In India, over 500,000 students signed up for the government-sponsored nationwide ‘Cow Science’ exam this year, which was scheduled for 25 February 2021. The ‘Cow Science’ exam, a free-of-cost voluntary exam, was purportedly meant to test people’s knowledge about cows, thus furthering curiosity about cows among the public (CNN, 8 January 2021). After widespread criticism of the course material, the exam, a product of the National Cow Commission or the Rashtriya Kamdhenu Aayog (RKA), was indefinitely postponed (Scroll, 22 February 2021). Scientists and educational institutions questioned the reference material as unscientific and critics claimed it was a mass indoctrination attempt by the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), which has linked the protection of cows — considered sacred in Hinduism — to its Hindu nationalist policies and rhetoric (Times of India, 22 February 2021). Since the BJP came to power in 2014, laws protecting cows have been amended in several states to include stricter punishments for cow slaughter. Right-wing Hindu nationalist organizations, such as the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), and other cow vigilantes have been emboldened to attack minority groups, including Christian, Muslim, Dalit (formerly known as “untouchables”), or Adivasi (Indigenous) communities, under the guise of protecting cattle. This report analyzes trends in political violence connected to nationalist rhetoric around cow protection in India.

Cow Vigilante Violence Trends

Laws preventing the slaughter of cows are not new in India and have been in place in some states since as early as 1932. However, recently, several states, including Gujarat, Uttar Pradesh, Karnataka, Haryana, Sikkim, and Madhya Pradesh, have made amendments to these laws (Human Rights Watch, 2019). These amendments include stricter punishments for cow slaughter and in some cases also criminalize the transportation, possession, and/or sale of cattle and/or beef (Human Rights Watch, 2019).

The RKA, which was set up in February 2019, aims to address several issues related to the conservation and protection of cows. The establishment of the RKA was one of the many measures undertaken by the BJP government to fulfill the promises made in their 2014 election manifesto to protect cows.

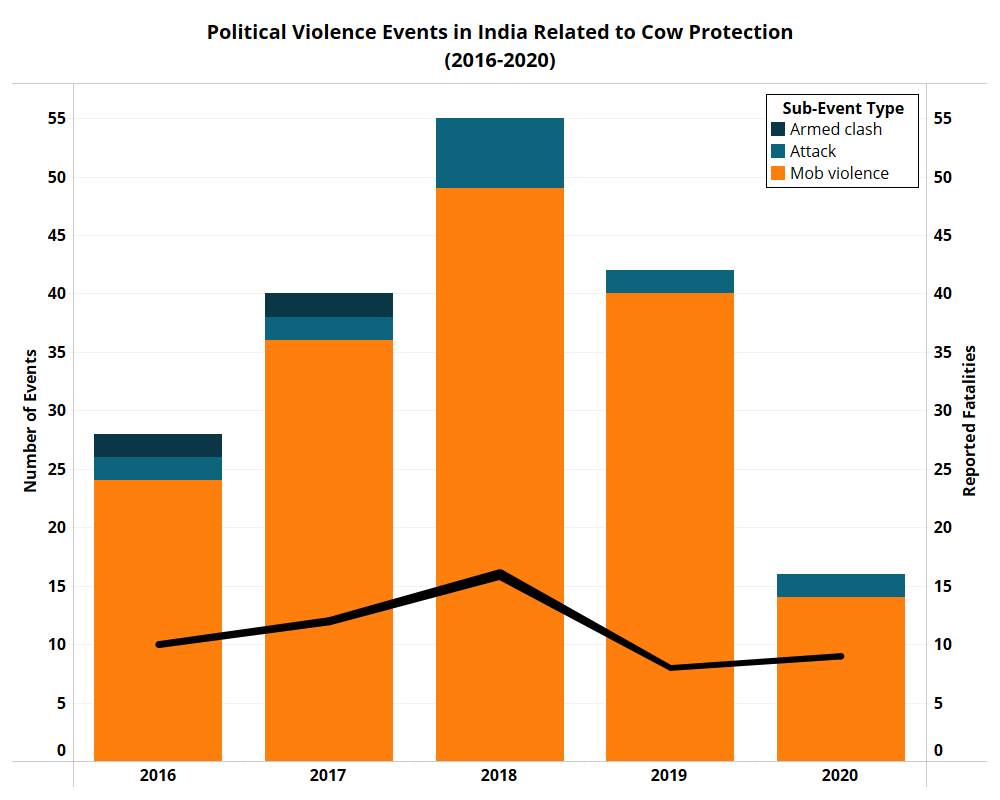

The introduction of legislation and adoption of stricter laws has coincided with a rise in violence related to cow protection across the country. From 2016 until the end of 2020, over 50 fatalities have been reported as a result of lynching or mob violence following suspected cow slaughter or trade. ACLED records a sharp rise in the number of incidents of political violence related to the protection of cows in India in 2018. Compared to 2016, political violence events related to cow protection increased by over 40% in 2017 and nearly doubled in 2018. These increases in violence have also coincided with the ascension of right-wing Hindu nationalist BJP-led governments in several states, including Uttar Pradesh, Assam, and Jharkhand (Quint, 4 December 2018; Hindustan Times, 16 July 2017).

In 2020, the number of events decreased by more than half compared to 2019. Months of stringent lockdown measures aimed at curbing the spread of the coronavirus are a likely reason for this sharp decline. Despite the lockdown, 16 political violence events were recorded in 2020 resulting in nine reported fatalities (see figure below).

Violence Against Civilians

Violence Against Civilians

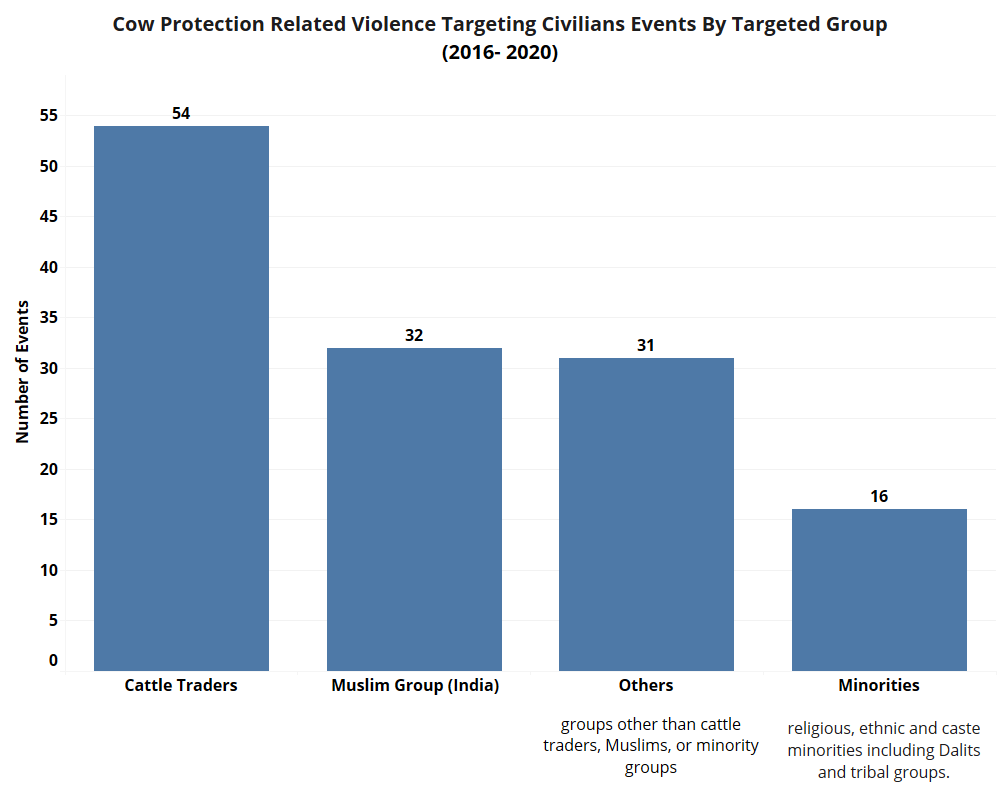

Over 80% of the reported events of violence related to protection of cows have been directed towards civilians. The victims of these attacks are usually those working in the cattle trade and people belonging to minority groups, including Muslims, Dalits, or Adivasi communities. The rise in stringent laws across the country has enabled the targeting of minority groups — many of whom are already particularly vulnerable to targeted violence — in the name of cow protection. Muslims and Hindus belonging to lower castes (Dalits) have often been the subject of hate speech, threats, and attacks since the BJP government came to power (Minority Rights Group International, 2017). These minority groups have traditionally relied on the leather, beef, and cattle industry for their livelihood, with Dalits taking on what was considered to be the lower-caste roles of disposing and skinning cow carcasses, while Muslims have traditionally run slaughterhouses and meat shops. Both Muslims and Dalits have worked in the leather and beef industry by carting cattle and as laborers in tanneries.

These groups espouse Hindutva, the philosophy that India ought to be a Hindu homeland. In 2014, and again in 2019, the BJP, under the leadership of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, was elected to power after advocating for social policies that include elements of Hindutva. Modi is himself a member of the RSS and was once a full-time RSS worker. RSS, as well as its organizational offshoots, all aim to promote an idea of a Hindu religious nation through Hindutva (Padmaja Nair, 2009).

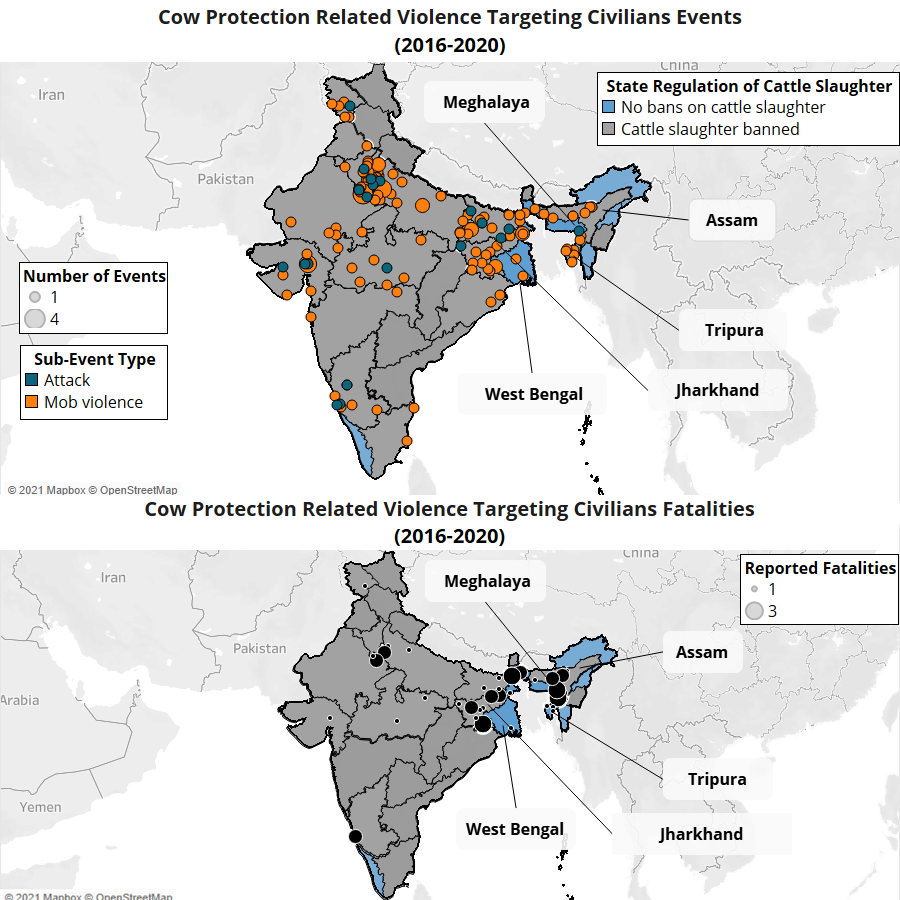

In 20 out of the 28 states in India, the slaughter of cows and calves is prohibited, and it is a cognizable offense whereby the police can make an arrest without a warrant (Harvard Politics, 4 February 2020).1In several states, cows and other cattle beyond an age are considered ready for slaughter after a ‘Fit For Slaughter’ certificate is provided by a veterinary expert (Department of Animal Husbandry and Dairying, Government of India; Factly, 1 January 2021; Hindu, 8 February 2021). The majority of the violent incidents — 92% — recorded by ACLED have taken place in states where cattle slaughter is banned, indicating that states with stringent legislation on cow slaughter are prone to cow vigilante violence (see map below). From 2016 to 2020, the highest number of fatalities from such vigilante violence was reported in Assam, while during the same period, Jharkhand reported the second highest number of fatalities. Cow slaughter is banned in both states.

The remaining violent events occurred in Meghalaya, West Bengal, and Tripura, where currently there are no bans on cow slaughter. Yet, these three states border Bangladesh where cattle theft is frequent. Estimates from India’s Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) show that tens of thousands of cattle are smuggled into Bangladesh from India every year (Indian Express, 7 January 2021). Nearly 25% of the total fatalities from cow protection-related violence have been recorded in these three states. Three events recorded in mid-2017 and mid-2018 were particularly lethal, with mobs of villagers lynching alleged cattle lifters, following reported incidents of cattle theft in the area. Such incidents of mobs and vigilante cow protection groups assaulting locals suspected of cow theft have become common in these states.

Lack of Response from State Actors

In July 2016, following a string of assaults on members of the Dalit community by right-wing Hindu nationalist groups over the alleged slaughtering of a cow, an unprecedented surge of demonstrations was recorded across the country and particularly in the state of Gujarat (for more on the 2016 Dalit protests, see this ACLED report). The demonstrations led to the resignation of then Chief Minister of Gujarat, Anandiben Patel. Prime Minister Modi denounced mob lynching in the name of cow protection to appease the demonstrators (Reuters, 1 August 2016).

In 2017, Manav Suraksha Kanoon or The Protection From Lynching Act (MASUKA) was drafted. The MASUKA proposed denying bail for those accused of mob lynching, as well as life imprisonment for those convicted. However, the MASUKA has yet to be passed by the Indian government. In July 2018, the Supreme Court of India set out clear directives to the Centre and several states to deal with lynching and mob violence while delivering a judgement in a writ petition filed by activists from the National Campaign Against Mob Lynching (First Post, 26 April 2020). Following the directives, as of 2020, only three states — Manipur, West Bengal, and Rajasthan — have enacted laws against mob lynching.

There has also been widespread opposition to the increased power being given to security forces in the name of cow protection. In cases where violation of cow protection legislation is suspected, not only can the police arrest suspects without a warrant, but they also have the permission to enter, stop, and search premises, as well as to seize animals to ensure that they are not being treated with cruelty. In October 2020, the Allahabad High Court found that the Uttar Pradesh Cow Slaughter Act of 1955 was being “frequently misused” by the authorities to target innocent persons in the state (Scroll, 26 October 2020).

A Brief Pause in Violence Followed By New Legislation

The onset of the coronavirus pandemic and related lockdown restrictions in 2020 likely contributed to the sudden decrease in the number violent incidents related to cow protection. Beginning in June, several states began to gradually reopen. Ten out of 16 events and eight out of nine reported fatalities in 2020 linked to violence stemming from cow protection were recorded in the second half of the year, from July to December. Since the beginning of 2021, three violent incidents related to cow protection have been reported in Karnataka, Tripura, and Bihar. One fatality was reported in the incident in Bihar, and members of the Muslim community were reported to be the victims of the incident in Karnataka.

After the reopening of the country, the BJP and other right-wing organizations, including the RSS, VHP, and Bajrang Dal, continued to push for more cow protection legislation. In October 2020, a “cow cabinet” — consisting of members from six departments of the state government working for the conservation and welfare of cows — was established in Madhya Pradesh (The Hindu, 18 November 2020). In Karnataka, the state’s legislative assembly passed the Prevention of Slaughter and Preservation of Cattle Bill in December 2020. The bill passed despite opposition from Dalit rights organizations, farmer groups, and butcher communities over the impact of the bill on both individual freedom and their livelihoods (The Wire, 7 December 2020). Later in December, the state’s BJP government implemented a bill banning cow slaughter by issuing an ordinance (The Hindu, 28 December 2020). The BJP leads the incumbent state governments in both Madhya Pradesh and Karnataka.

On 18 January 2021, the Prevention of Slaughter and Preservation of Cattle law came into effect in Karnataka. Following the enactment of the law, the Karnataka Minister for Animal Husbandry stated that cases registered against “cow vigilantes” would be withdrawn (New Indian Express, 20 January 2021). Under this new law, those who commit violence in the name of cow protection could be deemed to be people acting in “good faith,” raising concerns about impunity over vigilante violence (Wire, 10 February 2021). Similarly, in February 2021, the BJP central government proposed a law to impose a complete ban on the slaughter of cows and the sale, storage or transportation of beef or beef products in any form. The maximum punishment for breaking the law would be life imprisonment in the Union Territory of Lakshadweep (Bar and Bench, 26 February 2021). Over 96% of the Union Territory of Lakshadweep’s population is Muslim, and the community will likely be impacted by the proposed law due to their involvement in the cattle trade and consumption of beef (Government of India, 31 March 2011).

These actions signify the BJP government’s intention to push for more cow protection legislation and stricter punishment across states. Without concrete legislation to curb vigilante violence, this push will likely embolden vigilantes and create an environment enabling increased vigilante attacks in the name of cow protection. The resulting violence is likely to be disproportionately enacted against civilian minority groups, including Muslims and Dalits.

Violence Against Civilians

Violence Against Civilians