Khartoum, and Juba, at least on the matter of the GERD and Nile hydro-politics. There are also indications of growing (though still modest) commercial and infrastructure investment in South Sudan on the part of Egypt (see, e.g., Africa Oil & Power, 7 January 2021).

It does not necessarily follow from this that South Sudan will take a side in a hypothetical Ethiopia-Sudan war, though its close links to Sudan make it exposed to the potential fallout. Regional stability is of significant concern to Juba, whose regime survival strategy depends on a high degree of continuity in its relations with critical political, military, and economic partners. Ethiopia’s regional influence — as well as its status as a security arbiter along the shared borders with South Sudan — means Juba will be watching events closely.

The repercussions of disorder in Ethiopia and the border war in El Gedaref have thus far been limited for South Sudan, and Juba will be eager to ensure it remains that way. At present, the war in Tigray does not immediately affect South Sudan. Contrary to commentary at the start of the crisis in Tigray — which predicted an exodus of Ethiopian peacekeepers from the UN forces in South Sudan and the disputed Abyei area — there has been no significant withdrawal. Moreover, fears of a decline in Ethiopia’s ability to uphold peace agreements in South Sudan (also predicted towards the start of the crisis) are misplaced. Abiy has been a poor mediator in South Sudan (and in Sudan), and lacks the patience and personal connections with the South Sudanese elite required to exert effective influence in peace talks in South Sudan. Ethiopia’s role in supporting the current peace process (signed in 2018) is now less important than during the previous peace process (reached in 2015, and which collapsed in 2016).

Despite the substantial distance between South Sudan and the disputed border areas between Ethiopia and Sudan, the implications of an escalation in clashes in the El Fashaga triangle will be of concern to South Sudan’s elites. Juba’s interests are to maintain stability in Sudan, and to find sources of cash to sustain the most important parts of the country’s vast politico-military system. Juba also aspires to salvage its once-positive international reputation, and hosting and mediating the Juba Peace Agreement is regarded as an important means to do so (International Crisis Group, 2019b: 11).

President Salva Kiir has called for Sudan and Ethiopia to de-escalate the border conflict in eastern El Gedaref (Sudan Tribune, 8 January 2021), and has offered South Sudanese assistance in mediating (Radio Dabanga, 14 January 2021). This is presumably because he is aware that South Sudan would suffer disproportionately if the conflict were to threaten stability in Sudan, or drag South Sudan into a proxy war with Ethiopia. The border regions between South Sudan and Ethiopia are host to a number of ethnic groups who have been particularly resistant to the imposition of central authority by various incarnations of the state in South Sudan, and have also been a hotbed of rebel activity. These include several eastern Nuer clans and parts of the Murle ethnic group, with elements of both groups being linked to rebellions in South Sudan in the past decade. More recently, South Sudan’s troubled Jonglei state has in the past year experienced complex violence aggravated by clandestine military support by various security factions (see UN Panel of Experts, 2020b), which has created conditions for famine in Pibor county.

Meanwhile the Nuer have fraught relations with the Anyuak ethnic group, which has been a source of regular tension and violence in the Gambela region of Ethiopia (see Feyissa, 2009). Finally, residents of Maban county (which sits on the tri-border area between Sudan, South Sudan, and Ethiopia) have a difficult relationship with the major factions vying for power in South Sudan, and have previously been willing to act as proxies for Sudan (Ammar Hassan, 2020).

Were relations between Juba and Addis to deteriorate, this would be to Juba’s disadvantage. The vulnerable areas of the border fall largely on the South Sudanese side. South Sudan’s complex military system is not a reliable guarantor of security in South Sudan, and a resource intensive deployment to either Sudan or Ethiopia would risk inflaming relations with border communities. The presence of both hardline SPLM-IO elements and Nuer militias along much of its north-eastern borders poses an additional complication, and could be exploited by Addis.

Ethiopia-Somalia6 The author expresses his gratitude to Mohamednoor Daudi Ismail for providing useful information and insights for this case study.

Somalia remains the most consistently unstable part of the Horn, with a greater number of battles and remote violence events than any other country (see figure below). Complex conflict dynamics involving Islamist groups, clan militias, a weak federal government (often at odds with federal regions) and international forces have spread in recent years, with ENDF soldiers closely involved in counter-insurgency activities and regime support for Mogaidshu. Since its dramatic intervention in 2006, Ethiopian forces have taken an active role both within the auspices of the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM), and has around 15,000 soldiers in Somalia outside of AMISOM (For detailed information on recent developments within Somalia, see ACLED 2020a and ACLED 2020b).

Since 2017, ENDF troops have played an important role in upholding the rule of President ‘Farmajo,’ who has sought to re-centralize power amid spreading tensions with regional states in the south of the country (see International Crisis Group, 2020b). They have also helped to secure the election of the regional government of South West State amid persistent Al Shabaab activity in the area, while facilitating the arrest of Al Shabaab defector Mukhtar Robow after he threatened to prevail in elections against Farmajo’s preferred candidate (Felbab-Brown, 2020a). While President Farmajo is reported to back the dismantling of the TPLF (which would weaken certain political opponents; see Kirechu, 15 January 2020), the ripple effect of the war in Tigray carries risks to Mogadishu.

The withdrawal of non-AMISOM Ethiopian forces will impede efforts to wrest Bu’aale town in Middle Juba from Al Shabaab, while providing new openings for Al Shabaab to increase their presence in areas now vacated by Ethiopian soldiers. There have also been reports of clashes along ethnic lines between Ethiopian AMISOM forces (see Garowe Online, 6 December 2020). The withdrawal also weakens President Farmajo, who was counting on support from Ethiopian soldiers in the elections which are taking place between now and February. The subsequent announcement by the former US president Donald Trump that US Special Forces in Somalia would withdraw in January 2021 will further compound these pressures (Felbab-Brown, 2020b), as could the escalating diplomatic spat with Kenya (Deutsche Welle, 15 December 2020).

Eritrea-Ethiopia-Sudan

After the onset of war in Tigray, evidence has gradually accumulated showing considerable involvement of Eritrean soldiers in much of Tigray (see, e.g., The Daily Telegraph, 8 January 2021). The TPLF have also fired missiles at the airport and the powerful Ministry of Information headquarters in Asmara (see map below), while numerous accusations implicating Eritrean forces in attacks, systematic looting, and abductions of Eritrean refugees in Tigray have been made (e.g. UNHCR, 14 January 2020; de Waal, 2020b). Furthermore, drones have reportedly been launched from the UAE-run military installation at Assab into Tigray (Africa Confidential, 19 November 2020; de Waal, 2020c)

The return of Eritrea to the regional stage following decades of isolation has invited much intrigue and speculation, with some accounts highlighting Eritrea’s pivotal role in a potential regional conflict (e.g. Manek and Kheir Omer, 2020). In order to understand some of the implications of Eritrea’s apparent resurgence, it is worth outlining the capacities of Eritrea’s security forces.

At an estimated 200,000 soldiers, Eritrea’s army is extremely large, though its size obscures the fact that it has essentially been used as a machine of both social control and to forcibly recruit labor for business endeavors linked to senior military commanders. Desertions of those facing indefinite military conscription are reportedly common (Kibreab, 2017: Chs.3 and 4). This raises doubts about its effectiveness, loyalty and overall force-readiness of the Eritrean Defence Forces (EDF) at the mass level. Reports of forced conscription in Eritrea both before and after fighting broke out in Tigray would not offset these problems, but instead would perpetuate them. There are unconfirmed reports which suggest members of the Beni Amir clan are refusing to participate in the action, which will be of a concern to Eritrean authorities if reports of Beni Amir rebels and dissidents gathering in the troubled Kassala state of Sudan are correct (see Manek and Kheir Omer, 2020).

In addition, a lengthy arms embargo in place until 2018 has prevented the military and air force from modernizing and even maintaining its aging Soviet-era equipment (IISS Military Balance, 2020: p.476). The IISS also states the EDF has nineteen infantry divisions and one commando division, though reports of additional divisions (including additional commando divisions) have emerged during the war in Tigray. There are several better resourced and trained Presidential Guard units, of which there were three in 2010 (Plaut, 2019: 199).

Problems with loyalty and capacity permeate the overall structure and leadership of the EDF. The EDF exists in a state of constant fluctuation, with senior commanders often pitted against each other rather than Isaias. The organizational structure of the EDF is malleable and its senior staff continually rotated. This approach was initially employed to curtail influential commanders from the insurgency after Eritrea won its independence in 1993. Following the devastating war with Ethiopia (1998-2000), additional reorganizations transferred greater economic and political power to military zones under loyal commanders. These commanders are rotated frequently to prevent them from forming bonds with their soldiers, and are watched by deputy commanders who are considered pliant to the President (Kibreab, 2017: Ch.3).

Through dismembering and de-professionalizing the EDF, President Afwerki has weakened the capacity of the once renowned military force, and by extension the capacity of the army to unseat the President (Clapham, 2017: 132). Nonetheless, a coup attempt occurred in February 2013 by disaffected elements of the army, who attempted to seize the Ministry of Information (an important institution to control in a context where communications are tightly regulated). The coup failed due to the refusal of other elements of the army to join the mutineers, potentially because the military communications system is under the control of the president’s office (Plaut, 2019: 201).

Eritrea adjoins volatile regions in Sudan, which is one reason fears of a spreading regional war have surfaced. As de Waal (2020c) notes, Eritrea has much to gain from the crisis in Tigray. In addition to a very large transfer of assets and resources from Tigray to Eritrea via systemic looting (which may also provide new revenues to EDF commanders), the war in Tigray alleviates the threat posed to President Afwerki by the TPLF. Yet it is not clear how Eritrea’s (or President Afwerki’s) interests would be directly served by involving itself in the current fighting in eastern El Gedaref, nor by engaging in a prolonged regional war. As illustrated above, the army is not in a position to cope with sustained operations without substantial external assistance, and this could risk distracting from the President’s apparent goal of eliminating the TPLF. Indeed, it is unclear how Eritrea is paying for its deployment in Tigray (even if looting is likely offsetting some of the costs), nor how it would finance operations in other parts of the Horn.

In the event that the (currently separate) theaters in Tigray and the El Fashaga triangle were to merge, Eritrea would have the option to exacerbate existing problems in eastern Sudan. Eritrea has influence over rebel groups in eastern Sudan, including among the Eastern Front coalition (Africa Confidential, 19 November 2020). The Eastern Front was established out of factions of the Beja Congress and the (far weaker) Rashaida Free Lions rebellions, but was dominated by Beja clans. Eritrea had earlier trained ethnic Beja rebels in the mid-1990s following a marked deterioration in relations with Sudan, and supported operations by Beja and SPLM/A units in eastern Sudan in the late 1990s (see International Crisis Group, 2013; de Waal, 2004: pp.201-202). Sensing the need to build more positive relations Khartoum in the aftermath of the devastating Ethiopian-Eritrean war, Asmara organized the rebels into the Eastern Front, which brought together disparate political and rebel factions for the purposes of arranging peace talks with Khartoum in the mid-2000s. In addition to staving off threat off an alliance against Asmara between Khartoum and Addis, this had the effect of limiting the potential for rebellion in its own marginalized Muslim regions in the western lowlands of Eritrea. It should however be noted that there is ambiguity over the current status of the Eastern Front, who were involved in a stalled integration process into SAF for many years. Moreover, there is no evidence which directly links them to recent violence in eastern Sudan.

As discussed in the second analysis in the series, the states of Kasala and Red Sea have been convulsed by riots and clashes, with disputes between the Beja and Beni Amir constituting the central axis of the violence. Eritrea has much more positive relations with the Beja than with its own restive Beni Amir population. The Beni Amir are present on both sides of the Sudan-Eritrea border, and experience discrimination and marginalization in Eritrea in particular (Tronvoll and Mekonnen, 2017: Ch.8). This is a situation Eritrea could more comfortably exploit, so long as the President feels his security interests were served by doing so.

There are many unanswered questions regarding Eritrea’s involvement in the war in Tigray, including the paradox of how an army which has been hollowed out from within has been able to prepare for, finance and enact sustained operations in Tigray. Such questions will hopefully be answered in the fullness of time, and may require a reappraisal of the capacities and durability of Eritrea’s military system as well as its sources of income. However, assuming the information above is broadly accurate, it would seem that the president’s need to appease senior commanders — while contending with ingrained problems relating to outdated equipment and forced conscription — means that the EDF is an instrument which is likely to constrain as well as enable.

Conclusions