Papuan Independence and Political Disorder in Indonesia

5 October 2022

In Indonesia, political disorder in Papua and West Papua1West Papua and Papua provinces are referred to collectively in this report as Papua, representing the western half of the island of New Guinea. This report uses Papua when referring to the entire region and clarifies the particular province being discussed where necessary. In this report, Papua province is inclusive of the areas that will be divided into Central Papua, South Papua, and Highland Papua provinces. provinces increased in 2021 amid opposition to the revision of the Special Autonomy Law. First promulgated in 2001, the Special Autonomy Law was initially intended to give greater power to the local governments in the Papuan region. However, new revisions to the law introduced in 2021 expand the central government’s authority and have allowed for the unwelcome creation of new provinces in the region (Tempo, 16 July 2021). Tensions between the political demands of many Papuan groups and the centralized, development-oriented agenda of the Indonesian state continue to fuel unrest. This report examines disorder trends related to the issue of Papuan independence since 2018,2ACLED’s Indonesia dataset contains data from January 2015 to the present. This report examines events from 2018 to the present. For more on what users should keep in mind when using ACLED’s historical data (events coded prior to 2018), see Adding New Sources to ACLED Coverage. focusing in particular on the rise in clashes between state forces and the West Papua National Liberation Army (TPNPB), increasing levels of violence targeting civilians by the TPNPB, and disproportionate state intervention in peaceful protests held by Papuans and Papuan groups.3ACLED codes Papuan Ethnic Group (Indonesia) as an Associated Actor where the Papuan identity of individuals or a group was determined in the source reporting to be salient to the event. It is possible for some demonstrations to have included Papuans without being reported.

Key Trends

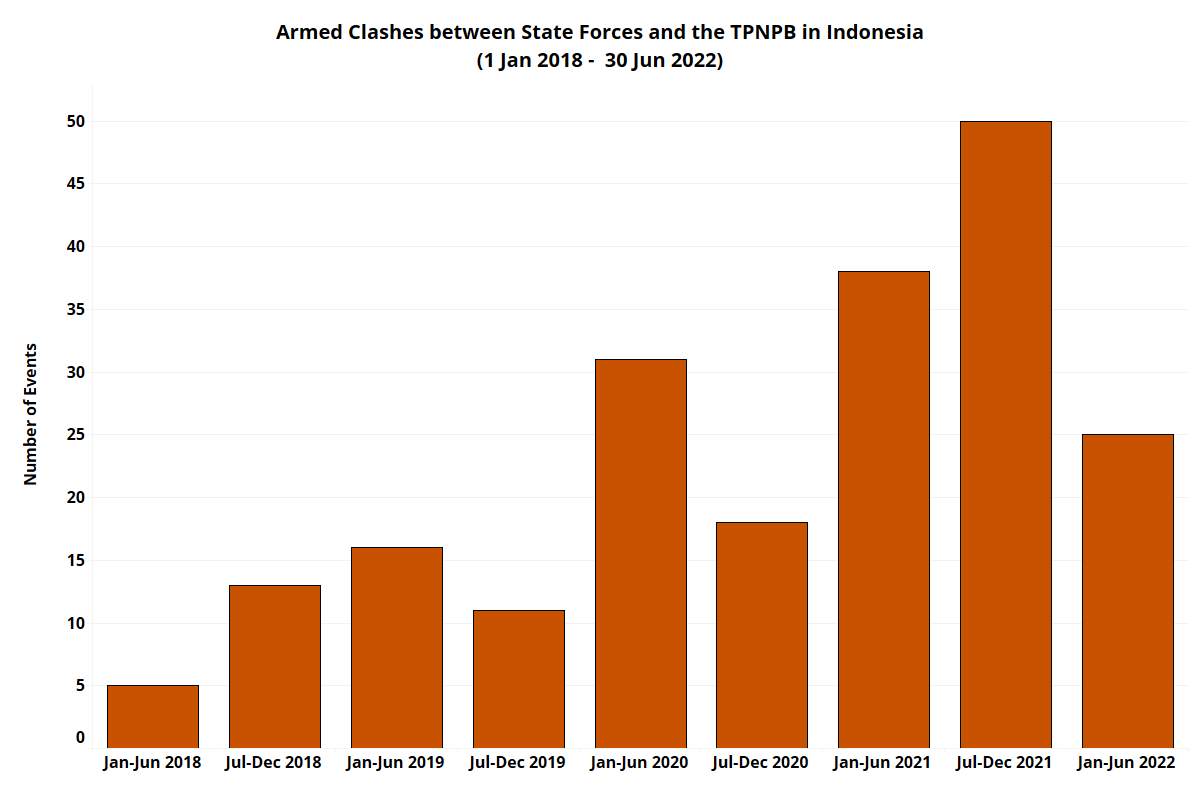

- Armed clashes between state forces and the TPNPB have risen since 2018. Clashes increased by nearly 80% in 2021 in comparison with 2020.4ACLED maintains a ‘living dataset,’ with data revised as more information becomes available about events. Restrictions on journalists and independent monitors in Papua means that tracking political disorder in the region is challenging. ACLED currently covers 14 sources for Indonesia weekly and continues to review its sourcing and coding to ensure the data match the situation on the ground to the extent that it is covered by journalists and other organizations. ACLED does not have a separate mechanism to independently verify events reported by the sources covered.

- Since 2018, armed clashes have spread geographically outside of the traditional TPNPB stronghold in the Black Triangle regencies of Puncak Jaya, Lanny Jaya, and Mimika (IPAC, 13 July 2022), with notable increases in the regencies of Intan Jaya, Puncak, and Yahukimo. Since the beginning of 2021, armed clashes between state forces and the TPNPB have been reported in over 20 new locations across the region where they had not previously been recorded in the ACLED dataset, which begins in 2015 for Indonesia.

- Violence targeting Papuan civilians by state forces and violence targeting civilians by the TPNPB have continued at high levels over the past two years, with a notable increase in TPNPB civilian targeting since 2020.

- Indonesian state security forces have dispersed or repressed peaceful protests featuring Papuans and Papuan groups more frequently than those not featuring Papuans and Papuan groups.

Historical Background

The conflict over Papua has its roots in the decolonization of Indonesia from the Netherlands. After Indonesia declared its independence on 17 August 1945, the Dutch government wanted to retain influence in the Netherlands New Guinea (present day Papua) and aimed to turn the region into a self-governing territory (IPAC, 24 August 2015). In 1961, the Dutch government formed the New Guinea Council to prepare Papuans for independence, which led to the raising of the Morning Star flag for the first time on 1 December of that year. The flag has since become the symbol of the Papuan independence movement.

The Indonesian government’s strong opposition to this development led to Indonesia and the Netherlands signing the New York Agreement in 1962 (HRW, February 2007). The agreement provided for the region’s authority to be transferred temporarily to the United Nations (UN), and later to the Indonesian government, during the planning of a self-determination referendum for Papua inhabitants.

Before the referendum, named the Act of Free Choice, was held, Indonesian state forces began to suppress political activists, with reports emerging of Papuan leaders being arrested or exiled (ICTJ, June 2012). The 1969 Act of Free Choice involved asking 1,022 Papuan representatives, handpicked by Jakarta, to vote on whether they wanted integration with Indonesia, rather than holding a one-person, one-vote referendum. The Indonesian authorities argued that the voting method used was appropriate given the challenging geographic terrain and the lack of political and social development in the region (HRW, February 2007). While the vote was unanimous in support of integration, it was subsequently dismissed by pro-independence Papuans as coerced.

As tensions over the issue of independence were escalating prior to the 1969 referendum, in April 1965, a group of Papuans clashed with Indonesian military personnel in Manokwari. This marked the first clash between a pro-Papua independence group and Indonesian forces. Eighteen soldiers and four pro-independence fighters died in the clash. Following the incident, Indonesian authorities launched an extensive military operation in Manokwari, burning villages and carrying out aerial attacks (ICTJ, June 2012).

This contributed to the emergence of the TPNPB, which is the military wing of the Free Papua Movement (OPM), an umbrella organization for the pro-Papua independence movement that proclaimed Papuan independence on 1 July 1971 (IPAC, 24 August 2015). Throughout the years, the TPNPB has pursued Papuan independence by engaging in armed clashes with Indonesian security forces and launching numerous deadly attacks within Papua. The TPNPB has historically not posed a significant threat to the state given its lack of a central command and coordinated strategy, as well as factionalism between the smaller groups that operate under the TPNPB name (IPAC, 24 August 2015). However, in recent years, the group has coalesced into a more united front under a 2018 declaration of “war” against the Indonesian state and obtained more weapons to allow for increased attacks on government forces (IPAC, 13 July 2022).

In April 2021, the Indonesian government formally designated the TPNPB as a “terrorist” organization after it killed the head of the State Intelligence Agency (BIN) in Papua province in Puncak regency (Tempo, 29 April 2021; CSIS, 7 July 2022). By labeling the group “terrorists,” the Indonesian government aims to block the TPNPB’s access to any potential funding in order to hamper its activities (CNN Indonesia, 29 April 2021). The TPNPB’s “terrorist” classification has been highly criticized by various organizations and public figures, including the governor of Papua province, who has urged the Indonesian government to review the label as it could be used by authorities to suppress Papuans peacefully calling for independence (Jubi, 30 April 2021).

Clashes Between State Forces and the TPNPB

Armed clashes between the TPNPB and state forces have been on the rise since 2018 (see figure below), when the TPNPB declared “war” on the Indonesian government (IPAC, 13 July 2022). At the same time, the government has deployed a growing number of armed forces to the region. These troop deployments increased further after unrest broke out in August 2019 over racial taunts of Papuan students (Asia Times, 23 August 2019). The total number of state forces deployed in the region remains classified, though Papua and West Papua provinces are known to have the largest presence of Indonesian troops in the country (Walhi, 12 August 2021).

The size of the TPNPB is difficult to estimate, as various smaller groups with different leaders operate under the TPNPB banner (IPAC, 24 August 2015). The fragmentation of the group also contributes to difficulties establishing dialogue with the government (Detik, 3 December 2020). The group is believed to partly finance its activities through illegal mining in Intan Jaya, Paniai, Timika, and Yahukimo regencies (Kompas, 9 April 2021).

The TPNPB has moved from using rudimentary weapons to a growing supply of firearms, with police forces claiming that the TPNPB had purchased guns from dealers in Ambon, Papua New Guinea, and indirectly from the Philippines (Tribunnews, 23 May 2022). On several occasions, members of state forces have been arrested for their involvement in gun trading with the TPNPB (Kompas, 24 February 2021). The increased supply of weapons has translated into more sustained battles as opposed to the hit-and-run incidents more often reported in the past (IPAC, 13 July 2022).

In recent years, drawing on its increased weaponry and organization to carry out attacks across the region, the TPNPB has expanded its area of operations outside of its traditional stronghold of the Black Triangle regencies of Puncak Jaya, Lanny Jaya, and Mimika (IPAC, 13 July 2022), with notable increases in clashes in the regencies of Intan Jaya, Puncak, and Yahukimo (see figure below). Since the beginning of 2021, armed clashes have been reported in over 20 new locations where they had not previously been recorded in the ACLED dataset, which begins in 2015. These new locations include areas in regencies and districts where the TPNPB had not operated for many years (IPAC, 13 July 2022).

Violence Targeting Civilians

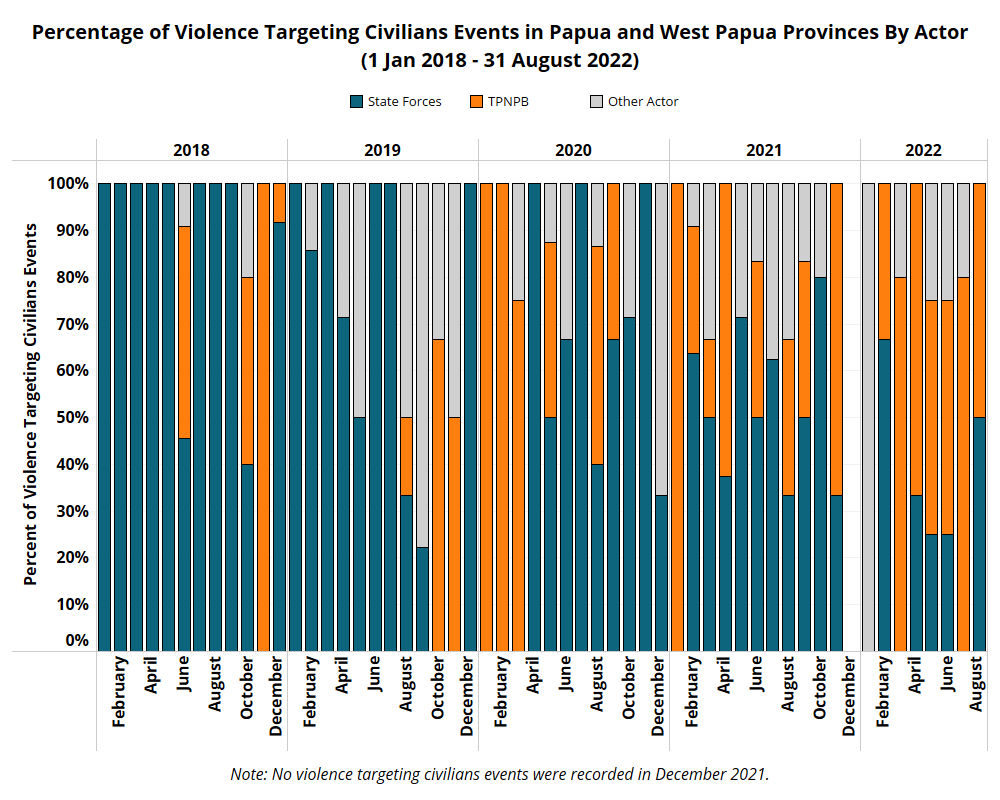

Civilians have borne the brunt of the recent escalation of the conflict between state forces and the TPNPB. Between 60,000 and 100,000 Papuans have been displaced in the region since late 2018 due to the unrest (OHCHR, 1 March 2022). Civilians have been caught in the crossfire of clashes between state and TPNPB forces, and also directly targeted by both actors. Violence targeting civilians has been perpetrated by the state against Papuans – both in Papua and outside – accused of supporting the TPNPB, while the TPNPB has targeted civilians perceived to be affiliated with the government in an effort to disrupt transmigration and development projects in the region. Civilian targeting by the TPNPB has been contained within Papua. While a greater percentage of violence targeting civilians in Papua and West Papua provinces has been carried out by state forces in recent years, the percentage of violence targeting civilians by the TPNPB has increased notably in 2022 (see figure below).

State Violence Targeting Papuans

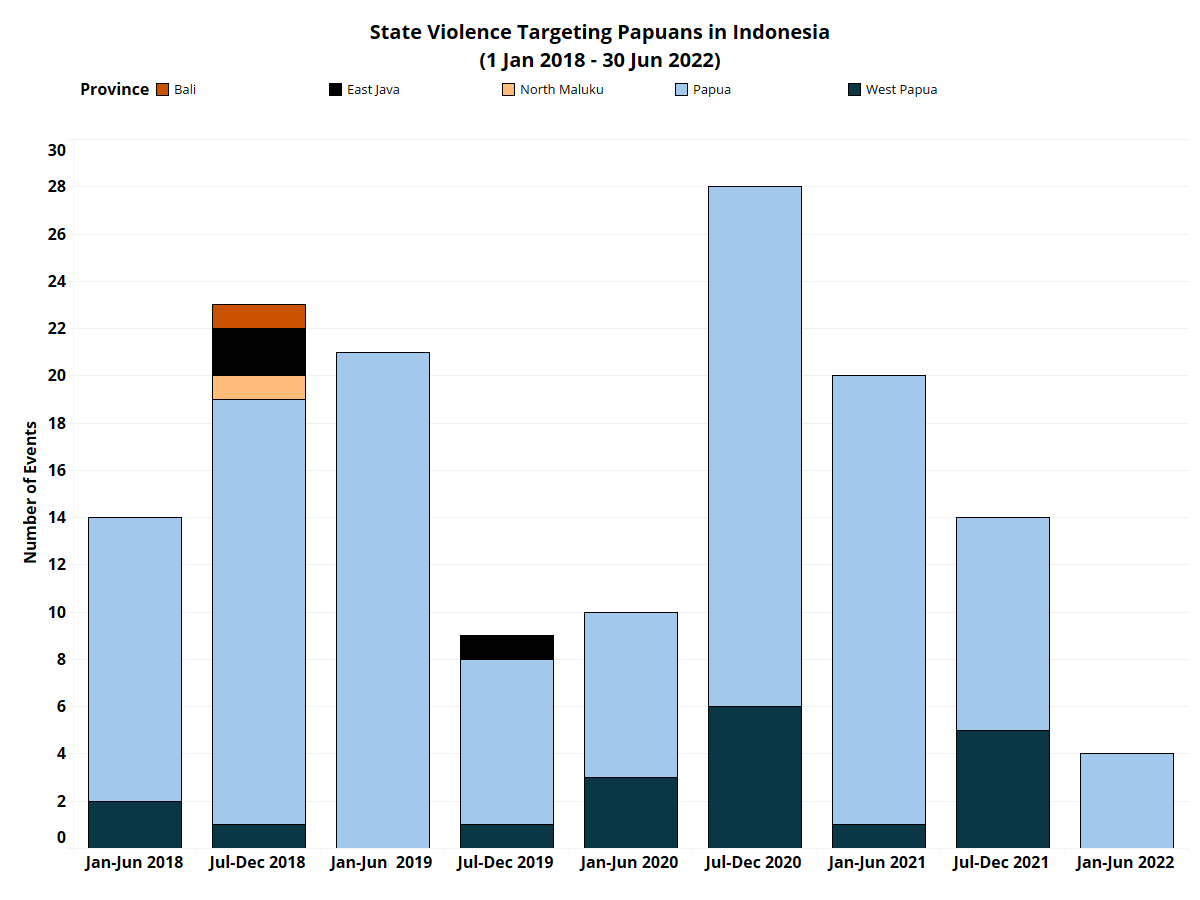

There is a long record of human rights abuses by the Indonesian government in the region (UN, 1 March 2022). Recently, independent experts at the UN expressed concern over torture, enforced disappearances, and extrajudicial killings of Papuans by security forces (OHCHR, 1 March 2022). The Indonesian government denied the abuses and claimed the UN was biased (The Diplomat, 3 March 2022). Papuans outside of the region have also been targeted by state forces. ACLED records the highest levels of violence targeting Papuan civilians by state forces across Indonesia in 2020, with attacks continuing at elevated levels in 2021 (see figure below).

Much of this violence has been framed by the government as the result of operations targeting TPNPB members or people who have links to the group. The claims denying the indiscriminate targeting of civilians are often made without providing strong evidence (Suara Papua, 13 April 2022). On 22 August 2022, four Papuans were killed and mutilated in Mimika Baru district, Papua province and discovered by locals four days later in a river near Timika town; the authorities claimed the four were seeking weapons which their families denied. Six soldiers have been arrested for their involvement in the case (HRW, 2 September 2022).

As well, the increased presence of the military in Papua contributes to targeting of civilians, including children. For example, on 22 February 2022, Indonesian forces assaulted seven Papuan children at a military post in Puncak regency, claiming without proof that the children had stolen a gun from the post earlier that day. One of the children later died in the hospital (Jubi, 2 March 2022). On 5 April 2022, the Indonesian military forces shot dead a Papuan teenager in Nduga regency during military operations against the TPNPB (Suara Papua, 13 April 2022).

Military air raids have also resulted in civilian casualties. In October 2021, Indonesian security forces dropped explosives from the air in four villages in Pegunungan Bintang regency. Civilian houses, most likely belonging to ethnic Papuans, caught on fire due to the attack (Jubi, 25 October 2021).

Additionally, the UNHCR has expressed concern over police violence against Papuan civilians (UNHCR, 21 February 2019), who frequently face violence when arrested and while in detention (Tapol, April 2013; Human Rights Papua, 30 December 2021). This led to a campaign in 2020 called ‘Papuan Lives Matter’ mirroring the ‘Black Lives Matter’ movement that started in the United States (Foreign Policy, 16 June 2020).

TPNPB Violence Targeting Civilians

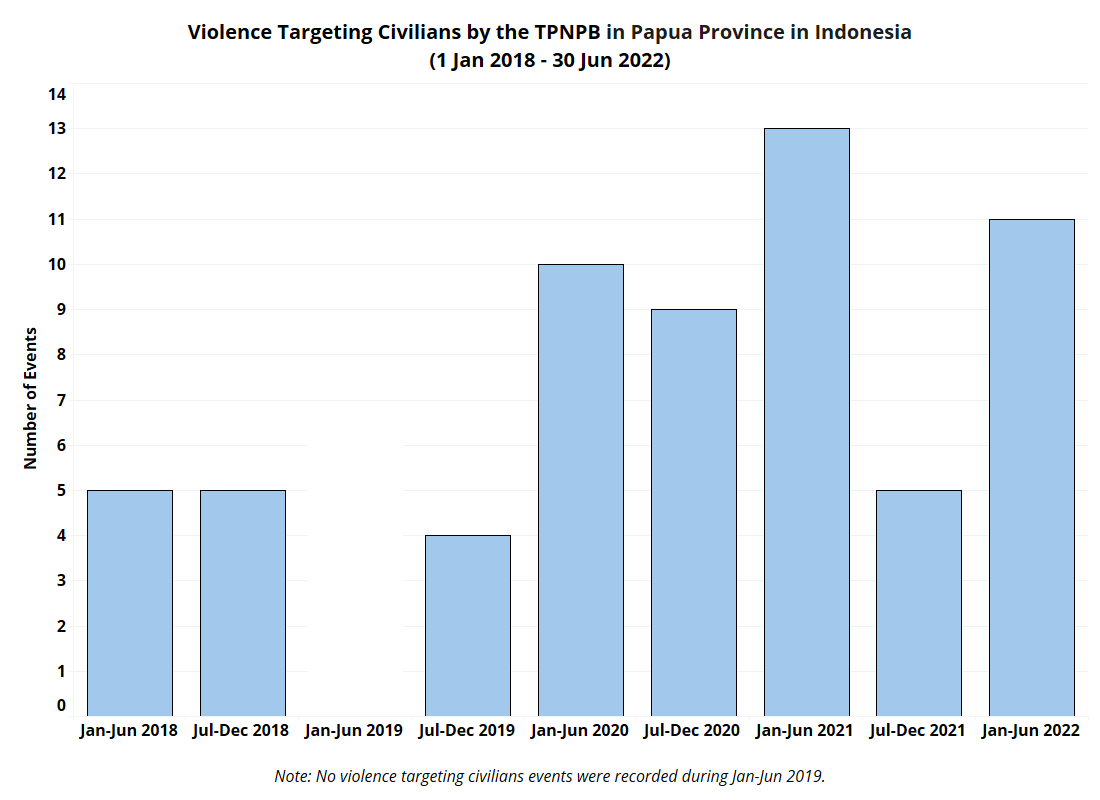

There has been a marked increase in civilian targeting by the TPNPB in the last two years (see figure below). In an effort to hinder the central government’s development and infrastructure projects, the TPNPB has carried out attacks against workers contracted to government projects and non-Papuan migrants who have settled in the region. Targeted civilians include construction workers, miners, motorbike taxi drivers, teachers, and health workers. In one of the deadliest attacks on civilians, in December 2018, the TPNPB killed multiple non-Papuan migrant laborers working on the Trans-Papua Highway, a project sponsored by the central authorities.

Papuan leaders of other organizations have vocally opposed the targeting of civilians by the TPNPB (Suara Papua, 27 August 2021; CNN Indonesia, 6 March 2022). The TPNPB often claims those targeted are spies for the Indonesian government, though frequently without sufficient proof (Tirto, 4 March 2022). Some teachers and health workers have been targeted for allegedly being informers. For example, in April 2021, two teachers were killed by TPNPB forces in Puncak regency after they were accused of being spies for the Indonesian government. The government paid a ransom to be able to land a plane and evacuate the bodies (Kompas, 12 April 2021).

In addition to labor groups associated with the state, the TPNPB has also targeted non-Papuan migrants in the region (Republika, 8 June 2021). The number of settlers in Papua has increased significantly in recent years, now comprising over half the population (Tempo, 28 November 2019). The continuing migration of non-Papuans into the provinces is seen by the TPNPB as encroaching on Indigenous land and shifting the demographics to disfavor those who call for independence (Suara Papua, 15 December 2017). In one such attack, on 16 July 2022, the TPNPB fired shots at a truck carrying non-Papuan civilians in front of a shop in Nduga regency. They also attacked the civilians with sharp weapons. Eleven people died, and two others were wounded. According to police, the group launched the attack after a villager recorded a video of TPNPB members raising the Morning Star flag (Jubi, 18 July 2022, Kompas, 21 July 2022).

Demonstrations Featuring Papuans and Papuan Groups Met with Greater Intervention

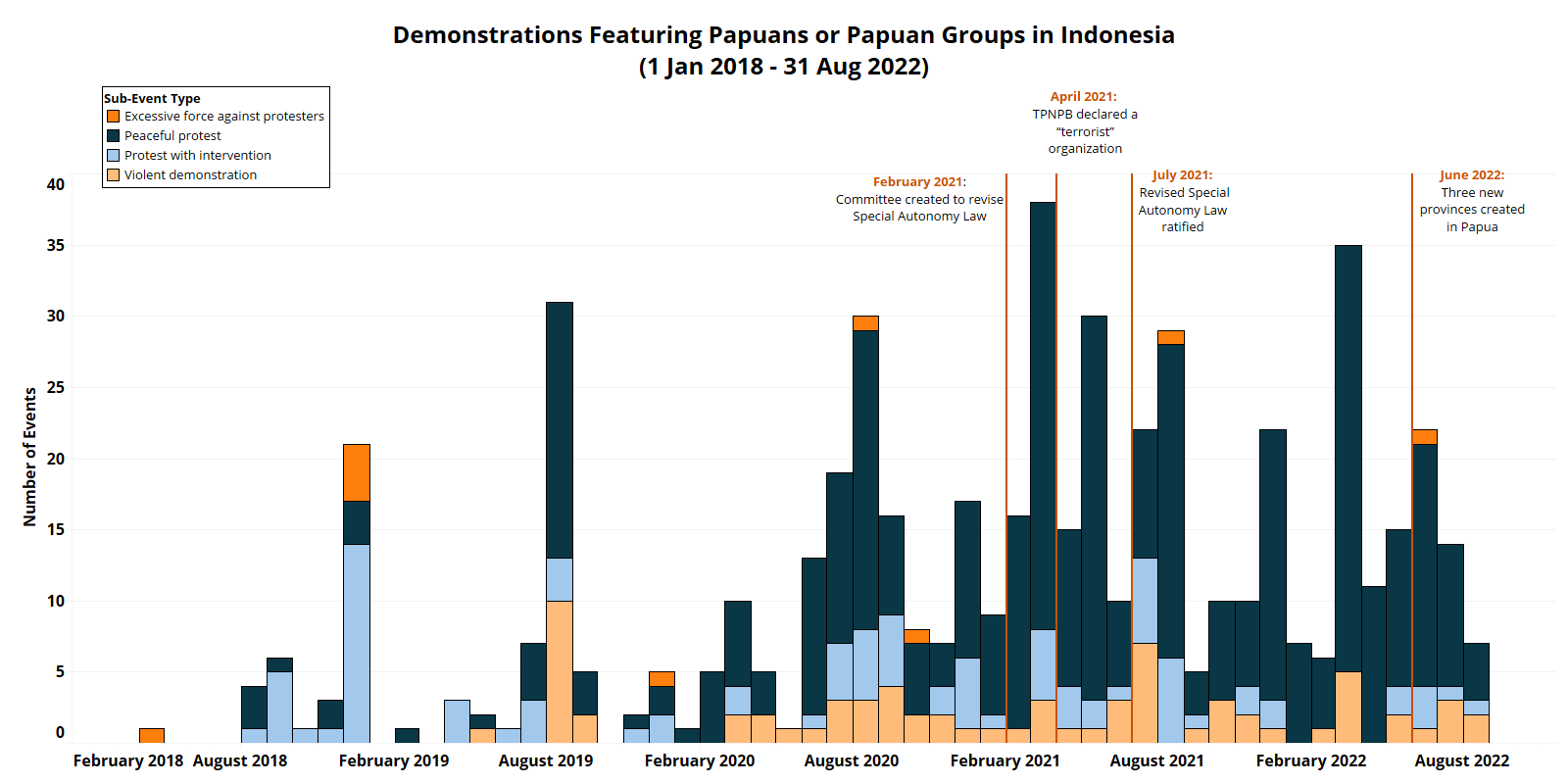

Aside from the armed conflict between the government and the TPNPB, calls for Papuan independence have also found their expression in public demonstrations. Demonstrations featuring Papuans and Papuan groups are met with disproportionate state intervention when compared to demonstrations not involving Papuans or Papuan groups. Such demonstrations increased significantly in 2021 (see figure below), driven by opposition to the revised Special Autonomy Law and the proposed creation of new provinces in the region.

The central government’s unilateral process of drafting and approving the Special Autonomy Law triggered protests by many pro-independence Papuans, who expressed frustration over the lack of consultation with the Papuan community (Papua Barat News, 11 April 2022). The government claims that creating new provinces will allow for better management of funds to accelerate development in the region, which they argue would improve the lives of Papuans (Pikiran Rakyat, 10 March 2022, DPR RI, 14 March 2022). However, many Papuans see this move as a way for Jakarta to increase its control and influence in the area (IPAC, 21 December 2021), potentially weakening demands for independence.

In February 2021, the Indonesian government created a special committee to oversee the revision of the Special Autonomy Law (Kompas, 10 February 2021). This contributed in March to the largest monthly spike in demonstrations since 2018 (see figure above). Demonstrations also centered around demands to investigate cases of state abuse against Papuans, as well as opposition to the military’s presence in the region. In March 2022, demonstrations again spiked around official visits by Indonesian parliament members to Papua to gather opinions regarding the creation of new provinces. On 30 June 2022, despite demonstrations against the plan, the parliament passed legislation for the creation of the new Central Papua, Highland Papua, and South Papua provinces.

While the demands of different Papuan groups may vary, a wide range of groups have been involved in organizing pro-independence demonstrations. Among these are the Papuan Students Alliance and the National Committee for West Papua (KNPB). The KNPB, formed in 2008, aims for a referendum to be held on the issue of Papuan independence (Free West Papua; Jubi, 1 December 2019). The group’s activism around Papuan independence has made it a target of state forces, with multiple reported arrests and attacks on the group (HumanRightsPapua, 12 December 2021; RZN, 10 May 2021).

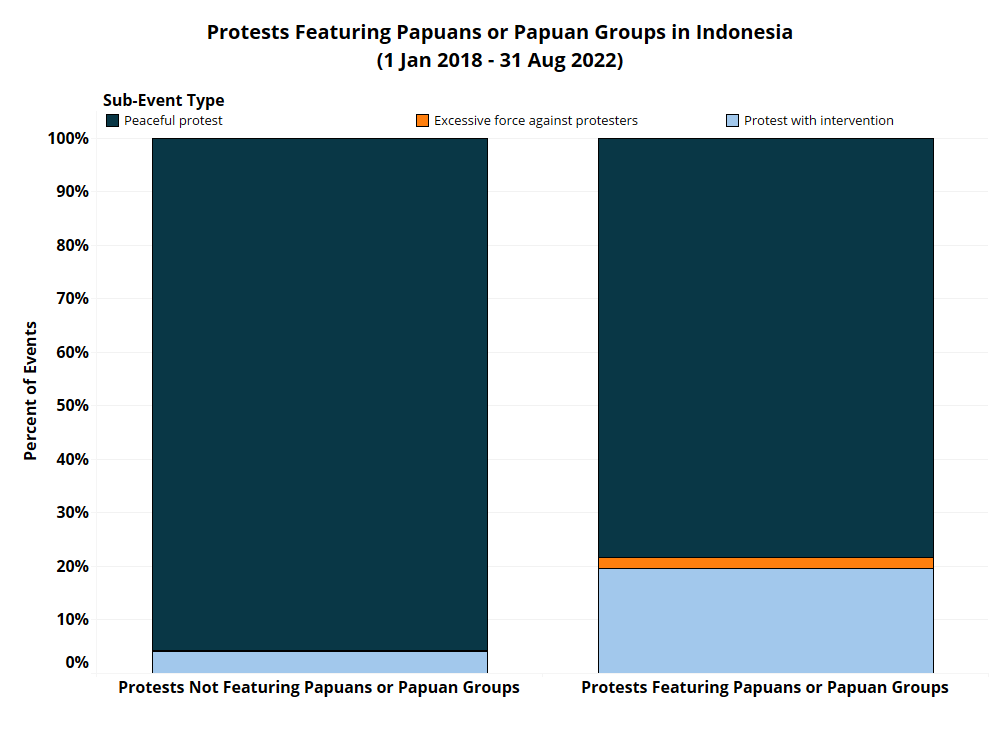

According to ACLED data, protests featuring Papuans or Papuan groups in which the protesters remain peaceful have been met with greater intervention or excessive force than those not featuring Papuans or Papuan groups (see figure below). From 1 January 2018 to 31 August 2022, 22% of all peaceful protests featuring Papuans or Papuan groups have been met with intervention or excessive force,5The majority of intervention in peaceful protests is carried out by state forces. In the remaining cases, rioters, often members of nationalist groups, have intervened. compared to only 4% of those not featuring Papuans and Papuan groups.6From 1 January 2018 to 31 August 2022, there were 486 protests featuring Papuans or Papuan groups in which the protesters remained peaceful. Of the total, 95 were met with intervention and 10 were met with excessive force. In the same time period, there were 5,541 protests not featuring Papuans or Papuan groups in which the protesters remained peaceful. Of this total, 228 were met with intervention and 6 were met with excessive force.

While the overall percentage of state interventions in these protests has fallen with each year since 2018, police continue to intervene and often forcibly disperse protesters at disproportionately high rates, sometimes with excessive violence. In a recent case of lethal excessive force against peaceful protesters, on 16 August 2021, a group of Papuans from the KNPB held a protest in Dekai district in Yahukimo regency in Papua province demanding the release of KNPB leader Victor Yeimo, opposing racism towards Papuans, and rejecting the Special Autonomy Law. The police intervened, dispersed the protest, and arrested over 40 protesters. A protester was shot and had to be taken to the hospital; he later died on 22 August 2021 (Suara Papua, 22 August 2021).

Conclusion

While President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo had initially campaigned on improving Indonesia’s policies in Papua (Katadata, 10 December 2021; Betahita, 8 July 2022), these improvements have largely failed to materialize. The issue of Papuan independence is likely to remain a significant driver of disorder in Indonesia for the foreseeable future, as the government continues to view the issue through a development lens rather than addressing the central political demands of Papuan groups. With Jokowi’s final term in office coming to an end in 2024, it remains to be seen how a new administration will address the issue of Papuan independence. Defense Minister Prabowo Subianto’s candidacy is cause for concern given his rights record in the region (CFR, 13 September 2022). While leading Kopassus (Indonesian special forces) on a mission in Papua to rescue hostages taken by OPM in 1996, Prabowo’s forces are alleged to have carried out reprisal attacks on civilians (ICRC, 27 August 1999).

The implementation of the Special Autonomy Law, particularly the creation of new provinces in the Papua region, will remain a flashpoint of contention. Many decisions concerning the new provinces remain to be made, including negotiations over land borders, the establishment of local governments in the newly created provinces, and the control and management of natural resources, including the distribution of mining revenue. Rather than serving to address underlying concerns in the region, the central government and local elites involved in the new administrations stand to benefit from the new provinces and the access to government projects and foreign investment that they entail (East Asia Forum, 11 June 2022).

Meanwhile, ongoing conflict between the TPNPB and state forces will continue to pose significant humanitarian concerns. The displacement of civilians due to the conflict has been notable in recent years. Aside from civilians caught in the crossfire, civilian targeting by each side will remain a threat to peace in the region. With the intended expansion of military and police bases into the new provinces (The Interpreter, 22 April 2022), Papuans may face greater scrutiny in relation to their support for the TPNPB. As well, the TPNPB’s declaration of war will likely mean continued targeting of non-Papuans seen as encroaching on Papuan land.

Visuals in this report were produced by Josh Satre and Danny Lord.