The COVID-19 crisis has exacerbated existing inequalities and political faultlines in the US, contributing to a surge of unrest throughout the country. New analysis of ACLED data — now extended to the beginning of 2020 — reveals the full scope of the pandemic’s impact on American protest patterns for the first time. All data are available for direct download. Definitions and methodology decisions are explained in the US Coverage FAQs and the US methodology brief. For more information, please check the full ACLED Resource Library.

Executive Summary

In March 2020, the Trump administration declared the novel coronavirus pandemic a national emergency in the United States. Although the US is home to just 4% of the world’s population, it now accounts for a quarter of all confirmed COVID-19 cases and a fifth of the death toll (New York Times, 2021). A year on, more than half a million people have died of COVID-19 across the country (CDC, 2021), and the new Biden administration has officially extended the national emergency beyond its March 2021 expiration date (CNBC, 25 February 2021).

The health crisis has exacerbated existing inequalities and political faultlines in the US, contributing to a surge of unrest throughout the country. New analysis of ACLED data — now extended to the beginning of 2020 — reveals the full scope of the pandemic’s impact on American protest patterns for the first time.

Key Findings

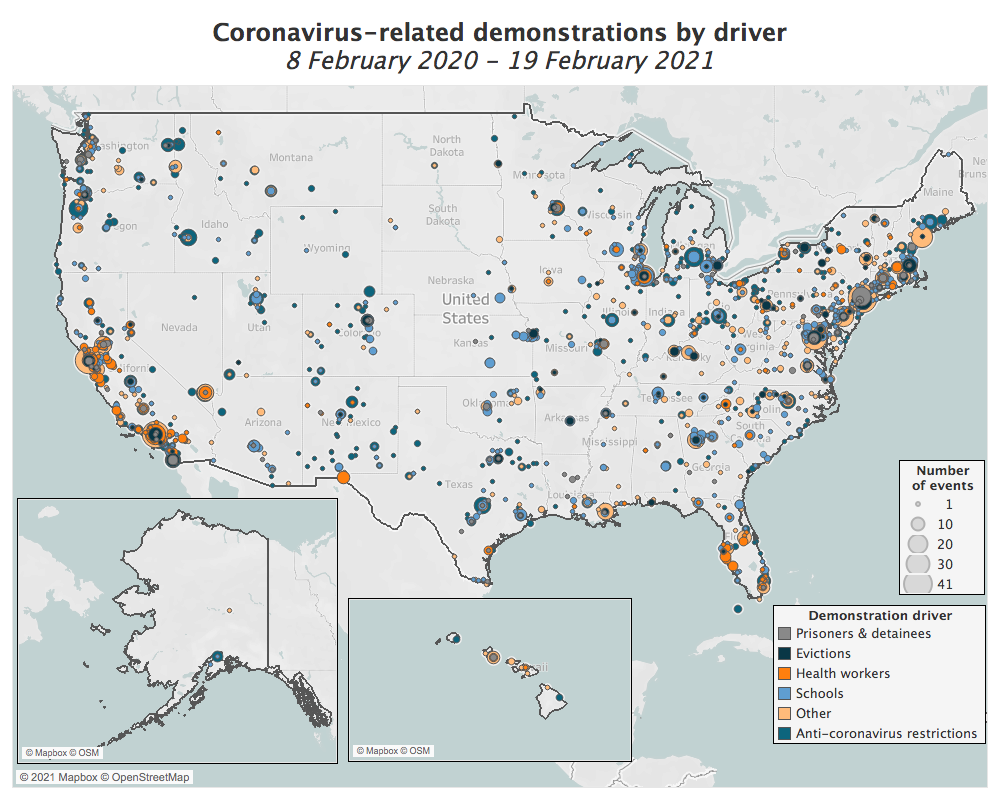

Trends in pandemic-related demonstrations are closely correlated with trends in COVID-19 cases, with spikes in unrest matching infection waves reported throughout 2020. ACLED data show that the majority of these demonstrations have been organized around five main drivers: the risks faced by health workers, the safety of prisoners and ICE detainees, anti-restriction mobilization, the eviction crisis, and school closures.

- Health workers have protested to call for safer working conditions and a stronger government response to the pandemic. Demonstrations organized by health workers have contributed to protest spikes throughout the year, with surges during each wave of the pandemic. These protests have been peaceful and less than 1% have faced intervention from the authorities. Health worker protests have taken place in 38 states and the District of Columbia.

- Prisoners and ICE detainees are at high risk of contracting the coronavirus due to a combination of cramped quarters, poor ventilation, limited time outdoors, and restrictive measures that prevent the use of masks and other PPE. Demonstrations by and in solidarity with prisoners and ICE detainees have called on the government to reduce these risks, and have been organized in 37 states and the District of Columbia. Solidarity demonstrations have been overwhelmingly peaceful — over 99% of all events — and the majority of demonstrations involving prisoners and detainees have been peaceful as well — over 77% of all events. Nevertheless, demonstrations by prisoners are frequently met with force: in more than a third — over 37% — of all peaceful coronavirus-related protests held by prisoners and detainees, guards have used force like firing pepper spray and pepper balls.

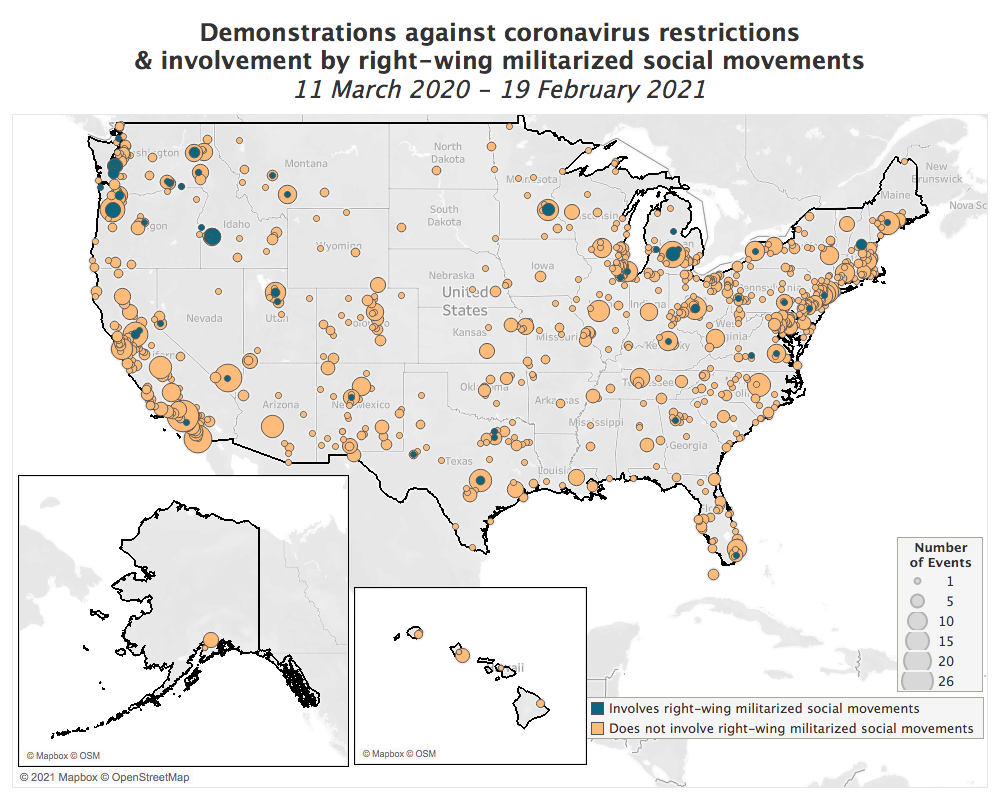

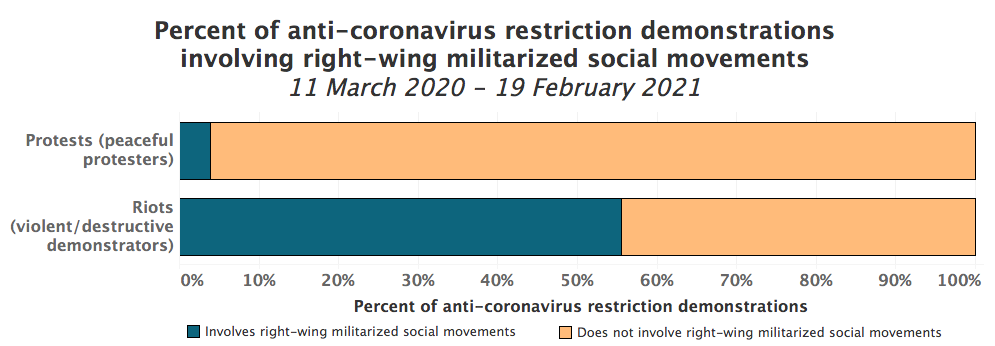

- Government measures to curb the spread of the coronavirus have prompted thousands of anti-restriction demonstrations calling for the country to reopen. These demonstrations have taken place in every state and the District of Columbia. Right-wing mobilization against COVID-19 restrictions has been a critical means for far-right armed groups to build networks around the country, serving as a key precursor to ‘Stop the Steal’ organizing after the election leading up to the US Capitol riot in January 2021. Over 23% of all demonstrations involving right-wing militias and militarized social movements across the country have been organized in opposition to pandemic-related restrictions. Anti-restriction demonstrations involving these groups turn violent or destructive over 55% of the time, relative to less than 4% of the time when they are not present, underscoring the destabilizing role that militias and other militarized movements can play in right-wing mobilization.

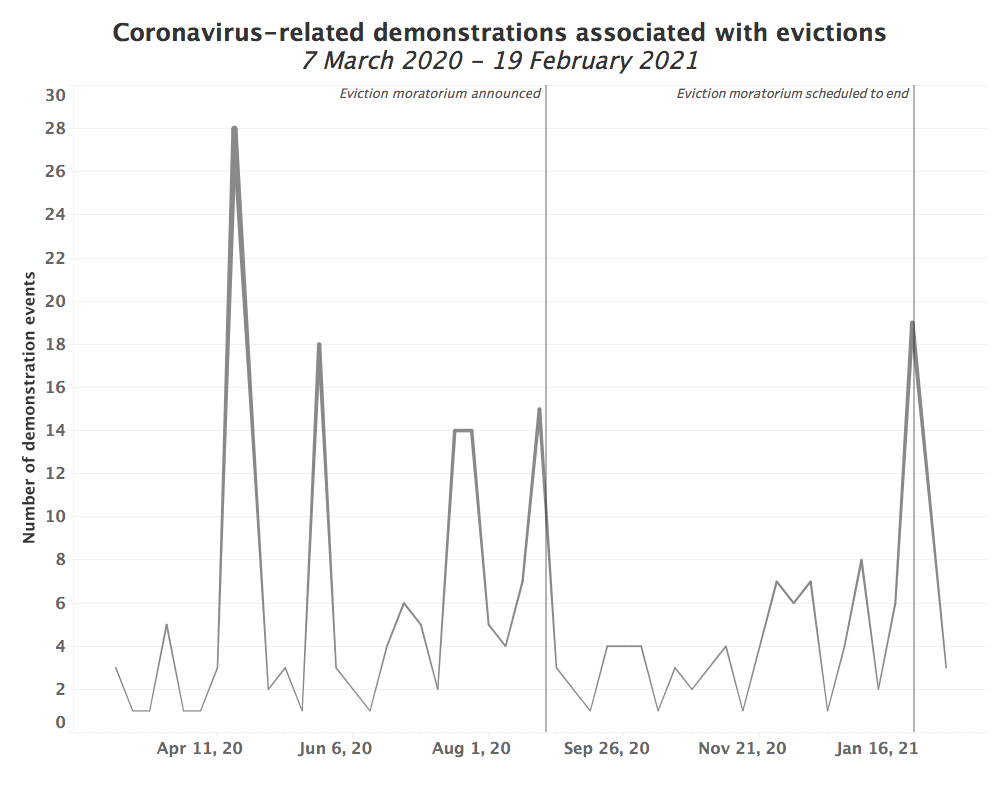

- Demonstrations over the eviction crisis triggered by the pandemic — largely spearheaded by the ‘Cancel the Rents’ movement — have urged the government to cancel rent and provide financial relief amid the economic downturn. These demonstrations — which have been overwhelmingly peaceful, at over 99% of all events — have fluctuated in response to federal and state relief packages as well as measures to postpone or ban evictions. These demonstrations have taken place in 35 states and the District of Columbia.

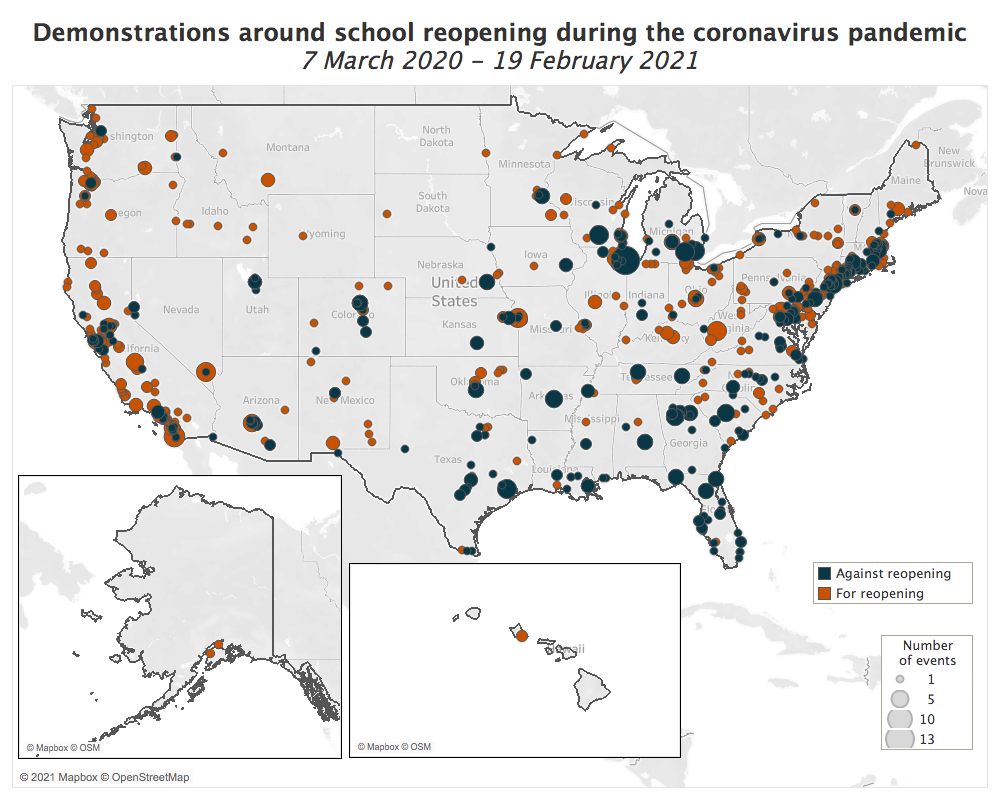

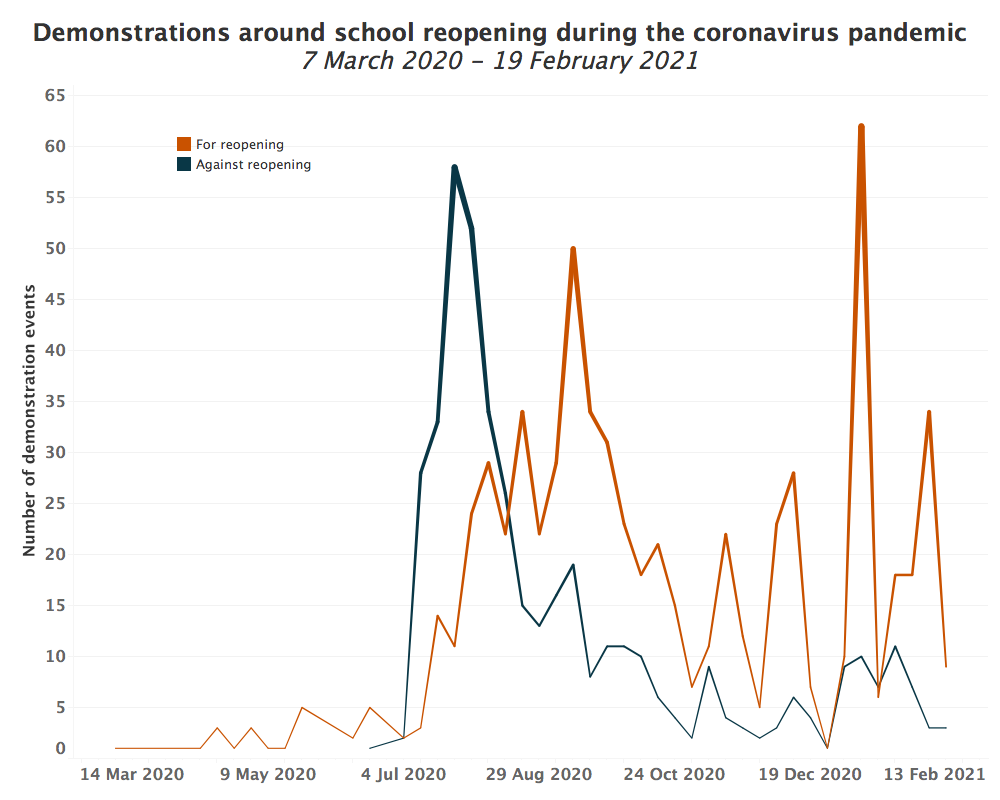

- The battle around school reopenings has led to waves of protests both for and against a return to in-person teaching. School-related demonstrations account for approximately 25% of all coronavirus-related demonstrations in the US. Approximately two-fifths of these demonstrations have been organized against the reopening of schools (i.e. for continued online learning) while about three-fifths have been organized in favor of reopening (i.e. for in-person teaching). Both movements have been widespread geographically, with 43 states and the District of Columbia hosting demonstrations against reopening and all but Arkansas and District of Columbia hosting demonstrations in support of reopening.

The full picture of the Biden administration’s response to the crisis — and its impacts on pandemic-related protest patterns — remains to be seen. If the government is able to meet Biden’s promise that vaccines will be available to all Americans by the end of May 2021 (NPR, 3 March 2021), and if this in turn leads to a sustained decline in COVID-19 cases, pandemic-related mobilization may subside.

At the same time, much of the population remains resistant to vaccination (The Hill, 10 February 2021), which could stymie efforts to combat the virus and reopen the country. If partial vaccination prevents a decrease in new cases, or enables a future resurgence, it could prolong lockdown measures, prompting an increase in anti-restriction protests. Prolonged lockdowns will do additional harm to the economy, which will fuel further unrest over the eviction crisis as well as demonstrations calling for financial support.

However, if the administration responds with a mandatory vaccination policy or imposes new national restrictions to curb the pandemic, it could reinvigorate right-wing mobilization, including militia activity, against the federal government. While right-wing organizing and militia activity has temporarily abated amid the crackdown on groups and individuals connected to the Capitol riot, these networks — bolstered during reopen rallies throughout 2020 — are likely to reactivate when the next politically salient moment arrives. The ‘anti-vax’ movement could serve as such a catalyst, as anti-vaccine activists are already a growing force at reopen demonstrations (New York Times, 4 May 2020), and have increasingly found common cause with right-wing anti-lockdown demonstrators as they shift their focus to the vaccination rollout (New York Times, 6 February 2021). Many of these demonstrators are new to the ‘anti-vax’ movement, joining as a reaction to the coronavirus pandemic and what they perceive as an attack on civil liberties mounted by the government in response to the health crisis (New York Times, 6 February 2021). Building on the reopen organizing that began in early 2020, organized opposition to the vaccine rollout in early 2021 could serve as an important nexus allowing militias, militant street groups, and other right-wing social movements to develop additional networks for future mobilization.

A year into this national emergency, months after an attack on the seat of government, the US is at a crossroads. How the country reacts to these new pandemic and political phases will present a clear signpost for the future of political violence and protest in America.

Introduction

The World Health Organization declared the novel coronavirus a pandemic in early March 2020, and the Trump administration announced a national emergency in the United States soon after. Although the US is home to just 4% of the world’s population, it now accounts for a quarter of all confirmed COVID-19 cases and a fifth of the death toll (New York Times, 2021). A year on, more than half a million people have died of COVID-19 across the country (CDC, 2021), and the new Biden administration has officially extended the national emergency beyond its March 2021 expiration date (CNBC, 25 February 2021).

Not everyone has been impacted equally by the coronavirus outbreak in the US, and the pandemic is already having a range of second-order effects. The virus poses heightened risks for frontline workers, like healthcare professionals, as well as those in confined and overcrowded spaces, like prisoners and detainees. The pandemic and measures to contain the virus have also led to a devastating economic downturn, with both direct effects, like the closure of businesses, and indirect consequences, like mass evictions of those who have lost their jobs. Other repercussions will not be fully felt for years. With schools closed to in-person teaching, the divides between students from different socioeconomic backgrounds have widened. Some have excelled in online learning through support from tutors or ‘pandemic pods’ (CNN, 25 August 2020), while others without reliable internet access or close day-to-day parental support have struggled (USA Today, 4 February 2021). As millions of women exit the workforce to accommodate their children (CBS News, 8 February 2021), efforts to narrow the economy’s gender gap are also under threat. And many of the pandemic’s direct and follow-on effects are disproportionately impacting communities made up of Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) (NPR, 30 May 2020; Poynter, 17 September 2020).

Simultaneously, the pandemic has provided an opportunity for far-right armed groups to build networks in opposition to state restrictions aimed at curbing the virus, such as mask mandates or business closures. Many of these groups claim to oppose ‘big government’ and view COVID-19 restrictions as an ‘overstep,’ allowing them to interface with a wider movement of activists on the right organizing against lockdowns. Such cross-pollination in early 2020 helped groups build new connections and coalitions, which have become increasingly active over the course of the past year.

ACLED data now cover the entirety of 2020,1ACLED coverage of the US initially began as part of the US Crisis Monitor, a joint project with the Bridging Divides Initiative at Princeton University. and weekly real-time coverage continues. As of February 2021, the dataset includes more than 25,000 political violence, demonstration, and strategic development events across the US. These data allow for a full review of trends throughout an unprecedented year and into the start of 2021 for the first time, from unrest over the pandemic and a global movement challenging systemic racism and police brutality, to a contentious election in the fall and a spike in right-wing mobilization against the results that culminated in an attack on the US Capitol Building. These ongoing trends underscore the importance of real-time data collection to monitor key developments and emerging patterns into the new year.

In recent reports, ACLED analyzed the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement over the summer of 2020, the role of right-wing militias in political violence and protest activity leading up to the election, and right-wing ‘Stop the Steal’ mobilization in the aftermath of the vote. With data coverage now extending to the beginning of 2020 and the start of the coronavirus outbreak, this report explores the pandemic’s impacts on protest patterns across the US.

The Pandemic’s Impact on Demonstration Patterns

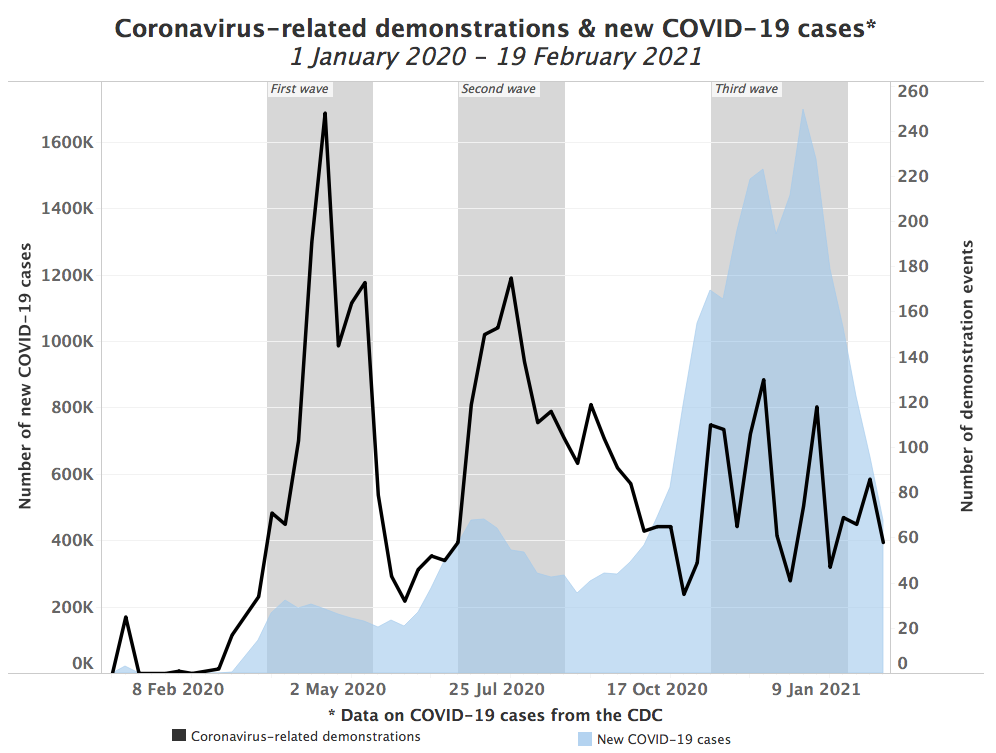

Pandemic-related demonstration patterns (see line on graph below) have largely mimicked trends in the number of new COVID-19 cases,2COVID-19 case data are sourced from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). matching the waves in reported cases throughout 2020 (see filled area on graph below) (for more on the relationship between COVID-19 and demonstration patterns, see this spotlight infographic from ACLED’s COVID-19 Disorder Tracker). Infection waves refer to a phenomenon in pandemics where infections spike as the virus infects a first group of people, appear to decrease thereafter, and then increase again, infecting a different subset of the population, with each of these ‘spikes’ referred to as a wave (MedicineNet, 2020) (gray bands in graph below).

At first, the pandemic and ensuing restrictions on movement reduced overall demonstration activity in the US, similar to trends seen around the world (ACLED monitors these trends globally through the COVID-19 Disorder Tracker). California became the first state to issue a stay-at-home order in March, six days after the declaration of a national emergency (Office of Governor of California, 19 March 2020). As coronavirus cases rose, states imposed a wide range of restrictions, including limiting access to public places (e.g. schools, bars, restaurants), the size of gatherings, and non-essential travel, while mandating social distancing and in some cases mask-wearing. Restrictions vary considerably across and within states in terms of severity and expected duration. At least 75% of US counties and 95% of the national population have been affected by some type of coronavirus-related restriction (Center for Disease Control, 4 September 2020; New York Times, 20 April 2020).

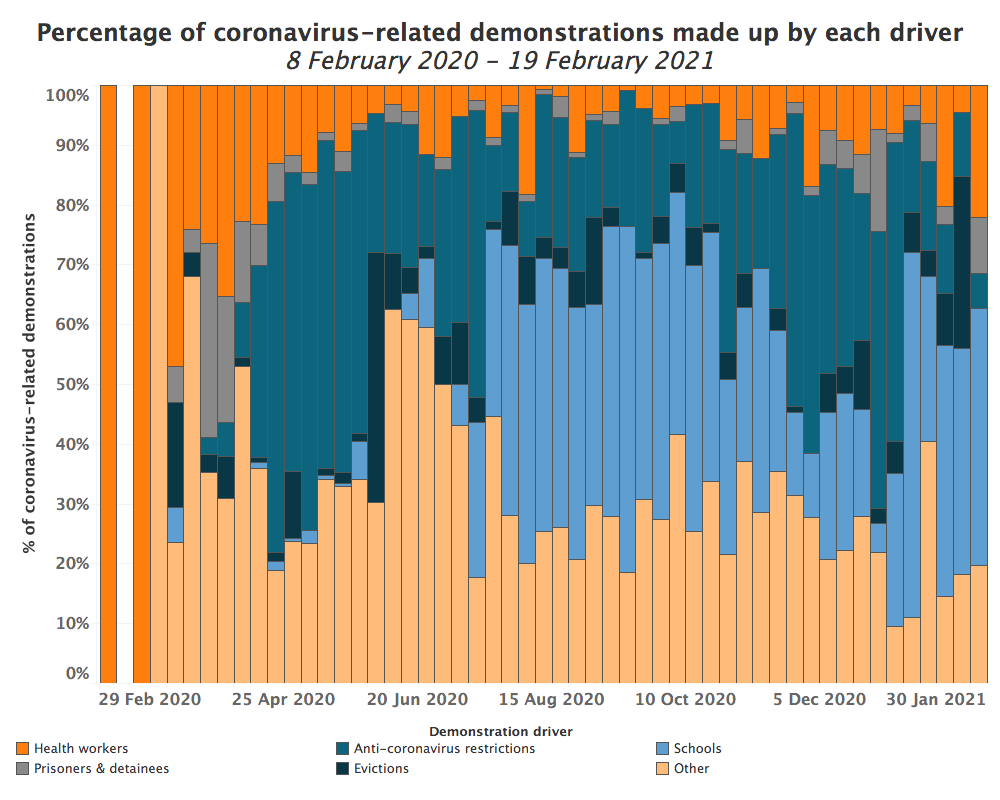

Demonstrations driven by the impacts of the coronavirus pandemic — including these new restrictions — began soon after the initial lockdown, with different drivers fueling trends at different times (see graph below).

In the early days of the crisis, especially prior to the national emergency declaration, health workers were the primary actors driving coronavirus-related demonstrations (in orange in graph above). Healthcare professionals continue to work extended hours, often with limited access to personal protective equipment (PPE) (Nonprofit Quarterly, 15 January 2021). Their calls for better working conditions, greater COVID-19 protections, and a stronger government response to the crisis nationwide have all contributed to spikes in protests throughout the year, with surges during each wave of the pandemic.

These protests were soon followed by an escalation in coronavirus-related demonstrations over the health and safety of prisoners and detainees (in gray in graph above). In late March, hundreds of detainees held by US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) took part in a hunger strike to protest inadequate health precautions in detention facilities amid the pandemic. In some instances, guards punished detainees who participated in strikes (Buzzfeed News, 10 April 2020). Prisoners in state and federal correctional facilities have also demonstrated over health concerns as the virus spread within the prison system. Several organizations, including the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and Refugee and Immigrant Center for Education and Legal Services (RAICES), protested in solidarity with both groups.

Come April, trends in coronavirus-related demonstrations shifted to anti-restriction or ‘reopen’ protests (in teal in graph above; see inset box for definition), especially in the lead-up to expected reopenings in early May, during which nearly half of all US states began phased reopenings or were set to allow the expiration of stay-at-home orders. Demonstrators often voiced exasperation at the economic costs of combatting the pandemic, calling for a return to normalcy (NBC News, 1 May 2020). These demonstrations contributed to the first spike in coronavirus-related unrest during the earliest wave of the pandemic (see line graph at the beginning of this section).

May saw the height of the ‘Cancel the Rents’ movement organized in response to the eviction crisis (in navy in graph above). The movement was driven by those who lost sources of income amid the pandemic and faced potential eviction, especially as government financial support has been limited (Washington Post, 21 December 2020). The lapse of both a federal eviction moratorium and a $600-a-week supplement to unemployment benefits at the end of July contributed to a spike in demonstrations during the second wave of the pandemic (see line graph at the beginning of this section) (CNBC, 24 July 2020).

While the early summer was marked by a range of coronavirus-related demonstration drivers — with a mix of coronavirus-related demonstration drivers intersecting with racial justice organizing at the height of the BLM movement — the late summer and early fall saw a spike in coronavirus-related demonstrations around schools and education policy (in blue in graph above). The battle around school reopenings has led to surges in protests both for and against a return to in-person teaching. During the second wave of the pandemic, following the Trump administration’s call for schools to reopen for in-person teaching despite renewed concern over the coronavirus outbreak (New York Times, 23 July 2020), protests against reopening escalated (see line graph at the beginning of this section). Soon thereafter, before the official start of the school year, protests in support of reopening rose dramatically. More recently, during the third wave of the pandemic, protests for reopening schools — led by the ‘Let Them Play’ movement, advocating for the resumption of school sports — have again spiked (see line graph at the beginning of this section).

In the following sections, these demonstration drivers are explored in further detail.

Health Workers

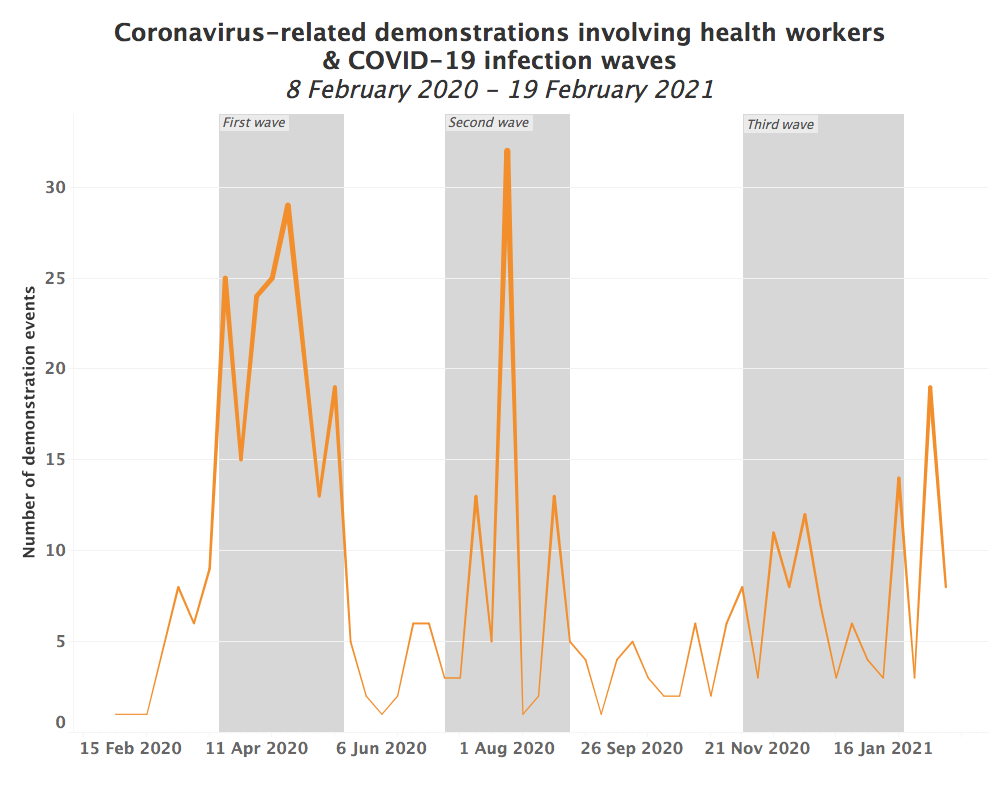

Demonstrations involving health workers emerged as the coronavirus began spreading in the early months of 2020 and have continued throughout the pandemic. Spikes in these demonstrations appear to be closely correlated with infection waves (see graph below). A first wave was reported across the US in the spring, immediately after the declaration of a state of emergency; a second wave was reported over the summer; and a third wave was reported at the end of the year, leading into the beginning of 2021. Health workers are directly impacted by each of these infection waves, as they drive patients to hospitals and healthcare facilities, and in turn drive demonstration patterns among health workers that mirror the same trends.

Since the start of the outbreak, health workers have consistently suffered from a shortage of PPE and excessive fatigue due to understaffing. Demonstrations held by health workers started from as early as February, when COVID-19 cases and deaths in the US were first reported (see graph above). They continued to gain momentum as health worker unions, including National Nurses United, played a leading role in voicing concerns over workplace safety and health protection (New York Times, 29 January 2021).

Health workers are regularly exposed to high risks of infection, and these risks have only increased as the number of patients seeking care surged nationwide, particularly during the peak of each wave. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), approximately 9,300 health workers contracted COVID-19 and 27 died during the early phase of the pandemic between 12 February and 9 April (CDC, 14 April 2020). The rapid rise in hospitalizations increased the demand for PPE, including hazmat-style suits, goggles, gloves, face shields, and N95 particle-filtering masks. With the government’s continued failure to meet the growing demand, health workers held demonstrations calling for mass production of PPE and appropriate government measures to stem further spread (Business Insider, 21 April 2020). In New York, health workers associated with the New York Nurses Association took legal action against the New York State Department of Health and local hospitals on 20 April for failing to provide adequate protection measures for health workers (New York Nurses Association, 20 April 2021). Additionally, ‘#GetMePPE’ rallies began trending online in March and soon developed into demonstrations in cities across the country, pushing the government to address the insufficient supply of protective gear for health workers (New York Times, 19 March 2020).

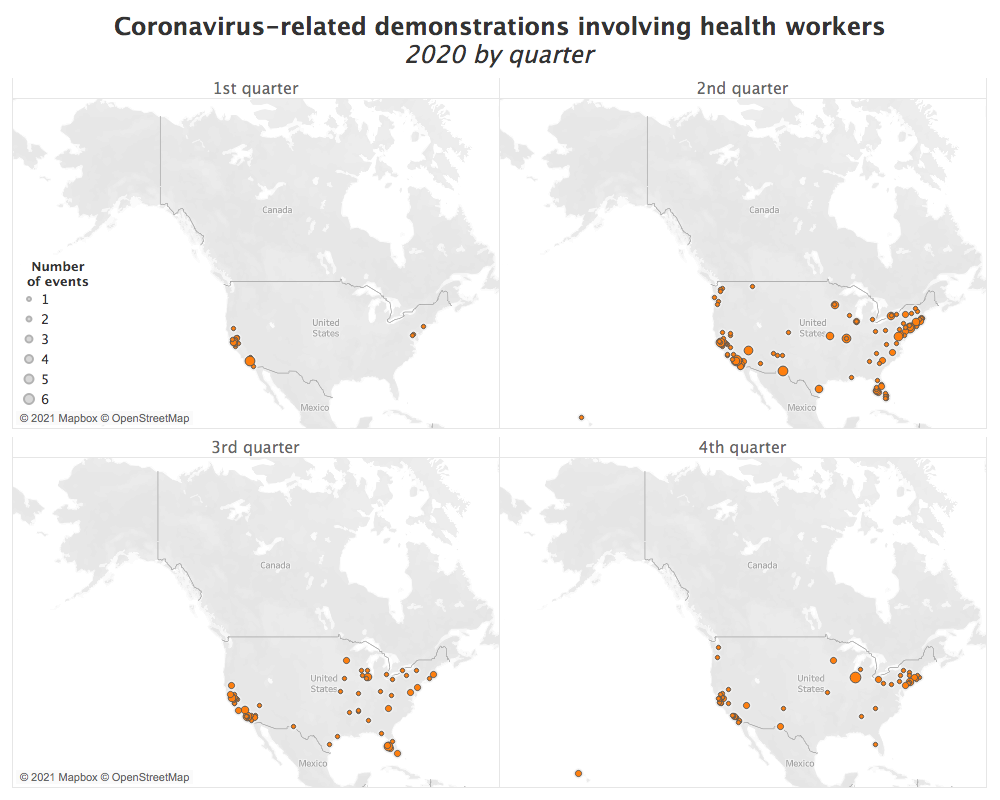

As the coronavirus outbreak in the US started in Washington and California with reports of the first cases and deaths (New York Times, 15 May 2020), so too did demonstrations (see map below). Health workers who immediately faced PPE shortages held demonstrations urging the government and hospitals to take greater precautions and provide better protection. Demonstrations soon spread nationwide as new COVID-19 cases began surging in eastern states, including New York, Massachusetts, and Florida (see map below). While demonstrations elsewhere have diminished through the end of 2020, health workers continue to hold significant demonstrations in California and New York. Health worker unions — including California Nurses Association and National Nurses United — have played a leading role in organizing and facilitating demonstrations in these states, respectively.

In addition to PPE shortages, increased workload — especially at the height of infection waves — has fueled further health worker demonstrations, especially in connection with excessive fatigue due to understaffing at hospitals (CNN, 11 November 2020). According to multiple surveys reported in November, at least half of all states were facing healthcare staff shortages, and more than a third of hospitals in states including Arkansas, Missouri, New Mexico, and Wisconsin were simply running out of staff (New Yorker, 15 December 2020). As the pandemic wears on, health workers have been spread even thinner, holding rallies calling for an end to extended working hours and underlining how extreme tiredness makes them more susceptible to infection (New York Times, 4 February 2021).

While health workers have called on the government for support, they have also taken to the streets to stand against demonstrators calling for the removal of government restrictions on businesses and schools, urging anti-lockdown demonstrators to comply with government stay-at-home orders and mask mandates (ABC News, 23 April 2020). With the pandemic prolonged in the US, health workers continue to face many of the same risks in their workplace more than a year later. As long as those risks persist, demonstrations by health workers will remain into the near future, likely to spike alongside spikes in infection rates.

Prisoners and ICE Detainees

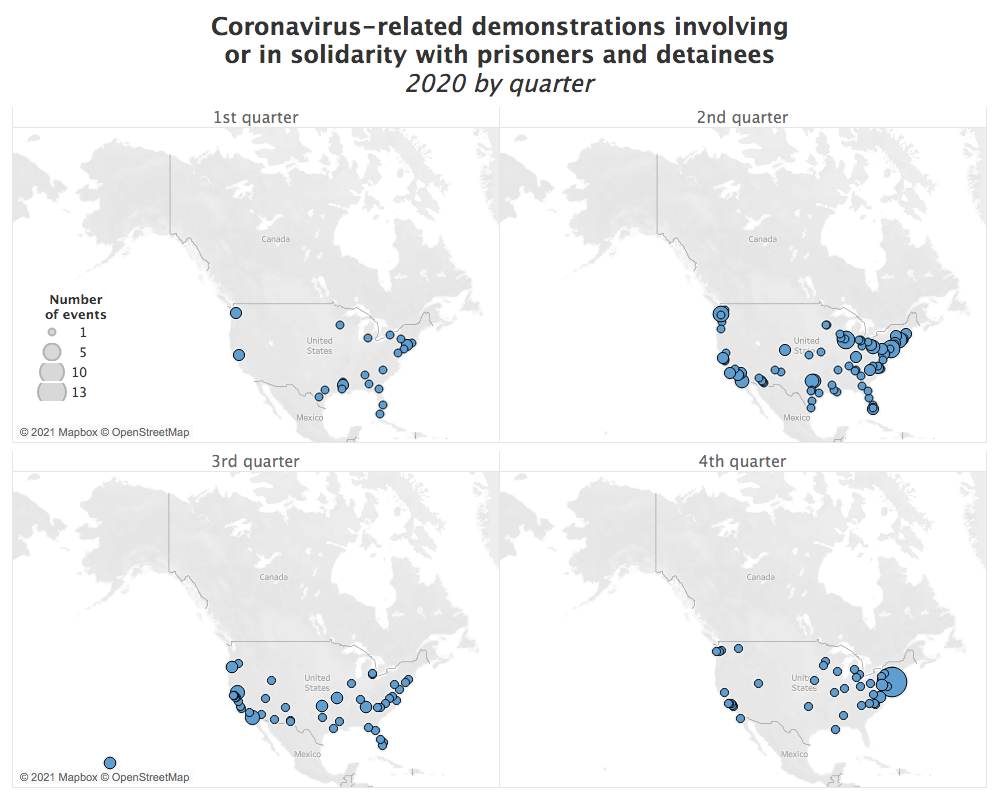

Demonstrations in support of and by prisoners and detainees began in March and have focused on the health of incarcerated people in the state and federal prison system, in addition to immigrant detainees in ICE detention centers. Incarcerated people worldwide are at high-risk of contracting the coronavirus due to a combination of cramped quarters, poor ventilation, limited time outdoors, and restrictive measures that prevent the use of masks and other PPE (Washington Post, 26 March 2020). In early April, for example, Chicago’s Cook County jail was the largest known source of coronavirus infections nationally (New York Times, 8 April 2020). By the end of April, over 80% of the inmates at the Marion Correctional Institute in rural Ohio had tested positive for the coronavirus (Dispatch, 25 April 2020). As of mid-February 2021, more than 381,000 prisoners have tested positive for COVID-19 — over 16% of the incarcerated population in the US — and more than 2,400 have died (The Marshall Project, 19 February 2021). In Arkansas, Kansas, Michigan, and South Dakota, more than half of all prisoners have been infected (The Marshall Project, 18 December 2020). Overall, the infection rate for prisoners in the US is over four times that of the general population (US News & World Report, 19 February 2021).

Due to the heightened risk of infection faced by incarcerated people, demonstrations in solidarity with prisoners and detainees have advocated for measures like early releases to reduce prison populations as well as improvements to sanitary conditions. The incarcerated have also attempted to bring awareness to infection risks and poor detention conditions through demonstrations inside detention facilities, calling on authorities to enforce more effective isolation policies in response to positive COVID-19 tests, for example. When such demonstrations fail to garner a response, some inmates have launched hunger strikes or riots.

Prison unrest increased along with the broader rise in public concern over the pandemic, which peaked in the late spring as stay-at-home orders became widespread. The earliest demonstrations by ICE detainees and state and federal prisoners calling for mass release or increased safety procedures began on 20 March at the Etowah County jail in Alabama and the Northwestern New Mexico Correctional Center (Washington Post, 25 March 2020; Albuquerque Journal, 21 March 2020). By 26 March, more than 350 ICE detainees began a hunger strike at the Stewart Detention Center in Georgia, after smaller hunger strikes at detention centers in New Jersey and Florida (Wall Street Journal, 27 March 2020; Gothamist, 19 March 2020; Miami New Times, 26 March 2020). By mid-April, demonstrations and hunger strikes by ICE detainees and incarcerated persons spread to California, Kansas, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Texas, Virginia, Washington state, and Washington, DC (see maps below).

The spike in protests by prisoners and ICE detainees eventually dissipated, however, and did not rebound to the same degree in the winter — possibly due to aggressive tactics by guards to discourage demonstrations and hunger strikes. In more than a third — over 37% — of peaceful coronavirus-related protests by prisoners and ICE detainees, guards have used force — including pepper spray and pepper balls — against demonstrators.

Nevertheless, the widespread use of repressive measures by correctional officers — in conjunction with insufficient policy changes — appears to have been ineffective in preventing demonstrations over a longer period. In St. Louis, Missouri, over 100 inmates rioted on 6 February 2021 and briefly took control of two units at the St. Louis Justice Center (Riverfront Times, 6 February 2021). The following day, a number of prisoners rioted and briefly trapped four correctional officers in a room at the Inverness Jail in Portland, Oregon after over 100 prisoners — more than one-fifth of the prison’s population — tested positive for the virus (The Oregonian, 8 February 2021). The riots occurred after officers violently repressed demonstrations by prisoners in St. Louis in January 2021 and December 2020, and ignored demands from prisoners in both cities for PPE, enhanced COVID-19 testing, and other protections from the virus (New Republic, 10 February 2021; CBS 6 Portland, 8 February 2021). The St. Louis Public Safety Director denies that the incarcerated populations in St. Louis correctional facilities are under any threat from the virus and called the prisoners “very violent and aggressive” (NBC 5 St. Louis, 6 February 2021).

The proliferation of demonstrations by incarcerated people has invigorated various activist groups concerned with detainee rights. Demonstrations by such groups peaked in the spring of 2020 and again in the winter. Throughout March and April, organizations like Never Again Action and RAICES held repeated demonstrations in support of ICE detainees in California, New Jersey, and Texas, occasionally co-occurring with activists in support of the Abolish ICE movement. In April and May, various organizations, including the ACLU, held several protests calling for the release of inmates amid the pandemic in over 30 states and the District of Columbia, with California and New York accounting for a third of these demonstrations (see map above). Such demonstrations often focus on subsets of prisoners, specifically those incarcerated for the inability to make bail, elderly inmates, those incarcerated for non-violent offenses, and ICE detainees.

As the summer progressed, demonstrations in support of prisoners and ICE detainees decreased in conjunction with lower infection rates and a surge in demonstrations calling for racial justice following the killing of George Floyd by police in May. Demonstrations associated with the BLM movement likely overlapped with those supporting prisoners as both are concerned with addressing systemic racism. Even accounting for a 34% decrease in the incarceration rate since 2006, Black Americans are incarcerated at over 5.5 times the rate of white Americans at the state level (Pew Research Center, 6 May 2020). Federally, the incarceration rate of Black Americans is still more than 3.5 times that of white Americans (Federal Bureau of Prisons, 12 February 2021). The ACLU, one of the most prominent organizations to demonstrate in support of prisoners in April and May, initiated at least 18 legal actions in support of the BLM movement between June and October (American Civil Liberties Union, 22 October 2020).

With the arrival of winter and the third wave of infections, however, demonstrations explicitly supporting prisoners and detainees recommenced, albeit at lower numbers than in the spring. The winter demonstrations continued to call for the release of inmates and also saw the first demonstration to call for inmates to receive vaccination priority on 29 December (WTNH, 29 December 2020). In Hackensack, New Jersey, people protested outside the Bergen County Jail multiple times per week in solidarity with ICE detainees on hunger strike and in support of the Abolish ICE movement. Largely due to the frequent demonstrations in Hackensack, New Jersey accounts for nearly a third of all reported demonstrations in support of releasing ICE detainees amid the coronavirus (see map above). Subsequent demonstrations calling for prisoner and detainees vaccinations have occurred in January and February 2021.

Despite the high risk profile of incarcerated people, Americans remain divided on the prospect of vaccinating them before the general public. Opposition to vaccination likely stems from a wider disregard for ensuring adequate healthcare for inmates that predates the coronavirus. Prior to the pandemic, prison healthcare was often inferior or nonexistent, lacked accountability, and was prone to severe cases of negligence (WBUR, 23 March 2020). Despite these problems, past research on public opinion indicates that people are more than four times as likely to believe that prison conditions should be made harsher rather than improved, likely contributing to neglect and inadequate spending (Criminal Justice Review, 9 April 2014). Limited access to the coronavirus vaccine for the general public has potentially further fueled this attitude. Those in opposition to vaccinating prisoners have often relied on the image of “country-club” prisons, alleging that “it might be tempting to say that crime pays as authorities are vaccinating federal prisoners across the country, while millions of law-abiding citizens can’t even get an appointment for the first dose” (ABC 7 Chicago, 22 January 2021). Democratic Governor Jared Polis of Colorado reneged on his state’s plan to vaccinate prisoners simultaneously with other high-risk populations after public outcry, saying that “there’s no way [the vaccine is] going to go to prisoners before it goes to people who haven’t committed any crime. That’s obvious” (Colorado Sun, 2 December 2020).

As of December, only seven states were prioritizing incarcerated people for vaccines, while about 20 states were prioritizing prison staff (NPR, 24 December 2020). By mid-January, at least 15 states initiated some form of vaccine distribution program to prisoners at correctional facilities and other states, such as Oregon, have since been ordered by judges to begin distribution of vaccines to prisoners (NBC News, 10 January 2021; CNN, 3 February 2021). Yet, the efficacy of these programs varies significantly as each state sets its own standards, often altering plans independent from the federal government and other states, such as in North Carolina (Carolina Public Press, 4 February 2021). Less than 2% of all inmates received vaccines by the end of January, compared to over 10% of the general population (The Guardian, 9 February 2021; New York Times, 16 February 2021). Conversely, in California, 40% of the prisoner population had received at least the first dose by late February, compared to 14.5% of the public (Los Angeles Times, 23 February 2021).

Moving forward, it is likely that Republicans will support bills that prevent prisoner vaccination plans wherever possible, as they have done in Wisconsin (ABC 2 Milwaukee, 17 February 2021; La Crosse Tribune, 21 February 2021). At the same time, a concerted push by journalists, health consultants, and activists around the country may bolster public support for vaccinating prisoners (New Yorker, 13 February 2021; Wichita Eagle, 18 February 2021). The competing pressures will most likely result in a piecemeal state-by-state approach to vaccination for prisoners, provoking demonstrations by supporters and opponents depending on which side appears poised to win.

Right-Wing Militarized Social Movements and Anti-Restriction Demonstrations

Anti-lockdown protests first began in March, but it was not until April that right-wing mobilization, especially involving militarized social movements like militias and street groups, began to organize massive national demonstrations. This coincided with nationwide “Operation Gridlock” organizing, the first substantial reactionary protest movement against COVID-19 lockdown measures. On 17 April, then President Donald Trump encouraged mobilization against pandemic-related restrictions, tweeting commands to “LIBERATE MINNESOTA,” “LIBERATE MICHIGAN,” and “LIBERATE VIRGINIA, and save your great 2nd Amendment. It is under siege!” (Detroit News, 17 April 2020).

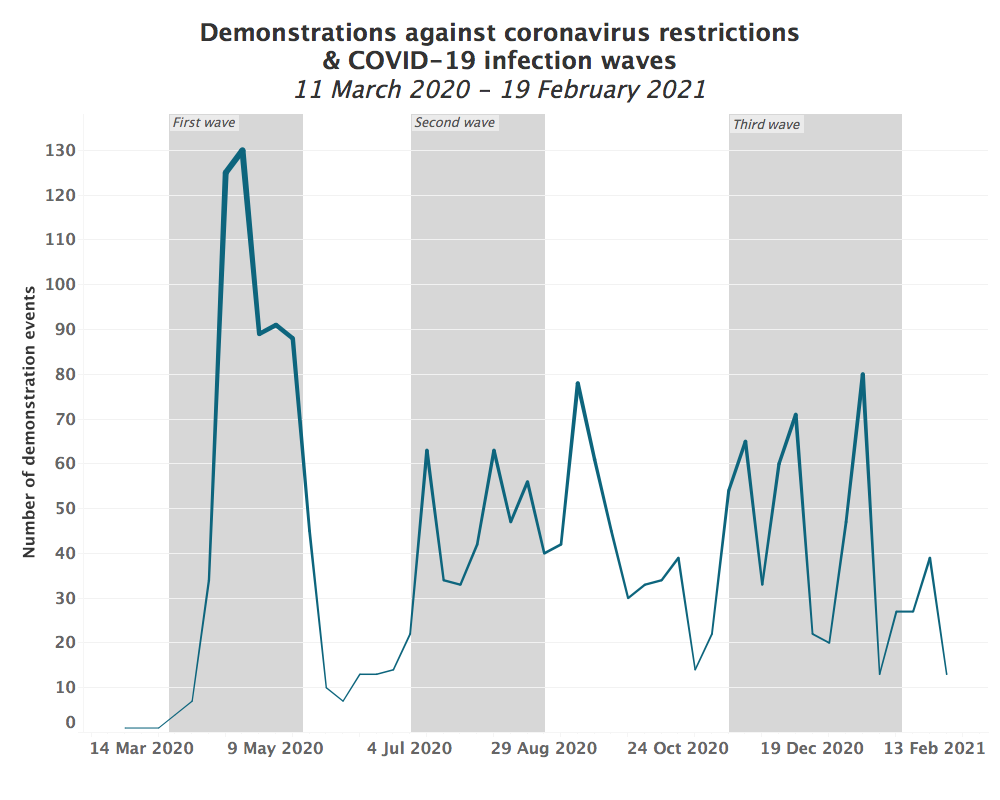

Although momentum behind the anti-lockdown protests waned in May, demonstrations rebounded over the summer and then spiked again in the fall and winter (see graph below). Right-wing mobilization against COVID-19 restrictions has tended to correlate closely with waves of infections, which themselves correlate with public health measures and more aggressive government efforts to curb the spread of the virus. As a result, anti-lockdown protests often come in waves as well, in direct response to new state restrictions aimed at addressing surges in COVID-19 cases.

Anti-lockdown protests are also likely driven by several other forces beyond public health measures alone. For example, in later periods last year, anti-lockdown demonstrators took the opportunity to air other grievances alongside reopen demands — such as those against ostensibly left-wing mobilization associated with the BLM movement over the summer, or against election results as part of the “Stop the Steal” movement (for more information on ‘Stop the Steal’ demonstrations and right-wing mobilization after the election, see this recent ACLED report). These types of contributing causes of protest are evident both in the mixture of flags and signs being waved at protests, as well as in rhetoric around such organizing throughout this period. These often took on local characteristics, such as supporting truckers in Oregon, calling for more militias to be formed in Virginia, defending Confederate monuments in Georgia, or denouncing the arrests of militia actors in Michigan. Right-wing mobilization briefly subsided around the holiday season before once more rising ahead of the certification of President Joe Biden’s electoral victory and coming to a fever pitch with the Capitol riot in January 2021. The crackdown on participants in the riot have since led to both new security measures and deplatforming efforts targeting right-wing organizations, suppressing right-wing mobilization from mid-January and into February. As it stands now, these movements have been largely stymied in the near term, but are almost certain to reactivate by the summer, if not before, driven both by the precarity created by COVID-19 lockdowns in the absence of financial assistance as well as opposition to the Biden policy agenda that begins to take shape.

Right-wing mobilization against COVID-19 restrictions has been a crucial way for far-right armed groups to build networks around the country. Rallies have provided locations for both unaffiliated individuals and organized groups to express their politics, connect, and establish coalitions. This trend has been driven by a confluence of important factors, the first of which, as mentioned above, is the proliferation of public health measures implemented by state bodies. These state actors are institutions of which many within the militia milieu are extremely skeptical, especially in recent years. The second is the usual demographics of militia group organizations, specifically that many are typically suburban and exurban middle class, white business owners, or otherwise members of the downwardly mobile middle class. This identity overlaps significantly with those most engaging in demonstrations against lockdown measures, due to the outsized short- to middle-term impacts of community closures on small business owners. Thirdly, as part of a nationally driven push, the “2A movement” had seen massive success in crowd turnout on 20 January 2020 following a call-to-action in Richmond, Virginia organized by the Virginia Citizens Defense League (VCDL). These types of organizing have given momentum to the intersection of militia and unaffiliated right-wing mobilization that would lead anti-lockdown demonstrations going into the first phase of the pandemic. The map below depicts where anti-restriction demonstrations have taken place around the country and where they have involved right-wing militarized social movements, such as militia groups.

The appeal of mass mobilization around the Second Amendment’s right to bear arms, demonstrated by the 20 January call-to-action, set an example for future mobilization, especially as anti-lockdown protests are often described not only as calls to reopen, but also as explicit or implied calls to ‘defend’ the right to bear arms — as seen in Trump’s tweets, noted above. The “2A movement” also extends beyond militias themselves, instead encompassing a broader movement of usually armed, pro-gun activists, including hobbyists, ‘Constitutionalists,’ and more. In fact, the first anti-lockdown protest involving right-wing militarized social movements recorded in the US was a demonstration in Richmond, Virginia on 31 March organized by the same VCDL. This event, styled as a protest against Governor Ralph Northam’s order to close indoor shooting ranges, was likely critical for channeling momentum around “2A” activism towards anti-lockdown demonstrations.

Like with the 20 January and 31 March gatherings in Richmond organized by the VCDL, anti-lockdown protests have been characterized by a coalescence of previously disparate, armed, right-wing groups alongside a range of other right-wing movements that are typically not equipped with firearms, such as the Proud Boys. Such concerted cooperation is relatively new on this scale, though there are some antecedents in past years, such as the Timber Unity protests in Washington state starting in 2019 (OPB, 6 September 2019; MilitiaWatch, 14 July 2019). Last year’s ‘reopen events’ brought together new coalitions connected to street activism, thereby setting the stage for future engagement that has characterized the remainder of 2020 and the start of 2021. These protests, like the Timber Unity movement of 2019, may also have been taken over by Republican political elites and financiers at both the local and national level after gaining steam through earnest mass mobilization (Willamette Week, 7 August 2019; CNBC, 13 January 2021).

ACLED tracked the activities of more than 140 right-wing militarized social movements in 2020, including a range of militia and other far-right mobilization throughout the year. Analysis of these data and key trends among right-wing mobilization presents a long arc of organizing history. Militia groups and right-wing social movements — like ‘Stop the Steal’ — draw much of their contemporary momentum directly from anti-lockdown mobilization taking off in April 2020. For example, some members of the Michigan-based Wolverine Watchmen militia group, arrested for their roles in the plot to kidnap Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer, were directly involved in anti-lockdown protests and other “2A” rallies in their state. Multiple arrestees in that plot also played leadership roles in the Michigan Liberty Militia, which itself has been a staple at anti-lockdown, “2A,” and other right-libertarian gatherings across Michigan. Court documents indicate that, while standing on the steps of the Michigan Capitol as they attended one of these protests, several Michigan Liberty Militia members discussed their plans to execute members of the Michigan state legislature on live TV (WWMT, 12 November 2020).

This type of aggressive rhetoric or planning at reopen protests was not limited to Michigan alone. At an Illinois reopen protest, a local militia leader told a journalist his demand for politicians: “Re-open my state or we will re-open it ourselves” (BBC, 21 April 2020). A Three Percenter group hung an effigy of Kentucky Governor Andy Beshear outside of the governor’s mansion in Frankfort in May (CNN, 25 May 2020). That same month, reopen protesters in North Carolina brought all manner of weaponry, including an inert AT-4 rocket launcher, to their demonstration in Raleigh (Business Insider, 11 May 2020). In Georgia, ‘Stop the Steal’ demonstrations involved a variety of overlapping and integrative movements — from as institutionally formalized as elected GOP politicians, to as heavily armed as local III% movements, to as openly fascist as the Groyper Army/America First coalition. These ‘Stop the Steal’ protests garnered visits or support from Ali Alexander of the official ‘Stop the Steal’ PAC; InfoWars founder Alex Jones; and former Kyle Rittenhouse fundraiser, libel lawyer, and Q-Anon adherent Lin Wood (It’s Going Down, 24 November 2020). In some cases, attendees also protested coronavirus mask mandates, with some wearing masks to make fun of those who follow mask rules. These gatherings became weekly fixtures in downtown Atlanta, until the end of a ‘Stop the Steal’ rally involving multiple militia groups resulted in a dozen or so militia members carrying weapons to assault unarmed counter-demonstrators in an Atlanta alleyway (WABE, 22 December 2020). A week later, New York Watchmen — including a New York-based member of the III% Security Force group that was involved in the Atlanta assault — attacked counter-demonstrators at a 19 December reopen demonstration in Buffalo, New York. These attackers broke the ribs of a demonstrator who was part of a memorial for those who had died of COVID-19 (WGRZ2, 19 December 2020).

Nearly a quarter — over 23% — of all demonstration activity involving right-wing militarized social movements across the US since the start of 2020 has been organized in opposition to pandemic-related restrictions imposed by state governments. While these groups have engaged in just 4% of the total number of demonstrations against COVID-19 restrictions recorded in the country, their involvement has increased the risk of violence and destructive behavior: anti-restriction demonstrations involving militias and other militarized social movements turn violent or destructive over 55% of the time, relative to less than 4% of the time when these groups are not present (see graph below).

More than just a means to express opposition, reopen protests also provided useful protest modalities for other violent far-right groups to replicate. Given the mobilization of right-wing actors that COVID-19 lockdowns prompted, more opportunistic movements also found common cause with militia groups with whom they were not usual compatriots. Others saw opportunities to exploit the pandemic to advance their wider goals. The Boogaloo Boys — a neo-dadaist, armed movement based on a far-right meme about the Civil War — saw these gatherings as an opportunity to escalate tensions with the government, for example. With varying levels of success, Boogaloo cells and individuals attempted to form new working relationships with Proud Boys; state-level militia groups like the Michigan Liberty Militia; the “2A” community; and in some cases even groups describing themselves as part of the BLM movement (Bellingcat, 27 May 2020; SPLC, 5 June 2020). This is part of the reason why Boogaloo adherents are visible at many reopen protests, which were often framed as demonstrations against ‘tyranny.’

The way that militia groups engaged with demonstrations in early 2020 became a pattern for the months that followed. In some cases, militias have shown up as ‘security’ — similar to trends later seen in response to protests associated with the BLM movement (NBC News, 1 September 2020; Triad City Beat, 3 June 2020). In other cases, they have become involved as groups or representatives of groups to engage in demonstrations themselves (Triad City Beat, 1 May 2020; Newsweek, 18 September 2020). In other cases still, these groups have participated in the direct organization of events or claimed events as ‘their’ action, sometimes in response to unsubstantiated rumors (Washington Post, 4 July 2020). Many militias assert that they are apolitical bodies or solely defensive organizations, but the involvement of many of these groups in highly politicized and sometimes offensive maneuvers often run counter to these claims. Many of these groups are staunchly pro-Trump, and others have frequently directly threatened those they oppose (Talking Points Memo, 28 October 2020; The Nation, 29 October 2020; Refinery29, 9 December 2020).

Organizing alongside other right-wing activist movements has allowed militias, militant groups, and social movements to develop networks for future mobilization. In many cases, external call-to-action style events have led to these disparate movements finding further common cause, which in turn led to future engagements through these networks. For example, in Michigan, multiple armed far-right groups — from the Michigan Liberty Militia to the Proud Boys and Boogaloo adherents — joined for a series of “Patriot Rallies” organized by the American Patriot Council, itself a protest organization started by a local conservative government official (Times Herald-Record, 23 October 2020). These include gatherings on 14 May, 18 May, 18 June, 27 June, 17 September, and more. These protests carried such titles as “A Well Regulated Militia,” “Sheriffs Speak Out,” or, more ominously, “Judgment Day.” Most targets of these types of demonstrations were those associated with ‘progressive’ causes, be that public health lockdown measures, the removal of Confederate statues, or gun restrictions.

While much attention is currently focused on the role that militia groups, such as the Oath Keepers, played in storming the US Capitol in January 2021 (New York Times, 29 January 2021; CNN, 12 February 2021; Fox News, 27 January 2021), militias and other aligned right-wing actors have been conducting similar operations at state capitols for some time. These operations can employ several different levels of force: from the aggressive storming of the Michigan State Capitol in Lansing in April 2020 (Guardian, 30 April 2020), to more leisurely gatherings inside state capitol buildings like in Frankfort, Kentucky in January 2020 (Rolling Stone, 1 February 2020).

For example, on the first day of the new year, about 100-200 people gathered at the Oregon State Capitol for a ‘Mass Civil Disobedience’ rally, marching to the governor’s mansion in Salem in support of reopening Oregon, as well as against alleged voter fraud in the 2020 presidential election. The event was organized by Oregon Women for Trump, with some attendees armed. Patriot Prayer, the Proud Boys, and unidentified militia groups also attended the rally. The demonstrators were met with a small group of self-identified Antifa members, some of whom were armed, who had gathered for a ‘Fascist Free 503’ demonstration in Bush’s Pasture Park in support of the BLM movement and against police brutality. At one point, members of the Proud Boys — armed with bats, paintball guns, and firearms — broke off from the group to confront the Antifa demonstrators nearby, with fighting then erupting between the groups. Police intervened, using non-lethal munitions to quell the unrest, though they were met with physical resistance and smoke grenades from the Proud Boys. Mere days later, another demonstration took place at the Oregon State Capitol. The event was again organized by Oregon Women for Trump, with Patriot Prayer and Proud Boys members present. They again engaged in altercations, this time with BLM supporters, in which they burned an effigy of Oregon Governor Kate Brown because of her coronavirus restrictions (Yahoo!, 6 January 2021).

Such demonstrations have continued across the country in the new year. In the days following the events noted above in Salem, roughly 100 Trump supporters, including members of the Three Percenters, gathered in front of the Minnesota State Capitol in Saint Paul to protest the results of the 2020 election and the coronavirus restrictions put in place by the governor. Some of the protesters carried guns. While State Patrol officers guarded the steps of the capitol building, they did not intervene in the protest. On the same day, about 100 heavily armed people, including members of militias like the Three Percenters and the III% United Patriot Front, gathered outside the Kentucky State Capitol in Frankfort for a ‘Stop the Steal’ rally in which protesters expressed opposition to Governor Beshear’s executive orders to combat the coronavirus pandemic. Days later in Austin, Texas, a number of armed protesters, members of the Texas Militia, members of local Tea Party chapters, and the head of the Texas GOP gathered outside the Texas State Capitol to protest business shutdowns during the pandemic and to express support for then President Trump. Members of the Southern Patriot Council group were also there to protest against gun control measures and to express support for the rioters who stormed the US Capitol on 6 January. While Texas troopers and Texas National Guard were stationed at all entrances of the capitol, they did not engage with the protesters.

In fact, all 50 states saw right-wing movements protest outside of their state capitol buildings or governor’s mansions over the course of 2020 and into early 2021. In four states — Kentucky, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Utah — right-wing demonstrators, some armed, entered the state capitol buildings. In at least seven states — Georgia, Indiana, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, and North Carolina, and Washington — right-wing demonstrators protested outside of governor’s mansions. In North Carolina, one individual was arrested for attempting to break into the mansion. In Washington, neo-Nazis and militia members both shouted from outside the windows of the governor’s mansion after a ‘Stop the Steal’ crowd breached the gates to the compound (Seattle Times, 6 January 2021). Georgia and South Dakota experienced only post-election right-wing protests at their state capitol buildings, rather than pre-election organizing. Notably, Georgia drew a sizable coalition of far-right actors to downtown protests in Atlanta around the ‘Stop the Steal’ movement, including multiple Three Percenter gatherings, Nick Fuentes’ Groyper Army, the Proud Boys, Alex Jones’ InfoWars, and more (Newsweek, 18 November 2020). That all US state capital cities saw right-wing demonstrations at their capitol buildings underscores the extent of mobilization before, during, and beyond the election period.

These events are important markers of organizational and mass mobilization crescendos, built out of months or even years of more clandestine organizing. The Wolverine Watchmen plot, for example, predates the storming of the Michigan Capitol in Lansing (Business Insider, 16 October 2020). While federal and state charges in that case may have prompted increased media attention on the militia groups that the Wolverine Watchmen organized alongside, anti-lockdown protests likely accelerated the Wolverine Watchmen’s planning (Business Insider, 2 November 2020). While protests such as the VCDL Lobby Day in January were looked to as massive successes early in 2020, those like “Operation Gridlock” in April helped re-energize and realign public, right-wing mobilization. Since 6 January 2021, and especially since the crackdown on those involved in storming the US Capitol building, many activists and groups have gone underground. These networks are almost certain to evolve and reactivate later in the year when the next politically salient moment approaches. This mobilizing event or trend could be sparked by any number of developments, from Biden pursuing gun restrictions or a mandatory vaccination regimen or mask mandate, to some new far-right conspiracy theory. Mobilization around the former is already beginning to re-emerge: on 20 February, RidersUSA organized a ‘Right to Keep and Bear Arms Rally’ outside of the state capitol in Phoenix, Arizona in support of the Second Amendment. The demonstration was attended by approximately 1,200 people, including Three Percenters and other armed individuals.

Evictions

Not long after the start of the coronavirus outbreak, the pandemic’s economic fallout led to a nationwide unemployment and eviction crisis. Approximately 16.5 million renter households lost income due to the pandemic within the first few months (Terner Center for Housing Innovation, 24 April 2020). By the summer, about a third of renters failed to make payments to their landlord in full and on time (The Atlantic, 2 May 2020; CNBC, 6 August 2020). As a result, demonstrations against evictions spiked in April and May as government financial aid, including the federal eviction moratorium and $600-a-week unemployment benefits, was set to expire on 25 July (Forbes, 24 July 2020). The ‘Cancel the Rents’ movement has been at the center of nationwide demonstrations calling for the cancellation of rental payments and the suspension of mortgage payments during the pandemic (Bloomberg, 29 April 2020).

With surging unemployment amid early state lockdown measures, the US economy slid into a sharp downturn by March 2020 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 8 June 2020). Real GDP declined by approximately 31% in the second quarter of 2020 due to stay-at-home orders issued in the spring (The Bureau of Economic Analysis, 30 September 2020). The economic downturn put an end to 113 straight months of job growth (Brookings Institute, 17 September 2020), and unemployment peaked in April at 14.8% — approximately four times higher than it was in January (US Bureau of Labor Statistics, 17 February 2021). Small business was hit especially hard: around 100,000 small businesses had to shut down permanently by early May (Washington Post, 12 May 2020).

In an effort to alleviate the economic recession, the federal government strived to provide coronavirus relief packages beginning in March 2020. The first stimulus bill, or Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, was to provide the total amount of $2.2 trillion, the largest economic stimulus package in US history (New York Times, 25 March 2020). Government pandemic assistance payments were distributed to households, small businesses, companies, and health workers, among others. The second round of relief came in late December 2020, as debates over the size of the package were held up in Congress (New York Times, 28 December 2020). As President Biden took office, he planned to provide a $1.9 trillion relief package in the early months of 2021 (New York Times, 17 February 2021).

While the government has grappled with the pandemic-stricken economy, the country has been gripped by nationwide housing instability and the threat of mass evictions. Although the CDC issued a temporary moratorium on evictions on 4 September (Federal Register, 4 September 2020), it instantly faced pushback from tenants due to the ambiguity of the order, which still gave landlords the ability to evict (Washington Post, 27 October 2020). State government approaches to eviction protections have varied from state to state, increasing confusion about guidelines (Washington Post, 29 April 2020). In addition, several states created new bureaucratic hurdles: in Arizona, California, Florida, Kansas, Maryland, New Mexico, Nebraska, and Utah, tenants must demonstrate that they have been affected by the pandemic in order to be safeguarded from evictions. However, many renters have struggled with demonstrating their economic hardship in correlation with the coronavirus pandemic in courts due to the ambiguity of state guidelines (Bloomberg, 11 February 2021). Some judges tend to interpret the moratorium order in a broader sense, so that eviction agencies can stop evictions as a public health measure, while other judges have taken a narrower view, strictly following the order’s five-point description of who is covered (NBC, 14 February 2021). In two Georgia counties, judges have refused to acknowledge the order altogether (Atlanta Journal-Constitution, 8 February 2021).

The damaging effects of evictions amid the coronavirus pandemic have exacerbated long-standing racial inequalities in the US. As Black and Latinx households are twice as likely to rent as white households, the early wave of evictions disproportionately hit them hardest (Politico, 15 December 2020). Historically, homeownership has been tied to significant racial and ethnic disparities (Center for American Progress, 7 August 2019) — about 70% of the white population owns their home, whereas only about 40% of the Black population does (US Census Bureau, 2019). Consequently, the emergence of the eviction crisis has become a particularly serious threat to communities of color (Center for American Progress, 10 June 2020). Accordingly, demonstrations calling for an immediate halt to evictions erupted in states with racially diverse populations, such as California and New York, which was home to the highest number of anti-eviction events. Despite the eviction ban, some landlords in California reportedly tried to evict renters by “locking them out of their homes, turning off their utilities and deploying other illegal methods” in predominantly Black and Latinx neighborhoods of Los Angeles (LA Times, 18 June 2020). In New York, over a half of Black households fell behind on rent between May and June (Community Service Society, 22 June 2020).

Demonstrations during the eviction crisis have fluctuated in line with federal and state eviction ban measures (see graph below). An early surge of the coronavirus-related demonstrations associated with evictions in the spring was attributed to discontent with the federal government’s handling of the eviction crisis. Although President Trump announced an eviction moratorium for single family homeowners for 60 days on 18 March (Department of Housing and Urban Development, 18 March 2020), the temporary remedy was insufficient in helping alleviate the concerns of renters as the relief program was limited to Federal Housing Administration (FHA)-insured single family homeowners (NBC, 21 March 2020). Another surge of demonstrations took place during the summer, until the CDC announced the eviction moratorium on 1 September (Federal Register, 4 September 2020) (see graph below). While there was a decline after the moratorium was introduced, demonstrations around evictions resurged in the winter as the eviction ban was scheduled to expire on 31 December, then extended to 31 January 2021 (Business Insider, 28 December 2020) (see graph below).

The economic impact of the pandemic has served as a catalyst in pushing people towards participation in demonstrations. According to survey research, people who lost money or jobs due to the pandemic were more likely to participate in protests, specifically to register their discontent with the government (Washington Post, 5 August 2020). This discontent in turn fueled protests over the summer, including those in conjunction with the BLM movement. About 9% of demonstrations associated with the ‘Cancel the Rents’ movement have been held in conjunction with BLM.

On his first day of office, President Biden extended foreclosure moratoriums for federally guaranteed mortgages that were about to expire to 31 March 2021 (White House, 20 January 2021). In February, he announced relief programs for people at greatest risk of evictions and extended the foreclosure moratorium through 30 June 2021 (White House, 16 February 2021). Nevertheless, loopholes in these programs still put renters at risk of eviction: the executive order allows landlords to choose not to renew a lease and does not preclude them from filing for eviction. In addition, renters are required to provide their landlord with a signed copy of the CDC declaration to avoid eviction, which might be challenging for those who have no internet access or immigrant families for whom English is not their first language (USA Today, 2 February 2021). In late February, a federal judge in Texas ruled that the CDC eviction moratorium is unconstitutional, raising further concerns over the federal government’s ability to address the crisis (NBC, 26 February 2021). In consequence, the eviction crisis is expected to remain a salient driver of demonstration activity, at least in the short term, until the government fills existing policy gaps. Mobilization will likely surge as federal and state eviction bans near their expiration dates.

Schools and Education Policy

The debate over in-person teaching and education policy during the pandemic continues to drive demonstration activity as the Biden administration struggles to define and implement its 100-day plan to safely reopen schools (CNN, 11 February 2021). Although the issue predates the new administration, with demonstrations beginning over the summer and occurring throughout the fall and winter, President Biden emphasized the importance he placed on reopening schools by signing the “Supporting the Reopening and Continuing Operation of Schools and Early Childhood Education Providers” Executive Order on his first full day in office (Federal Register, 21 January 2021). The CDC released guidelines a month later, on 12 February, for safely reopening schools that lessened the ambiguity derived from contrasting CDC guidelines and statements by federal officials, including former President Trump (Center for Disease Control, 12 February 2021; NPR, 8 July 2020). Still, these new guidelines fall short of mandating policy changes desired by groups like teacher unions for issues including teacher vaccine requirements, and have been criticized by Republicans for lacking substantive changes to previous guidelines (USA Today, 12 February 2021).

Demonstrations focused on schools account for about a quarter of all coronavirus-related demonstrations in the US. Approximately two-fifths of these demonstrations have been organized against the reopening of schools (i.e. for continued online learning) while about three-fifths have been organized in favor of reopening (i.e. for in-person teaching). Both movements have been widespread geographically, with 43 states and Washington, DC hosting demonstrations against reopening and all but Arkansas and Washington, DC hosting demonstrations in support of reopening (see map below). Arkansas reopened schools for business-as-usual before the fall term commenced, which explains the lack of demonstrations in support of reopening schools (AP, 5 August 2020).

The long-term consequences of distance learning are dire. About 30% of K-12 students, disproportionately BIPOC students, lack access to the required technology for distance learning (CNBC, 12 August 2020). Even with adequate access to technology, many low-income families have struggled to meet other requirements of online learning, including providing physical space to work and telecommunicate in private, technical skills, and educational support amid the economic downturn (Yale School of Medicine, 29 May 2020). Some estimates indicate that Black students on average may be 12-16 months behind in math education if schools remain closed for 12 months — until June 2021 — while white students would lose 5-9 months (McKinsey & Company, 8 December 2020). BIPOC students are also disproportionately located in areas that have been the hardest hit by the coronavirus — low-income, urban settings — meaning they are most likely to remain online for extended periods (The ANNALS, 25 October 2017). Schools with high concentrations of students living in poverty are almost twice as likely to remain closed compared to schools with low concentrations (PBS, 25 November 2020). In New Jersey, the majority of Black and Latinx students, representing disproportionately low-income communities, were required to distance-learn as of October 2020, whereas less than one-third of white students were required to distance-learn (PBS, 25 November 2020).

Notably however, concerns over these wealth and racial inequalities are typically absent from demonstrations surrounding school reopenings. This may be partly due to parental concerns over school safety — 79% of Black parents and 72% Latinx parents believed that returning to school was unsafe as of August 2020, while only 43% of white parents felt the same — underlying historic trends in racially biased public funding for schools (Washington Post, 6 August 2020; The Atlantic, 30 September 2015). Such concerns also highlight disparities in infection and survival rates between racial groups, as the coronavirus has disproportionately affected the lives of BIPOC communities (NPR, 30 May 2020). A combination of protest fatigue and the rise of other social movements — such as the BLM movement, which targets systemic racism on a larger scale — could also be contributing factors.

In addition to BIPOC families, women have also been disproportionately affected by the pandemic’s impact on schooling. Many women have left the workforce to manage competing demands at home amid the health crisis (Washington Post, 6 November 2020). In September 2020, as the new school year began, over four times as many women dropped out of the workforce in comparison to men (NPR, 2 October 2020). Overall, 2.3 million women have left the labor force since February 2020, reversing more than three decades of labor force gains in the span of a single year (Fortune, 5 February 2021). Studies also estimate that the gender wage gap will widen by 5% due to the pandemic (National Bureau of Economic Research, August 2020). These costs are especially borne by women of color, who disproportionately work in low-income jobs that cannot be transitioned to remote work. Nearly two-thirds of Latinx women and the majority of Black women earn low wages, compared to two-fifths of white women (Brookings Institute, October 2020). The effects on low-income communities, BIPOC individuals, and women are likely to reverberate for decades as a generation of students falls behind and women struggle to regain their former standing in the labor force. The Biden administration labeled these concerns a “national emergency” in early February 2021 (CBS News, 8 February 2021).

While the immediate need for relief may impact individuals who choose to demonstrate, it has been noticeably absent from the demands of protesters. Demonstrations calling for schools to reopen have, at times, made more specific demands in addition to advocating for in-person teaching: 30% have particularly called for school sports to resume, for example. Many of these protests have occurred alongside demands to reopen the economy or specific industries, and are attended by a mix of disparate groups. Protests to reopen schools began in earnest after the commencement of the school year in the late summer and early fall before trailing off later in the fall. They spiked again around the time students would traditionally return to school following winter break in the new year (in brown in graph below). The most recent spike in 2021 was largely a result of ‘Let Them Play’ rallies in California on 15 January, in which parents, student-athletes, and coaches called for the resumption of high school sports with no-to-minimal restrictions.

In contrast, calls for keeping schools closed have predominantly been organized and attended by teachers, peaking before the start of the fall term during the summer of 2020 (in navy in graph above). Nearly 80% of these demonstrations have been held by teachers, while the remainder have predominantly involved students. There is significant overlap between the two groups: more than half of the demonstrations involving students occurred alongside teachers.

Teacher activism against reopening schools is also linked to deeper concerns over safety, with mobilization reaching its peak at the height of the second wave of the pandemic. In July, more than 75% of teachers surveyed nationwide expressed concern over returning to in-person education, with about 33% stating that it was somewhat or very likely they would quit if forced to return to in-person education (Education Week, 24 July 2020). Although school deaths from the coronavirus are notoriously difficult to track and no database of teacher deaths exists, multiple cases have been reported since the beginning of the pandemic (New York Times, 27 January 2021). In Georgia, for example, two teachers died on 21 January 2021 from COVID-19 complications, prompting demonstrations by educators in support of closing schools or providing more protection for educators, such as vaccines (NBC News, 22 January 2021).

The Georgia state government, however, has gone in the opposite direction. On 27 January, state officials raided the largest vaccine distribution center in Elbert county for providing vaccines to teachers, removing vaccine doses and placing the center on a distributive hold until 27 July (Atlanta Journal-Constitution, 29 January 2021). According to Georgia’s Vaccination Plan, the state does not define teachers as high-risk essential workers or a “critical population,” relegating educators without existing preconditions to Phase 3 of the vaccine rollout (Georgia Department of Health, January 2021). Currently, 26 states and Washington, DC include teachers as eligible for early phases of vaccine distribution, but local distribution varies widely and, although they are eligible, educators may find vaccines difficult to obtain in their area (CNN, 5 February 2021; CBS 8 San Diego, 9 February 2021). Moving forward, it is likely that teachers will be given priority to receive vaccinations in line with President Biden’s 100-day plan, but it is unlikely that vaccinations for educators will be required to reopen schools in any state. Dr. Anthony Fauci, President Biden’s chief medical adviser and head of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, recently asserted that requiring teacher vaccinations to reopen schools is “non-workable” (Politico, 17 February 2021). Under such an outlook, demonstrations by educators calling for immediate vaccinations are expected to continue, though most other demonstrations related to reopening schools will likely decline.

Conclusion

Although 2020 came to a close with hope that the vaccine would bring the pandemic to a swift end, the rollout has been plagued by delays. While the new Johnson & Johnson one-dose vaccine has now been approved for use (Bloomberg, 27 February 2021), vaccine supplies remain limited. Only 20% of adults have been vaccinated as of February 2021, with many states falling short of even that rate (Forbes, 27 February 2021). While COVID-19 cases and deaths have declined, the infection rate is still 2.5 times higher than it was during summer 2020, and cases have recently stopped falling in what the CDC called “a very concerning shift in the trajectory” (NBC, 26 February 2021). A year after the national emergency declaration, some states continue to report record deaths in a single day (11Alive, 12 February 2021). Even as states like Texas have started lifting mask orders and other pandemic-related restrictions (AP, 2 March 2021; ABC News, 14 February 2021), the head of the CDC has warned that mask mandates should remain in place (Politico, 14 February 2021). New variants of the virus — thought to be more easily transmissible and to be associated with higher morbidity — have been detected (Bloomberg, 14 February 2021), raising fears that these mutations may not be stopped by vaccine or past-infection immunity (Washington Post, 9 February 2021). Such trends suggest that the pandemic may be far from over.

The full picture of the Biden administration’s response to the crisis — and its impacts on pandemic-related protest patterns — remains to be seen. If the government is able to meet Biden’s promise that vaccines will be available to all Americans by the end of May 2021 (NPR, 3 March 2021) and keep to his commitments to move teachers “up the hierarchy” for vaccination, then a return in most schools to in-person teaching may occur within 100 days (Guardian, 16 February 2021). As a result, teacher-led demonstrations and school-related protests will likely decline. If infections and deaths continue to drop as a result of the vaccination rollout, demonstrations organized by health workers may follow suit. The country could begin to reopen, allowing the economy to rebound and alleviating some pressure on renters. This could lead to a decrease in both anti-lockdown and anti-eviction mobilization. Prisoners and detainees will continue to suffer the worst of the pandemic, but the administration could take new steps to ensure they are not relegated to the bottom of the vaccination hierarchy (US News & World Report, 19 February 2021).

At the same time, much of the population remains resistant to vaccination, which could stymie efforts to combat the virus and reopen the country. Although support for the vaccine has grown in recent months (WebMD, 7 December 2020), a survey found that nearly “1 in 3 people in the United States said that they definitely or probably will not get the COVID-19 vaccine” as of early February 2021 (The Hill, 10 February 2021). Notably, this resistance extends to healthcare workers: Ohio’s governor stated in December that approximately 60% of the state’s nursing home staff have declined the vaccine, while New York’s governor has said he expects 30% of his state’s healthcare workers to do the same (New York Magazine, 4 February 2021).

If partial vaccination prevents a sustained decline in new COVID-19 cases, or enables a future resurgence, it could prolong lockdown restrictions, prompting an increase in reopen protests. Prolonged lockdowns will do additional harm to the economy, which will fuel further unrest over the eviction crisis as well as demonstrations calling for financial support.

However, if the administration responds with a mandatory vaccination policy or imposes new national restrictions to curb the pandemic, it could reinvigorate right-wing mobilization, including militia activity, against the federal government. While right-wing organizing and militia activity has temporarily subsided amid the crackdown on groups and individuals connected to the Capitol riot, these networks — bolstered during reopen rallies throughout 2020 — are expected to reactivate when the next politically salient moment arrives. The ‘anti-vax’ movement could serve as such a catalyst, as anti-vaccine activists are already a growing force at reopen demonstrations (New York Times, 4 May 2020), and have increasingly found common cause with right-wing anti-lockdown demonstrators as they shift their focus to the vaccination rollout (New York Times, 6 February 2021). Many of these demonstrators are new to the ‘anti-vax’ movement, joining as a reaction to the coronavirus pandemic and what they perceive as an attack on civil liberties mounted by the government in response to the health crisis (New York Times, 6 February 2021). In January, for example, reports indicate that an anti-vaccination protest in Los Angeles that temporarily disrupted operations at Dodger Stadium (one of the largest COVID-19 vaccination sites in the country), was connected to right-wing mobilization. On social media, organizers advised protesters to “please refrain from wearing Trump/MAGA attire as we want our statement to resonate with the sheeple. No flags but informational signs only” (ABC7, 30 January 2021). Earlier that month in California, “a group of women threatened lawmakers at a budget hearing at the [State] Capitol, telling senators that they were ‘not taking your [COVID-19] shot’ and that they ‘didn’t buy guns for nothing’” (New York Times, 6 February 2021).

A year into this national emergency, months after an attack on the seat of government, the US is at a crossroads. How the country reacts to these new pandemic and political phases will present a clear signpost for the future of political violence and protest in America.