This is the first of two analysis features examining recent developments in South Sudan. The country has been experiencing a surge in ‘communal’ violence in the wake of a peace agreement signed in 2018, as the oil economy that has underpinned South Sudanese elite politics for over 15 years begins to disintegrate. This first analysis — Surface Tension — re-interprets ‘communal’ violence in South Sudan, situating conflicts organized around ethnic or sub-ethnic lines in relation to national-level conflicts and inter-elite rivalries. These conflicts and elite dynamics are changing in response to the decarbonization of South Sudan, which is pushing elite ambitions away from the capital and back into provincial areas. The (forthcoming) second analysis — Decarbonizing South Sudan — explores this theme in greater detail through reevaluating the relationship between oil and conflict in South Sudan. This involves investigating the distinctions and overlaps between ‘carbonized,’ ‘decarbonized,’ and ‘uncarbonized’ conflicts in the country, and highlighting the risks posed to an elite order dominated by military and security factions amid escalating public discontent.

ACLED’s previous report on South Sudan – Last Man Standing – engaged with the high-level politics of South Sudan in the wake of the 2018 peace agreement, the Revitalized Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in South Sudan (R-ARCSS). Another ACLED report, Red Lines, from earlier this year explored some of the international dimensions of the escalating violence and tensions in the Horn of Africa, including the awkward position South Sudan has been left in as a result of deteriorating relations between its more powerful neighbors of Sudan and Ethiopia. This series picks up from where Last Man Standing left off, exploring violence from late 2019 to present. This series focuses on two longer term problems afflicting South Sudan, which have come to the fore once again in the aftermath of R-ARCSS. The first of these is the resurgence of so-called ‘communal’ violence in the country, and the second is the approaching twilight for South Sudan’s oil sector which has guided South Sudan’s political trajectory and economic maldevelopment for almost two decades.

South Sudan has experienced increasing violence in the wake of R-ARCSS, most of which is not straightforwardly connected to the recent civil war (2013-2018). The states of Warrap, Lakes, and Jonglei in the central belt of the country have been the most severely affected, though violence has also been escalating in the Greater Equatoria region to the south and in Unity and Upper Nile states in the north. Much of this unrest has been cast as ‘communal’ and ‘inter-ethnic’ in nature by South Sudan’s elite, while targeted killings linked to these events continue to be attributed to seemingly ubiquitous ‘unknown gunmen.’ Although such violence is presented as being chaotic or random in nature, the frequency and intensity of these conflicts has tended to increase during times of increased competition and discordance among South Sudan’s elites. Over the past thirty years, these conflicts have evolved into a “mutant breed of traditional forms of raiding and extensions of political rivalries at the national level,” which have been violently (and selectively) regulated through ‘civilian disarmament’ campaigns (Wild et al., 2018: 2).

Each of these ‘communal’ conflicts are complex in their own right, and in some instances have a complicated relationship to the political developments among South Sudan’s contending elite factions. There is much unfinished business from the recent civil war, with enduring rivalries between and especially within the signatories to R-ARCSS. Peace agreements in South Sudan have typically reorganized power rather than changed the way it functions, and reflect the priorities of South Sudan’s military elites alongside the country’s neighbors and external partners while mostly ignoring those of its civilian population. In the case of R-ARCSS, the reorganization of power has been mostly cosmetic, with the rebel groups and (largely irrelevant) political parties who signed the agreements taking their place in a bloated power-sharing government. Within this enlarged government, actual power remains concentrated in the clique around the presidency and a few well-connected security and military elites.

This reorganization of power has nevertheless created grievances among commanders who feel threatened by changes their leaders are making, and who are in some cases troubled by the disregard shown towards the communities they represent by these same leaders. Military heavyweights within rebel groups who signed the agreement are increasingly discontented with the sluggish progress in implementing the provisions of R-ARCSS (International Crisis Group, 2021), particularly within the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement – In Opposition (SPLM-IO, or IO, the largest of South Sudan’s rebel groups). A long-brewing dispute between IO leader Dr. Riek Machar and his former Chief of Staff General Simon Gatwech Dual recently erupted into serious fighting in the Meganis area of Upper Nile state (New York Times, 9 August 2021). Meanwhile, a number of high-profile defections from the IO to the government has further strengthened the government’s dominance of the postwar order, with several commanders peeling away from Machar over the past two years after inducements from the government. These defections have been linked to violence involving both irregular militias and regular military forces in parts of Central Equatoria, Western Equatoria, and Upper Nile states.

As South Sudan’s conflicts expand, oil production has continued to contract. Since the 1970s, the Sudanese political and security establishment has attempted to bring the oil revenues of what is now South Sudan online, and eventually succeeded in doing so in the late 1990s after displacing the population residing in the Southern oil fields (Patey, 2014). The influx of oil wealth ushered in a series of important changes within Sudan, while turbo-charging the state-building process in South Sudan since 2005 (de Waal, 2015: Chs. 5 and 6). Now the elites of South Sudan are grappling with the early stages of an involuntary or forced decarbonization of the country’s oil-dominated economy, just as their counterparts in Sudan have been attempting to do since South Sudan gained independence in 2011 (Watson, 2020). South Sudan’s oil revenues facilitated the integration of various militias, paramilitary, and rebel groups during the run-up to South Sudanese independence in 2011, and had sustained a vast military and civil service payroll until a combination of declining oil prices, payment obligations to Khartoum, and diminishing production (linked to the civil war, as well the depletion of reserves) forced the government in Juba to economize (de Waal, 2014; Thomas, 2019: 75; RVI, 2021: 25-28).

In the first section of this analysis, an overview of the central events that have led South Sudan to its current situation is given. Here some of the elements of the political system and its relationship to peace agreements and violence are also outlined, which challenge the view of South Sudan being the site of random violence stemming from an absence of state control. This section also suggests attempts at treating conflict as being chiefly ethnic or ‘communal’ should be treated with caution, and notes some unusual properties of the politico-military system which allow the regime in Juba to survive amid pressures which would overwhelm many other comparable states. The section highlights how much of the violence in South Sudan has little or no bearing on the stability of state and military structures in the country, with some violence even strengthening the position of the government.

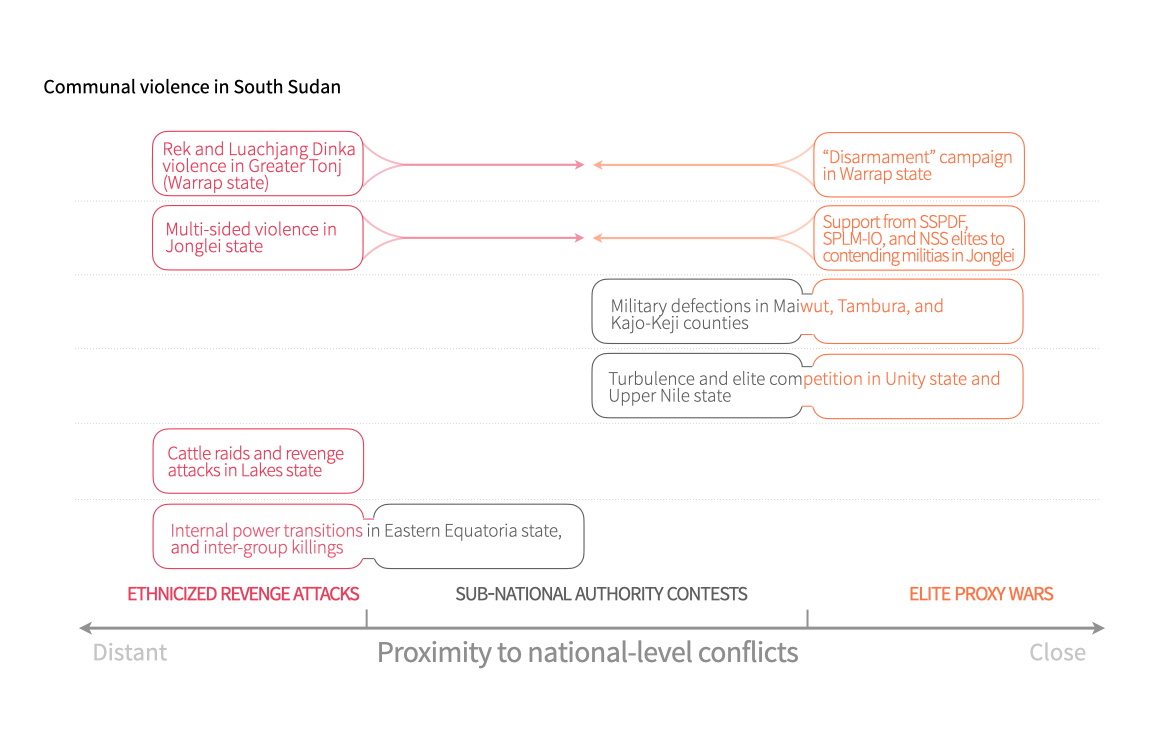

The following section of the analysis argues that a reassessment of ‘communal’ conflict is needed to more accurately understand the relationship between such violence and the overarching political and military structures of South Sudan. The language of ‘communal’ violence has obscured more than it reveals, and identifying the different strands of violence subsumed within it helps explain the connections and points of departure between this violence and national-level schisms and elite activity. Three subcategories are identified: ethnicized revenge attacks, subnational authority contests, and elite proxy wars. These forms of violence have distinct dynamics, with some being closely entwined with South Sudan’s political and military factions, and others being more distant from these factions, and/or closer to social forces and structures which have not been captured by the state. These subcategories are explored in relation to recent episodes of conflicts and disorder from across South Sudan, through case studies on violence in Lakes, Western Equatoria, Warrap, and Jonglei states.

The final section of the analysis considers whether the rise in subnational conflicts may be linked to changes in South Sudan’s political economy, and specifically the decarbonization of the country that is now underway. Amid the complex and sometimes idiosyncratic conflict dynamics, an overall direction is discernible which indicates that elite power is being (often violently) transferred away from Juba and into the peripheries. This represents a reversal of sorts from most elite trajectories prior to the recent civil war, in which elites sought to access the oil wealth and power concentrated in the capital. In sum, many elites have revised their ambitions downwards, and appear to be concentrating their activities in their home areas.

Underpinning this process is an imperative for South Sudanese elites to seek alternative sources of wealth (and thus power) as oil revenues continue to decline. Declining oil revenues have left growing numbers of military elites competing for similar numbers of senior positions in state and military bureaucracies, with these institutions no longer being in a position to financially sustain all of these elites. This process is facilitated by the contraction of the state around fewer parts of the country, as the regime seems increasingly disinterested in governing hostile rural areas of limited strategic or economic importance. This may result in long-term consequences for the geographical distribution of power in South Sudan, and accelerate changes in relations between provincial capitals and Juba. In the shorter-term, there is every indication that this will result in continued subnational violence, which will likely cluster around sites of elite competition over access to non-oil wealth (in the form of land, commerce and cross-border trade, and more easily extractable natural resources) and to areas where elites can be expected to cling on to decaying sources of oil wealth.

Ten Years After: South Sudan Since Independence

South Sudan’s journey to eventual independence from Sudan in July 2011 is a complex and tragic one, which increasingly pitted Southern Sudanese elites and militias against one another to the detriment of the population at large.1A comprehensive account can be found in Douglas Johnson’s The Root Causes of Sudan’s Civil Wars (2003/2016) while Peter Martell’s First Raise A Flag (2018) is a particularly engaging entry point. Eddie Thomas’ South Sudan: A Slow Liberation (2015) provides an insightful and original treatment of South Sudan’s colonial history, charting the reproduction of the warped political economy bequeathed by successive colonial rulers and its reverberations in the present-day wars in the country. The First (1955-1972) and Second (1983-2005) Sudanese Civil Wars both shaped and violently reshaped the relations between Southern Sudanese societies, creating painful legacies among Southerners that live on in much of the violence and political resentment of today. In 2005, the rebel Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army (SPLM/A) was able to amplify its power by entering a sometimes tense power-sharing arrangement with the National Congress Party (NCP) government in Khartoum under the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA), paving the way for Southern Sudanese independence. The CPA-era saw numerous anti-SPLM/A rebel groups reach accommodations with the current President Salva Kiir (who is also head of the army and the SPLM), notably the large and fractious South Sudan Defence Forces (SSDF) paramilitary coalition, most of which integrated into the army after 2006.

The SSDF’s paramilitary forces were largely drawn from the Nuer ethnic group to the north and east of the country and several aggrieved Equatorian communities from the south, in contrast to the majority Dinka SPLM/A. Factional rivalries among Dinka from the Greater Bahr el Ghazal area to the north-west of South Sudan (generally associated with President Kiir) and those from the Greater Bor community east of the Nile (associated with former SPLM/A leader Dr. John Garang, who died in a helicopter crash in 2005) were resolved mainly in the favor of the Bahr el Ghazal Dinka, thanks in part to an alliance of convenience between President Kiir and the SSDF.

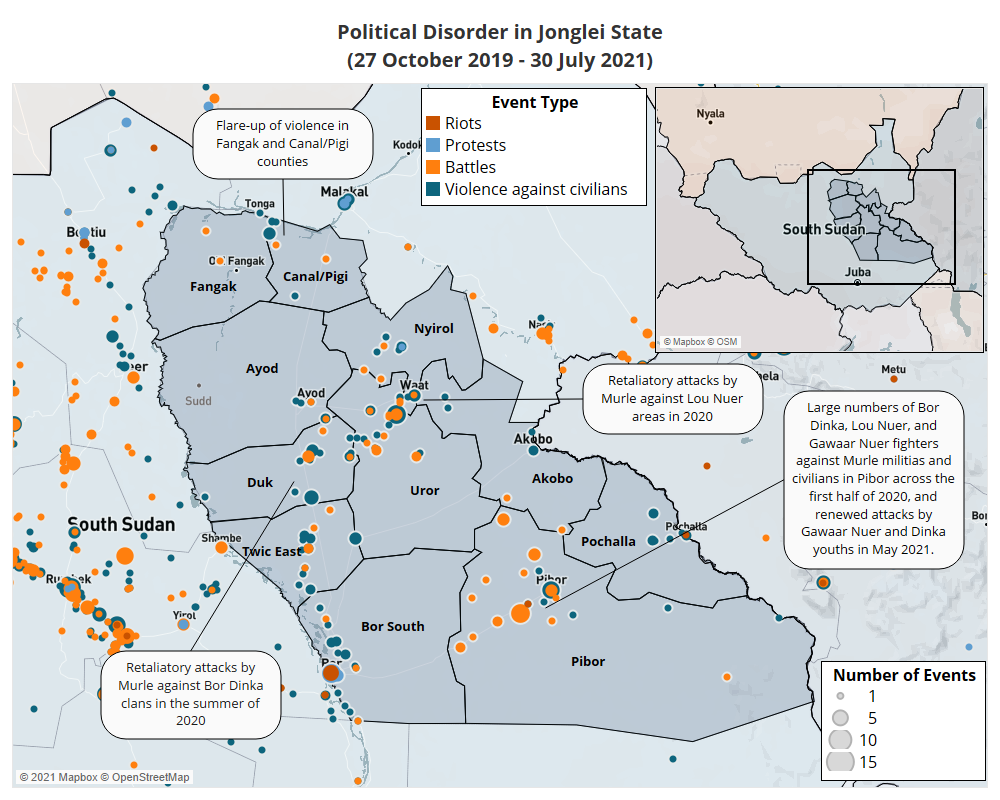

The accommodation between the SPLM/A government and the SSDF unraveled in mid-December 2013, when a paramilitary force raised by Paul Malong (who was at the time Governor of Northern Bahr el Ghazal state, and who was the army Chief of Staff from 2014-2017) from Dinka clans to the far north-west of the country engaged in massacres of ethnic Nuer civilians in Juba, amid in-fighting within the Presidential Guard (Young, 2015; see also The Elephant, 23 July 2021). Nuer ex-SSDF commanders and soldiers swiftly mutinied as violence spread across Juba and then to major towns and oil fields of the north-east, plunging the country into civil war. This war was at first concentrated in the three states of the Greater Upper Nile region (Jonglei, Unity, and Upper Nile) where South Sudan’s oil fields are located.

Dr. Riek Machar, the former Vice-President and one-time SSDF leader who had maneuvered himself into control of the SPLM-IO rebellion, signed a peace agreement with a reluctant government in 2015 (with the government motivated to sign the agreement under significant regional pressure and immense international pressure). This reluctance was shared by several IO commanders who harbored doubts about both Machar’s and President Kiir’s intentions. By this point, the government had greatly strengthened its control of the country (and of its own increasingly complex military system), thanks in part to the détente reached with Khartoum several months prior to the war, which saw South Sudanese NCP elites assume a more prominent role in the President Kiir’s government. Yet the peace agreement between the government and the SPLM-IO imploded in 2016, pushing the war from Nuer strongholds and the oil fields in the north-east into the Greater Equatoria region to the south and to Western Bahr el Ghazal state to the far west (Young, 2019).

The much-weakened SPLM-IO — whose original Nuer leaders were now forced to co-exist with new Fertit and Equatorian rebel factions from the west and south, and an autonomous Shilluk faction in Upper Nile state — signed R-ARCSS in September 2018, in a deal brokered by Uganda and Sudan. This brought the IO into an unwieldy power-sharing arrangement with the government and a raft of minor rebel groups and political parties. The government monopolized revenues and retained control of major towns and oil-producing areas, and was able to veto any particularly undesirable military and political nominations from the other signatories. Machar was physically isolated from more powerful commanders while under de facto house arrest in Juba, before politically isolating himself by appointing relatives to senior positions in the power-sharing government (Craze, 2020: 98-99). Meanwhile, counter-insurgency activities continued against the holdout National Salvation Front (NAS) rebel group in Central and Western Equatoria states, which saw the IO cooperating with government forces against NAS.2NAS was formed in early 2017 after senior commander Lieutenant General Thomas Cirillo (an ethnic Bari) resigned from the army. It has fought across much of Greater Equatoria, though intensive counter-insurgency operations have confined it to small parts of Central and Western Equatoria states near to the Congolese border.

Peace agreements in South Sudan give primacy to military factions and to the military elites who negotiate them, who can use these agreements to expand their political influence and share of economic resources at the expense of weaker or excluded groups. Military recruitment has typically increased after peace agreements are signed, while brutal ‘civilian disarmament’ campaigns are organized for truculent communities and holdout groups. These agreements are not associated with sustained efforts at demilitarizing South Sudan’s political culture or society at large, sections of which have been armed by belligerents during times of war. Peace agreements thus create conditions for dangerous struggles for power, wealth, and security among elites linked to factions in the security system, which can collude against rivals before turning on one another. In the shadow of peace time, irregular militias associated with these factions are often rearmed and remobilized, raising the risks of complex patterns of violence (including accumulation of economic assets) and score-settling dominating the peace time.

So far, South Sudan under R-ARCSS is heading straight down this path, only without the oil revenues needed to sustain a large military system which had been expanded at the height of the oil boom from 2005-2012. As will be argued later, this may have important implications for the direction of the current violence, since armed groups which might previously have sought to access oil rents and power in Juba (de Waal, 2014) may no longer be able to do so. Declining oil revenues may also undermine the attempts at appeasing elite groups through promotions and high salaries. The numbers of military commanders have reached new heights after the most recent war, with both the IO and government engaging in generous rounds of military promotions. Hundreds of IO officers were appointed as Brigadier or Major Generals, while on the government side, the 2019 budget showed there to be a remarkable 20 1st Lieutenant Generals; 103 Lieutenant Generals; 606 Major Generals; and 1,773 Brigadiers across the army, police, and National Security Service (NSS) (GRSS, 2019: 15). It will not be possible for the government to financially support these numbers given declining oil revenues and an increasing reliance on securing opaque loans from commodity traders (Africa Confidential, 30 August 2019), yet any large-scale demotion of military officers will be contentious (International Crisis Group, 2021: f.n. 35).

Ethnicity, Power, and Conflict

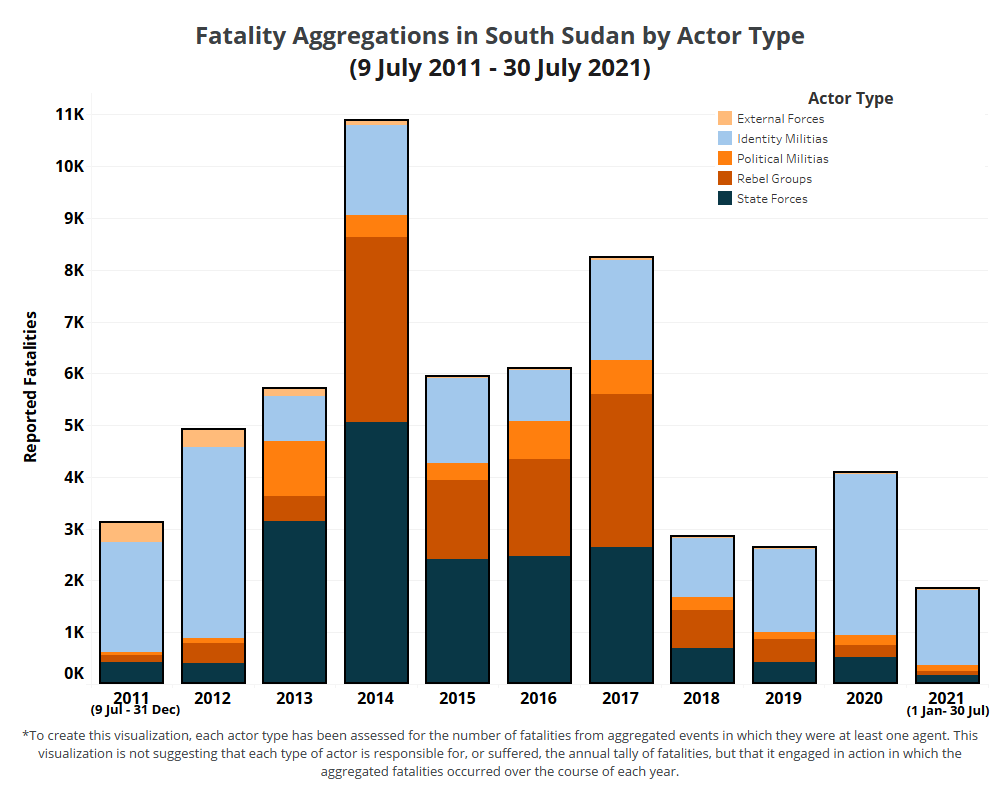

A recent United Nations report observed that: “While the signing of R-ARCSS has seen a reduction in hostilities at a national level for the second year in a row, vast swathes of South Sudan have seen a significant escalation in violence perpetrated by organized ethnic militias, on a scale that exceeds the manifestations of localized violence witnessed since the outbreak of the conflict in December 2013” (UNHRC, 2021: 18). On the surface, this troubling development is consistent with ACLED data, which show fatalities attributable to political and identity militias steadily climbing since 2018 (see figure below).3Note that fatalities for violence in 2020 are likely to underestimate the lethality of violence in Jonglei state, as the constraints on accessing several areas where violence has taken place has resulted in only limited information on the severity of the violence in such areas. In the event more reliable and comprehensive information emerges, this would likely increase the fatalities for the year by some margin. The principal actors involved in the increasing violence have been ethnic militias, with violence perpetrated by rebel and state security organs seemingly fading into the background.

When explaining the cause of this rising violence, the United Nations has often drawn attention to the delays in the appointment of state governors and commissioners, suggesting that conflict was the result of a breakdown of authority. This reasoning is exemplified in the following passage: “The power vacuum at the subnational level, a result of delays in the appointment of State governors, contributed to increased tensions and violent intercommunal clashes” (UNSC, 2020: 2).

Some caution is required when engaging with the notion that South Sudan is wracked by localized, ethnic conflicts that are brought into being whenever a power vacuum emerges. This reading of violence can encourage the view that there is some kind of deficiency in the South Sudanese state’s ability to extend its authority and institutional coverage, obscuring the ways in which so-called ‘inter-ethnic’ and ‘communal’ violence are instead a function of how the state deploys the authority it does possess. It also conceals the ways in which power vacuums are sometimes deliberately introduced or maintained by the government (Schomerus and de Vries, 2014), and conversely the ways in which a surge in the presence of state power can be linked to increased violence and abuses.

Further, and as the graph above shows, reported fatalities linked to ‘communal’ and ‘ethnic’ militias were significantly higher in 2012 (when governors and county commissioners were in place across the country) and noticeably lower during much of the 2013-2018 civil war (which was a time of administrative upheaval). This suggests any link being drawn between the onset of violence and vacancies of governors or commissioners is either incorrect, or else is only one part of the puzzle. It is possible that the UN draws connections between a lack of appointed officials and subnational violence because such officials constitute the main nodes with which the UN can interact, but it is equally possible that this is the result of an ingrained set of assumptions about the nature and causes of conflict which do not consistently align with reality.4Encouragingly, it should be noted that not all branches of the UN who engage with violence in South Sudan advocate this form of analysis. Reports from the UN Panel of Experts often diverge from the assumptions underpinning such analysis, while the UNHRC (2020: 5) observes how “the Commission has established that the attacks merely presented as cattle raiding are in fact highly politicised and systematically orchestrated, often involving organised armed militia groups under the command and control of the main parties to the conflict, including the South Sudan People’s Defence Forces (SSPDF) and members of armed opposition groups.”

An additional flaw with readings that emphasize the role of violent local actors flourishing in conditions of near anarchy is that it can give way to a particular understanding of violence in South Sudan as being something which is largely random in its regularity, cause, or conduct. While it is true that violence can emerge and escalate unexpectedly, it is more instructive to be conscious of how violence in South Sudan can be made to appear random, rather than actually being random in nature. This point will be returned to shortly.

War and sporadic violence in South Sudan have increasingly been approached through an ethnic lens, particularly since the 1990s where fighting among South Sudanese ethnic groups and clans markedly intensified following a series of damaging splits in the SPLM/A rebellion beginning in 1991. War has tended to reinforce ethnic identity markers and at times has made ethnic affiliation an organizing principle of violence. This was in part a result of the tendency of armed elites (both government and rebel) to tribalize conflicts as a military strategy and as basis for organizing campaigns, and in particular to encourage recruitment of co-ethnics by commanders (LeRiche, 2019).

South Sudan has a complex and unevenly researched ethnic landscape, typically understood to comprise at least 60 ethnic groups. Several of these groups — notably the largest ethnic groups, the Dinka and Nuer — are organized around elaborate lineage systems comprising a plethora of primary sections, sub-sections, and sub-sub-sections, while groups such as the Fertit to the northwest are in actuality a conglomeration of various smaller groups.5A useful overview of South Sudan’s ethnic groups can be found in South Sudan: A Shared Struggle (2013), which is the result of a collaboration between academics, archivists, and ethnographers, and was jointly published by the South Sudanese government and the UN Mission in South Sudan. Stephanie Beswick’s Sudan’s Blood Memory: The Legacy of War, Ethnicity, and Slavery in South Sudan (2004) provides an overview of the history of the different branches of the Dinka, with central and western Dinka clans (and the Atuot in eastern Lakes state, who are often incorrectly associated with the Dinka) being the subject of more recent in-depth research in the work of Naomi Pendle, Zoe Cormack, and the Rift Valley Institute. Sharon Hutchinson’s Nuer Dilemmas: Coping with Money, War, and the State (1996) and her subsequent work with several collaborators provide excellent accounts of parts of the Nuer ethnic group, while Simon Simonse’s Kings of Disaster: Dualism, Centralism and the Scapegoat King in Southeastern Sudan (1992 and 2017) engages with various aspects of Equatorian societies from the southeast of the country. These groups have distinctive relationships with a succession of violent colonial and postcolonial administrations, while some groups (such as the Atuot) have developed martial cultures in response to repeated raiding and/or encirclement from neighbors. During the course of several civil wars, ethnic groups have often come to be associated with particular factions and/or with government or opposition camps. Such associations tend to color the way these groups are treated by the belligerent who comes to dominate the peace in between these wars.

A specific consequence of the (sometimes imperfect) coupling of ethnicity and military command is that military commanders can feel beholden to act in the interests of their ethnic groups, and may be expected to come to the defense of their communities when they are under threat. This can put such commanders in a difficult position if the government or rebel group they belong to engages in violence against their own community. A number of prominent defections over the course of the most recent civil war were driven (at least in part) by community pressure in the face of abuses or atrocities committed by government forces, or by government decisions deemed to disadvantage their ethnic community (such as the replacement of the 10 states system with 28 and then 32 states in 2015 and 2017, which was partially reversed in 2020).6Prominent examples would include Lt. Gen. ‘CDR’ James Koang, Lt. Gen. Thomas Cirillo, and Johannes Okiech.

Conversely, ethnicity has often been mobilized for offensive (as opposed to defensive) purposes, or to disguise the true motivations of political and military elites. A number of contending factions and elements of the government in the First and especially Second Sudanese Civil Wars sought to exploit ethnic grievances and insecurities for ulterior purposes, with the effect that “propagating this version of community identity served as a means for conflicting elites to invoke legitimacy and influence, in lieu of providing more tangible public resources” (McCrone et al., 2021: 6).

This instrumentalization of identity extends to efforts at explaining these conflicts, and can take an important role in shaping supposed solutions to them. Outsiders have often accepted this questionable presentation of conflicts as being primarily ‘ethnic’ and ‘communal’ in character, and have accordingly proposed forms of local peacebuilding that address conflicts on this basis. There are inherent risks to doing so, not least of all because of the tendency of elites to write themselves out of these ‘communal’ conflicts, and for the structural features of South Sudan’s intensely militarized political economy to be dissociated from ‘communal’ violence. The belief that conflicts are fundamentally ethnic in nature has also be upscaled to the national-level conflicts in the country such as the most recent civil war, which in cruder accounts has been represented as Dinka-Nuer civil war between the ethnic ambassadors of the two groups, President Kiir (a Rek Dinka) and Dr. Riek Machar (a Dok Nuer). Whilst ethnicity permeates the recent civil war, it does so unevenly and in sometimes counterintuitive ways. Arguably, it is more often a byproduct of elite struggles to carve out control over the military and economic spheres than a straightforward cause of war.

Characteristics of Violence and Power in South Sudan

In order to make sense of contemporary violence in the country, it is important to outline three important aspects in the relationship between the state and organized violence in South Sudan. These are, firstly, the fundamentally military character of the state; secondly, the different types of violence which affect (or do not affect) the durability of this structure; and lastly, the controlled — as opposed to random — nature of a large proportion of violence in the country.

South Sudan is often described in the language of state failure, and regularly appears at the wrong end of lists of failed or ‘fragile’ states (e.g. Fragile States Index, 2021). Yet South Sudan does not have a state which can straightforwardly collapse, given that the political infrastructure of the country is built around a complex and sometimes rivalrous military and security network. Rule by military governments and their affiliates has deep roots in South Sudan, and has been reproduced in militarized rebellions since the 1950s, with rebel forces deploying violence in increasingly similar ways to the government they were fighting.

Parts of this military core extrude into the civil service and political party system, while also permeating South Sudan’s political economy (Astill-Brown, 2014; AU, 2015). This system has been in a process of continued evolution since the CPA was signed in 2005, with the Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA, the military wing of the SPLM/A rebellion, and known since 2018 as the South Sudan’s People’s Defence Forces, SSPDF) developing into a vast and unevenly qualified national army. Reform-minded commanders and military elites confronted numerous difficulties, ranging from efforts to separate the military from civilian branches of the state to resolving incompatible objectives such as integrating militias while addressing pressure to downsize the increasingly large and expensive army (Rands, 2010; Snowden, 2012). SPLA expansion was financed by oil revenues, with a portion of this money being directed to co-opt potential sources of danger from renegade commanders and bring these commanders and their forces into the system, in a process which increased the overall risks the army could pose to society in the event of a collapse in loyalty (de Waal, 2014; Lacher, 2012; Weber, 2013). These risks were increasingly offset by the establishment or empowering of specialized units of the army, paramilitary groups, and the NSS.7The NSS has become an increasingly critical instrument for President Kiir to maintain control since its establishment in 2011. In addition to internal policing, intelligence gathering, and collaboration with counterparts in the region, the NSS functions as a praetorian guard to the regime thanks to its sizable Operations Division (Adeba, 2020). Its military power is sustained by connections to business and the oil sector, and the NSS is prioritized when salary payments are apportioned to the security sector.

This military system can reproduce itself by occupying relatively little territory, provided the capital city, critical garrison towns, and revenue-producing areas are under the control of the government or allied forces, and that good relations are maintained with neighboring countries to avoid external sponsorship of rebel groups in remote and/or border areas. As long as these conditions are met and critical components of this military and security apparatus have a vested interest in staying within this system — and that disputes between factions are kept within tolerable limits, or else help maintain the equilibrium of the system — then the regime is capable of exerting a degree of overall control over this military apparatus. These conditions are more easily met when elites at the apex of the system are able to compensate for the limitations in their authority by ensuring that their rivals squander their own authority in disputes among themselves, rather than uniting against the regime.

As Jairo Munive (2013: 13) observes, “South Sudanese politics are interwoven with low intensity warfare, inter-ethnic violence and, most predominantly, forms of authority grounded in violence – a violence that is performed and designed to generate loyalty, fear and legitimacy within a region or an ethnic group vis-à-vis those in power.” One consequence of this is that President Kiir and his inner circle need to be careful when attempting to assert their authority, in case they end up exacerbating tensions to a point where cannot be easily contained, or provoke commanders into taking actions that are not in the interests of the regime. This is easier said than done, and the process of learning when not to use violence (or to use only limited violence) in the pursuit of objectives has been an inconsistent one. Moves by the regime around President Kiir which seriously disadvantage senior elites — and put them in an untenable position in relation to the ethnic communities they represent — are dangerous, and have the potential to unite factions against the regime, or spark defection and rebellion. Additionally, providing more aggressive elites with openings to expand their power — or permitting these elites to build excessive concentrations of power within certain units or branches of the security sector — can also leave the regime in a vulnerable position vis-à-vis these empowered elites.

The unusual structure and durability of the political system of South Sudan means that, as a rule of thumb, only certain forms of violence have the potential to destabilize it. Raging conflicts in parts of the country (including ones close to the capital city of Juba), have been able to continue without serious attempts on the part of the government to intervene because they are so unthreatening to this system, and potentially divert violent activity away from government strongholds. Many of these could be described as “sovereignty neutral,” with conflicts rarely approaching the level of “sovereignty challenging” violence (Naseemullah, 2018). Indeed, certain forms of violence can strengthen the regime’s control over the country.

As indicated above, violence that most seriously threatens the system comes from within the system itself, in the form of a coup or a defection from commanders with forces near strategically important areas. Violence that strengthens the system includes the (re)capture of strategically significant territory, which in the previous two years is typically accomplished by encouraging an opposition commander to defect to the government. Conflict and violence which has only a limited effect on this system would include the majority of clashes and attacks involving irregular militias.8A partial exception can be found in militia violence which is designed to keep the government away from territory they are not welcome in.

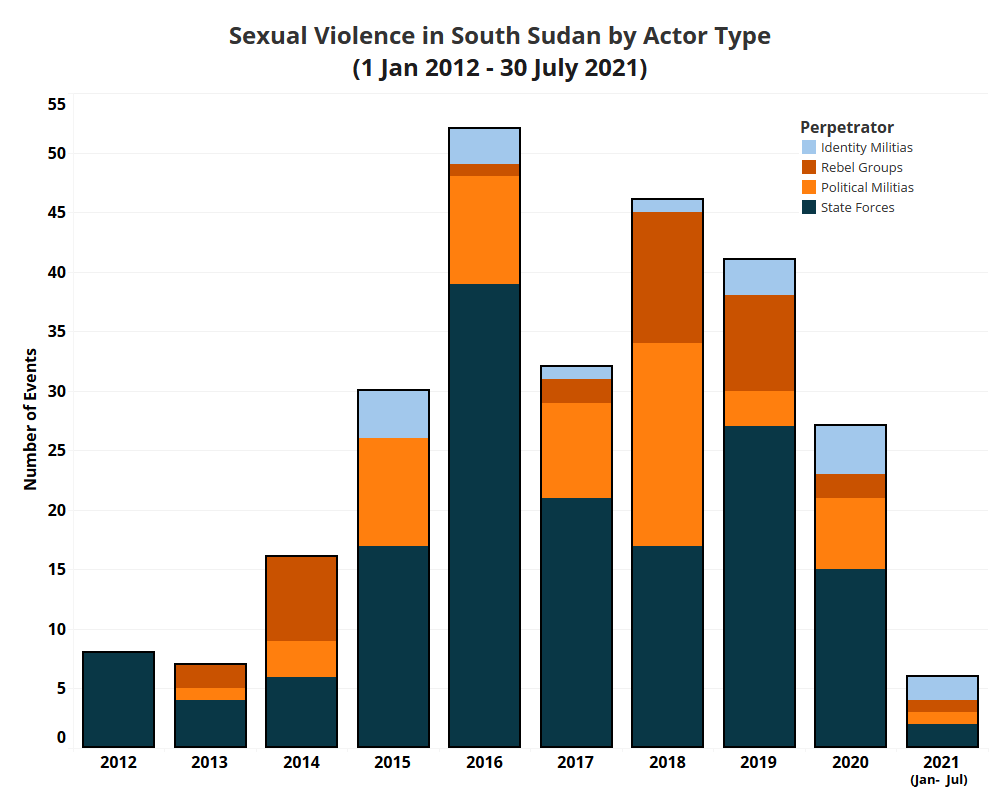

Although most of the violence in South Sudan since R-ARCSS poses little or no risk to the regime in Juba (a point that will be returned to later), it continues to have serious consequences for civilians caught up in it. During times of civil war and counter-insurgency, warring parties will frequently engage in the collective punishment of communities believed to be supportive of the opposing size. Massacres and systematic rape soar during counter-insurgency campaigns, and forced displacement becomes an objective rather than byproduct of war. While massacres and mass displacement are also associated with violence involving irregular militias, it is less clear whether rape and other forms of sexual violence are as common during ‘communal’ violence organized around ethnic or sub-ethnic lines when compared to violence involving conventional military actors. Sexual violence does occur in a number cases of ‘communal’ violence (and particularly during attacks on Pibor in 2020, as discussed below), although ACLED data show the most sexual violence incidents in the time period covered were perpetrated by organized military and rebel actors, and particularly SSPDF soldiers and pro-government militias (see chart below).

The general complexity and unpredictability of violence in South Sudan, particularly when involving irregular forces, reinforces the notion that conflict is largely random. Yet this is a system which is built upon military foundations, with violence and threat of violence integral to its functioning (de Waal, 2014: 348). A system built in this way is likely to become relatively adept at controlling patterns of violence, and eliminating dangers as and when they emerge. The phenomenon of targeted killings euphemistically attributed to ‘unknown gunmen’ by authorities have been linked to death squads of the NSS (UN Panel of Experts, 2019a: 17), with violence internal to the security system likely to be the result of manipulation between rival elements by the intelligence services. Further, and as will be discussed below, security forces are often implicated in acts of ‘communal’ violence, especially large-scale clashes with several rounds of attacks.

With regards to irregular or inter-ethnic violence, it should be recalled that military and political elites frequently outsource violence and security provision to paramilitary groups (Global Witness, 2018; Craze, 2019), replicating the ‘militia strategy’ of Khartoum (de Waal, 1993). In other cases, low-priority areas are deliberately abandoned to irregular militias, who fend for themselves with minimal official support (Schomerus and Rigterink, 2016). Conflicts involving irregular militias often appear patternless or without an obvious cause. This is a problem which is compounded by a lack of detailed information and misplaced assumptions about group structures and motivations (Breidlid and Arensen, 2017), but also because of assumptions about the dynamics of fighting which can become projected onto these. Violent incidents such as these typically take place at irregular tempos, and there can be long delays between initial attacks and reprisal raids, making it harder for observers to form a clear sequence of events. Deadly violence involving the Murle and neighboring groups in Jonglei state (discussed below) can be dormant for years before escalating rapidly. In other cases, the sequence of causes and effects are far from straightforward, and defensive actions can be misinterpreted as offensive ones.

Re-assessing ‘Communal’ Violence

In the South Sudanese context, whenever the term ‘communal violence’ is invoked, this typically alludes to unpredictable activity by irregular militias from an ethnic group (or segments of an ethnic group) attacking rival groups over cows, land, or a border dispute. At times, these conflicts are understood to escalate and spiral out of control, at which point more material grievances are subsumed into ethnic ones. The term conjures anarchic imagery of scrappy groups of young men armed with Kalashnikovs meting out rounds of punishment in rural areas untouched by state authority, in what are ostensibly lateral conflicts between contending ethnic units.

These are an unfortunate set of tropes, in which the forces and structures which regulate, permit, or intensify such conflicts go mostly unrecognized. As with most stereotypes, there is a kernel of truth buried at their core, which has over time been exaggerated or distorted. In South Sudan, state authority is indeed uneven in scope and sometimes erratic in application, and violent conflict is often organized around ethnic lines for reasons discussed earlier. Conflicts also tend to circulate around social, political, and economic assets, or otherwise assume an important socio-political function specific to certain ethnic groups (some examples of which are discussed below). Yet lurking closely behind such conflicts are various agents of power — be they state, rebel, or customary — who have capabilities to engineer or discourage these conflicts. The notion that such forms of violence are unrelated to the state or to national-level conflicts is regularly repeated by South Sudanese military elites, who tend to draw distinctions between ‘government wars’ and violence within communities, even as they have made extensive use of militias raised from these communities in the pursuit of ‘government wars’ (Pendle, 2018: 100).

These distinctions serve to separate ‘communal’ violence from the political history of the country they take place in, and can make such violence appear as though it takes place on a separate plane to more conventional conflicts involving military forces. Yet many of these conflicts have evolved into their present form as a result of decades of war between larger blocs seeking political control of what became South Sudan. These blocs have engaged in successive rounds of ethnicized recruitment, with elites often arming militias to meet their personal objectives or to offset shortfalls in the capacity of forces formally under their command. This has helped to build both an infrastructure and a familiar set of practices for recruiting and deploying militias, which military elites can revive when it suits their interests. Although current forms of militia mobilization were largely developed during the Second Sudanese Civil War (1983-2005), they reflect a history in which commercial and military elites have sought to privatize violence in the pursuit of their interests (Hutchinson, 2001; Johnson, 2009; Thomas, 2015). Imposing authority in South Sudan has historically been a gruelling (and sometimes futile) task, and the widespread use of these militias in the South Sudan of today suggests these militias serve as a shortcut for elites seeking to carve out their authority.

In addition to downplaying (if not writing out altogether) involvement by state and rebel actors, the term ‘communal violence’ also obscures the multiple forms of violence which are often lumped together within it. Rather than drawing a sharp distinction between state and non-state violence – with communal violence being lumped into the latter – these types of violence can be unpacked and situated on a continuum with lesser and greater association to national-level conflicts and its agents. The figure below does this, while separating these into three sub-categories at different points on this continuum: ethnicized revenge attacks; subnational authority contests; and elite proxy wars.

Violence in South Sudan has often (and perhaps questionably) been described as being cyclical in nature. To the extent that this is true, it is arguably better to understand there being cycles in which violence repeatedly transforms from conflicts that feature little or no elite or state engagement, into deadlier epochs driven by elite interests or divisions relating to national-level conflict, and then back again (as can be seen in much of the violence in Jonglei and Warrap states, discussed below). Elite engagement in conflicts involving irregular militias have tended to intensify conflicts, and to reorient them around issues of significance to elites (such as administrative boundaries, access to resources, or the destruction of forces loyal to a rival elite). After elites disengage from these conflicts, subsequent violence in the same areas may well proceed along similar lines and around similar issues to conflicts organized around elite interests, and this violence can itself be re-intensified when contending elites deem it in their interest to do so. Militias which have been mobilized by elites can behave in hazardous ways in and around their home areas, while some militias may be integrated into the regular army, allowing elites to extend their power in the security systems of the country.

This interplay between elite agendas and simmering violence in provincial areas has become particularly noticeable since the 1990s, resulting in larger clashes involving more heavily armed militias in several parts of the country. The most intense and widespread violence will typically accompany the proxy wars of national military and security elites, which can drive violence and displacement across large areas. Equally intensive but spatially concentrated pockets of violence often surround struggles between mid-level military commanders operating in their home regions. Whatever scale such elites are operating on, they thrive on the discontent they create within their communities, or between these communities and neighboring groups.

Additionally, conflicts often have elements associated with several different subcategories, or fuse these subcategories together. The examples on the figure above are situated in sub-categories that bring out the signature features of the violence, even if a case can be made that most of the examples have elements of all sub-categories. As will be discussed in the final section, the dynamics and intensity of conflicts can shift in response to national-level conditions and alterations in the underlying political economy of the country. Almost all conflicts are directly or indirectly connected to the overarching relationships between the military state and society, and the often starkly unequal relations between different ethnic groups in accessing power. The remainder of this section will explore these different forms of conflict and illustrate their specific dynamics with case studies from across the country.

Ethnicized Revenge Attacks

On the left-hand side of the continuum are “ethnicized revenge attacks.” This encompasses some of the main forms of violence which have caused alarm over the past year and a half, including cattle raids, reprisal attacks, as well as large-scale attacks and counter-attacks which closely resemble ethnic cleansing. A signature characteristic of these conflicts is their rhythm and trajectory: they begin with a small raid or clash, which can swiftly escalate into rounds of more intensive and concentrated fighting that dramatically raises the numbers killed and wounded. In the aftermath of serious clashes, violence tends to fizzle out, with score-settling killing fewer people and in more disparate locations. This dynamic occurs, in part, because of problems in seeking effective legal redress for the initial act of violence, and (as shall be discussed later) due to actions by security services and their elite which aggravate such conflicts.

Rather than describing these conflicts as tribal or ethnic, the term ethnicized is used instead. This is in recognition of the fact that conflicts which are organized or mobilized along ethnic (or clan or sectional) lines are not synonymous with ethnopolitical conflicts. These lines are blurred in some cases, with violence in Jonglei state in particular oscillating between these poles after the signing of the CPA in 2005.

The violence in Lakes state is often held to be revenge-based in nature, and will be explored in more depth below. Conflicts which have a strong retaliatory element are common across much of South Sudan, though outside of Lakes these have tended to either coexist with or be subordinate to other dynamics which surround violence in these areas. Examples of these conflicts — including in Eastern Equatoria and Central Equatoria states — will be discussed in the forthcoming second analysis piece, while revenge attacks in the contexts of elite proxy wars will be discussed later in this analysis. While prominent national elites have hailed from Lakes, violence within this state is influenced more by developments within and between societal rather than state actors. This is not to say violence in Lakes is unrelated to the developments at the national-level. Indeed, national political and economic turbulence — and the purposeful erosion of justice mechanisms — has enabled violence to spread unchecked in much of the state. However, conflicts in Lakes state are primarily initiated and maintained by actors who have loose connections to the antagonists of national conflicts.

Lakes State

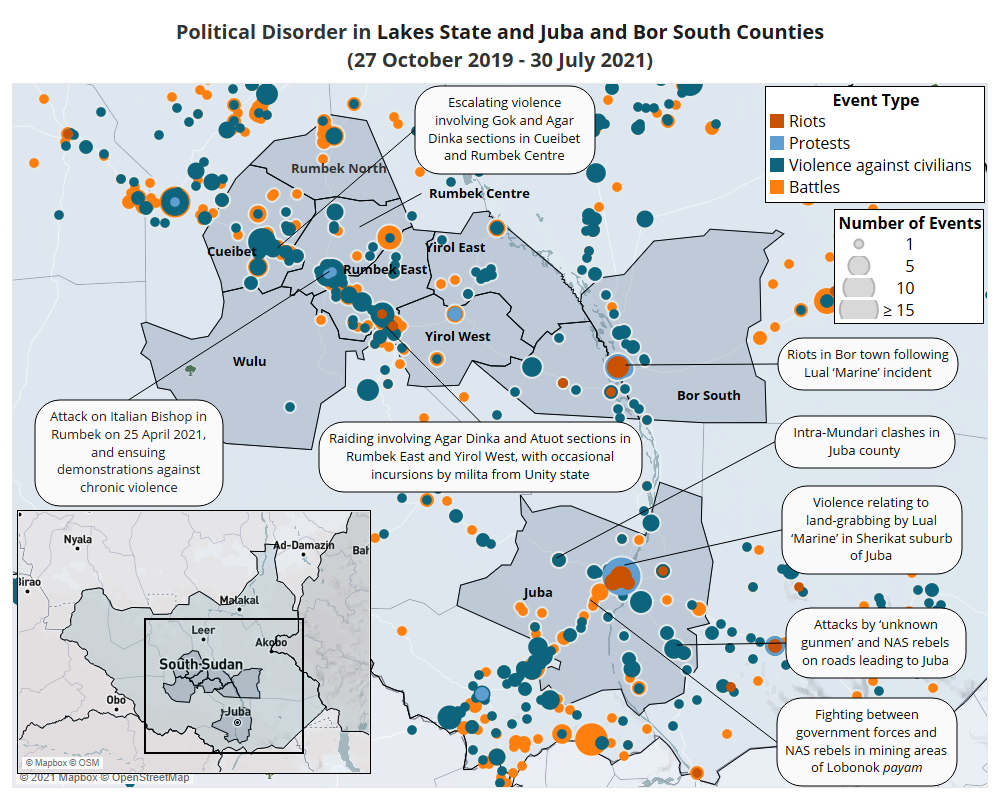

After the signing of R-ARCSS, serious violence has once again engulfed much of the central belt of Lakes state — from Cueibet county to the west to Yirol town to the east, via Rumbek Centre, and Rumbek East counties — and has increasingly spread to parts of Awerial, Wulu, Rumbek North, and Mvolo counties. Violent disorder among sections and subsections of the Agar and Gok Dinka clans in the Greater Rumbek area is not new, and was a significant factor in the late SPLM/A leader Dr. John Garang’s decision to retain Juba as the capital of South Sudan, instead of moving it to the SPLM/A stronghold of Rumbek (Young, 2021: 155-56). Intense violence among and between Agar Dinka sections of the Greater Rumbek area, and those of the Gok Dinka of Cueibet county (and at times the Ciec Dinka and Atuot of the Greater Yirol area), has also flared up during the course of South Sudan’s recent civil war.

Since 2020, a number of reprisal attacks, raids, and counter-raids have rocked Lakes state (see map below). These attacks tend to subside after a particularly intensive bout of fighting. Some of the deadliest incidents include the following that took place during the dry season and early into the rainy season.9The dry season usually begins in November and ends in April, though there is some variation here. Due to the difficulties of movement of military personnel and vehicles during the rainy season, and the tendency for disputes and raids among pastoralists to increase while sharing dry seasonal grazing lands, the dry season in South Sudan is typically associated with greater levels of violence than the rainy season. This distinction has become less pronounced in recent years. Although it is possible that the presence of more advanced forms of military transportation and slightly improved infrastructure account for some of this shift to year-round violence, this may also be a result of the declining significance of traditional agriculture and cattle migration in South Sudan’s economy. In previous decades, soldiers would often relocate from frontlines to their home areas to farm or graze cattle during the rainy season, which reduced the capacity for belligerents to engage in large military operations. In late January and early February 2020, clashes between parts of the Athoi and Rup sections of the Agar Dinka clashed in Rumbek East county, reportedly killing 53, and wounding 40. In mid-March, fighting among various Agar Dinka sections in the Marial Bek area of Rumbek East county in response to the killing of two elderly men at a cattle camp reportedly killed over 40 people and wounded approximately 60 people. In response to a gang-rape in early May, subsections of the Macar section of the Gok Dinka clan clashed in Cueibet county, with at least 14 reported killed in one round of fighting and 15 killed in another round a week later. In late June, intersectional clashes among the Agar Dinka clan killed at least 33 and wounded a similar number in the Meen Waal area of Rumbek East, in response to escalating violence between the groups.

Attacks and reprisal raids resumed after the end of the 2020 rainy season. On 9 December, fighting broke out among Gok Dinka sections (with SSPDF reportedly involved in the clashes) in Mayath in Cueibet county, after the county prison director was killed on 8 December. The fighting killed 15 and wounded at least 17. On 8 March 2021, members of the Pakam section of the Agar Dinka (based in Rumbek North) clashed with sub-sections of the Macar section of the Gok Dinka at a cattle camp in the Ngap area of Cueibet county, killing between 17 and 24, with a large quantity of cattle reported stolen. On 18 April, fighting among subsections from the Athoi section of the Agar Dinka in Rumbek East county killed 23 and wounded 20, and resulted in a number of arrests of individuals accused of supplying arms. On 22 April, clashes involving two Atuot sections in Anuol payam10Payams are the third highest administrative level in South Sudan, above bomas, but below states and counties. of Yirol West county killed at least 20, and were reported to be linked to a smaller clash in March which related to an elopement. Finally, on 21 June, armed pastoralists from the Pakam and Rup sections of the Agar Dinka attacked members of the Gok Dinka at Makerdhiem cattle camp in Cueibet county, killing at least 24 and wounding 25.

These incidents are typically escalations of recurrent low-level violence, and at times suck in members of the security services (Radio Tamazuj, 11 December 2020; Juba Monitor, 29 May 2021). Many clashes involve significant numbers of cattle being stolen, some of which are later recovered by armed youth or authorities. At times, these clashes have taken place on the outskirts of Rumbek town, and while fighting involving armed youth occurs within Rumbek town itself. The shooting of an Italian bishop in Rumbek in April 2021 is one of the more high-profile incidents of violence in the area (Radio Tamazuj, 26 April 2021), although the motivation for the attack remains unconfirmed at the time of writing.

There is little evidence to suggest these conflicts are directly or closely connected to national-level politics, while suggested links between raiding and subnational politics tend to be rooted in speculation and rumor. However, this is not to say that revenge-based conflicts involving cattle are apolitical or disconnected from the wider political economy of South Sudan. Violent cattle raids and reprisals have accompanied growing distortions in wealth which have concentrated cattle ownership in fewer hands, as structures which permitted a relatively stable and dignified livelihood in cattle camps have been hollowed out. Significant economic changes underway in recent decades have unshackled some of the informal institutions and networks of economic assistance which have supported parts of the rural economy (Thomas, 2019). Meanwhile, war and the introduction of market imperatives has caused further dislocation to the point where a life in cattle camps offers young South Sudanese an existence that is “precarious, insecure and entrapping” (RVI, 2021: 27).

Importantly, these economic changes have contributed to the erosion of justice systems, and have created imbalances which have undermined cattle-based compensation systems that had previously been reasonably effective at deterring deadly raiding and revenge killings. In specific areas of South Sudan, the acquisition of very large herds of cattle by wealthy elites (often based in Juba and/or are members of the diaspora) has been linked to both violent cattle raiding by cattle keepers employed by elites as well an inflation of bride prices, which has caused disequilibrium in cattle compensation payments systems. Fixed compensation payments which evolved over the past century were based in part on ensuring that relatives of those who engaged in deadly raiding would share the negative consequences of their actions along with the victims, through having to make substantial compensation payments in the form of cattle. The penalties and reciprocity which underpin this system are undermined when relatives of attackers possess very large quantities of cattle wealth, rendering fixed compensation payments essentially meaningless (Pendle, 2018: 111).

As Naomi Pendle and Gatwech Wal (2021: 17) argue, the absence of effective and impartial justice mechanisms may go some way to explaining the prevalence of revenge attacks in Lakes state:

“These conflicts have been dominated by revenge killings. Revenge is not simply a result of hot anger, nor a product of out-of-controlled, uneducated youth. They are also not the result of ancient hatreds, but are rooted in contemporary politics. Revenge often has a popular moral value linked to a demand for justice, and this value is reshaped and contested over time.”

Further, the authors note how these conflicts are (like many in South Sudan) indirect consequences of administrative and boundary reforms (ibid.: 18-20). The capture of local administration by prominent elites (who typically have customary and/or military power) further complicates matters of justice, encouraging yet more lawlessness. The violence in Lakes state has been compounded by violence in neighboring states, with cross-border violence involving militia and cattle raiders from southern Warrap state becoming increasingly deadly (discussed below). Further south, Agar Dinka and Atuot militias have been implicated in a number of violent acts in northern areas of Mvolo county in Western Equatoria state. Cattle raiders from Panyijiar county in Unity state have become notably active in adjoining parts of northern and western Lakes state (e.g. Eye Radio, 20 July 2021a), with the Small Arms Survey (2021a) drawing links between the absence of legitimate authority in southern Unity state (following the appointment of unpopular county commissioners by the SPLM-IO) and deteriorating security.

These factors would suggest that military-led crackdowns and rapid executions of suspects (which are believed to be favored by the newly appointed Governor of Lakes state and former Director of SSPDF Military Intelligence, Major General Rin Tueny) against cattle raiders are really addressing the symptoms rather than causes of the problems in Lakes state. Moreover, these may accelerate the bypassing of the judiciary and encourage abuses by the security services, fueling grievances which may come to undermine stability in the longer-term.

Revenge killings and raids in Lakes state have not generally been directed against the political structures in the state or towards those in senior positions in local administration, even though the violence reflects some of the deficiencies and injustices of this system.

Subnational Authority Contests

In the middle of the continuum are “subnational authority contests,” which typically take the form of warlordism or politico-military struggles for power in areas away from the capital. The carving out of fiefdoms by military commanders has been a recurrent feature of South Sudanese military politics over the past century and a half (Craze, 2021; Johnson, 2009). This has usually entailed consolidating control of people and resources through building a sizable armed militia (or autonomous unit within a larger armed bloc) to project power, while taking a cut from commercial and sometimes humanitarian activity in their domain. In recent decades, such strongmen have typically come in hostile pairs (and sometimes in a hostile trio). As a more powerful commander consolidates control of a territory and local networks, resentful contenders wait in the wings, casting a line for external military or financial assistance before making their move when the next crisis or political shift presents itself.

This process — though risky — has long been a reliable route to exerting considerable influence upon subnational politics. However, the oil boom from the early 2000s to 2012 increasingly enabled governments to provide such individuals with financial inducements or senior military or political positions, bringing them into the orbit of national politics (usually in the form of a position as a commissioner or ideally a governor, or as the commander of an army division stationed in their home area). The collapse in available oil revenues during the recent civil war — as well as rounds of administrative redivision which curtailed the power of governors and county commissioners from late 2015 to early 2020 — have helped put this system into reverse.

One consequence of this is for there to be heightened competition among such commanders to build (or rebuild) an apparatus to extract resources and exert dominance in their home areas, instead of relying upon declining and irregular funds from Juba. The ending of the civil war has presented such figures with modest opportunities to consolidate their gains from war, often via defecting to the government. In addition to the examples discussed below in relation to Western Equatoria state, Major General Moses Lokujo in Kajo-Keji county of Central Equatoria state and Major General James Ochan in Maiwut county of Upper Nile state have both engaged in similar practices of defection to consolidate war-time gains. In other cases, politico-military elites have sought to project power from the national-level into their home areas, further militarizing ethnopolitical disputes in these regions (as has happened in both Upper Nile and Unity states, which will be discussed in more detail in the forthcoming second analysis). In both cases, escalating violence tends to be the outcome.

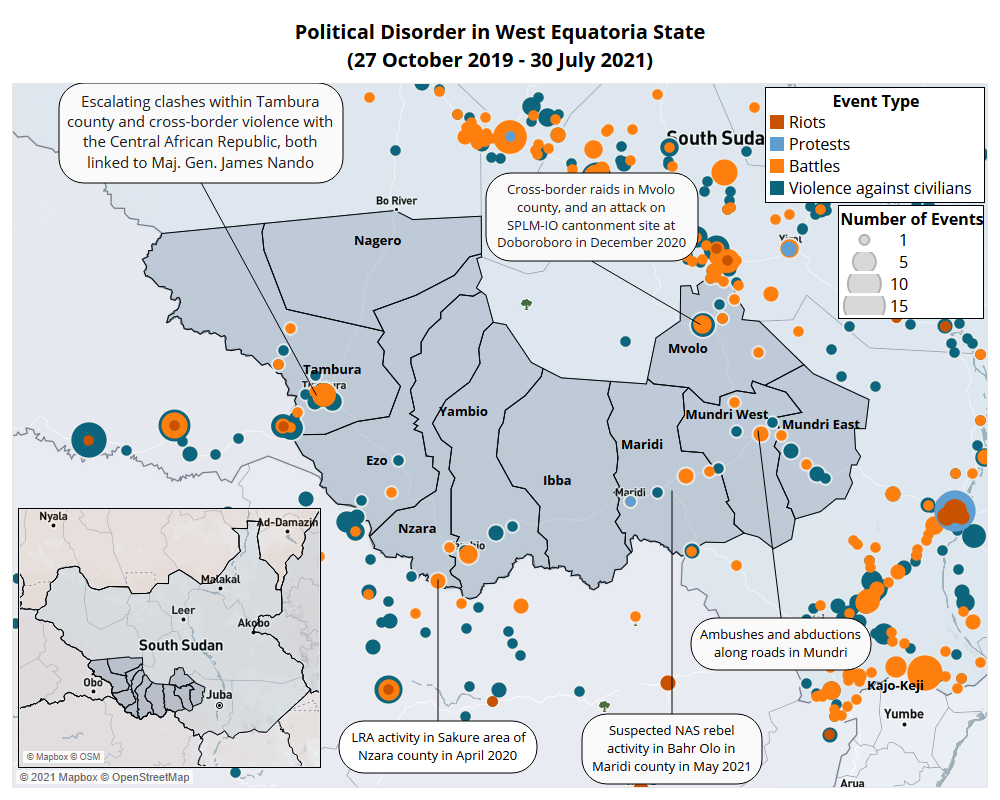

Western Equatoria State

During the second half of the latest civil war (specifically from late 2015 to early 2018), several relatively obscure individuals from Western Equatoria with connections to local self-defense militias found themselves rapidly promoted to senior positions in the SPLM-IO. This coalition of rivalrous commanders, who were ostensibly part of the same rebellion, led unevenly trained and poorly equipped forces against an intensive counter-insurgency campaign conducted by the government under the banner of the IO (Boswell, 2017; Braak, 2020). Their rise was facilitated by a perfect storm fueled by simmering resentment at the SPLM government among much of Western Equatoria’s population, continued abuses by Dinka pastoralists in parts of the state, and increased opportunities for rebel recruitment presented by the flawed cantonment process under the 2015 peace agreement (Small Arms Survey, 2016). These events set in motion a brutal conflict in the state that had the outward appearance of being between the SPLM-IO and government, but which on closer inspection often resembled a set of inter-elite conflicts mobilized around ethnicity. These elite agendas were not necessarily in line with those adopted by their parent organizations, with certain rebel and government elites appearing to share similar objectives.

These inter-elite conflicts were dormant between the signing of R-ARCSS in September 2018 and the appointment of the Transitional Government in February 2020, though have gradually intensified since this time. This began with the defection of Major General James Nando (an ethnic Zande), who was the SPLM-IO commander of Division 9B until March 2020 when he jumped ship from the IO to the government. A number of other senior IO commanders also defected around this time, some of whom who felt spurned by Dr. Riek Machar’s refusal to appoint them to senior positions, after he chose to appoint family members and obscure politicians (whose obscurity and lack of influence in their communities would render them dependent upon Machar) to these positions instead.11Other notable commanders included Lieutenant General ‘CDR’ James Koang (a respected commander from Upper Nile state, who had good working relations with the military before and after the conflict) and Joseph Albiros Yatta (the commander of SPLM-IO Division 2B in Central Equatoria). In other cases, there were multiple rival commanders vying for the same posts, causing resentment among those who went unappointed.

This was likely the case with James Nando, who rebelled following the appointment of his rival and superior officer, Lieutenant General Alfred Fatuyo as IO Governor of Western Equatoria (UNSC, 2020: 5). Fatuyo is half-Balanda and half-Zande, is illiterate, and was responsible for turning parts of the Arrow Boys (an anti-pastoralist and anti-Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) network of militias) into a poorly organized rebellion as the war moved to Western Equatoria (Small Arms Survey, 2016). It is also probable that another senior commander, Lieutenant General Wesley Welebe (an ethnic Moru, from the eastern area of the state), was frustrated with the appointment of Fatuyo (Small Arms Survey, 2020). Welebe has kept a low profile since this time.

Nando’s defection further strengthens the position of the Avungara clan of the Zande, whom Nando and the (long-standing) Acting Secretary General of the SPLM party – Jemma Nunu Kumba – hail from, as does the recently appointed deputy governor of the state. This is part of a sub-surface power struggle among different branches of the Zande in Western Equatoria, who seek to limit the influence of the SPLM-IO Governor Alfred Futiyo and his ally Joseph Bakosoro (the popular former independent governor of the state, who controversially returned to the SPLM fold this July) (Small Arms Survey, 2020). Nando has reportedly recruited a new militia since his defection, which has been implicated in violent events in the far western county of Tambura, as well as cross-border violence in the Central African Republic (CAR) (Small Arms Survey, 2021b).

On 17 June 2020, SSPDF and Zande militiamen attacked SPLM-IO forces at their cantonment site Namutina in Tambura county, killing an IO Brigadier General and at least ten IO soldiers, and displacing over 5,000 people. These attacks are believed to have been orchestrated by Nando, who was subsequently summoned to Juba (UNSC, 2020: 5).

Violence flared up again in April 2021, with clashes between unspecified ethnic groups (likely Balanda and Zande) being reported in Tambura county, displacing around 800 people (UNOCHA, 7 May 2021). A spate of targeted attacks on civilians in and around Tambura town were also reported at the start of April. In June, eight people were killed in western areas of the county, in what have variously been described as inter-ethnic conflicts, or proxy wars involving both opposition and government aligned forces (see map below). Then, on 17 and/or 18 July, fighting was reported in Tambura town itself, displacing thousands. This included an attack on the residence of the Paramount Chief (Eye Radio, 20 July 2021b; Radio Tamazuj, 21 July 2021), which was in all likelihood conducted by forces loyal to James Nando. Violence then spread to a number of villages on 19 July, though only limited information is available on these incidents (Radio Tamazuj, 22 July 2021). The UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (6 August 2021) has estimated that around 150 people were killed in the July clashes. It is not clear that these conflicts straightforwardly align with political divisions between the SPLM-IO and government, nor that these are primarily ethnic in character. It is more likely these reflect ongoing complex rivalries between commanders and politicians which cut across the rebel-government divide, who have sought to project these disputes onto their ethnic communities.

James Nando has also been implicated in cross-border violence since late 2020. These clashes pitted Nando’s forces against Central African rebels from the Union for Peace in the Central African Republic (UPC) in eastern parts of Bambouti prefecture in November 2020. This has been followed by a spate of isolated attacks against civilians in the border areas of Tambura county and Bambouti, particularly around Source Yubo and nearby Bambouti town. Precise information is limited, though the attacks into the CAR by Nando’s forces appear to follow incursions by the UPC into South Sudan (including Nando’s hometown), and in particular to the monopolization of cross-border trade and taxation by parts of the UPC (UN Panel of Experts, 2021a: 114-115, 131). While Nando’s forces are ethnic Zende, the UPC fighters they have been clashing with are mostly ethnic Peuhl (Human Rights Watch, 2017).12This author would like to thank Maya Moseley of Invisible Children for noting an error in the original version of this report (released in August 2021), which had incorrectly stated that the UPC were ethnic Zande. Note that the Peuhl are also known as the Mbororo or Fulani (Minority Rights, 2018), who have often had tense relations with farming communities in Western Equatoria in recent years. James Nando has recently alleged that Mbororo pastoralists are fighting alongside the Balanda and SPLM-IO in Tambura (Radio Tamazuj, 6 September 2021).

In addition to cross-border violence into the CAR, there have been frequent reports of incursions by South Sudanese men in military uniforms into parts of the DRC since April 2020. Many of these incursions have been accompanied by looting (suggesting that these are being perpetuated by soldiers who are unpaid), though the torching of homes and markets, sexual assault of women, and occasional clashes with Congolese security forces are also reported with some regularity. These activities have been concentrated in Faradje and especially Dungu territories in Haut-Uele province, and Aru territory in Ituri province. At times, South Sudanese authorities have attempted to explain incursions into Aru territory as resulting from SSPDF efforts at pursuing NAS rebels into the DRC, though no explanation has been offered for looting and violence further to the west from the government and/or rebel groups who may have been involved. A final cross-border event of note occurred in February 2021, when a breakaway NAS commander — Major General Saki James Palaoko — was killed in Haut-Uele province (possibly in the Meri refugee camp close to Aba town). Details are vague, though some reports have linked the killing to another breakaway faction from NAS.

Elsewhere in Western Equatoria, NAS rebels have been implicated in a series of attacks against road contractors and military vehicles in the eastern half of the state, as well as an attack on an SSPDF barracks in Maridi county in May 2021. Finally, there have been reports of limited LRA activity in Sakure in Nzara county in April 2020 (Crisis Tracker, 2020), and potentially in southern Yambio county. Once a hotbed for LRA attacks, local resistance from Arrow Boys and the retreat of the LRA to politically inaccessible territories in the wake of Ugandan counter-insurgency activities in South Sudan and CAR appear to have dislodged the group from the area.

Elite Proxy Conflicts

Factionalism among Southern Sudanese armed elites has been a growing problem since the First Sudanese Civil War, which reached its zenith during the internecine fighting among Southern rebels, militias, and paramilitary forces in the 1990s. Factionalism has often created an enabling environment for warlordism to flourish. Military elites who have credibility or notoriety within their communities are capable of mobilizing youths from their home areas, so long as these elites have access to a source of wealth and weaponry. Through providing youth with resources, self-respect, and a degree of security to the communities they come from, military commanders can render youth partially or wholly dependent upon them, while utilizing their new militia to advance their interests against other elites. In many areas, the toxic residue of elite rivalries and factionalization can be seen in lawlessness, ethnicized competition over resources, and the dislocation and wearing down of justice and mediation systems which previously limited violence.

This factionalism has been reproduced in the post-CPA era government, and lingers within the government and SPLM-IO in the aftermath of the most recent civil war. Although warlordism does still occur, it is now restricted by tighter government control and more limited resources, and tends to be concentrated in specific areas (often close to South Sudan’s international borders, as has been seen in defections in Kajo-Keji, Maiwut, and Tambura counties). Elite proxy conflicts are now more closely controlled by state security actors, and some larger rebel factions.

Alex de Waal (2021) disaggregates several forms of state collapse, identifying a “security perimeter state” that emerges “when a minority entity… has both military power and motive to seek permanent security by preventing the emergence of an alternative power center that might threaten it.” Post-war South Sudan strongly resembles such a state, even if its military power is increasingly undermined by its economic problems. One of the ways in which elites close to the regime seek to maintain control is through influencing or exploiting events so as to weaken opponents, who can be expected to resist such efforts.

In South Sudan, elite proxy wars take several forms. The most common is for rival elites to establish militia or paramilitary forces, and to direct these militias to either destabilize an area linked to a rival elite or elite faction, or to enhance their degree of control over their own areas. Military elites can also divert organized forces to meet the interests of a constituency who’s loyalty the regime depends upon, or to pressure their elite rivals into submission. Some of the most serious forms of elite proxy warfare occurs when military forces are deployed to engage in punitive ‘civilian disarmament’ campaigns against militia forces loyal to elites who are deemed to be a threat to the regime. The cases below illustrate examples of proxy wars aimed at addressing threats from within the regime (Warrap state) and exploiting a crisis to limit the regime’s exposure, while ensuring that dangerous elements attack one another instead of the government (Jonglei state). Warrap and Jonglei states have been two of the most violent areas of South Sudan since the signing of R-ARCSS due to recurrent militia fighting and raiding. These conflicts, which had mostly been fought between irregular clan militias, have become markedly more in 2020 once elites became more closely engaged with them. Small-scale raids and counter-attacks have been supplanted by larger and more organized warfare, involving operations which increasingly resemble conventional military operations.

Warrap state

Since the death of Dr. John Garang in 2005, power within the SPLM/A gradually transferred away from Garang loyalists to Dinka from the Greater Bahr el Ghazal region, and particularly Rek Dinka from Warrap state. President Kiir hails from Akon in Gogrial, while number of senior elites who have assumed leading roles in South Sudanese politics over the past decade are also from Gogrial or Tonj, including Akol Koor, Awut Deng, Tor Deng, Salvatore Garang, and Mayiik Ayii Deng.

The Greater Tonj area of Warrap state (comprising the predominantly Rek Dinka-inhabited Tonj North and South counties, and the more marginalized Luachjang Dinka areas of Tonj East county) was among the most active areas of serious fighting during 2020, killing hundreds. The fighting has continued into 2021, although media interest in the fighting has waned. As was anticipated in ACLED’s November 2019 analysis of South Sudan — Last Man Standing — the escalating tensions among senior Bahr el Ghazal Dinka elites were likely to shift violence towards this area. Much like in Jonglei state (the final case study, discussed below), the violence in Greater Tonj involves collaboration between military actors and irregular militias, and has witnessed such forces engaging in relatively sophisticated military-style planning and operations.

The violence around Tonj is particularly complicated, with violence among irregular militias giving way to more organized violence conducted by elites at the top of the pyramid in Juba. As a general rule, clashes within Tonj North operate at two levels, with the interest of elites (often based in Juba) permeating through these levels (Eloff, 2021: 11-12). In the first of these levels, the Kuachthii and Akop sections of the Rek Dinka have engaged in raids and attacks against one another. In the second level, existing feuds within the Kuachthii (specifically between the Ajak-Leer and Noi sub-sections) and Akop (Apuk Padoc and Awan-Parek sub-sections) sections have entrenched violence in parts of the county. These conflicts have the outward appearance of being driven by disputes over use of grazing land, administrative boundaries, and the acquisition of cattle, and invariably spark revenge attacks by the community targeted over these matters. These conflicts are mirrored in eastern parts of Tonj South county, involving the Muok, Thony, and Apuk Jurwiir sections. Violence has also clustered in and around Tonj town, while occasional reports of cross-border raids from Tonj South into Tonj North emerge.

Meanwhile, clashes between Rek and Luachjang Dinka have been frequent in areas along the border between Tonj East and Tonj North counties, while Luachjang youth have intercepted several humanitarian convoys in the Romic area of Tonj East following clashes to prevent supplies reaching Rek Dinka sections. Luachjang clan militias also became embroiled in raiding in Rumbek North county of Lakes state ( UNSC, 2021: 5).

As in Lakes state, cattle raiding and revenge attacks comprise the majority of incidents, alongside occasional clashes over administrative boundaries and land (see map below). The most serious incidents have left dozens killed, in fighting which involves coordinated attacks by heavily armed militias from multiple sub-sections. Surrounding these recurrent clashes are raids that cross over the boundaries into neighboring states. Militia and armed pastoralists from Warrap have launched attacks in neighboring counties such as Jur River, Rumbek North, and Mayom, sometimes in response to attacks from Bul Nuer and Agar Dinka militias. Particularly high casualties have resulted from Bul Nuer raids at Mayen Jur and Mangolapuk in Gogrial East in May 2020 and May 2021, respectively. In addition, suspected Gok Dinka militias from Cueibet raided Tonj South on 20 March 2020, leading to clashes that killed between 55 and 67 people.