Most religious holidays and festivals carry a potential for state repression and minority contestation. This is explained by three main factors: firstly, celebrations serve as a focal point in heightening identity salience; secondly, during major festivals, worshipers tend to defy state orders; thirdly, religious celebrations and rituals can disguise political claims and work as sites of minority contestation and resistance (Hintz & Quatrini, 2020; Scott, 1992). All these general assumptions apply to the Islamic holy month of Ramadan. During Ramadan, Muslims aim to “be pious, moral, and disciplined” (Schielke, 2009). However, a heightened emphasis on religious practice also tends to fuel sectarian cleavages and state repression.

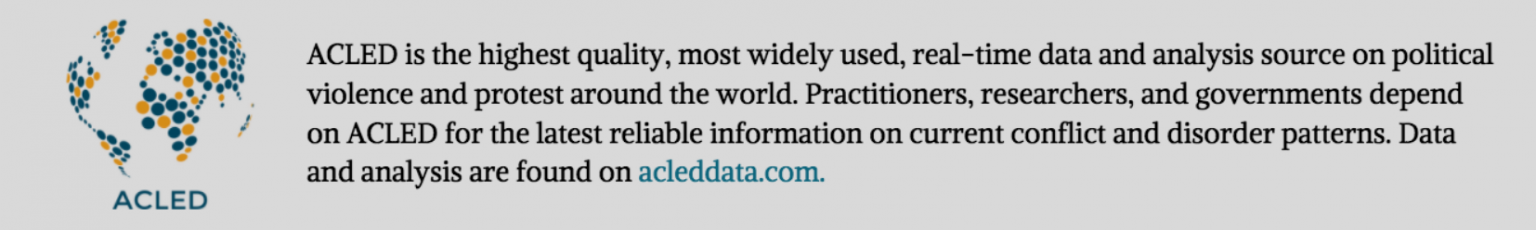

In comparison to previous months of 2021, ACLED-Religion data show an overall increase of repression events focused on Muslim religious practices during Ramadan, which ran from 12 April to 12 May (see figure below). This upward trend is underpinned by a large number of repression events specifically targeting Ramadan-related religious practices1Ramadan-related religious practice is determined based on an explicit reference to the suppression of Ramadan rites (e.g. tarawih, iftar, etc.) or to the enforcement of norms and regulations specifically decreed for the month of Ramadan. The estimate is conservative, since sources may not explicitly mention the connection between a given repression event and Ramadan-related religious practice. in five countries: Yemen, Bahrain, Iraq, Palestine, and Egypt.2ACLED-Religion did not record significant spikes in religious repression events targeting Ramadan-related practices in Iran or Israel. Overall, Ramadan-related repression accounts for 60% of all repression events targeting religious practices during the Islamic holy month.3ACLED-Religion currently covers seven countries in total: Bahrain, Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Palestine, and Yemen. The trend can be ascribed to four main drivers: state suppression of Ramadan-related rituals for sectarian reasons; enforcement of COVID-19 restrictions; interaction of Islamic and non-Islamic celebrations; and politicization of religious practice.

The form and legitimacy of Ramadan rituals are interpreted differently within each Islamic school (madhhab), and are subject to political considerations. Tarawih prayers exemplify this contested dimension. The tarawih is an optional prayer performed after the final daily prayer, which many Muslims believe will yield divine rewards if performed during Ramadan (Gulf News, 13 April 2021). Tarawih consists of 20 repetitions of ritual movements and supplications (raka‘a) interspersed with a ‘pause’ every four raka‘a (Wensinck, 2012). It is performed in the first part of the night, shortly after the evening prayer (‘isha), and it can last for several hours. Tarawih prayers pose a logistical challenge to state enforcement of COVID-19 restrictions because they foster large gatherings of people for several hours. In addition, tarawih is also subject to contrasting religious interpretations. ACLED-Religion captures 46 repression events related to the suppression of tarawih across five countries. Of these events, more than 70% are recorded in Houthi-controlled Yemen, where repression is grounded on purely sectarian reasons.

Yemen

In Yemen, tarawih is mainly practiced by Sunni Muslims. Tensions surrounding it date back to the 1990s and were fuelled by the rivalry between Zaydi revivalists and Salafists (Al Bayan, 23 August 2020; Weir, September 1997). Since at least 2014, the Houthis have hindered this religious rite in the capital Sanaa and other areas under their control (Ad Dali News, 17 July 2014; Irfaa Sawtak, 1 June 2018). Multiple Houthi religious and political authorities have recently issued statements that tarawih prayer should be performed privately, at home.4Including Mufti Shams Al Din Sharaf Al Din, Zaydi scholar Abdullah Al Daylami, and member of the Supreme Political Council Muhammad Ali Al Houthi (YouTube, 26 April 2021; Yemen Scholars, 2018; Twitter, 1 May 2021). In line with other fatwas — including the one issued by Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani in Iraq (Theological Research Center, 2010) — Houthi authorities interpret collective tarawih prayers in the mosque as an innovation (bid‘a) introduced by the second Caliph Umar Bin Al Khattab.

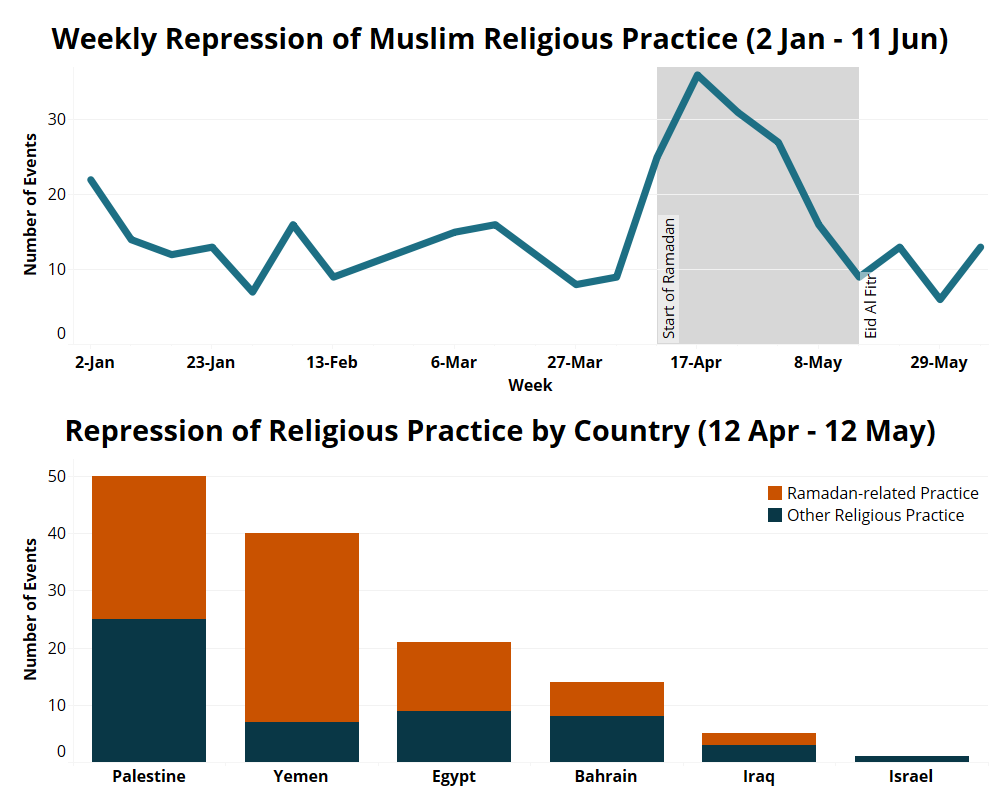

ACLED-Religion shows an uptick of religious practice repression perpetrated by pro-Houthi forces during Ramadan (see figure below). Most repression events are concentrated around the capital Sanaa (see map below), targeting — in addition to tarawih — other Ramadan-related rites (e.g. iftar, tahajjud, and i‘tikaf5Iftar is the act of breaking the fast immediately after the sunset call for prayer (maghrib). The tahajjud is a prayer taking place in the second part of the night. I‘tikaf is a religious retreat usually performed in mosques during the last 10 days of Ramadan (Plessner, 2012).) due to sectarian reasons. Of particular concern is the escalation of repression of women events perpetrated by the Zainabiyyat, a pro-Houthi female ‘moral’ police force (UNPoE, 5 May 2020). ACLED-Religion records 19 events specifically targeting women’s religious practice and aimed at imposing Houthi ideology.

Egypt

Unlike Yemen — where Houthi authorities did not announce any COVID-19 restrictions — Egypt preemptively introduced specific COVID-19 measures in anticipation of the month of Ramadan. In late February 2021, the Egyptian government announced a series of measures particularly aimed at preventing the spread of COVID-19 in mosques during Ramadan, including limitations on the number of attendees in mosques and the shutdown of shrines (Al Masry Al Youm, 27 February 2021). Between March and May, it strengthened these restrictions, placing limitations on a number of Islamic practices: iftar, tahajjud, and tarawih prayers; Friday sermons; Eid celebrations; and visits to cemeteries (Al Masry Al Youm, 30 March 2021; El Fagr Online, 3 May 2021; Egypt Independent, 11 May 2021; Al Masry Al Youm, 12 May 2021).

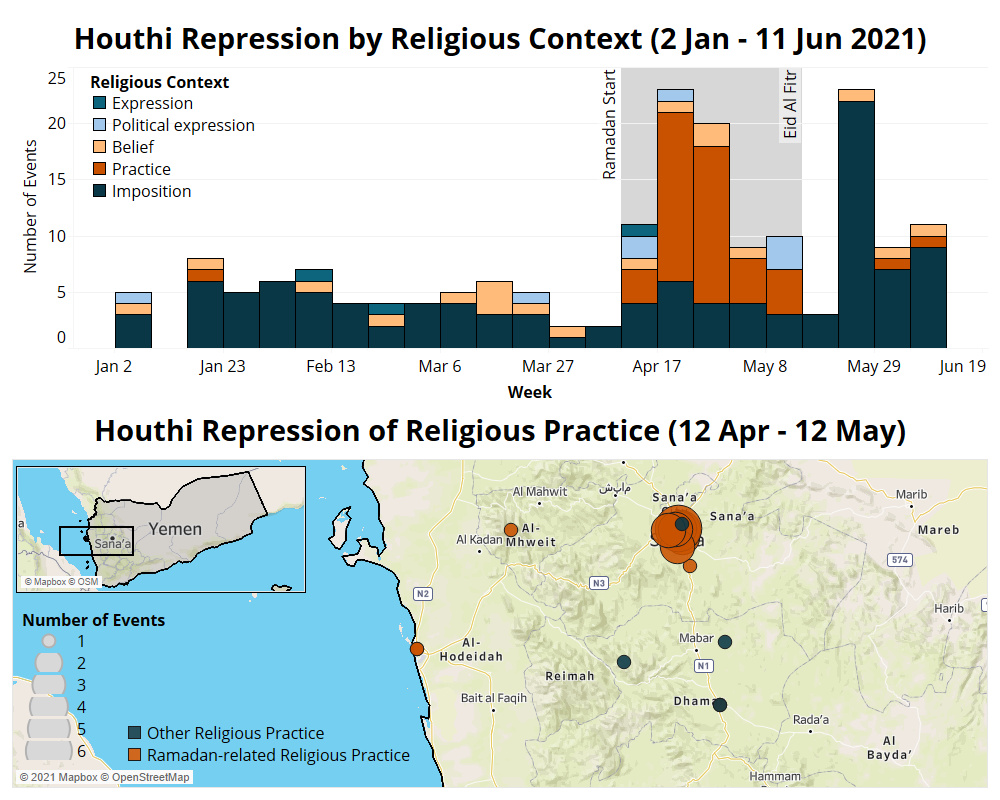

ACLED-Religion captures the enforcement of these restrictions between 12 April and 16 May in the form of 13 prevention of practice events targeting mosques that defied COVID-19 restrictions and six other harassment events targeting imams who did not abide by the preventive measures. In addition, ACLED-Religion records an uptick in the number of repression of religious practice events coinciding with the Eid Al Fitr holidays (see figure below), between 12 and 16 May (France 24, 5 May 2021). This spike coincides with the Islamic ‘summer wedding season,’6Repression events targeting weddings in the aftermath of the Eid are coded with ‘unknown’ as the victims’ religious affiliation. Although it is plausible to assume that victims are Muslim believers, most sources did not specify any religious affiliation for this type of events. propelled by the holidays and the return of expatriates (Independent Arabia, 12 June 2020).

As a term of comparison, it is interesting to observe how the Orthodox Christian Easter holiday, celebrated on 2 May, was handled in the same country. By the end of January, the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria announced the resumption of daily mass services with limited capacity and with only one person allowed per bench (Al Masry Al Youm, 26 January 2021). ACLED-Religion records 45 repression events targeting the Orthodox Coptic Christian community during the Ramadan period (see figure above). In all cases, the suppression of Orthodox rites was self-enforced by local archbishops, with no intervention from state authorities — a major difference in comparison with the repression of Islamic practice. An uptick in repression events targeting Coptic Orthodox Churches is visible on 17 April 2021, when the Church of Alexandria extended restrictive measures in view of the upcoming Easter holiday (Al Masry Al Youm, 17 April 2021).

Bahrain

Unlike in Egypt, Bahraini authorities eased COVID-19 restrictions in the lead up to Ramadan. The government announced the reopening of Shiite congregation halls (matams) and mosques, though authorities limited in-person ritual attendance to vaccinated male adults (Bahrain Mirror, 8 April 2021; Gulf News, 9 April 2021). Despite the lifting of restrictions, ACLED-Religion records one judicial harassment event, one threat event, and nine prevention of practice events in Bahrain during Ramadan. Of particular concern is the denial of iftar meals in Jaw Prison, recorded on 27 April. Notably, celebrations of Laylat Al Qadr were regulated by an ad hoc decree, issued on 2 May, which restricted the capacity of mosques and limited attendance to men who had received the second dose of the coronavirus vaccine (Gulf Daily News, 3 May 2021).

Iraq

In Iraq, Ramadan was preceded by a heated debate on the closure of places of worship due to a second wave of COVID-19 infections in the country. On 13 February 2021, the federal Iraqi government announced restrictive measures including the shutdown of mosques and husayniyyas (Shiite congregation halls) (Rudaw, 13 February 2021). The decision was implemented by both the Shiite and Sunni Endowment Offices and supported by prominent Shiite clerics, including Muqtada Al Sadr, who announced the suspension of Friday prayers across the country (Nina News, 14 February 2021). However, prominent Sunni scholar associations — including the Iraqi Jurisprudential Congregation — vocally opposed the measures (Iraqi Jurisprudential Congregation, 11 March 2021).

On 17 March, in overt defiance of the government directive, the Union of Imams in Baghdad announced the reopening of mosques (Twitter, 17 March 2021). Two days later, to avoid overt confrontation, the Higher Committee for Health and National Safety of the Iraqi government announced the reopening of mosques across the country (Waid Iraq, 19 March 2021). Against this backdrop, the Iraqi federal government did not decree any restrictions on religious practice during Ramadan. Accordingly, ACLED-Religion does not capture any repression events focused on Ramadan-related rituals in the areas controlled by the federal government. On the other hand, despite reopening mosques in the Kurdistan region, the Kurdistan Regional Government maintained limitations on religious practice, including the sustained closure of women’s halls (Kurdistan 24, 11 April 2021). Additionally, it decreed a three-day lockdown across the region over the Islamic Eid Al Fitr holidays (Shafaq, 30 April 2021). ACLED-Religion does not record any direct enforcement of these restrictive measures.

Palestine

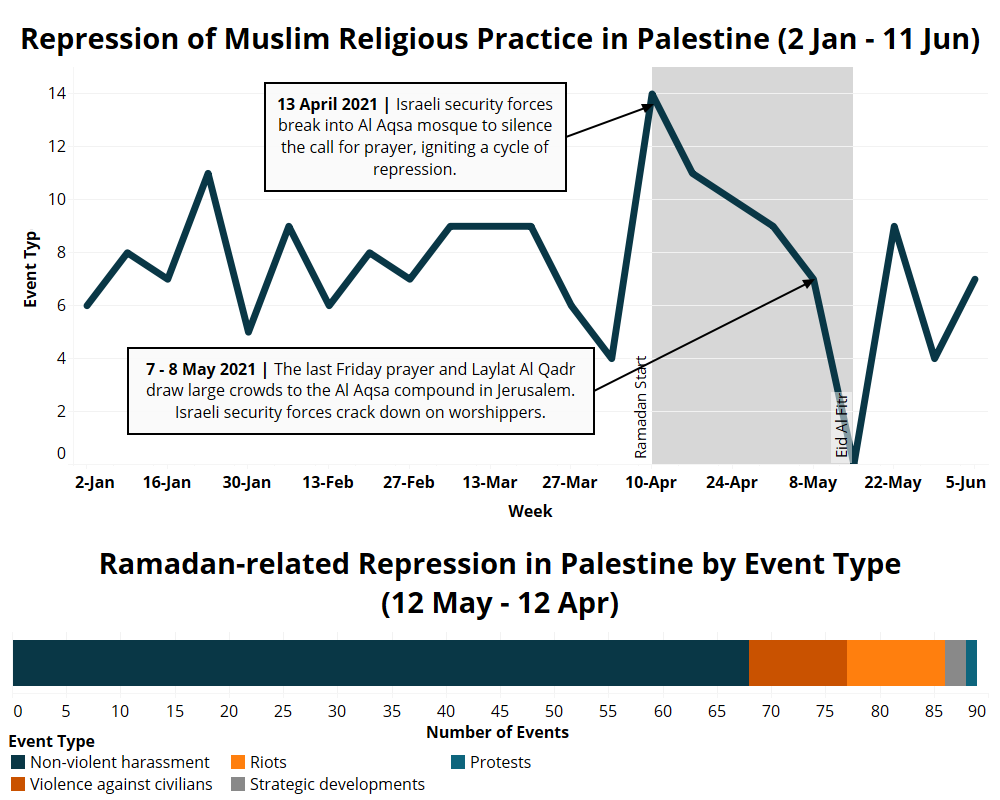

In Palestine, the number of repression events focused on religious practice and involving Muslim worshipers decisively trended upward during Ramadan (see figure below). Repression mostly revolved around the Al Aqsa complex in Jerusalem’s Old City, a holy site for both Muslims and Jews. Notably, an initial uptick in the number of repression events coincided with Yom Hazikaron, the Israeli commemoration for the Fallen Soldiers of Israel and Victims of Terrorism, celebrated on 13 April (Chialà, 2013). During the commemoration, newly inducted Israeli soldiers prayed at the Western Wall in Jerusalem, while the Muslim evening call to prayer (adhan) simultaneously resonated from Al Aqsa. Israeli security forces attempted to silence the adhan. They broke into the Al Aqsa Mosque and cut the electric cabling to loudspeakers in four minarets (RNS, 16 April 2021).

This violation of the Al Aqsa compound ignited a cycle of violence. Israeli police forces, under the pretext of enforcing COVID-19 measures, engaged in systematic and almost daily repression of Ramadan rituals, suppressing tarawih prayers and i‘tikaf; forbidding the introduction of food in Al Aqsa; and disbanding ‘after-prayer’ gatherings within the compound. On the first Friday prayer of Ramadan — a recurrence strictly observed by Muslim believers (Schmitt, 2019) — police also limited access to Al Aqsa to only 10,000 Palestinians from the West Bank (Al Quds City, 16 April 2021). ACLED-Religion data show that the repression of Ramadan-related rituals was combined, in at least nine cases, with ensuing riot events (see figure above). The suppression of religious practice also led members of Palestinian civil society to politicize tarawih prayers as a form of protest against Israeli police attacks targeting Muslim worshipers (Al Quds City, 24 April 2021).

As widely reported by international news outlets, tensions around the eviction of Palestinian residents in Jerusalem’s Sheikh Jarrah neighborhood escalated into overt conflict between Hamas and Israel on 10 May (for more on the conflict, see this ACLED Regional Overview). Simultaneously, Israeli forces carried out acts of religious practice repression at Al Aqsa in response to two Ramadan-related events: the last Friday prayer (7 May) and Laylat Al Qadr (8 May).

In the lead up to these events, Israeli police forces set up checkpoints to limit access to the Old City of Jerusalem (Al Ittihad, 30 April 2021; Al Watan Voice, 7 May 2021). Meanwhile, the Islamic Movement called on Palestinians to increase their presence in Al Aqsa to repel Israeli settlers (Al Watan, 6 May 2021). The last Friday prayer drew more than 70,000 worshipers to Al Aqsa who later joined a demonstration in solidarity with the Palestinians evicted in Sheikh Jarrah (Middle East Eye, 12 May 2021) — a clear example of how religious celebrations can be turned into a site of minority contestation (Hintz & Quatrini, 2020). The following day, on Laylat Al Qadr, more than 90,000 worshipers gathered in Al Aqsa (Times of Israel, 8 May 2021). Israeli forces attempted to disperse the worshipers and evacuate the compound. Similar repression events occurred on 9 May.

ACLED-Religion records an uptick in repression events focused on Muslim practice across the 7-9 May period. Another relevant incident is recorded on 10 May due to the occurence of the Israeli Jerusalem Day — or Yom Yerushalayim, a minor religious celebration meant to commemorate the reunification of Jerusalem. On this occasion, the Israeli police cracked down on Palestinian worshipers in Al Aqsa Mosque as they were setting off to demonstrate against Yom Yerushalayim (Middle East Eye, 12 May 2021).

Conclusion

In conclusion, an escalation of Muslim practice repression was recorded in five of the seven countries covered by ACLED-Religion during Ramadan 2021. In Yemen, the repression of tarawih prayers amplified pre-existing sectarian divisions, deepening the identitarian cleavage between Zaydi and Sunni believers. In all other countries, COVID-19 restrictions played a major role in limiting religious practice. However, related repression patterns were far from homogeneous. In Egypt and Bahrain, state authorities systematically suppressed any attempts at defying COVID-19 restrictions. In Iraq, on the other hand, the federal government opted for a more cautious approach: it avoided enforcing restrictions, rather than risk fueling sectarian cleavages. Eventually, in Palestine, multiple factors contributed to the ignition of a cycle of violence: the enforcement of COVID-19 restrictions; the co-occurrence of Jewish and Islamic religious celebrations; and the politicization of religious practice.

Funding for this report was provided by the US Department of State’s Bureau of Conflict and Stabilization Operations through the Quantifying Religious Repression and Religious Conflict grant. The views expressed in this report are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the United States Government.