The military coup d’état in Sudan on 25 October 2021 sent shockwaves across the region and through diplomatic circuits. Following the arrest of the civilian Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok and several prominent senior officials from the Forces for Freedom and Change (FFC), demonstrators took to the streets across Khartoum. They were confronted by soldiers from the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) and Rapid Support Forces (RSF) paramilitaries in the capital, with reports emerging of Central Reserve Police paramilitaries also being deployed (Human Rights Watch, 29 October 2021). Over 10 people have reportedly been killed by state forces thus far and over 160 wounded (Radio Dabanga, 29 October 2021; UN OCHA, 28 October 2021), with at least some victims uninvolved in the demonstrations (Eye Radio, 27 October 2021). Demonstrations have since spread across much of Sudan.

The ringleader of the coup — Lieutenant General Abdel Fattah Al Burhan — is the military head of the Sovereign Council, and the commander-in-chief of SAF. On 25 October, he announced that a state of emergency was in effect, and that civilian political institutions established under the Constitutional Declaration of August 2019 would be dissolved. Bodies tasked with investigating the massacre of 3 June 2019 (discussed below) and with dismantling the ‘deep state’ of ex-President Omar al Bashir and the National Congress Party (NCP) were also dissolved (Al Jazeera, 25 October 2021), perhaps tipping the hand of the generals who organized the coup in the process.

By 26 October, amid widespread condemnation at home and abroad, Burhan re-emphasized that the seizure of power would only last until elections in mid-2023, and that Prime Minister Hamdok would be released from custody later that day. While Hamdok and his wife were released that evening, further arrests of civilian politicians and trade unionists were reported (AP, 27 October 2021). On 27 October, Sudan’s membership of the African Union was suspended for the second time since the removal of Bashir in April 2019 (Al Jazeera, 27 October 2021).

The fierce resistance to the coup — and the failure of the coup leaders to forge links with any ideological or politically viable constituency (Berridge, 2021) — suggests that the coup leaders will have to hurriedly cut deals with FFC elites who are prepared to do business with the military, or attempt to ride out the storm of protests coming their way. There is a palpable risk that the political bargain which has stitched together Sudan in the aftermath of Bashir will disintegrate. The prospect of serious violence against demonstrators in urban areas is increasing, while a reorganization or unravelling of alliances between military, paramilitary, and rebel elites threatens to plunge peripheral regions of Sudan into renewed war.

What explains this coup, and what are its likely consequences? This analysis argues that the trajectory of Sudan after the collapse of ex-President Bashir’s regime strongly reflected the realignment of power enshrined in the agreements brokered in the summer of 2019, and the Juba Peace Agreement (JPA) a year later. The 2019 agreements brought together the Transitional Military Council (TMC), composed of senior elites from the security sector who ushered Bashir out, and the FFC, composed of representatives from mainly civilian political groups who negotiated on behalf of a mass social movement that rallied against Bashir from late December 2018 onwards, and established the parameters of the current Transitional Government. Military elites from the new power-sharing government then set about taking the lead role in negotiating the various agreements which comprise the JPA with rebel representatives, giving a lifeline to insurgents whose political allure and military power had been dulled after years of in-fighting and counter-insurgency. The JPA was agreed upon by 31 August 2020, with the final signing ceremony taking place on 3 October 2020. These agreements have facilitated collusion between the signatories of the JPA and military elites, while fracturing the disparate components of the FFC into camps which are prepared to support a continuation of military kleptocracy in Sudan and those which are not.

At best, these agreements and the transition from Bashir have failed to resolve Sudan’s deep political and economic quagmires. The country has complex economic problems which followed from the decarbonization of its petro-kleptocracy. Changes to the executive have been unable to reverse the fragmentation of the security sector or address simmering conflicts in the marginalized peripheries of the country, as discussed in ACLED’s previous reports on Sudan. At worst, these agreements have simply exacerbated these problems.

The coup of 25 October is merely the latest phase of this unfortunate trajectory, and one which pushes the country into a dangerous new phase. All of the ingredients are in place for further violence and instability in Sudan, with diminishing options for containing the ambitions of the assorted military, paramilitary, and ex-rebel factions which have amplified their power since the fall of Bashir.

The first section below explores the growing disenchantment with Sudan’s so-called ‘transition,’ amid political realignments within and between military, rebel, and civilian elements of the Transitional Government. The second section discusses the growing tensions in Eastern Sudan and their connection to these developments, while the third section discusses the potential consequences of the coup for Darfur and the ‘Two Areas.’ The fate of these regions is tied to developments in Khartoum, thus sections two and three outline patterns of violence in these regions since the signing of the JPA in October 2020. This analysis concludes by reflecting on the international and regional responses to the coup, and the prospects for further conflicts in the fractious military apparatus which has seized power, particularly involving Burhan and his deputy Lieutenant General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo (a.k.a. Hemedti, who commands the RSF).1The RSF are a paramilitary force established in 2013 to assist then President Omar al Bashir to marginalize Darfurian strongman Musa Hilal, and to act as a praetorian guard for the regime (Al Jazeera, 6 June 2019). The RSF was partially built out of Janjaweed militias active during the war in Darfur, though Hemedti and his family have expanded recruitment across peripheral areas of Sudan since this time, while also expanding their gold mining operations.

The Prelude to the Coup

As argued in ACLED’s report Danse Macabre, the uprising which began in December 2018 was the delayed response to Sudan’s rapid (and from the perspective of its ruling elite, entirely unwelcome) decarbonization after South Sudan seceded from the country in 2011. The uprising ultimately morphed into a platform for various groups with quite distinct interests and objectives to carve out a space in the post-Bashir order. Activists and trade unions were at the forefront of initial efforts to overthrow the deeply repressive and decaying system of Bashir’s National Congress Party (NCP), and found popular support among many urban Sudanese to replace this system. Urban middle-class constituencies which had previously supported — or at least tolerated — the Bashir regime were also becoming increasingly alarmed at Sudan’s economic trajectory, while the military and security establishment underpinning the regime now viewed Bashir as a liability. Meanwhile, many of Sudan’s traditional political parties and rebel groups swam alongside the revolutionary currents, in the hope of exploiting the upheaval to embed themselves within the political dispensation that would emerge from the toppling of Bashir.

While there was broad support for replacing Bashir, there were obvious disagreements regarding what the new system would look like, who should control it, and who should benefit from it. Further complicating matters was the exasperation shown by demonstrators on the streets towards Sudan’s traditional parties, due to the habitual tendency of these parties to compromise with military autocrats in past decades (Alneel, 2021). After the removal of Bashir on 11 April 2019 by an alliance of senior security and military elites who branded themselves the Transitional Military Council (TMC), demonstrators continued to push for a fully civilian government. These demands escalated following a series of attacks and massacres by security forces (especially the RSF) against demonstrators, which culminated with the killing of over one hundred demonstrators at the sit-in camp near the army headquarters in Khartoum on 3 June 2019. Hundreds were wounded in the attack, with reports of multiple sexual assaults committed by men in RSF uniforms (Human Rights Watch, 2019).

In spite of the obvious dangers of forging a power-sharing agreement with military actors responsible for such atrocities, political negotiators for FFC pressed on with negotiations (facilitated by Western and Gulf powers) with the TMC. The agreements struck between the FFC and the TMC over the summer of 2019 — justified in part on the grounds of pragmatism — laid the groundwork for a form of politics destined to be entrapped between the self-interest of its signatories and the policy guardrails established by international financial institutions with whom the new government would have to negotiate for Sudan’s economic survival. These negotiations also reorganized power within the FFC, allowing a political elite to take the reigns from more radical elements present on the streets. As Muzan Alneel (2021) summarizes, the negotiating climate “produced the current government, which is a military and civil partnership sponsored by the UAE and Saudi Arabia, internationally financed, and staffed by former employees of developmental organizations. This government is therefore an expression of both the economic and political counterrevolutions.” It also incorporated many of the fault lines existing within and between these now paired entities.

As observed by Raga Makawi (2021), the Transitional Government that emerged from these negotiations has quite predictably taken decisions which diverged markedly from the stated goals of many participants of the uprising. Demands which were at the core of the revolution — such as calls for economic and political justice, and for the dismantlement of violent systems of power and wealth extraction — were subverted and sacrificed to the goal of sustaining a power-sharing arrangement by FFC elites who had little obvious connection to the streets. Many of the leading actors within Sudan’s ‘transition’ have pursued austerity policies while presiding over an increasing militarization of the political sphere, with elites from civilian and rebel entities engaged in the reconstruction of kleptocratic and undemocratic institutional structures. Flickers of progress towards tackling corruption and impunity have been met with delaying tactics on the part of military and paramilitary elites. As Alex de Waal (2021) notes, “Not only was the army commanding a vast — and still-increasing — share of the national budget, but military-owned companies operate with tax exemptions and often allegedly corrupt contracting procedures.” If Burhan (or Hemedti) are able to consolidate power following the 25 October coup, efforts to reign in the economic power of the military and bring generals responsible for atrocities to court will be snuffed out altogether.

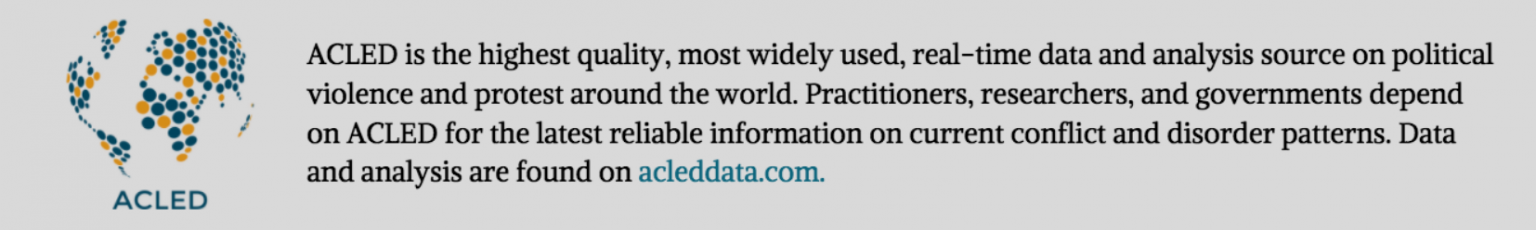

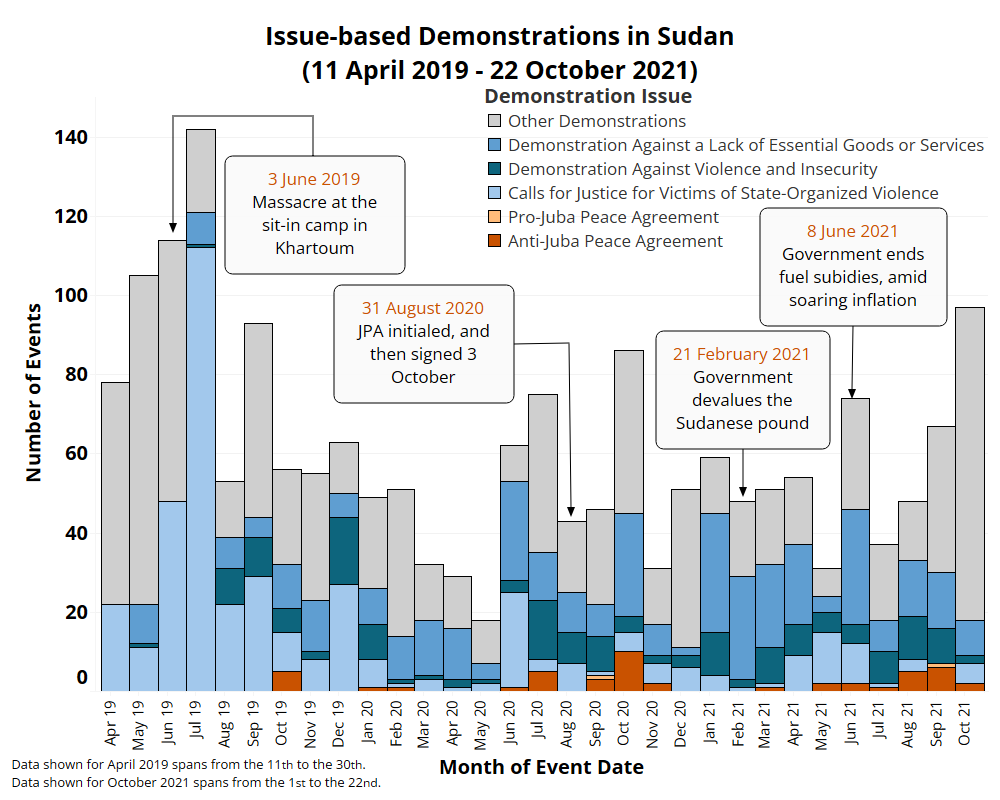

The consequence of this trajectory has been for growing disenchantment with the performance of the Transitional Government, as already strained living standards collapsed under the weight of soaring inflation and austerity. The figure below shows the primary issues that demonstrations were organized around, from the removal of Bashir to present:

Growing discontent with spreading insecurity and economic turmoil — alongside outrage at unaddressed grievances relating to attacks and massacres linked to state forces — has encouraged a shift in the political orientation of demonstrations in the country from mid-2020 onwards.2Note that initial demonstrations denouncing the performance of the Transitional Government in January and February 2020 focused on delays in replacing military governors with civilian ones, rather than on grievances relating to economic decline, justice, or insecurity. While explicitly anti-revolutionary demonstrations (mainly involving small numbers of NCP supporters demonstrating in Khartoum and some provincial towns, typically calling for a return to military rule and end to legal proceedings against NCP elites) continue to be low, infrequent, and poorly attended (Ayin Network, 21 October 2020; Radio Dabanga, 1 May 2020), anger at the performance of the FFC elites in office has been increasing among pro-revolutionary demonstrators. These groups (and particularly demonstrators connected to more radical Resistance Committees3Resistance Committees are local networks of activists responsible for organizing the majority of demonstrations in Sudan. They were first established during anti-government demonstrations in 2013. In practice, individual Resistance Committees tend to reflect the class composition of the neighborhoods they hail from (El Gizouli, 2019). and trade unionists) have increasingly demonstrated against both the military and civilian components of the Transitional Government, as shown in the figure below. As time has progressed, calls by demonstrators for justice have either been conjoined with or in some cases replaced by calls for the provision of essential goods and services.

This divergence reflects pre-existing rifts among the various components of the FFC, and particularly between more radical and politically independent youth and establishment political parties which purport to represent economic interests in their home regions. While pro-FFC demonstrations have continued, the pro- and anti-FFC camps have only come together to demonstrate against the common threat of military rule. This can be seen in the aftermath of an apparent attempt on the life of Prime Minister Hamdok in March 2020, and especially in September and October 2021 as the threat of a military takeover loomed large.

It was in this context of growing disenchantment and unrest in Eastern Sudan (discussed below) that the military had begun to make its move against the FFC civilian politicians with whom they were sharing power. The coup was a blunt instrument designed to neutralize faltering efforts being made by FFC elites to defang the leadership of the military bloc, and to keep the military as the dominant force in the Sovereign Council amid a brewing dispute over when the FFC would take control over the leadership of the Sovereign Council from Burhan. The military had been permitted to retain its leadership of the executive body for longer than the 21 months originally stipulated in an agreement outlining the terms of power-sharing that was signed in July 2019 (available here), as the JPA reset the starting date of the transitional period to October 2020 (UNSC, 2020: 1). There was increasing disquiet among civilian actors over the length of military leadership, which would now come to an end in July 2022 thanks to the JPA, which had been primarily negotiated between the military and rebels. Frustration at this power grab and with the prospect of further military leadership by the Sovereign Council has found its expression in calls to hand over power to the civilian branch of the government in November.

There were other imperatives for the army to seize power: there was ongoing pressure by many activists to prosecute senior military elites (including Burhan and Hemedti) for atrocities they are alleged to have perpetrated. Furthermore, the economic power of SAF has long been linked to a number of military-owned and military-operated businesses, and there have been increasing calls (including from Prime Minister Hamdok) for these assets to be appropriated by the state (Africa Confidential, 26 October 2021).

The coup was unimaginative in its planning, with the final seizure of power cruder than might once have been expected from the higher echelons of Sudan’s security cabal. An earlier ‘coup’ attempt on 21 September (supposedly conducted by allies of ex-President Bashir) was thwarted with suspicious ease (Tucker, 2021), and sparked a war of words between the military and the FFC, with each accusing the other of jeopardizing Sudan’s revolution. Meanwhile, unrest in Eastern Sudan compounded Sudan’s economic woes through preventing goods from leaving Port Sudan, with timing that raised suspicions of military involvement or support for the blockade.

An equally suspect pro-military demonstration calling for the dissolution of the civilian branch of the government began outside the Presidential Palace on 16 October. This called for the “expansion” of the Transitional Government to include members of a new faction of the FFC which recently broke away from the mainstream FFC faction (Radio Dabanga, 18 October 2021). This pro-military splinter faction comprised two Darfurian signatories of the JPA (the Minni Minnawi faction of the Sudan Liberation Movement/Army (SLM/A) and the Justice and Equality Movement, JEM) and several minor political parties which had previously been aligned (on paper, if not in practice) to the rump FFC.4Many rebel groups were attached to the FFC during its formative stages in early 2019, though most have been politically estranged from the FFC since negotiations between the TMC and FFC got underway in mid-2019. Minnawi and his entourage attended the demonstration designed to increase the power of this new FFC faction,5In response to Minnawi’s prominent role in the pro-military protests, demonstrators attempted to storm his house in Omdurman (Al Rakoba, 20 October 2021). as rumors and video footage emerged indicating that logistical and financial support for the pro-military demonstration was coming from leading figures in the military bloc.

Both JEM and SLM/A Minnawi have astutely used the JPA to reverse their fade into national irrelevance, with JEM leader Gibril Ibrahim becoming Minister of Finance under the patronage of Burhan, and Minnawi becoming Governor of Darfur with Hemedti’s backing (Africa Confidential, 26 October 2021).6Minnawi was installed as Governor of Darfur in August following his appointment in April. This has essentially created a parallel administrative system in Darfur, as the existing governors of the five states of Darfur remained in place. This was a result of Minnawi insisting the timetable for his appointment be accelerated, even if this meant his appointment got ahead of the schedule for the administrative reorganization of Darfur under the JPA implementation process. The military bloc could comfortably support an increase in the power of this splinter faction of the FFC, since the rebel groups leading it were dependent upon their SAF and RSF patrons for much of their power. Furthermore the new pro-military FFC faction could be passed off as a counterpart to the civilian bloc if one chose not to look too hard, which would be convenient in the event that the military undertook a ‘soft coup’ to substitute senior officials from the original FFC grouping for their pro-military counterparts.7The rebels had previously attempted to grab power and consecrate their partnership with the military by pushing for the controversial Transition Partners Council in December 2020, though the army was forced to walk back from these proposals following intense opposition from the FFC (Africa Confidential, 17 December 2020).

The pro-military sit-in protest was dwarfed by huge rallies organized in opposition to the threat of a military coup on 21 October, with hundreds of thousands of demonstrators taking to the streets in urban locations across Sudan. A flurry of diplomatic activity surrounded these events, including a visit from Jeffrey Feltman (the US Envoy to the Horn of Africa) to Khartoum. This is a visit which will surely come under increasing scrutiny, as details emerge questioning the decision by Feltman to leave Sudan after being told by Hemedti and Burhan “that they intended to seize power, citing a litany of failings by Sudan’s civilian leadership, according to a diplomatic source familiar with the exchange” (Foreign Policy, 26 October 2021). Shortly after Feltman departed Sudan, apparently under the belief that a crisis had been averted, the military and RSF moved against the mainstream FFC faction which was vying to take over control of Sudan’s Sovereign Council.

The large anti-military demonstrations of 21 October and the heightened external interest in Sudan might have prompted the military to reconsider the timing or scope of the coup, yet it appeared as though its protagonists were keeping to a pre-set schedule, one which had not been adjusted to take into account these very large and very high-profile demonstrations just days before. Within a few hours of the arrests of Hamdok and other senior FFC elites, demonstrators had taken to the streets of the three cities of greater Khartoum and parts of El Gezira state (likely Wad Medani, and possibly elsewhere) (Radio Dabanga, 25 October 2021b), and the Sudanese Professional’s Association (which had spearheaded the uprising against Bashir) called for a general strike and mass mobilization against the military (The Guardian, 25 October 2021). Demonstrations then spread to various towns and cities in Sudan, with reports emerging of demonstrations in Atbara, El Obeid, Zalingei, Nyala, Port Sudan, Kosti, Dongola, Ed Damer, Ed Duweim, and Wadi Halfa. Arrests of civil society members have also been reported in Nyala and in East Darfur (Darfur 24, 26 October 2021; Darfur 24, 28 October 2021), in addition to the crackdown underway in Khartoum.

If the objective of the coup was to enhance the military’s power, then this gamble has not guaranteed the desired result. The army could have undertaken a more low-key and gradual process of solidifying its existing grip on Sudan’s political economy, while continuing to extract further concessions from civilian forces in negotiations during politically fraught moments of its own making. Indeed, this may well have been the initial plan, until Hamdok refused to accept the demands of the army to reconstitute his cabinet in their favor (Reuters, 28 October 2021).

All signs indicate that the coup of 25 October has left the army politically exposed, and has ratcheted up the risk of mass violence in parts of the country. In seizing power so brazenly, Burhan may have overplayed his hand, and in the process has risked unleashing forces he is not fully in control of. In the following sections, the implications of the coup for Sudan’s margins will be explored. The coup has every potential to instigate renewed instability, through inducing power realignments in politically tense areas in the east and west of Sudan.

Eastern Sudan: Manufacturing Dissent

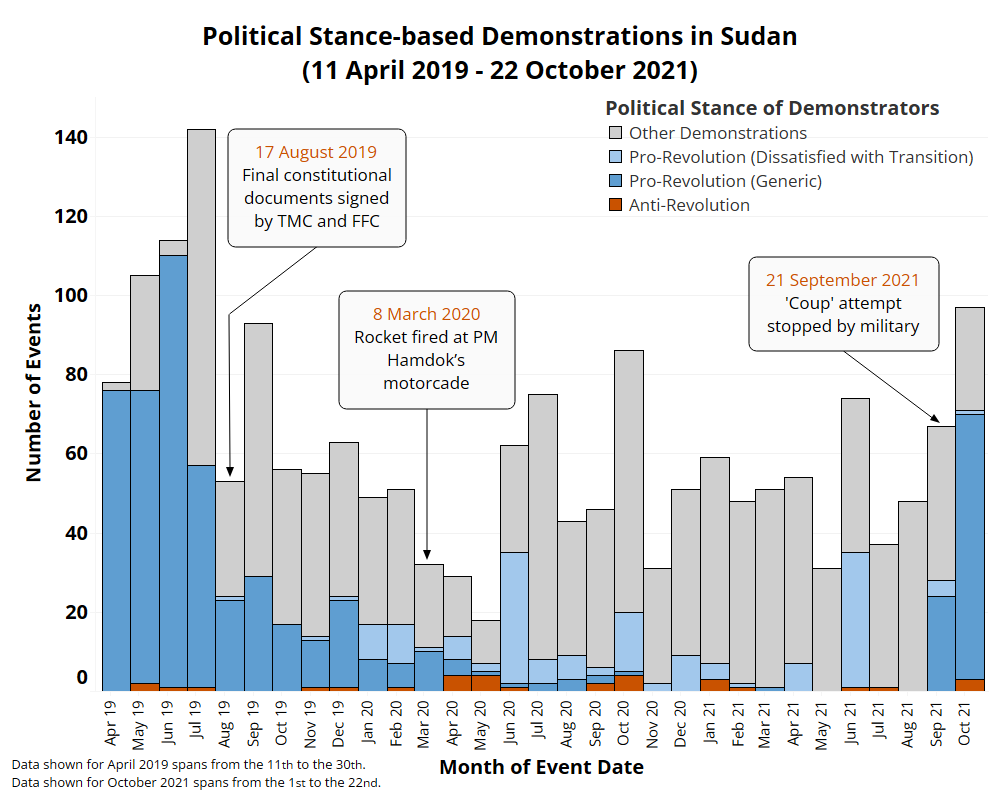

Developments in Eastern Sudan have become increasingly central to the politics of Sudan’s ‘transition,’ and reflect the power of agreements negotiated between the FFC and the TMC — and between rebel groups and the Transitional Government — to restructure local politics in ways which encourage violence and political toxicity. The turmoil in Eastern Sudan (often involving elements of the Beja, Nuba, and Beni Amir groups, with the specific trajectory of violence detailed in Danse Macabre) derives from the long-standing structural exclusion of the region and the more recent scramble by elites to secure influence in the post-Bashir context.8Eastern Sudan is poorly represented in the literature on Sudan’s peripheries. However, good accounts detailing various aspects of the recent political, social, and military history of the area can be found in International Crisis Group, 2013; Baas, 2013; Pantuliano, 2014; and Small Arms Survey, 2015. An excellent overview of the dynamics surrounding the JPA in Eastern Sudan can be found in section five of Gallopin et al. 2021. The discussion in this section draws from each of these sources. The political and economic fortunes of the region declined during recent decades, which have seen power become further centralized in Khartoum. The partial unravelling of central power since the fall of Bashir in 2019 — and the opportunities presented by the JPA for outsiders to expand their influence within the disparate regions of Sudan — has increased the risks of violent power struggles in several areas of Sudan, and especially in the East.

The focal point for the tensions in the region has become the (suspended) Eastern Track of the JPA, as well as control of the governorships of Kassala and Red Sea states. Struggles between a small number of contending elites to secure the opportunities presented by the allocation of senior positions has been refracted through rapidly escalating ethnic chauvinism, driving violence and political polarization in parts of the region.9Gedaref state has been relatively insulated from these dynamics, though the conflict in the disputed Fashaga has elements of the intersection of elite agendas with notions of ethnic belonging that have driven violence in Kassala and Red Sea states. At the core of this power struggle is Sayed Tirik, the nazir of the Hadendowa clan of the Beja ethnic group, and self-appointed head of the ‘High Council of the Beja Nazarat’ (see Gallopin et al.: 30).

Obtaining power in Eastern Sudan has long meant positioning oneself as an interlocutor between the government in Khartoum and the traditional tribal structures and interest groups of the East. The overthrow of the Bashir regime and the reordering of political influence portended by the JPA threatened to dislodge the sitting power-brokers from Eastern Sudan (including Sayed Tirik, as well as leaders of rebel groups who signed a 2006 peace agreement with Khartoum), who had maintained a strategically close relationship with the ruling NCP. The dismantlement of the NCP after April 2019 left these elites without a strong connection to the factions busily negotiating power in Khartoum, and worse still, their close association with a discredited Bashir regime risked making them outcasts in the new political dispensation.

Things looked better for those leaders of Eastern Sudan’s minor rebel groups who had parted ways with Bashir after the 2006 peace deal. The JPA proved to be a windfall for these groups: despite their inconsequential military capacity and tenuous claims to represent Eastern Sudan as a whole, they remained members of the Sudan Revolutionary Front (SRF, an unwieldy alliance of rebel groups and political dissidents founded in 2011). This status enabled them to push for an Eastern Track during peace negotiations between the SRF and the military branch of the Transitional Government taking place in Juba, and then negotiate with the military under this Track to secure senior positions and resources. Meanwhile, the FFC eventually obtained powers to appoint senior officials — including governors — who would almost certainly be drawn from anti-NCP ranks.10It later transpired that Dr. Suleiman Ali Muhammad Musa, the FCC-appointed governor of Gedaref state, had been previously aligned to the NCP. He was then fired from his position (Al Taghyeer, 18 August 2021).

As Gallopin et al. (2021: 29-31) explain, Tirik and his allies Musa Mohammed Ahmed and Sayyid Ali Abu Amna set about re-engineering and re-framing Eastern Sudanese politics around issues of ethnicity and representation. This was in order to limit the chance of power being redirected towards rebels attached to the SRF and to the incoming political elites linked to the FFC, by changing the terms of debate and the terms of inclusion in that debate. This helped Tirik to gain entry to negotiations that he would otherwise be shut out of, and to shift the basis of his claims for authority away from his politically toxic association with Bashir and towards his ethnic constituency.

This objective has been realized through two relatively simple steps. First, in order to marginalize Al-Amin Daoud (a rival from the Beni Amir group), Tirik and his companions whipped up anti-Beni Amir sentiment, exaggerating their historical connections to Eritrea to present them as ‘foreigners’ who have sought to usurp power from the original inhabitants of the state with the connivance of the NCP. Second, they established the ‘High Council of the Beja Nazarat’ to outmaneuver rivals from other Beja clans, and to give the illusion of the trio as speaking on behalf of the Beja ethnic group as a whole. The reality was somewhat different: “out of seven Beja nazirs, only Tirik joined the Council. The six other nazirs rejected the initiative” (Gallopin et al., 2021: 30).

From this platform, Tirik could agitate for violence between the Beja (often from his own Hadendowa clan) and the Beni Amir during critical political junctures (namely the appointment of governors, and progress in Eastern Track negotiations), while presenting himself to authorities as the sole conduit to all of the Beja clans, equating his own interests with that of a much larger ethnic constituency.

The consequence of this power game has been an escalation in violence and instability in urban areas of Eastern Sudan, accompanied by sustained anti-JPA protests which have been organized by Tirik’s ‘High Council’ (see map below). Each time an outbreak of ethnic violence occurs in cities such as Kassala or Port Sudan, Tirik has perversely attributed the violence to the Eastern Track of the JPA. Over time, this has created a self-fulfilling prophecy, in which calls for renegotiating or cancelling the Eastern Track are presented as the only solution to the crisis in the East. Yet Tirik and his allies would be the primary beneficiaries of such a renegotiation, and any renegotiation risks driving further violence fermented by Beni Amir and Beja elites, as the loser pushes for the status quo ante to be restored.

Serious violence broke out in Eastern Sudan (and especially in Kassala) during October 2020, when the government bowed to pressure from Tirik and fired the Beni Amir governor of Kassala state, Saleh Ammar. While tensions have persisted intermittently since this time, the situation in the East once more became a matter of national concern in the past month and a half. On 17 September 2021, supporters of Tirik established roadblocks in each of the states of Eastern Sudan, reducing the flow of essential goods from Port Sudan into the central area of Sudan (including Khartoum) while also threatening oil exports. The Port itself was occupied from 24 September. The demonstrators were calling for the Eastern Track of the JPA to be scrapped (Al-Monitor, 22 October 2021). There has been much speculation about the connections between the military and these demonstrations, given their overlap with the timing of the ‘coup’ attempt on 21 September (Musa, 2021). Suspicions were not allayed when, following the coup a month later, Sayed Tirik swiftly endorsed the new military government and announced plans to relax the blockade (Sudan Akhbar, 25 October 2021; Radio Dabanga, 28 October 2021).

The stability of Eastern Sudan has been at the mercy of the power realignments wrought by the FFC-TMC negotiations of 2019 and the JPA of 2020. This is set to continue in the wake of the coup of 25 October, and may well worsen as a result of it. If the military is able to consolidate its gains from the coup, then this will in all likelihood tip the relationship between Khartoum and the contending elites in the East back in the favor of Tirik, given the apparent co-ordination between Tirik and the army. If the coup fails, then this leaves Tirik exposed and more isolated than before. In either scenario, there is every chance that Tirik’s rivals will begin to play his game on their own terms, mobilizing their supporters to secure power in the name of resisting the recent encroachment by the military.

Darfur and the Two Areas after the JPA

The most serious ripple effects from the coup are likely to be felt above all in Sudan’s war-scarred peripheries to the south and west. ACLED’s previous report on these areas — Riders on the Storm — focused on the risks posed by the JPA to security in the Two Areas (the Nuba mountains of South Kordofan, and Blue Nile state) and especially to Darfur. That report also argued that the JPA would consolidate an unstable and reactionary alliance between the army, the RSF, and the rebel groups who signed the peace agreement, further tipping the balance of power further in favor of the military bloc. Meanwhile, ACLED’s report on cross-border violence in the Horn of Africa — Red Lines — emphasized the risks such violence poses to the borderlands between Sudan and Chad and between Sudan and South Sudan in the event of a breakdown of order at the national-level.

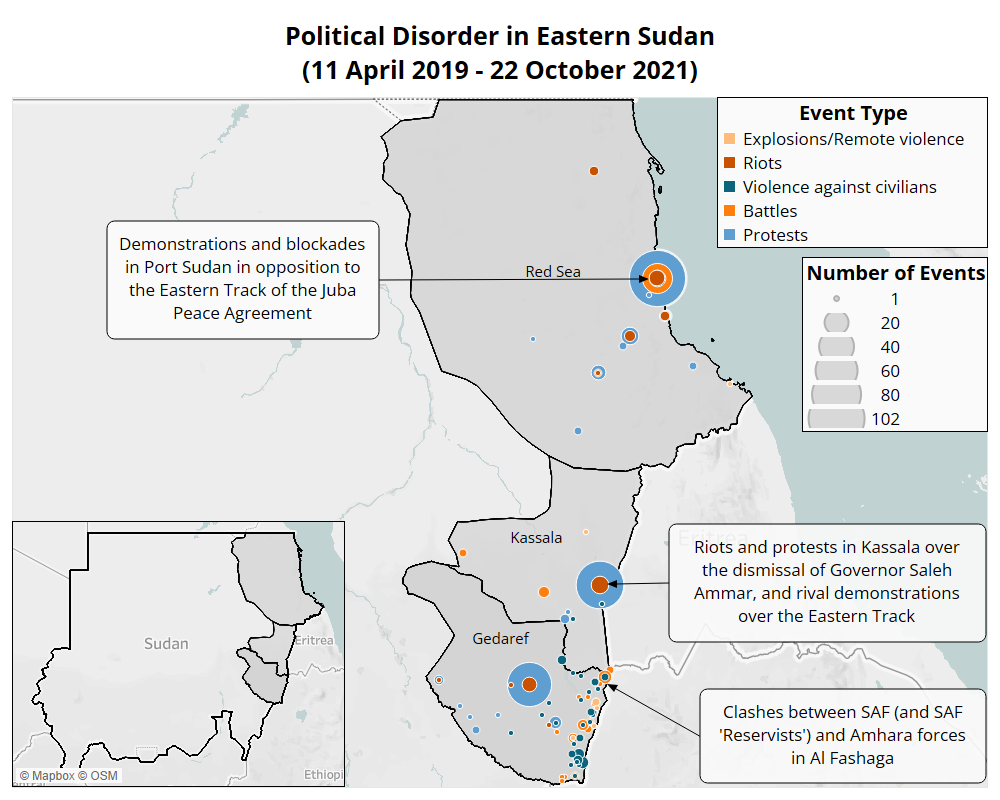

All signs indicate that the JPA has done nothing to rectify tensions and violence in Darfur, even if violence has flatlined in South Kordofan, thanks in part to the ongoing ceasefire in the area by a rebel group who refused to sign the JPA. In addition to ongoing violence in Darfur, demonstrations denouncing insecurity and conflicts continue in much of the central belt of Darfur. As Tiziana Corda (2021) shows, violence has continued to escalate (albeit sporadically) in Darfur since the signing of the JPA. Events in Darfur have continued along similar lines to pre-JPA violence, which included increasingly urbanized violence involving contending ethnic militias (with Arab-identifying militias frequently being supported by RSF paramilitaries) amid chronic insecurity around areas with a high concentration of internally displaced persons (IDPs). Much of the fighting involving irregular militias continues to be lopsided, with non-Arab groups the subject of serious reprisal attacks by large numbers of Arab-identifying militias whenever a non-Arab group is implicated in criminal harm inflicted on members of an Arab group.

ACLED data show that the epicenter for the violence in Darfur has continued to shift towards West Darfur state (see map below). Here the mass violence in El Geneina city which began in late December 2019 was reignited from 16-19 January 2021 and again from 3-6 April 2021. This pitted Rizeigat militiamen against members of the Masalit ethnic group, who were able to summon the assistance of Masalit militias from surrounding areas. During the fighting in January (which led to 163 reported deaths and wounded 215), militias from Chad were reported to be involved in the violence, while RSF paramilitaries were reported to have been fighting alongside the Rizeigat in April (which led to 147 reported deaths and at least 233 wounded). Both bursts of violence witnessed the torching of Masalit neighborhoods and IDP camps in and around El Geneina.

In South Darfur state, escalating violence involving Fellata (a.k.a. Fulani) pastoralists broke out between October 2020 and June 2021, including clashes with Rizeigat pastoralists as well as the Taaisha and Masalit groups. In several cases, Sudanese security forces were involved in the fighting against the Fellata, with the death tolls climbing significantly whenever government forces became entangled. Particularly serious clashes took place in Tulus locality between Fellata and Rizeigat pastoralists (with the latter allegedly backed by the RSF) on 18 January, after a child from the Rizeigat was murdered the day before, leading to the reported deaths of 72 people and wounding 73. Meanwhile, between 35 and 42 people were reportedly killed and almost 50 wounded in a retaliatory attack by Fellata militia in Um Dafoug locality, with SAF and RSF personnel supporting Taaisha militia.

Jebel Marra in Central Darfur state has continued to experience recurrent infighting between elements of the fractious SLM/A al Nur rebellion (which did not sign the JPA), and clashes between the holdout group and government-aligned forces. The result of this has been for fatalities from events involving the SLM/A al Nur to be at their highest levels since mid-2018, with mass displacement typically following in the wake of activity by the group. While some of the clashes involving the group relate to disputes over land or gold mines,11This includes clashes among unspecified factions of the group (possibly involving the RSF) on 12 May 2021 in Fanga Suk over land, as well as fighting between the SLM and Beni Hussein militia in Kas locality over gold mines the following month, which reportedly killed 14 people. there is only limited information on most other events. Most internal clashes involved fighting between loyalist units and splinter groups commanded by Mubarak Aldouk, Sadiq al-Fakka, and Zunoon Abdelshafi (with the latter reportedly supported by RSF soldiers). Notable incidents include clashes in mid-July 2021 involving Sadiq al-Fakka’s forces (possibly backed by government troops) at Sortony IDP camp in Kebkabiya locality, which led to the deaths of around 17 people, most of whom were likely to be IDPs. Heavy fighting between the SLM/A al Nur and an unspecified pro-government militia (backed by SAF Military Intelligence) were also reported in Tawila and North Jebel Marra localities in late January and early February of this year, with unverified reports putting the death toll at 77 across several days of fighting.

The increasing violence in much of Darfur would indicate that the JPA has done nothing to improve the complex situation in the region, and may even have aggravated it. In 2021, there has also been an increase in violence in some urban areas of Darfur, as minor rebel groups who signed the JPA have attempted to corner criminal markets ( Darfur 24, 28 July 2021; Darfur 24, 30 July 2021). The extent of this criminal activity is presently unclear. In early April clashes were also reported between an unspecified signatory to the agreement and the RSF close to the border with Chad west of El Geneina, wounding five RSF paramilitaries.

The only instance in which a JPA signatory has inserted itself into ethnicized violence took place on 6 August 2021, and this did not go in the groups favor. This followed sustained violence in parts of eastern Tawila and western Dar As Salam localities (in North Darfur state) led by the Shotia sub-clan of the Mahamid Rizeigat, and involved a series of attacks against Zaghawa IDPs who had been resettled in the area, re-displacing hundreds. Rebels from the small Sudan Liberation Forces Alliance operating alongside SAF and RSF soldiers were ambushed by the Shotia militia near the village Kolgi while attempting to restore order, with between 10 and 20 soldiers of the force being killed (UNSC, 2021: 4).

Since the coup of 25 October, there has been increasing concern that violence will intensify in areas occupied by both rebels loyal to the mercurial Abdul Wahid al Nur in central Darfur, and to the Abdelaziz al Hilu faction of the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-North (SPLM-N) based in parts of South Kordofan and Blue Nile states (with the Blue Nile branch of the SPLM-N Abdelaziz faction under the command of Abdelaziz’s powerful deputy, Joseph Tuka). The coup was condemned by both of these holdout groups (Radio Dabanga, 27 October 2021), after having been welcomed by most of the rebel groups who signed the JPA.12There is ambiguity regarding the position of the much weaker Malik Agar faction of the SPLM-N (which also signed the JPA) in relation to the military bloc and to the coup. In the run-up to the coup, one senior member of the group positioned themselves against further military control (Sudan Tribune, 23 October 2021), whilst another aligned with the military bloc (Al Jazeera, 18 October 2021). Two days after the coup, Malik Agar came out against the coup (Voice of America, 27 October 2021).

In the event of further political turmoil in Khartoum, then there are indeed grounds to be worried about renewed conflict in these areas. However, it should be recognized that in the case of Darfur, government and pro-government forces appear to already be engaged in a proxy war with SLM/A al Nur rebels, utilizing splinter factions to chip away at the resource base of the core faction of the group. This existing conflict could nevertheless worsen, and might threaten to drag in the JEM and the SLM/A faction under Minni Minnawi against Abdul Wahid’s more powerful (but volatile) forces in central Darfur. JPA signatories have reportedly been recruiting heavily in Darfur in 2020 (International Crisis Group, 2021: 8-10), in order to increase their clout in the Transitional Government and in the branches of the security services into which they are integrated. This is not guaranteed to increase the military effectiveness of these groups, but problems with training and logistics might be eased were JEM and SLM/A Minnawi forces to operate alongside government soldiers and paramilitaries.

A more troubling scenario for Darfur would involve the merging of the rebel-government conflict with the intensive ethnicized violence which has been increasing in parts of Darfur. In such a scenario, sparks could quickly jump between military and ethnicized conflicts in several flashpoint areas. This would be further complicated in the event of a deterioration in relations between Western Sudanese military elites (of which Hemedti is the most powerful) and the Riverain military establishment (represented, at least for now, in the figure of Burhan). Any showdown between Hemedti and Burhan would also risk putting JEM and SLM/A Minnawi on different sides of a rift at the apex of power in Khartoum.

Finally, and with regards to SPLM-N Abdelaziz forces in the Two Areas, the military coup will at best significantly complicate the interminable peace negotiations between Abdelaziz and the government. The rebel leader has been distrustful of the military elites in the Transitional Government, and more ambitious than JPA signatories in his demands for sweeping political and military reforms in Sudan. While more materially-motivated rebel leaders might relish the opportunity presented by a misfired coup to press home their demands, it is reasonable to expect Abdelaziz to become more cautious in the event of either political fragmentation in Khartoum or the consolidation of power under the military. The relative peace in South Kordofan is a hostage to these negotiations, and a sudden deterioration in relations between the army, RSF, or SPLM-N Abdelaziz faction would have dramatic implications for the stability of the borderlands which link Sudan and South Sudan.

Conclusion

Dark clouds are on the horizon for Sudan. The coup d’état elevates the role of self-interested elites from the country’s fractious military bloc, and may well set the stage for a showdown between these forces. As Jean-Baptiste Gallopin (2020) presciently observed, “Since Hamdok’s appointment, the domestic balance of power has once again tilted in favor of the generals, who could seize on the climate of crisis to restore military rule. If they remove civilian leaders from the equation, rival factions within the military and security apparatus will be set on a collision course.” Serious tensions emerged between the leadership of the RSF and SAF in June of this year (Reuters, 22 June 2021), and there is every opportunity for those tensions to flourish in the post-coup environment.

The decision by Burhan to seize power would seem to be a reckless one, which is already showing signs of having backfired. If the military feels besieged and deems that they have little room for maneuver, then the potential for further violence against demonstrations and political opponents of the military counter-revolution will increase. If the military accedes to demands to reverse the coup (or partially reverse through enticing Hamdok to preside over a new cabinet, see Sudan Tribune, 29 October 2021), demonstrators, FFC elites, and international mediators will be confronted by a dilemma. Do they try to repair a dangerous power-sharing agreement which has brought no concrete benefits to most Sudanese, or should they take the alternative route of building a new political order without the military and civilian elites responsible for Sudan’s protracted crisis? International powers calling for the restoration of these power-sharing agreements (e.g. The White House, 28 October 2021) are likely to be met with scorn by protesters in Sudan, though may find an audience among the less principled members of the FFC political elite.

In the event that the military refuses to back down, it is possible that sanctions may be reinstated on Sudan, and that Western countries may call for the debt cancellation process (under the World Bank and International Monetary Fund’s Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) Initiative) to be suspended or even reversed. Although over $50 billion of Sudanese debt is scheduled to be lifted, the removal of this unpayable debt is contingent on Sudan passing through a three year process to reach the HIPC Completion Point (International Monetary Fund, 29 June 2021).

The international response to the coup has ranged from damning to cautious. South Sudan, Egypt, and Saudi Arabia — each of whom has a vested interest in keeping the military as the dominant force in Khartoum — have mostly refrained from condemnation, and have instead issued vague statements calling for continued dialogue (Eddie Thomas Twitter, 26 October 2021; Anadolu Agency, 26 October 2021). Despite close relations between the militaries of Sudan and Egypt, there have been suggestions that Cairo was caught unaware by the coup (Washington Post, 26 October 2021).

In recent years, the ruling elite of South Sudan have consistently behaved in a way which suggests they believe their interests are best served by aligning with whomever is currently in power in Khartoum, though an unexpected military coup in Khartoum will raise concerns in Juba about their military forces taking inspiration from their northern counterparts. Juba can be expected to push for any option which might bring about greater consensus and stability in Sudan, particularly given the effect national instability and instability in Eastern Sudan will have for their oil revenues (see Radio Tamazuj, 27 October 2021). However, this may put Juba in a difficult position if stability in Sudan is best attained through opposing an expansion in the power of the military.

There were many warning signs that Sudan’s ‘transition’ was unlikely to rectify the disintegration of Sudan’s economy or reverse the country’s entrenched militarism, which were highlighted in ACLED’s previous reports on Sudan. Developments since the fall of Bashir have tended to proceed along lines laid out in the agreements between the TMC and the FFC, and in the JPA. These agreements all but ensured that political and economic reforms would reflect the interests of the upper levels of political and military factions who were now ensconced in power, and risked setting these factions against one another. There is little reason to expect a different outcome if these agreements are restored.

Part of the author’s time was supported by the European Union’s Horizon H2020 European Research Council grant no: 726504