Beyond Riyadh: Houthi Cross-Border Aerial Warfare

2015-2022

17 January 2023

Introduction

On 25 March 2022, the Houthis launched a large-scale attack on Saudi Arabia using a combination of loitering munitions, ballistic missiles, and cruise missiles. This coordinated attack targeted oil refineries and energy infrastructure across Saudi territory, from Asir to the Eastern Province, and even threatened the Formula 1 Grand Prix in Jeddah. Yet, it turned out to be the last major gasp of the aerial war between Riyadh and the Sanaa-based government that had started in 2015. A few days later, on 2 April, a United Nations (UN)-mediated truce came into effect, which lasted until 2 October and, as of the time of writing, has effectively terminated Houthi cross-border attacks into Saudi and Emirati territories. In the current situation of relative stability, Saudi-Houthi talks are ongoing to renew and expand the truce.1Yemen News Agency, 21 December 2022

According to military expert Michael Knights, Houthi missile and drone technology has evolved significantly since the beginning of the conflict.2Knights, 1 April 2021 Between 2015 and 2016, Houthi forces relied predominantly on a pre-existing supply of rockets inherited from the Yemeni army stockpile. Due to Iranian expertise, however, they were later capable of developing extended-range missiles and unmanned aerial vehicle capabilities. Since 2018, a domestic military industry with headquarters in Sanaa and the northern city of Saada has developed, allowing for a prolonged campaign of rocket, drone, and missile strikes. Technological developments have also been accompanied by relevant shifts in the Houthis’ strategic approach to aerial warfare.

Aerial warfare has played a pivotal role in the regionalization of the civil conflict between the Houthis and the forces supporting Yemen’s Internationally Recognized Government (IRG). Since March 2015, the Saudi-led coalition (SLC) backed IRG forces with intense waves of airstrikes that slowed down Houthi military advances while inflicting heavy casualties and damage (for more, see this ACLED report on SLC activity in Yemen). Meanwhile, Iranian technology transfers to the Houthis broadened the arena of competition between regional powers, allowing the de facto Houthi authorities in Sanaa to strike military targets and civilian infrastructure in Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE).

It can be argued that the de facto Houthi authorities have used their missile forces to gradually compel the SLC to withdraw its forces from disputed territories in Yemen. This strategy of “compellence” has evolved into one of “deterrence,”3Samaan, 2020 as the Houthis included civilian infrastructure in their military targets while the UAE and Saudi Arabia have partially disengaged from the conflict. In the words of Thomas Schelling, compellence refers to “a threat intended to make an adversary do something (or cease doing something),” whereas deterrence uses threats to prevent the adversary from starting something.4Schelling, 1981, quoted in Samaan, 2020, p. 52

Drawing on recently updated ACLED data, this report examines the evolution of cross-border aerial warfare, focusing on rocket/missile5Based on ACLED data, it is not possible to consistently discern between the use of rockets and missiles, and this report does not use the two words in a technical sense. Indeed, a univocal definition of these two terms is hardly found in scholarly debates or military vocabulary. Furthermore, journalistic language tends to use them interchangeably. In this report, the rocket/missile distinction is replaced with an analytical categorization of these weapons based on the presence or absence of a guidance system. The assessment of this feature is primarily based on the reported name of the weapon, and, secondarily, on the description of the weapon provided by reporting sources. and drone attacks perpetrated by the Houthis in Saudi and Emirati territories between 2015 and the beginning of the UN-mediated truce in April 2022. It explores Houthi cross-border aerial warfare at the intersection of technological developments, local and regional political shifts, and military strategies. Based on these dimensions, it identifies four stages in the development of Houthi aerial warfare: an initial phase (2015-August 2016) characterized by a heavy reliance on the prewar stockpile, direct engagement with Saudi Arabia, and high levels of cross-border attacks; a second phase (September 2016-2018) marked by a gradual development of the domestic missile industry, rapprochement with Iran, and expansion of military targets; a third phase (2019) in which high-precision aerial weapons were used to deliver lethal attacks and maximize pressure on Saudi Arabia; and a final stage (2020-2022) characterized by the use of high-precision weapons as a means of deterrence, direct engagement with Saudi Arabia, and stabilization of the Yemeni-Saudi border.

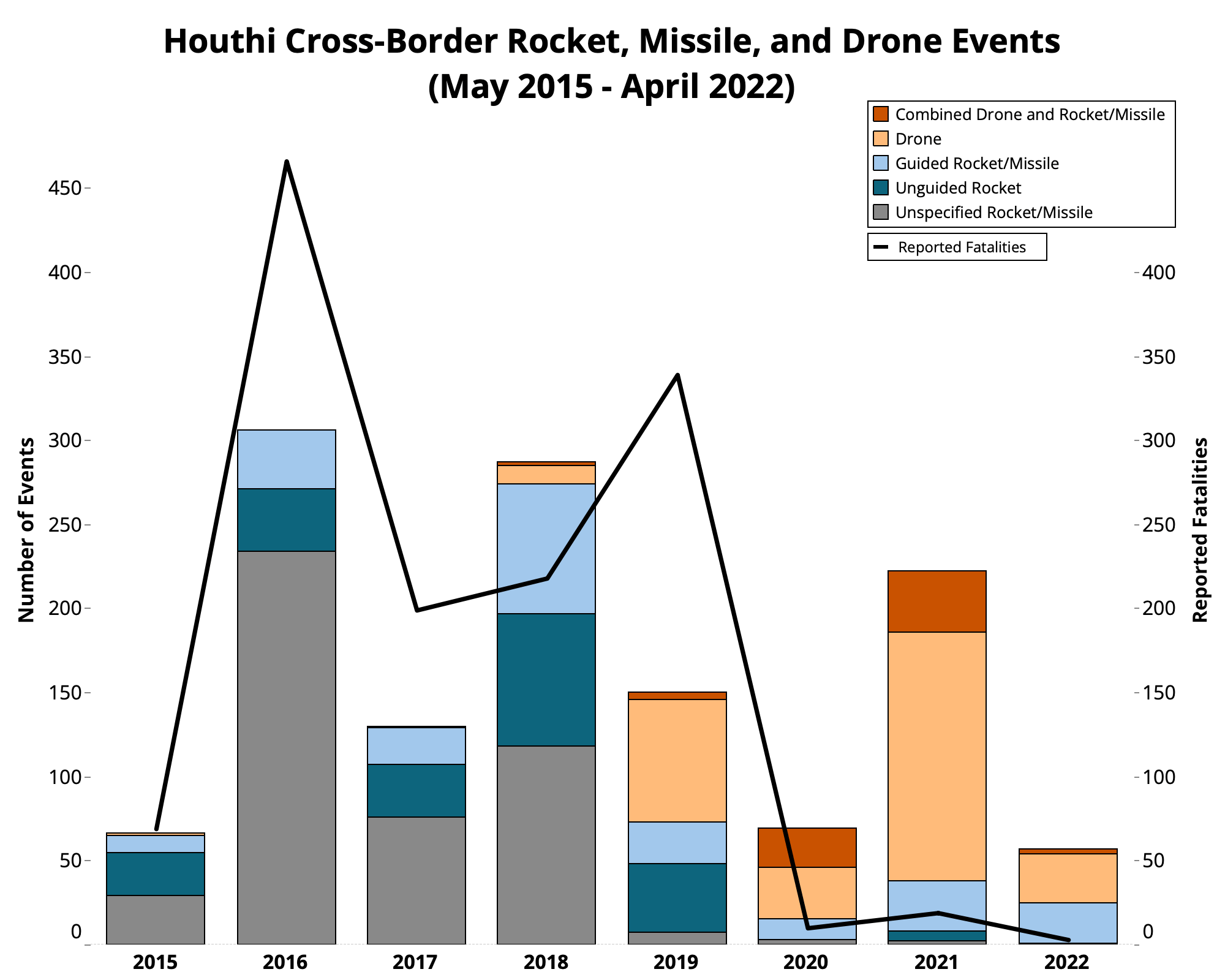

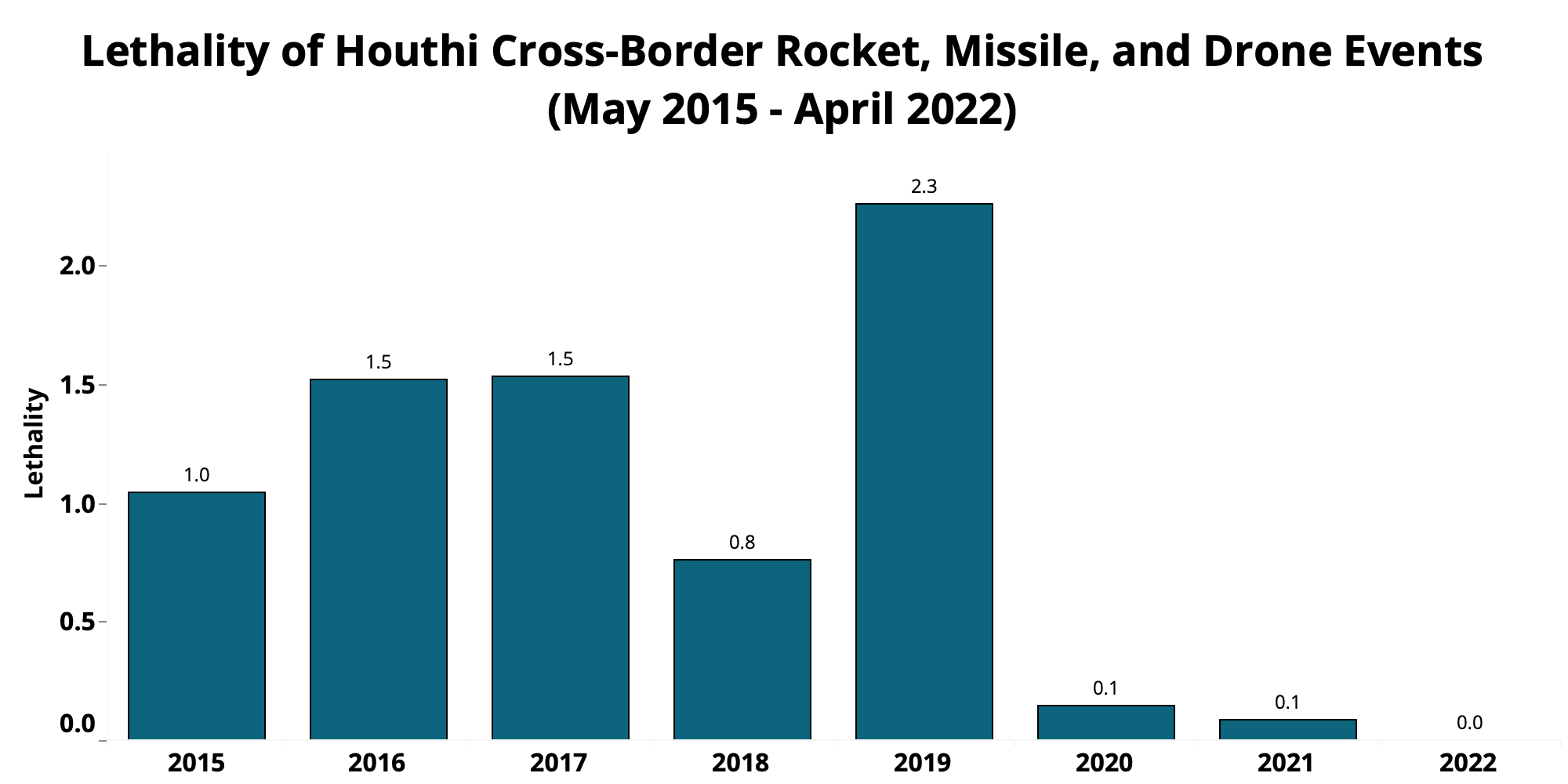

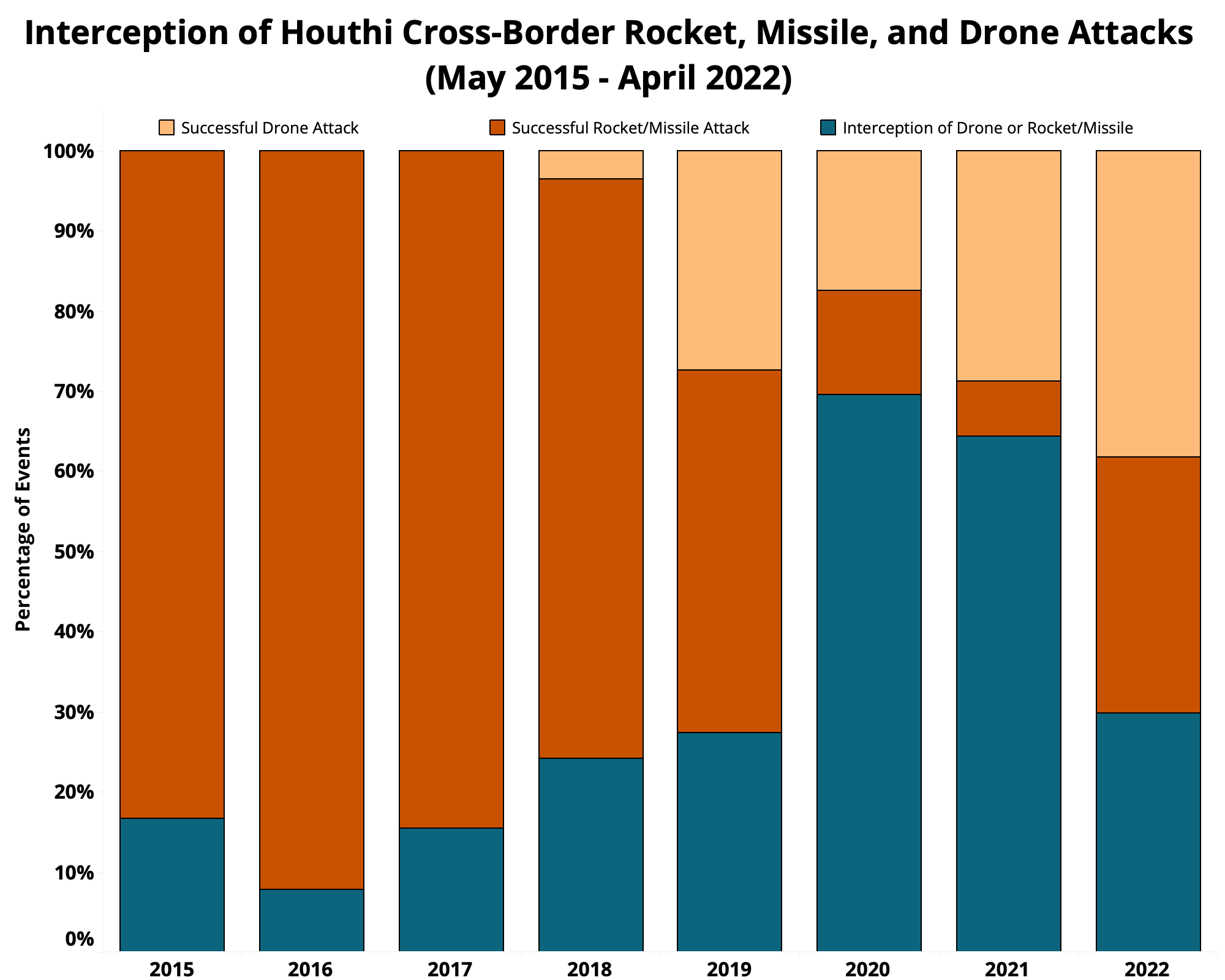

Analysis of ACLED data reveals some key trends. Between 2015 and 2 April 2022, the Houthis engaged in nearly 1,000 rocket/missile attacks and over 350 distinct drone attacks. The number of attacks involving unguided rockets has steadily decreased, while the use of guided rockets/missiles has increased from 15% of the yearly total in 2015 to 89% in 2022. This change suggests decisive technological improvements, and it is also associated with a decrease in the lethality of such attacks. Almost all deadly rocket/missile attacks occurred between 2015 and 2019. Drone attacks, which have outnumbered rocket/missile attacks since 2019, played a key role in enabling this shift, allowing for an expansion of military targets and strengthening Houthi deterrence credentials.

The Onset of Houthi Missile Warfare (May 2015-August 2016)

After seizing Saada city in March 2011, the Houthis expanded their territorial control and captured state armaments across northern Yemen.6Knights, September 2018 A strategic alliance with former President Ali Abdullah Salih allowed them to co-opt state officials and army brigades, paving the way for a takeover of Yemen’s capital city, Sanaa, in September 2014.7Al-Dawsari and Nasser, 2020 Between the fall of 2014 and the beginning of 2015, the Houthi-Salih alliance extended its grip over central Yemen and the Red Sea coast, and eventually moved further south to nearly capture the port city of Aden on 25 March 2015.

At each step of this military advance, the alliance acquired new weaponry. According to UN estimates, by the end of July 2015, Salih and the Houthis controlled around 68% of Yemen’s national arms stockpile, including missiles and aerial weapons.8United Nations Panel of Experts on Yemen, 2018, p. 36 It is difficult, though, to establish a precise account of the alliance’s initial weapons cache. According to the SLC, in March 2015, the cache included around 300 Scud missiles,9ACRSEG, 2 July 2015 but international reports differ on this point. The UN Panel of Experts on Yemen provides a lower estimate, assessing that the Yemeni Missile Defense Command had at least 18 SS-1 (Scud-B) and 90 Hwasong-6 (Scud-C) missiles.10United Nations Panel of Experts on Yemen, 2018 An earlier Congressional Research Service report confirms this figure, estimating an additional cache of at least 24 Tochka SS-21 ballistic missiles.11Congressional Research Service, 26 July 2005 As the war progressed, the Houthis converted an additional 200 V-755 surface-to-air missiles into land-attack free-flight rockets.12CSIS, June 2020

Even considering the highest estimate above (300 missiles in 2015), the size of the stockpile can hardly account for the number of cross-border rocket/missile events recorded by ACLED. In fact, between 2015 and July 2017 – when the army weapon stock was completely exhausted by the Houthis13United Nations Panel of Experts, 2018 – ACLED registers more than 400 rocket/missile events (see graph below).14CSIS, June 2020. During Operation Decisive Storm (26 March – 21 April 2015), the size of the prewar stockpile was further reduced by SLC airstrikes aimed at destroying Houthi missile capabilities.

Arguably, the ‘inherited’ missile stockpile was augmented by an undetermined number of Iranian weapons transiting through Yemen’s land and sea ports. In March 2015, an air bridge between Tehran and Sanaa ferried Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps trainers and equipment to the Yemeni capital, while an Iranian cargo ship unloaded 180 tons of military equipment in the Red Sea port of al-Salif.15Knights, September 2018 In addition, Iran reportedly stepped up the smuggling of small weapons and missile components through the Omani border in May 2016.16Reuters, 20 October 2016

The Houthis gained access to the Yemeni army missile stockpile in May 2015 through the Salih-linked 5th and 6th Missile Brigades. This was allowed by former President Salih, who was reluctant to enter into a direct conflict with Saudi Arabia and feared for his life after the SLC struck his house in May 2015.17Nevola and Shiban, 2020 Around the same period, the Houthis created a new missile force and established the Missile Research and Development Center.18CSIS, June 2020 The first Scud missile was launched by the Houthis on 26 May 2015, targeting King Khalid Air Base in Saudi Arabia’s Asir district. Situated near the southern city of Khamis Mushayt, the base was used by coalition fighter jets to launch raids against Yemen.19France24, 4 December 2015

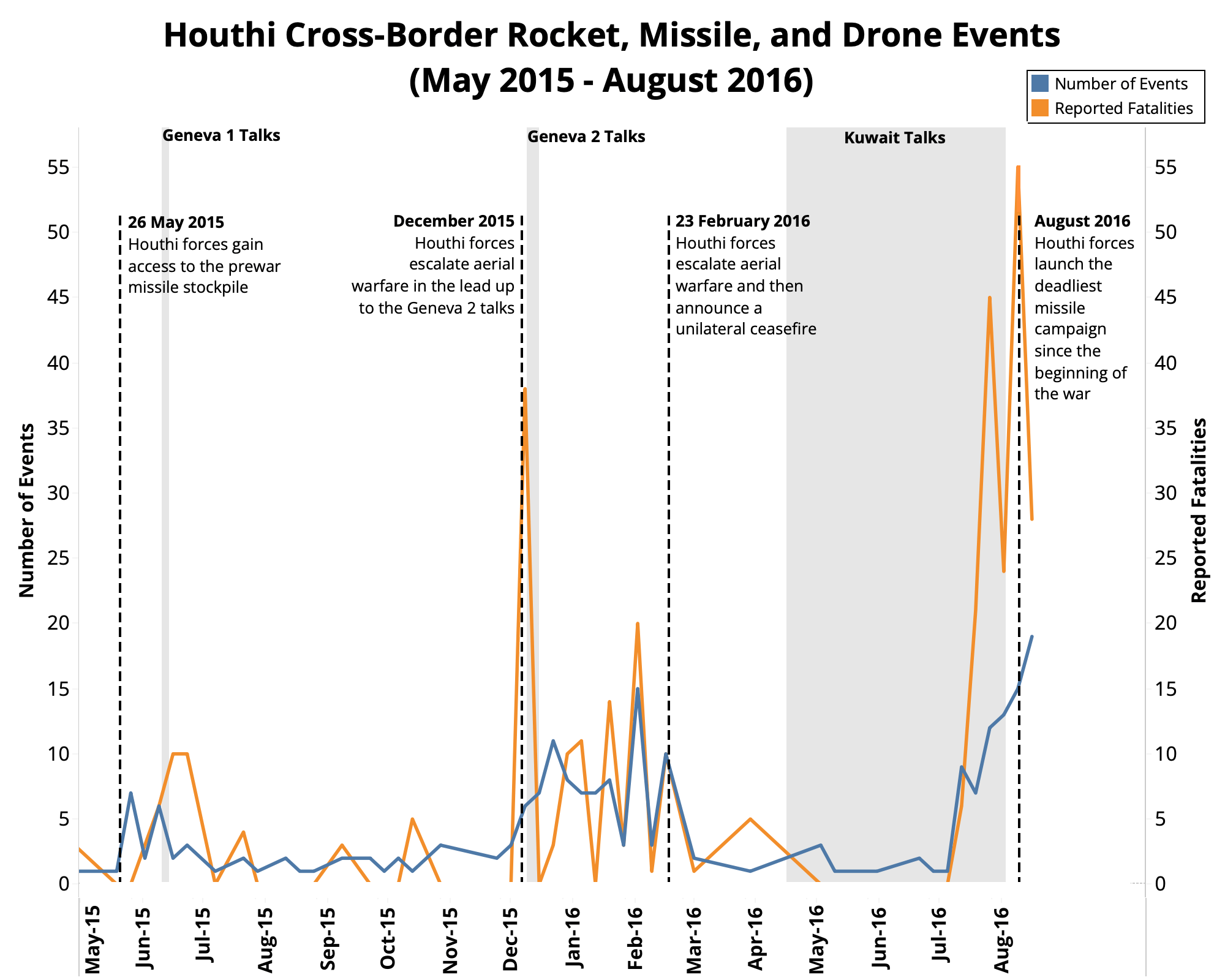

This Houthi attack inaugurated a strategy of compellence towards Saudi Arabia,20Samaan, 2020 characterized by the use of missiles to respond shot-on-shot to Saudi airstrikes. Between the end of May and the beginning of June, the Houthis had the upper hand militarily and appeared to escalate cross-border aerial warfare to leverage better negotiation terms ahead of the Geneva peace talks (15-19 June 2015). However, starting from December 2015, they adopted an ‘escalate to de-escalate’ approach surrounding peace talks and consultations. This approach consisted of an escalation of aerial warfare ahead of diplomatic talks, followed by a sudden reduction of cross-border attacks. Arguably, this pattern had a two-fold aim: first, leveraging better negotiation terms by demonstrating military capacity, and second, emphasizing a commitment to the cessation of hostilities by a halt to the attacks.

The ‘escalate to de-escalate’ tactic was first deployed in the lead-up to the Geneva 2 talks — convened by the UN on 15 December 2015 — when the Houthis embarked on a highly lethal campaign of cross-border missile/rocket attacks against Saudi Arabia (see graph below), and deployed the Qahir-1 rockets for the first time. Aerial warfare ceased in coincidence with the talks, only to resume on 18 December as IRG forces suddenly advanced in al-Jawf governorate.

Similarly, in 2016, the Houthis appeared to use cross-border aerial warfare to signal a shift in local and regional alliances. Cornered by the IRG’s military advance in Nihm district, in the northeast of Sanaa, the Houthis launched a coordinated missile campaign into five Saudi districts on 23 February 2016. Subsequently, they unilaterally suspended cross-border attacks, ostensibly signaling the political will to re-establish a channel of communication. After days of preparatory talks, Houthi spokesperson Muhammad Abdussalam traveled to Zahran al-Janub to engage in negotiations on 7 March,21Al Jazeera, 9 March 2016 which led to a nationwide ceasefire announced by the UN on 23 March.22United Nations, 23 March 2016

This case highlights how the Houthis employed aerial warfare to convey political messages at different levels. Indeed, the rapprochement with Saudi Arabia came at a sensitive time, just a few weeks after Riyadh had severed diplomatic ties with Tehran,23Al Jazeera, 4 January 2016 thus hinting at a distancing of the Houthis from Iran. Furthermore, the Houthis’ near-monopoly of missile capabilities allowed them to maneuver cross-border attacks autonomously from their ally, Salih, pressuring him to accept the ceasefire.

The UN-mediated ceasefire led to peace talks in Kuwait from 21 April to 8 August 2016.24Al Jazeera, 7 August 2016 During this period, armed clashes continued within Yemen’s territory at fluctuating levels, although Houthi cross-border missile/rocket attacks almost completely ceased (see graph above). Beneath the talks, the relationship between the Houthis and Tehran was developing in a new direction as Iran stepped up the transfer of small weapons and missile components to the Houthis in May. By the end of July, while the Kuwait talks were faltering, Houthi spokesperson Abdussalam announced a new rapprochement with Tehran during an interview with the Beirut-based television network, Mayadeen, in which he revived anti-Saudi rhetoric.25Abdulrahman, 19 July 2016 This major shift in regional politics was again underlined by the resumption of cross-border attacks.

The 8 August end of the Kuwait talks marked the beginning of a novel political phase. The Houthi-Salih alliance established a new political body, the Supreme Political Council (SPC), while souring direct communication channels with Saudi Arabia.26Leaf and DeLozier, 9 January 2019 In mid-August, the Houthis escalated cross-border attacks, launching the heaviest and deadliest missile campaign since the beginning of the conflict (see graph above).

Beyond Riyadh: Extended Range and Expansion of Military Targets (September 2016-2018)

In September 2016, the Houthi-Tehran rapprochement started to become apparent in the form of technological transfers. The Houthis unveiled the first-ever “locally made” ballistic missile, the Burkan-1,27Ansarollah, 3 September 2016 an extended-range version of a Scud missile based on the Iranian Shahab-1 missile.28CSIS, June 2020, p. 42; United Nations Panel of Experts on Yemen, 2018, p. 115. According to the 2018 UN Panel of Experts on Yemen report, the 5th and 6th Yemeni missile brigades might have had the expertise to manufacture the Burkan-1, but not to produce extended range missiles capable of targeting Riyadh. They concurrently re-branded the Yemeni Missile Forces, launching a new logo and new social media accounts. Extended-range technology opened the way for attacks on critical infrastructure deep into enemy territory. A symbolic opportunity to deploy the new missile unfolded on 8 October, after the SLC targeted a funeral in Sanaa with several airstrikes, reportedly killing more than 140 people and injuring hundreds.29The Guardian, 15 October 2016 The Houthis declared the attacks a ‘war crime’30Al Mayadeen, 9 October 2016 and launched a Burkan-1 missile against the city of Taif, located 36 kilometers away from Mecca. Concurrently, cross-border aerial warfare remained at heightened levels throughout October.

In November 2016, the Houthis abided by a ceasefire brokered by then-United States (US) Secretary of State John Kerry just before the end of President Barack Obama’s term,31Al Jazeera, 15 November 2016 leading to a temporary decrease in cross-border attacks. Overall, though, 2016 records the highest number of cross-border rocket/missile events for any year throughout the war and the highest number of associated reported fatalities. Arguably, this large-scale deployment of aerial weapons was facilitated by the prewar army stockpile, which approached exhaustion between the end of 2016 and mid-2017.32United Nations Panel of Experts on Yemen, 2018

In 2017, with the Houthi domestic missile industry still not fully mature,33Knights, 1 April 2021 the de facto government in Sanaa shifted its strategy for cross-border aerial warfare, reducing the frequency and number of attacks while emphasizing symbolic results. In particular, the Houthi leadership highlighted the achievement of new extended-range technology and expanded its list of military targets. On 6 February, the Burkan-2 missile — a “locally manufactured” weapon “developed from the Burkan-1”34Twitter @tonytohcy, 6 February 2017 — made it possible to strike Riyadh for the very first time, signaling the achievement of a range beyond the technical capacity of Yemeni engineers.35United Nations Panel of Experts on Yemen, 2018, p. 115 The operation on 6 February was framed as an act of retaliation for what the Houthis termed the “bloody massacres and unjust siege” perpetrated by the “American-Saudi aggression” on the Yemeni people.36Twitter @tonytohcy, 6 February 2017

The leader of the Houthi movement, Abdulmalik al-Houthi, commented on the milestone by heralding the upcoming release of further extended-range weapons and the ongoing effort to manufacture drones, highlighting the evolution of “local” technology from words to ballistic missiles.37Yemeni Press, 11 February 2017 By the end of February, a military exhibition showcased the latest products of the Yemeni Missile Forces, including new drones. However, such drone technology was not to be deployed until 2018.

Meanwhile, evolving political dynamics intervened at the domestic and regional levels. In March 2017, tensions started increasing within the Houthi-Salih alliance over a shifting power balance in the coalition.38Aysh, 27 April 2022 Seeing vulnerabilities in the alliance, Saudi Arabia reopened a direct channel of communication with Salih, who had grown increasingly dissatisfied with the Houthis.39Nevola and Shiban, 2020 Concurrently, the UAE stepped up its involvement in the war, injecting new finances into the training of ‘counter-terrorism’ units known as the Security Belt Forces.40United Nations Panel of Experts on Yemen, 2018

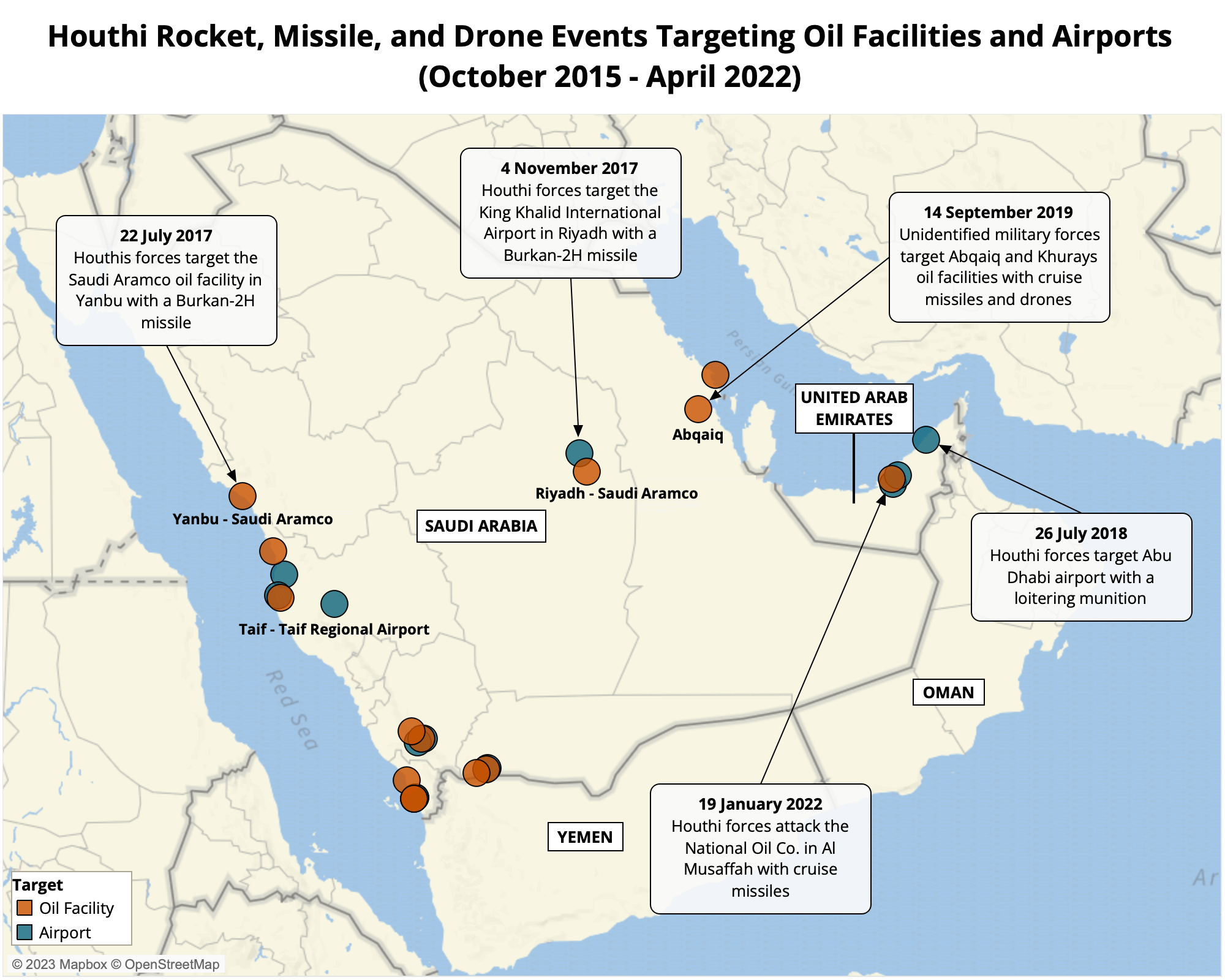

Facing domestic and regional threats, the Houthis launched Operation Beyond Riyadh, expanding their military targets in Saudi Arabia to include oil facilities.41Al Manar, 23 July 2017 On 22 July 2017, a Burkan-2H missile struck the Saudi Arabian Oil Company (Aramco) oil refinery of Yanbu, located 1,800 kilometers from the northern Yemeni border (see map below). In a broadcast speech, Abdulmalik al-Houthi announced a military escalation until the end of the year and warned the UAE that Dubai’s strategic facilities fell within the range of the Burkan-2H.42Al Akhbar, 24 July 2017 Notably, the use of the Burkan-2H — which included parts of the Iranian Qiyam-1 missile — provided proof of Iran’s supply of components to the Houthis.43United Nations Panel of Experts on Yemen, 2018

In November 2017, the coalescence of international and local developments brought about a further escalation. Ahead of US President Donald Trump’s visit to Saudi Arabia, planned for 5 November, the Houthis struck King Khalid International Airport in Riyadh with a Burkan-2H missile. Observers interpreted the attack as a symbolic message against Trump’s support for the SLC’s intervention in Yemen and the choice of a civilian target in Saudi Arabia as showing Riyadh’s vulnerabilities.44Al Monitor, 16 November 2017 It was a turning point for the conflict, with Saudi Arabia subsequently imposing a complete blockade of Yemen’s air, land, and sea ports,45Reuters, 6 November 2017 strengthening what the Houthis termed the “economic war” against the Yemeni people and bolstering concerns of an impending humanitarian catastrophe.46Spiegel, 19 May 2017 UN reports also revealed evidence of Iran’s involvement in supplying weapons and technology to the Houthis.47United Nations Panel of Experts on Yemen, 26 January 2018

Between 2017 and 2018, Yemen’s political landscape was completely reshaped. The killing of Salih in December 2017 shifted the balance of power in Sanaa in favor of the Houthis. Meanwhile, in April 2018, the UAE spearheaded a military offensive on Yemen’s west coast with the aim of retaking the port city of al-Hudayda. The forces, consisting of UAE recruits and UAE-backed local troops, closed in on the city in June, preparing for an all-out assault. Then-UN Special Envoy for Yemen Martin Griffiths opposed the operation, arguing it would “take peace off the table” and cause a humanitarian catastrophe.48Office of the Special Envoy of the Secretary-General for Yemen, 17 April 2018 Eventually, the UN efforts led to a halt to the hostilities on 1 July 2018,49Reuters, 1 July 2018 though stirring resentment among UAE officials.50Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, 30 January 2020

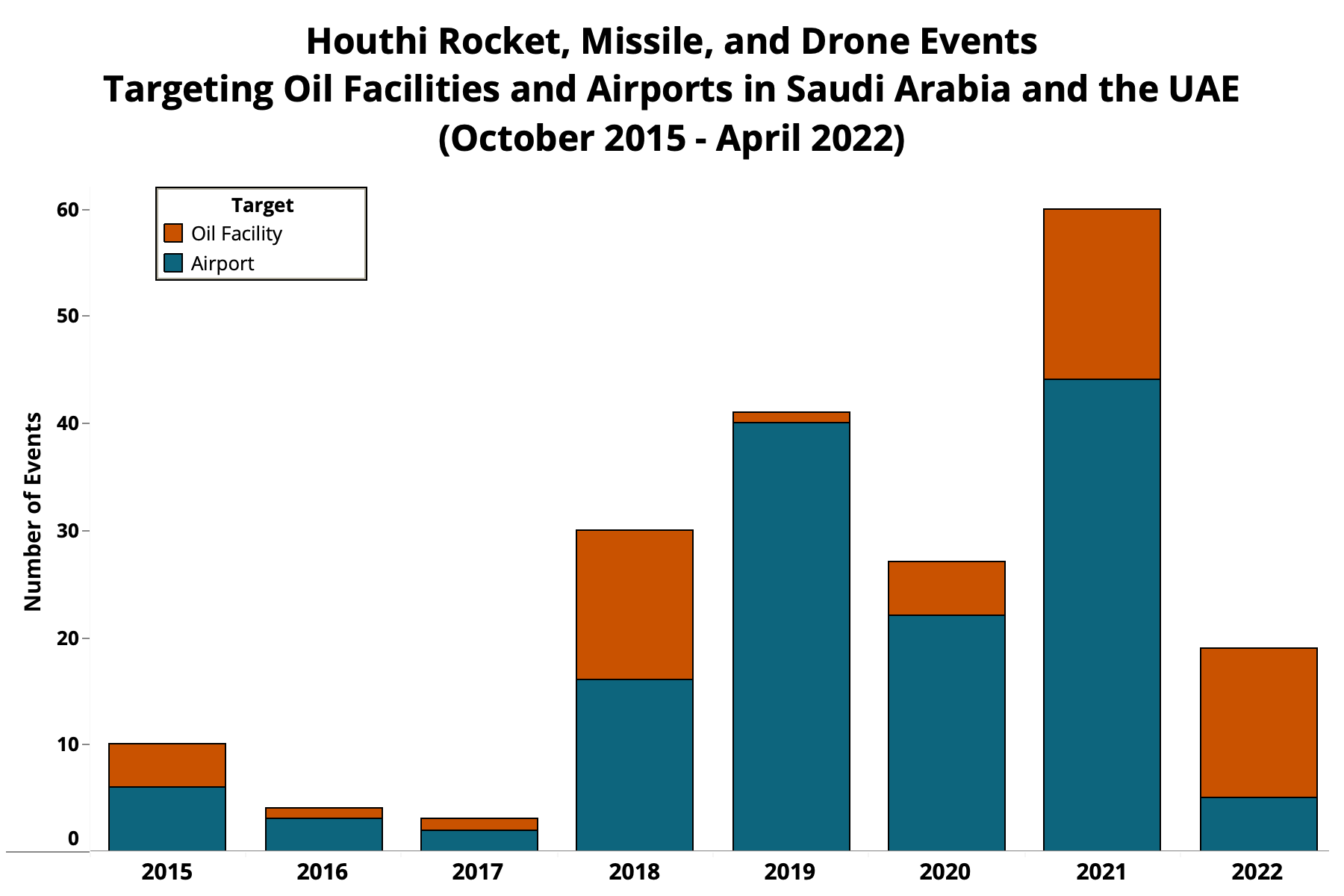

Despite the UAE-led advance in al-Hudayda, the Houthis did not follow through on their threat to strike Abu Dhabi with Burkan-2H missiles. Rather, rocket/missile attacks were deployed on a large scale against Saudi Arabia, likely to compel Riyadh to pressure the UAE out of al-Hudayda. ACLED data show that cross-border missile attacks increased in April 2018 by 77% compared to the month prior and remained at similar levels in May. Critically, the Houthis escalated their attacks on oil refineries and civilian airports, which increased nine-fold in 2018 relative to the year prior (see graph below). After the ceasefire, in July, the attacks dropped to the lowest level since December 2017.

The Houthis made use of the ceasefire to showcase technological developments and replicated their tactic of ‘escalating to de-escalate.’ On 26 July, conversations took place between Griffiths and SPC President Mahdi al-Mashat to pave the way for future peace talks.51Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, 5 August 2018 This meeting was preceded and followed by the first-ever extended-range drone attacks launched by the Houthis, targeting a Saudi Aramco oil facility on 22 July and Abu Dhabi International Airport on 26 July. As emphasized by then-Supreme Revolutionary Committee leader Muhammad Ali al-Houthi, the attacks aimed to deter further UAE involvement in the conflict and “open the way for a political process” through drone operations.52Twitter @Moh_Alhouthi, 26 July 2018 The use of drones remained very limited throughout the year, suggesting that Houthi drone capacity was still at an embryonic stage in 2018. Nonetheless, these attacks anticipated the decisive role of drone technology in targeting civilian objectives. Although UN-mediated talks planned for September failed to take place, the Stockholm agreement sanctioned a ceasefire in al-Hudayda in December 2018.

Lethal Aerial Warfare (2019)

In 2019, Houthi aerial warfare appeared to push the strategy of compellence further, increasing the lethality53In ACLED’s definition, ‘lethality’ refers to the rate of deadliness – fatalities divided by events. of attacks to curb Riyadh’s operations on the Yemeni-Saudi border and re-establish a channel of communication between Sanaa and Riyadh. This was mostly dictated by political developments and deliberate military strategies. In 2019, the Yemen conflict stalled on all the main frontlines. While the Houthis greatly reduced the number of cross-border missile attacks toward Saudi Arabia, the lethality of missile events markedly increased, reaching the highest yearly level recorded by ACLED throughout the conflict (see graph below). Arguably, this spike in lethality was not determined by the deployment of new high-precision technology, but rather, a general determination to cause military casualties within Saudi ranks.54This is demonstrated by similar levels of lethality recorded for the use of guided, unguided, and unspecified rockets.

Around the same time, increased drone capacity allowed for an expansion of cross-border operations. In January 2019, Houthi loitering munitions targeted Saudi positions along the Saudi-Yemeni border, reportedly resulting in several fatalities. Drone attacks continued in the subsequent months, and acquired a new dimension in May, when Saudi civilian airports started to be systematically targeted. In June, Houthi spokesperson Muhammad Abdulsalam described civilian airports as a military target in response to the SLC’s “siege of Sanaa airport.”55Twitter @abdusalamsalah, 9 June 2019

Houthi cross-border attacks escalated during the summer. Between June and September 2019, ACLED records 37 rocket and drone events targeting Saudi civilian airports. In addition, the increasing use of guided rockets reportedly resulted in 62 Saudi fatalities in August alone. This escalation reached its climax on 14 September, when a joint Houthi-Iranian attack targeted Saudi Aramco facilities in Abqaiq and Khurays. The incident temporarily knocked out more than half of Saudi Arabia’s oil output and nearly 5% of the global oil supply.56Al Jazeera, 30 September 2019 Although the missiles targeting Saudi Aramco were likely launched from Iranian or Iraqi territory, the Houthis claimed responsibility for the attacks, lending their partner plausible deniability. A few days after the attack, on 20 September, the Houthis declared a unilateral ceasefire.57Reuters, 20 September 2019

The attacks were key to shifting Saudi Arabia’s position towards the Houthis, especially after the UAE announced a drawdown of troops in the summer of 2019, weakening the SLC’s deployment to Yemen.58Financial Times, 11 October 2019 On 27 April 2019, Saudi Arabia declared a partial ceasefire that was publicly rejected by the Houthis.59Jalal, 1 October 2019 Nonetheless, Houthi-Saudi back-channel talks continued, leading to a substantial decrease in cross-border political violence. From October through the end of December 2019, ACLED data show that Houthi rocket and drone attacks against Saudi Arabia ceased. Furthermore, cross-border battle events between Houthi and Saudi forces dramatically dropped and, after November, came to a halt.

A Shift Towards Deterrence (2020-2022)

By the beginning of 2020, the September 2019 ceasefire between the Houthis and Saudi Arabia had collapsed. The Houthis advanced into al-Jawf governorate, threatening to inflict a fatal blow to the IRG by closing in on the capital of Marib governorate. Meanwhile, they resumed cross-border rocket and drone attacks. The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic reinforced Saudi Arabia’s inclination to disengage militarily from Yemen, pushing Riyadh to implement long-awaited humanitarian measures in February.60Al Masdar Online, 4 February 2020; PBS, 16 February 2020 However, despite ongoing back-channel talks and a unilateral ceasefire announced by Saudi Arabia on 8 April,61Saudi Press Agency, 9 April 2020 the Houthis took advantage of the pacified northern border to redirect their military efforts in central Yemen, most notably in al-Bayda and Marib.

Against the backdrop of an overall stabilization of activity along the Yemeni-Saudi border, Houthi rocket and drone attacks against Saudi Arabia evolved in a new direction. In 2020, ACLED records a substantial drop in the number of unguided rockets events, arguably as a result of the complete depletion of the stockpile of Zilzal rockets. In contrast, guided rocket events remained at levels comparable to those recorded in 2019. However, their lethality decreased significantly compared to the year prior, with the overall number of reported fatalities associated with these events dropping from over 350 in 2019 to 10 in 2020. Likewise, in 2020, no fatalities were reported from the impact of drone attacks. Reduced lethality hinted at a new strategy of deterrence. The achievement of high-precision, extended-range technology allowed for symbolic attacks on key infrastructure which proved ever more effective in preventing enemy action.

Yet, a second factor also arguably impacted on the lethality of Houthi attacks: an improvement in the effectiveness of Saudi air defense. ACLED data show that the interception rate by Saudi forces doubled in 2020 relative to 2019, rendering the majority of Houthi drone and missile attacks in 2020 ineffective (see graph below). The interception rate for drones reached 77%, while the rate for rockets/missiles hit 40%. Indeed, after the September 2019 attacks, Saudi Arabia received new ground-based air defense systems from the US and started developing novel counter-drone systems.62Al Arabiya, 20 February 2020; Defense News, 8 January 2020 In response to Saudi interceptions, the Houthis developed new combined drone and missile attacks. In the past, the Houthis had deployed suicide drones to down Saudi defense systems and open the way for missile attacks.63Conflict Armament Research, March 2017 However, these combined attacks saw a 360% increase in 2020 compared to the year prior, and were especially directed against oil refineries.

After a standstill in January 2021, the Houthis renewed their operations to take Marib in February. Almost concurrently, they resumed drone and missile attacks against Saudi Arabia, which had ceased during the month prior. Overall, in 2021, cross-border aerial attacks increased in number and frequency: drone events by 377%, missile events by 153%, and combined attacks by 56%. Despite these upticks, the lethality of these events saw a further decline, reaching the lowest levels since the beginning of the war. By the end of 2021, military developments led to an unexpected turn in the conflict. Although stagnating during the summer, the Houthi advance in Marib picked up in October, leading to their units seizing Harib junction while besieging the outskirts of Marib city. The impending fall of Marib was averted by the UAE-backed Giants Brigade, which provided support to the anti-Houthi camp, recapturing territories in Shabwa and Marib between December 2021 and January 2022. The UAE’s renewed involvement triggered an immediate reaction from the Houthis.

On 3 January 2022, the Houthis hijacked a UAE-flagged cargo ship off al-Hudayda port, imprisoning its crew.64Al Arabiya, 3 January 2022 They subsequently announced Operation Yemen Hurricane, targeting Abu Dhabi and Dubai airports, along with the Musaffah oil refinery, with Quds-2 cruise missiles on 17 January. In connection with the latter attack, the Houthi army spokesperson, Yahya Sarii, announced a further expansion of military targets to include “vital sites and facilities” in UAE territory.65Twitter @Yahya_Saree, 17 January 2022 Two more attacks followed on 24 and 31 January, conducted with Sammad-3 drones and Zulfiqar missiles. The latter targeted Abu Dhabi in coincidence with the first visit of an Israeli president, Isaac Herzog, to the UAE,66Twitter @Isaac_Herzog, 30 January 2022 likely to symbolize opposition to Abu Dhabi’s normalization of diplomatic relationships with Israel.

The Houthi operations against the UAE were accompanied by an extensive social media campaign, successfully amplified by other online opponents of the UAE. The operations were perceived by some scholars as proving the Houthis’ autonomy from Iran, threatening Tehran’s ongoing efforts to mend relations with the UAE.67Atlantic Council, 24 January 2022 Further, the attacks attempted to undermine Abu Dhabi’s image as a safe ‘liberal playground,’ with several Houthi leaders publicizing messages inviting foreign investors to abandon the UAE.68Twitter @M_N_Albukhaiti, 24 January 2022

In February and March, the newly appointed UN Special Envoy for Yemen, Hans Grundberg, engaged in several rounds of negotiations with the warring parties, which resulted in the nationwide truce coming into effect on 2 April. The truce was preceded by a large-scale cross-border Houthi attack that targeted several locations in Asir and Jizan districts with ballistic missiles, while cruise missiles targeted Riyadh and Saudi Aramco in Jeddah. The attack replicated the Houthi pattern of ‘escalating to de-escalate,’ and it was followed by SPC President Mashat’s announcement of a unilateral ceasefire accompanied by a peace proposal.69Yemen News Agency, 27 March 2022

Looking Forward

Over more than seven years of war, Houthi cross-border aerial warfare has evolved under the influence of several factors: technological improvements, shifts in local and regional alliances, and strategic military considerations. Between 2015 and 2019, the Houthis mainly deployed aerial attacks to compel the SLC to de-escalate its involvement in supporting the IRG. After the depletion of the Yemeni army stockpile, improvements in the range and precision of Houthi weapons enabled the targeting of sensitive infrastructure — including oil facilities and airports — in the depth of enemy territory, reaching peak effectiveness and lethality in 2019. Starting from 2020, a steady drop in the lethality of drone and missile events reflected a shift from an apparent strategy of compellence to one of deterrence. Cross-border attacks turned into a form of political messaging, enhanced by media campaigns. Nevertheless, recurrent patterns in aerial attacks — such as the strategy of ‘escalating to de-escalate’ — seem to have continued despite these developments, and can be analyzed to envisage future courses of action.

The UN-mediated truce, which came into effect on 2 April 2022 and ended on 2 October, resulted in the almost complete halting of Houthi cross-border attacks against Saudi Arabia and the UAE. Yet, the precarious stability ensuing from the truce has granted the Houthis the possibility to replenish their missile and drone stocks, while developing new technology. A scenario such as that which materialized in the aftermath of the 2016 Kuwait talks — a relapse of missile attacks re-energized by technological developments — is a viable possibility. Since September 2020, the Houthis have been showcasing novel tools of deterrence, which include mines on land and at sea, a shore-based missile system, Shahid 131 and 136 drones, and an extended-range Quds-3 cruise missile.70Yemen News Agency, 1 September 2022; Defence Update, 27 September 2022 In addition, they have further expanded their military targets. Recent attacks on oil tankers in Shabwa — aimed at preventing Yemen’s oil and gas exports, while pressuring the IRG and SLC to pay state salaries in Houthi-held areas — have been highly effective in leveraging Houthi demands. Such attacks are a continuation of the deterrence strategy, and highlight the SLC’s vulnerability to high-precision strikes on civilian infrastructure.

While UN-led negotiations are currently stalling,71Office of the Special Envoy of the Secretary-General for Yemen, 24 November 2022 one of three scenarios is likely to materialize in the future. One is that back-channel talks between Saudi Arabia and the Houthis will lead to peace negotiations and political talks with Yemeni parties. A second possibility is that the current state of low-level hostilities will continue indefinitely, sustained by an increase in the size and effectiveness of the Houthis’ deterrence capacity. The last option, which has already been plotted by the Houthis,72Ansarollah, 14 November 2022 would be an escalation in three phases: first, an increase in domestic drone attacks to prevent oil exports from Yemen; second, a resumption of regional attacks against Saudi and Emirati oil facilities; and third, international attacks targeting shipping companies in the Red Sea and Bab al-Mandab. In this last scenario, technological developments could allow the Houthis to internationalize the conflict beyond the current involvement of the SLC in the Yemen war.

Visuals in this report were produced by Luca Nevola, with Ana Marco.