Deadly Rio de Janeiro:

Armed Violence and the Civilian Burden

14 February 2023

Introduction

The public security situation in Brazil is complicated, and particularly in Rio de Janeiro state, which has high levels of violence and criminality. The presence of multiple different criminal groups fighting for territory, coupled with abusive government measures to tackle criminal activity, has created a deadly, high-risk environment for civilians in the state. In 2021, Rio de Janeiro registered 27 violent deaths per 100,000 inhabitants, a rate lower than states like Bahia and Ceará but significantly higher than the national average of 22. Rio de Janeiro also ranked first among Brazilian states in the number of deaths recorded during police interventions, with at least 1,356 people reportedly killed.1Fórum Brasileiro de Segurança Pública, ‘Anuário Brasileiro de Segurança Pública,’ 2 August 2022 In May 2021, for example, a police operation against drug traffickers in the Jacarezinho community in Rio de Janeiro city resulted in 29 reported fatalities. While authorities claimed that all those killed in the operation were linked to criminal groups, witnesses reported that police officers entered civilian houses and carried out extrajudicial executions.2Human Rights Watch, ‘Brasil: Investigue Comando da Polícia do Rio por operação no Jacarezinho,’ 31 May 2021 The Jacarezinho operation was the deadliest single event recorded by ACLED in Brazil in 2021. A year later, in May 2022, military and federal police forces clashed with the Red Command (CV) in the Vila Cruzeiro community in the Penha Complex, resulting in at least 26 reported fatalities, including civilians. These are not isolated incidents, but rather indicative of the increasing lethality of violence in Rio de Janeiro in 2021 and 2022, and the rising threat to civilians.

The results of the general elections in October 2022 suggest that there will be continuity of current public security policies aimed at addressing violence and criminal activity in Rio de Janeiro. The right-wing Rio de Janeiro Governor Cláudio Castro was re-elected in the first round of the elections on a platform that promotes a security agenda focused on police action and operational transparency. It is expected that he will continue to promote police operations as the main method to curb organized crime in the state.3Igor Mello, Ruben Berta and Lola Ferreira, ‘Cláudio Castro (PL) é reeleito governador do Rio de Janeiro,’ UOL, 2 October 2022 Recent controversial state policies include the Cidade Integrada (Integrated City) project, launched in early 2022, which focuses on the occupation and heavy presence of military police in favelas and poor communities. Analysts have argued this model has already proven unsuccessful for multiple reasons, including its high lethality rates.4Jeniffer Mendonça, ‘O que propõem os candidatos ao governo do RJ na segurança pública,’ Ponte Jornalismo, 28 September 2022

In contrast, at the federal level, President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva has a new team for public security matters that has received praise for its selection of several recognized specialists, academics, and politicians.5Leonardo Martins, ‘PMs não são ouvidos em transição de Lula, diz diretor do Fórum de Segurança,’ UOL, 17 November 2022 Lula has also endorsed the implementation of comprehensive public policies and careful use of police action,6Divulgação de Candidaturas e Contas Eleitorais, ‘DIRETRIZES PARA O PROGRAMA DE RECONSTRUÇÃO E TRANSFORMAÇÃO DO BRASIL LULA ALCKMIN 2023-2026 COLIGAÇÃO BRASIL DA ESPERANÇA,’ August 2022 opposing former President Jair Bolsonaro’s promotion of increased access to firearms for civilians and harsher police operations as a way to reduce violence.7Divulgação de Candidaturas e Contas Eleitorais, ‘PLANO DE GOVERNO 2023-2026 Bolsonaro,’ 2022 One day after being sworn in, Lula revoked a series of measures from the Bolsonaro government that facilitated and expanded the population’s access to firearms and ammunition,8Raquel Lopes and Victoria Azevedo, ‘Lula inicia revogaço e suspende aquisição de armas de uso restrito para CACs,’ Folha de São Paulo, 2 January 2023 meeting a campaign promise to improve gun control regulations as a means of decreasing smuggling and hindering weapons access for criminal groups.9Lula Official Website, ‘Ministério da Segurança Pública vai conter tráfico de armas e drogas nas fronteiras, diz Lula,’ 20 October 2022

While the overall rate of violence in Brazil remains at significantly lower levels than the heights of 2018, analysis of updated ACLED data drawing on new information from Fogo Cruzado, a Brazil-based research institute, reveals worrying developments for the state of political violence in the country, specifically in Rio de Janeiro. The data show an increase in the deadliness of armed violence in Rio de Janeiro, with reported fatalities surpassing 1,000 in 2021 and 1,250 in 2022, compared to just over 760 in 2020. Clashes involving state forces account for a disproportionately large share of reported fatalities. At the same time, violence targeting civilians increased by 17% between 2020 and 2021 and by 48% between 2021 and 2022, while reported civilian fatalities during the same periods increased by 44% and 26%, respectively. Poor communities, the Black community, and other civilians involved in investigations against militias and gangs are at particularly high risk of targeted attacks. In a city and state long engulfed in violence, the increasing death toll points to the enduring grip of gang-related conflict in Rio de Janeiro.

ACLED data collection on political violence in Brazil relies on over 50 sources, ranging from local newspapers to international media, in both English and Portuguese, which researchers review weekly.10For more on ACLED coding, see the ACLED Methodology and Coding Decisions around Political Violence and Demonstrations in Brazil and the Resource Library. The completion of a supplementation project has introduced new data to the ACLED dataset based on information from Fogo Cruzado, covering 2018 to the present. Fogo Cruzado is an institute that uses technology to produce and disseminate open and collaborative data on armed violence. Fogo Cruzado’s objective is to strengthen democracy, fight for social transformation, and the protection of civilian life. Using its innovative methodology, the institute’s data lab produces more than 20 new indicators of violence in the metropolitan regions of Rio de Janeiro and Recife, and it recently expanded to other Brazilian cities, such as Salvador. Fogo Cruzado receives information on armed violence events through a cell phone application, which is checked in real time by a team of experts in the regions where it operates. This information is available in the first open database on armed violence in Latin America, accessible for free through the institute’s API.

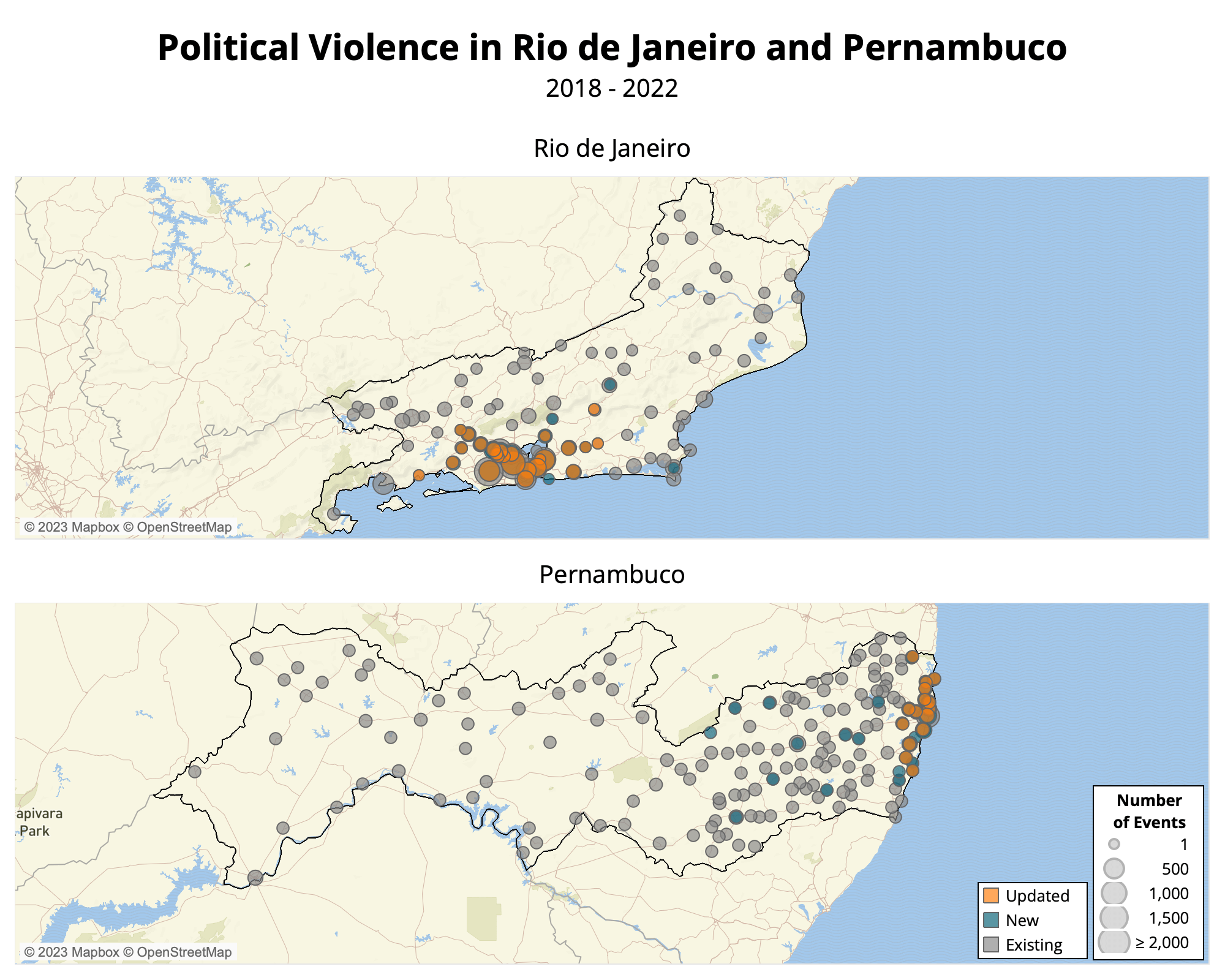

The addition of Fogo Cruzado data adds almost 4,000 new political violence events to the ACLED dataset and provides additional detail and information to more than 2,600 events already in the dataset, allowing for more detailed analysis (see map below). The supplementation project has significantly bolstered ACLED’s coverage of the activity of drug trafficking groups and police militias in the country, specifically for Rio de Janeiro state.

The newly publicly-available data also add over 3,900 additional reported fatalities to ACLED dataset’s fatality estimate for Brazil, 71% of which stemmed from armed clashes, with the remaining fatalities stemming from attacks against civilians. Of those armed clashes, 90% involved state forces clashing with criminal groups. Although purely criminal activity is not included in the ACLED dataset, organized criminal violence is included when it is used to meet overtly political goals and when it directly and fundamentally challenges public safety and security. In these scenarios, criminal groups engage in illicit economic activity, threaten the state’s ability to provide security to its citizens, and even offer social services in exchange for illegal fees. The ACLED dataset only includes Fogo Cruzado events that fall under certain forms of criminal violence that impact territorial control and the stability of the state. For all Fogo Cruzado events, see their website here.

Background

The first organized gangs appeared in Brazil around the 1970s in a national context of accelerating urbanization in the main cities. As cities began to grow fast, so did inequality and unemployment, leaving space for the emergence of illicit economies in peripheral areas.11Lia Vasconcelos, ‘Urbanização – Metrópoles em movimento,’ Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada, 5 May 2006 While the government’s provision of basic services in these areas was minimal, its presence was always felt due to the actions of state forces. This included evictions led by police and military officers, and law enforcement operations against residents. While the federal government tried to curb the spread of criminal groups by arresting individuals involved with illicit activities, it also created a scenario that unintentionally promoted its growth.12Jean Claude Chesnais, ‘A violência no Brasil: causas e recomendações políticas para a sua prevenção,’ Instituto Nacional de Estudos Demográficos, 1999 Incarcerated, these individuals had the opportunity to interact and establish a structured organization inside the relatively secure prison environment. It was inside the Cândido Mendes prison in Rio de Janeiro city that the country’s first and oldest organized criminal group was created: the Red Command (Comando Vermelho, or CV).13InSight Crime, ‘Red Command,’ 18 May 2018

Criminal groups continued to grow across the country – especially in the state of Rio de Janeiro. In fact, this area was the hotbed of organized crime groups that later spread across the country. While largely criminal in nature, the actions of organized crime groups frequently have wider political consequences, challenging public safety and security.14Estadão, ‘O que é milícia: entenda as origens e como o crime funciona no Brasil,’ 12 May 2020. For more on ACLED coding of political violence in the Brazilian context, see the ACLED Methodology and Coding Decisions around Political Violence and Demonstrations in Brazil. Among the groups regularly engaging in violent activities in Brazil are drug trafficking gangs (facções criminosas or quadrilhas in Portuguese) and police militias (often referred to simply as milícias).

Drug trafficking gangs are criminal groups explicitly involved in the illicit trade of drugs, guns, and other products. Police militias, on the other hand, were first created in Rio de Janeiro state around the end of the 1960s by former and serving police and military officers under the banner of fighting crime and drug trafficking activities. By the end of the 1980s, they evolved into a more organized and structured form. Police militias control territory in Rio de Janeiro, offering the illegal provision of basic services through collecting security fees.15Marianna Simões, ‘”No Rio de Janeiro a milícia não é um poder paralelo. É o Estado”,’ El País, 30 January 2019 Since around the 2010s, violence perpetrated by drug trafficking gangs and police militias has become nearly indistinguishable, as both groups engage in corruption, weapons smuggling, extortion, and extrajudicial killings.16Hudson Corrêa, ‘Como nasceram as narcomilícias,’ O Globo, 7 August 2018; Dom Phillips, ”Lesser evil’: how Brazil’s militias wield terror to seize power from gangs,’ The Guardian, 12 July 2018 Narco militias – police militias who have entered the lucrative narcotics business in Rio de Janeiro since around the 2010s – further increase the contestation of territory and drug markets.

The historically convoluted politics of the state also contribute to the scenario of violence and criminality in Rio de Janeiro. In 2016, the governor declared a ‘state of public calamity’ due to the precarious conditions of the state’s finances following years of high corruption and mismanagement of public resources.17Cristina Boeckel et al., ‘Governo do RJ decreta estado de calamidade pública devido à crise,’ G1, 17 June 2016 Criminal groups saw an opportunity to increase their activity, thanks to ineffective law enforcement and political connections. With the state enduring a severe administrative crisis through the years, it was easier for gangs and militias to advance their agendas and expand territorial control. In light of decaying security levels in the state, the federal government intervened in the state’s autonomy in February 2018. An army general was appointed as a commander with police, military police, firefighters, and prison guards under his control.18Italo Nogueira and Júlia Barbon, ‘Under Federal Intervention, Rio Hits Record Number Of Police Killings In 16 Years,’ Folha de São Paulo, 19 December 2018 Human rights groups, public security analysts, and researchers criticized the measure, claiming civilians could be caught in the middle of more intense confrontations.19Paula Mirgalia, ‘Por que a intervenção federal no RJ não vai funcionar, segundo este especialista,’ Nexo, 18 February 2018

Furthermore, at the start of 2019, the newly-elected Rio de Janeiro Governor Wilson Witzel authorized police officers to use lethal force against criminal suspects.20Anna Jean Kaiser, ‘Rio governor confirms plans for shoot-to-kill policing policy,’ The Guardian, 4 January 2019 His approach to dealing with criminality led to an increase in the lethality of police operations in the region.21Filipe Betim, ‘Sob Witzel, policiais já respondem por quase metade de mortes violentas na região metropolitana do Rio,’ El Pais, 21 August 2019 In February 2019, an armed clash between criminal suspects and military police in the Fallet community ended with 15 suspects reportedly killed. An officer later claimed they shot 82 times inside the house where nine of the suspects were located.22Nicholás Satranio, ‘PMs afirmam ter atirado 82 vezes dentro de casa onde 9 foram baleados no Fallet,’ G1, 6 April 2021 This complex context of criminality in Rio de Janeiro, coupled with aggressive governmental security policies, created a scenario that paved the way for increased deadliness in the state.

Increased Deadliness of Gang and Militia Violence

Between the beginning of ACLED coverage in 2018 and 2022, armed clashes have been responsible for 78% of reported fatalities in Rio de Janeiro state. While the overall number of armed clashes did not change markedly between 2020 – 2,140 events — and 2021 — 2,124 events, the number of armed clashes grew to 2,411 events in 2022. ACLED also records a significant increase in the number of reported fatalities resulting from these clashes. Clashes between gangs and militias were responsible for 28% of reported fatalities and over half of all armed clash events in Rio de Janeiro state in 2021 and 2022. However, clashes involving state forces account for a disproportionately large share of reported fatalities (71%), despite accounting for less than half the number of recorded events.

When police militias and drug trafficking gangs come head-to-head, the resulting clashes are increasingly deadly – accounting for 280 reported fatalities in 2022, up from 218 reported deaths in 2021, reflecting a 28% increase in fatality numbers. The increase in fatalities coincides with a smaller but still significant increase in such clashes: 323 clashes were reported between these groups in 2022, as opposed to 285 such events in 2021.

Clashes between police militias and drug trafficking gangs often revolve around territorial control disputes. Most of the violence takes place in Rio de Janeiro city, notably in the North Zone – where drug trafficking groups have historically controlled territory – and in the West Zone – where police militias are more present. Border areas are usually more affected. In July and August 2022, for example, the CV engaged in several clashes with the Campinho police militia for the control of the Morro do Fubá community in the North Zone, resulting in at least eight people being reportedly killed in separate events throughout the months, including civilians.

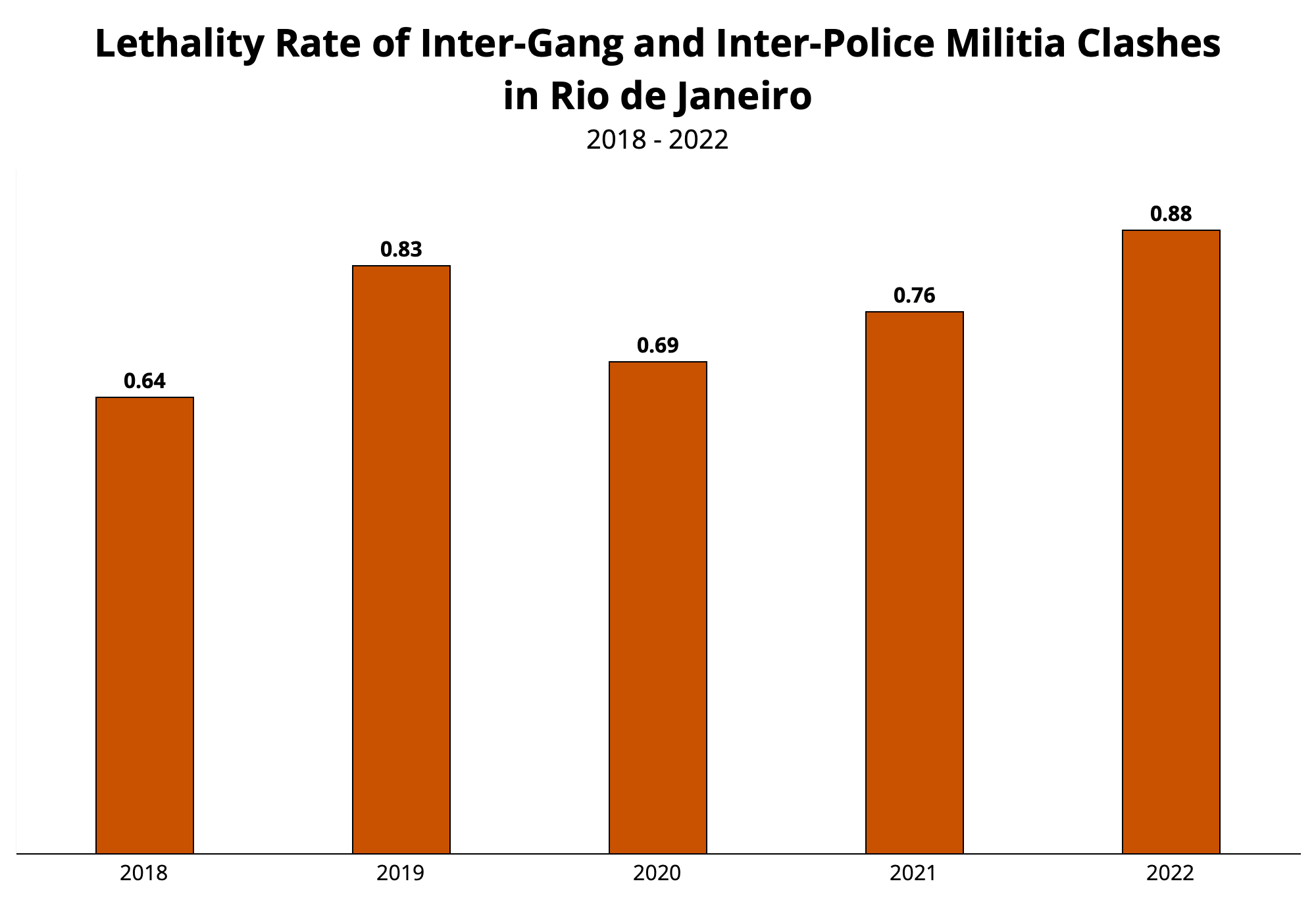

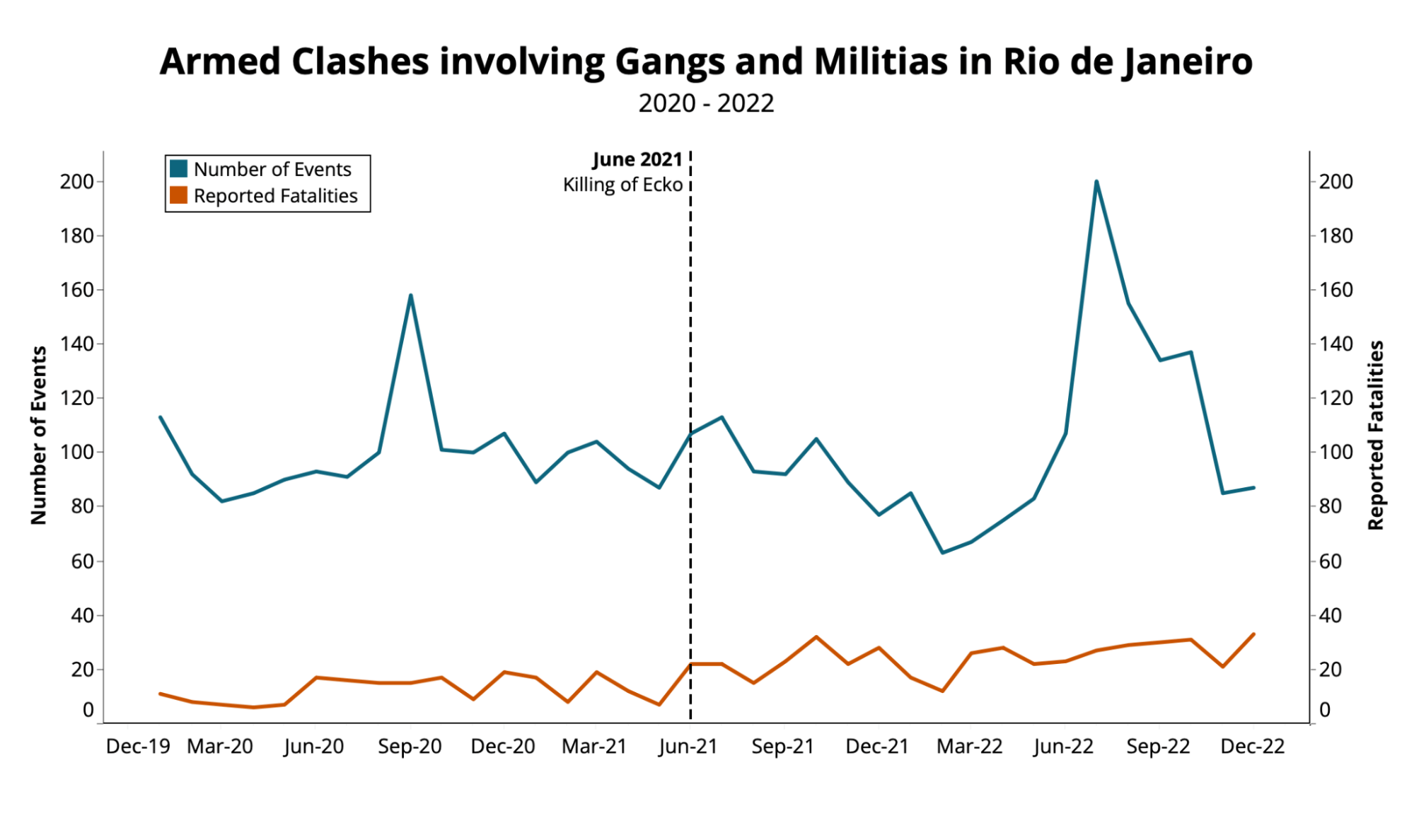

These trends are reflected in the worsening lethality rate, which refers to the average number of reported fatalities per event. In 2022, the lethality rate of inter-gang and inter-police militia clashes skyrocketed to 0.88, compared to 0.76 during 2021 (see graph below). This is the highest rate of lethality since ACLED coverage began in 2018. The higher lethality rate can be partially explained by more intense and aggressive incursions of both gangs and militias to gain territory. Internal police militia disputes have also weakened some groups, creating space for other militias and drug trafficking gangs to take advantage and attack.

Following a relative lull in armed clashes in 2020, territorial disputes between police militias increased following the killing of high-profile militia leader Ecko in June 2021. Wellington da Silva Braga (popularly known as Ecko), the leader of the Bonde do Ecko militia, was killed in a police operation in the Paciência neighborhood of Rio de Janeiro. Formerly operating under the name Justice League (Liga da Justiça, in Portuguese), the group is the oldest and largest militia group in Rio de Janeiro, with widespread control in the city’s West Zone and nearby areas. Since his death, rival militia groups have been contesting control of several areas of Rio de Janeiro and neighboring cities, which can partially account for the rise in reported fatalities and violence involving these groups (see graph below). From January 2021 until Ecko’s death on 12 June, 67 deaths were reported from inter-gang and inter-militia clashes. After Ecko’s death and until the end of that year, 151 deaths were reported. Another possible explanation is the enduring war between rival drug trafficking groups, CV and the Pure Third Command (Terceiro Comando Puro, in Portuguese), which has contributed to increasing violence in the city as the groups constantly enter each other’s territory.

While authorities praised the operation that led to Ecko’s death, militia activities in the region continued unaffected. Recent arrests and several internal disputes inside the militias have also allowed for the expansion of drug trafficking groups in some communities of the West Zone.23Twitter @RjMilicia, 14 June 2022; Twitter @RjMilicia, 26 October 2022 Armed clashes between militias and drug trafficking groups, especially the CV, have become more common in militia-dominated areas.24Twitter @RjMilicia, 20 July 2022 In 2020, at least 17 clashes were reported involving the CV and militias in the West Zone, while at least 31 such clashes took place in 2021 and 28 in 2022.

The Brazilian state’s response to crime usually includes increasing patrols and authorizing stricter policing in vulnerable areas such as Rio de Janeiro state.25Ana Luiza Albuquerque, ‘Pandemia acentuou autoridade de criminosos onde o Estado é ausente, afirma professor,’ Folha de São Paulo, 4 August 2021 Since coming to power in August 2020, Rio de Janeiro Governor Castro has pursued lethal public security policies, continuing the policies of far-right former Governor Witzel, who had claimed he would hire snipers to kill criminals “with a shot in their heads.”26Calo Sartori, ‘Mesmo com queda de mortes, Polícia do Rio é a mais letal,’ Terra, 16 July 2021 Castro was Witzel’s vice-governor, replacing him when Witzel was impeached over corruption schemes and fraud in the acquisition of respirators amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

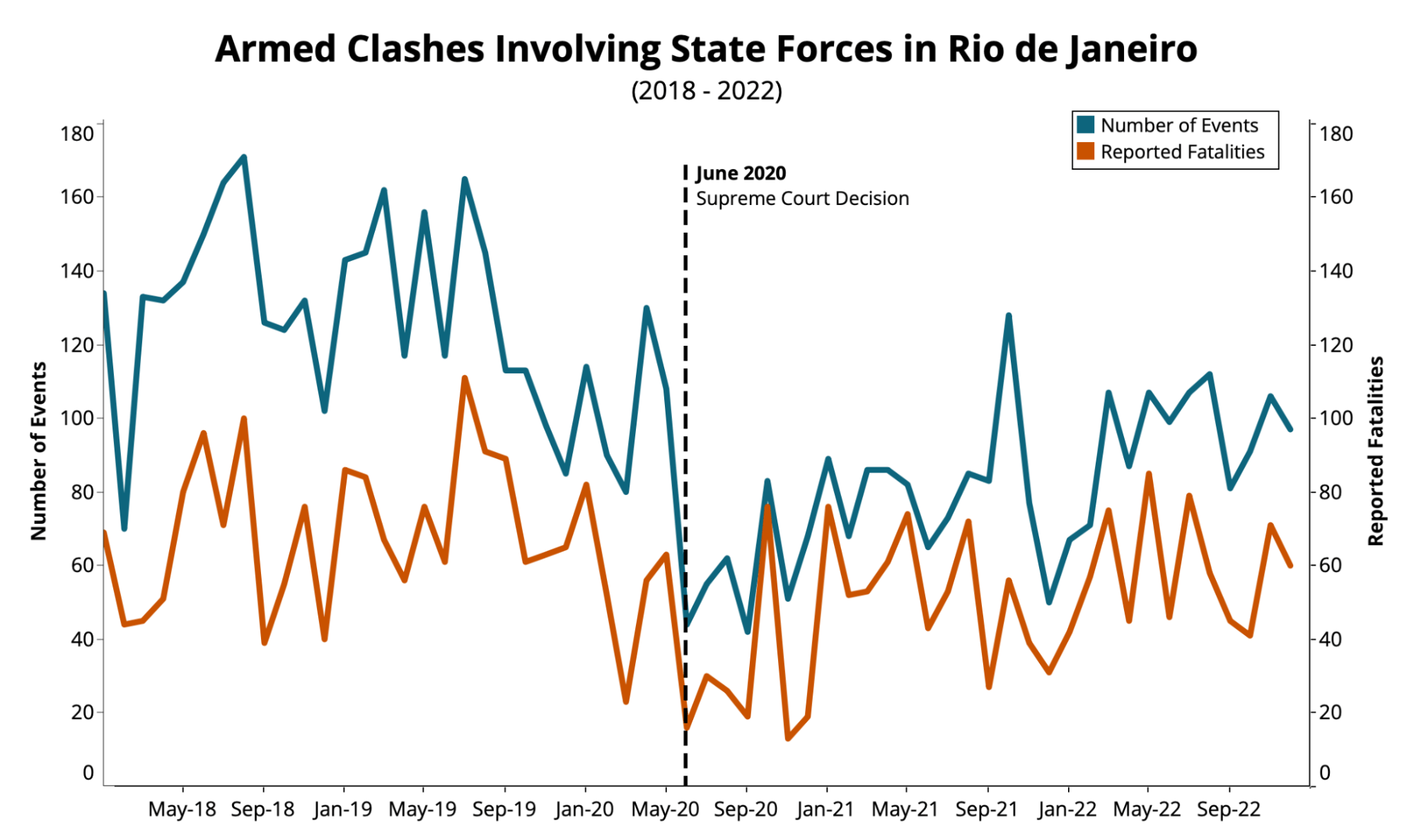

In June 2020, the Supreme Court of Justice ruled to prohibit police operations in the favelas of Rio de Janeiro. This action was an attempt by the court to protect civilians quarantined in violence-affected communities amid the COVID-19 pandemic.27Joāo Pedro Soares, ‘Polícia do Rio ignora STF e aumenta truculência em operações,’ DW, 12 March 2021 While the operations were initially suspended, state forces stopped respecting the measure and police operations increased again in September 2020,28Bárbara Carvalho and Fabiana Cimieri, ‘Favelas do RJ têm quase 800 mortos em ações policiais desde que STF mandou restringir operações,’ G1, 5 April 2021 corresponding with a rise in deadliness in Rio de Janeiro state (see orange on line graph below). Despite the numbers of armed clashes involving state forces only increasing marginally between 2020 — 927 events — and 2021 — 972 events, reported fatalities grew by 34%, from 475 fatalities in 2020 to 637 in 2021. In 2022, ACLED records 1,132 armed clashes, resulting in 704 reported fatalities – an increase of 16% in the number of events and an 11% increase in the number of fatalities, when compared to 2021 (see teal on line graph below).

While armed clashes involving state forces have yet to reach their pre-pandemic heights, operations by state forces in 2021 and 2022 have been noteworthy for their lethality in the city. Since the beginning of 2021, ACLED records some of the deadliest state force operations in Rio de Janeiro’s history, including the May 2021 Jacarezinho and May 2022 Vila Cruzeiro operations. In July 2022, a civil and military police raid in the Alemão Complex community left numerous people dead. According to locals, more than 20 people were killed in the raid, while state forces confirmed 18 deaths.

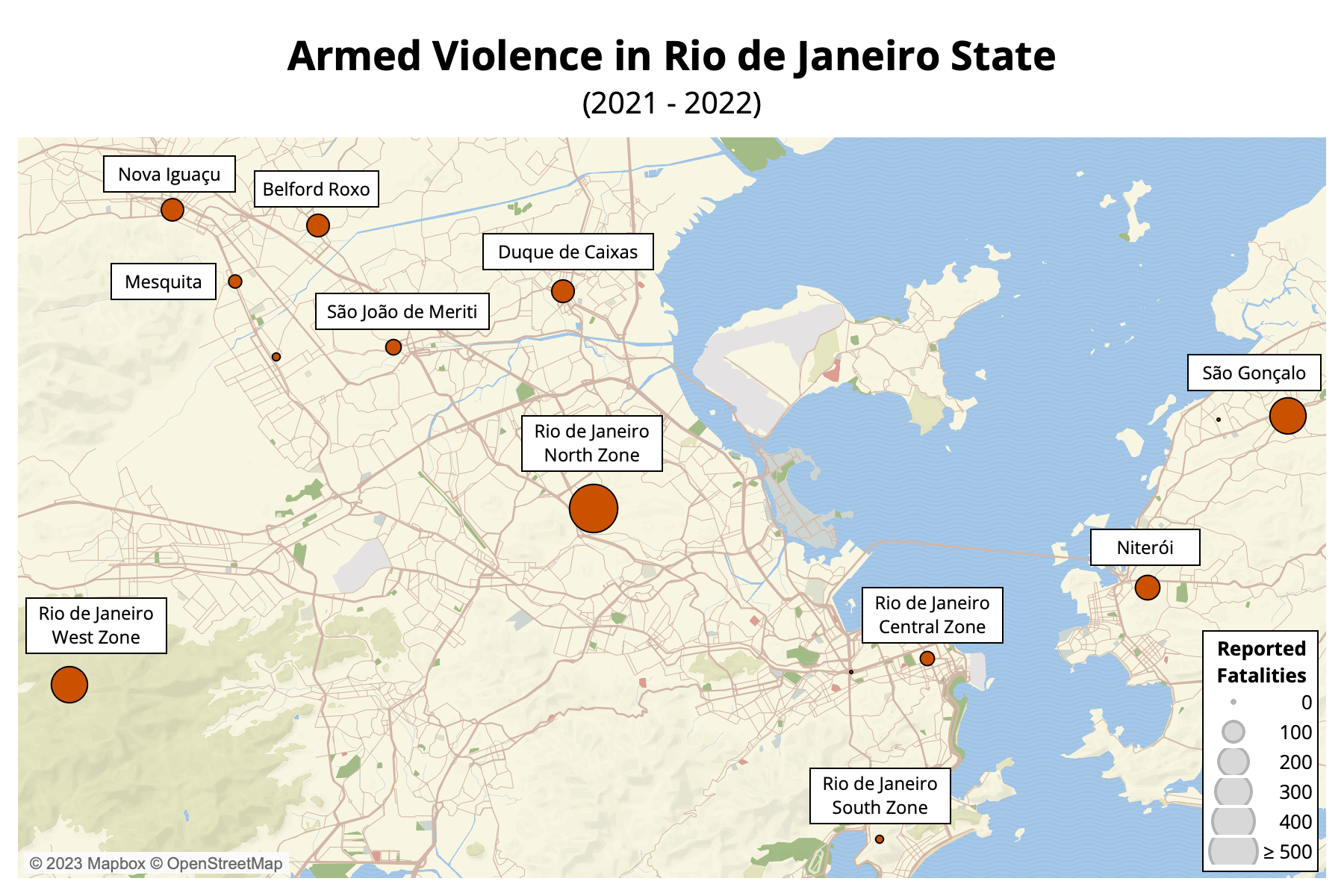

Violence is not only confined to Rio de Janeiro city within the state; it often spills over to the surrounding metropolitan area where criminal groups also exert control and often engage in heavy fighting not only with each other but also with state forces. The city of São Gonçalo comes after Rio de Janeiro city as the deadliest city in the state in 2021 and 2022, with 279 reported fatalities, followed by Niterói, Duque de Caxias, and Belford Roxo, with 127, 117, and 107 reported fatalities, respectively (see map below).

Increased Violence Targeting Civilians

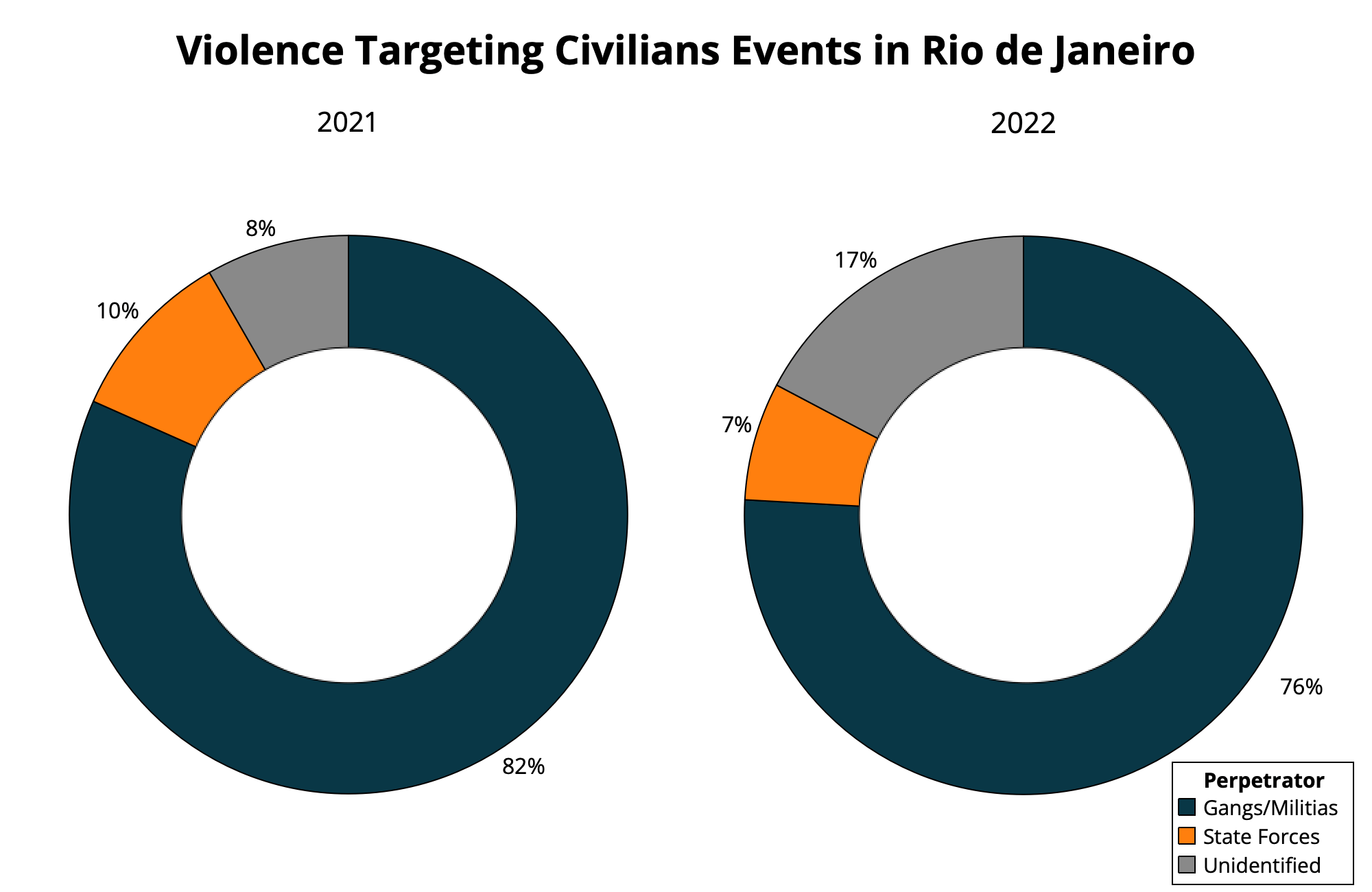

As of 2021, more than 4.4 million people in Rio de Janeiro state were living in areas dominated by organized crime groups, with two million in CV-controlled areas and 2.7 million in militia-controlled areas.29Grupo de Estudos dos Novos Illegalismos and Fogo Cruzado ‘Mapa dos Grupos Armados do Rio de Janeiro,’ Universidade Federal Fluminense, September 2022 Civilians often bear the brunt of violence as criminal groups dispute control of favelas and neighborhoods, and state forces engage in operations to battle these groups. In 2022, ACLED records 338 violent events targeting civilians in Rio de Janeiro state, with 258 reported fatalities. These figures are reflective of two years of consecutive growth. Events where civilians were targeted increased by 17% in 2021 compared to 2020, with reported fatalities increasing by 44%. In 2022, events increased by 48% compared to 2021, with fatalities increasing by 26%. While both state forces and organized criminal groups targeted civilians, the latter were responsible for the most violence, accounting for 82% of violent events targeting civilians in 2021 and 76% in 2022 (see pie chart below).

In 2022, ACLED records the reported deaths of at least 212 civilians in targeted attacks perpetrated by drug trafficking gangs or police militias, compared to at least 106 reported fatalities in 2020 and 174 in 2021. The majority of events recorded by ACLED are attributed to unidentified groups. In some cases, the perpetrators are indeed unknown; however, major media broadcasters in Brazil tend to not report the name of organized criminal groups even when they are confirmed to be perpetrators. This controversial journalistic practice allegedly aims to avoid displaying the real power of the groups, although this omission is criticized by analysts and local communities.30Raissa Melo, ‘O medo da imprensa em noticiar o nome das facções do tráfico,’ Agência de Notícias das Favelas, 29 August 2020 Gangs and militias have occasionally engaged in political killings, such as when a police militia reportedly killed City Councilwoman Marielle Franco and her driver in Rio de Janeiro city in March 2018. Franco, a Black LGBT+ woman, was actively involved in investigations targeting police militias in the city.31Sérgio Ramalho and Marina Lang, ‘Contatinhos Perigosos,’ The Intercept Brasil, 22 June 2020

Moreover, civilians who cooperate in investigations into organized criminal activity are vulnerable to being targeted by these groups. For example, on 3 May 2021, armed men on motorcycles shot and reportedly killed five people standing in front of a bar in Mesquita city. Three people were also injured in the event, which took place in a neighborhood dominated by a police militia. One of the victims had been a witness in a 2015 inquiry led by the Baixada Fluminense homicide police station into police militia activity, in which he testified against a militia regarding their drug trafficking activity.32Thuany Dossares, ‘Chacina de Mesquita: uma das vítimas foi testemunha em inquérito na DHBF,’ O Dia, 5 May 2021 It has not been confirmed that both events were related. However, the incident illustrates that given the lack of adequate protection from government authorities for those who decide to denounce crimes and illegal activities, many locals choose to remain silent. In addition, the links of many organized crime groups, particularly police militias, with state forces and government authorities also intimidate locals against denouncing these groups.

State forces also perpetrated targeted attacks against civilians. In 2021, these attacks led to at least 17 reported civilian fatalities, up from 13 in 2020. In 2022, ACLED records at least 13 reported civilian fatalities in targeted attacks perpetrated by state forces. Residents of poor communities, often Black people, continued to be most affected by the deadliness of violence in the city. Police and military forces have also accused civilians of being drug suspects and criminals to justify attacks against them. Many of the victims are young Black working-class men from poor communities with no involvement in criminal activities. On 25 April 2022, military police officers reportedly shot a Black man in the chest, killing him. The incident happened in the Jacarezinho community, and witnesses saw the officers running away after firing at the victim. Human rights groups and the victim’s family’s lawyer called for a separate investigation that does not involve the police.33Beatriz Perez, ‘Caso Jonathan: advogado quer investigação independente de morte de jovem no Jacarezinho,’ O Dia, 27 April 2022 In another notable incident, on 6 May 2022, military police officers shot and killed a young Black man with an intellectual disability in Barreira do Vasco community in Rio de Janeiro city. While police claimed the man resisted the officers, this version was denied by witnesses and family members, who claimed no shoot-out or police operation against organized crime groups was taking place at that time.34Jacqueline Cardiano, ‘’Eu quero justiça’ diz irmã de jovem com deficiência intelectual, morto pela PM na Barreira do Vasco,’ Voz das Comunidades, 7 May 2022

The Brazilian Elections and the Future of Violence in Rio

Events with high fatality counts continue to take place in the state, a sign that the 2021 and 2022 trends are likely to continue. Reported fatalities stemming from political violence events surpassed 1,000 in both 2021 and 2022. Clashes involving state forces account for a disproportionately large share of reported fatalities, while inter-gang and inter-militia clashes also remain highly lethal. In addition, ACLED records hundreds of deaths from targeted attacks on civilians in Rio de Janeiro state in 2022. Poor communities, Black people, and civilians involved in investigations against militias and gangs are shown to be particularly vulnerable to targeted violence.

The results of the recent presidential and gubernatorial elections carry the potential to either change or reinforce the existing dynamics of violence and public security in Rio de Janeiro (for more on violence during the 2022 General Elections in Brazil, see ACLED pre- and post-election reports). At the federal level, President Lula claimed he would reinstate the Ministry of Public Security to create coordinated actions with the state governors to fight organized crime, drug trafficking, and weapons smuggling.35Lucas Neiva, ‘LULA REFORÇA RECRIAÇÃO DE MINISTÉRIO DA SEGURANÇA PÚBLICA,’ Congresso em Foco, 25 October 2022 The Ministry of Public Security was first dismembered from the Ministry of Justice by former President Michel Temer during the 2018 military intervention in Rio de Janeiro.36Guilherme Mazui, Bernardo Caram, & Roniara Castilhos, ‘Temer assina decreto de intervenção federal na segurança do Rio de Janeiro,’ G1, 16 February 2018 On 9 December, however, Lula broke his campaign promise and announced the Public Security agenda will continue under the Ministry of Justice, with the name of the institution changing to ‘Ministry of Justice and Public Security.’37Cecília Olliveira, ‘Atos terroristas mostram que Ministério da Justiça e Segurança Pública terá enorme desafio no governo Lula,’ The Intercept Brasil, 16 December 2022 The new minister chosen by Lula is Senator Flávio Dino, a former judge who has also worked as a congressman and governor of Maranhão state.38Wellington Hanna, ‘Atos terroristas mostram que Ministério da Justiça e Segurança Pública terá enorme desafio no governo Lula,’ G1, 9 December 2022

In his inauguration speech on 2 January, Dino said that the government will act to make sure that the culprits of the killing of Councilwoman Marielle are found, indicating that the ministry will advance investigations on police militia activities. In a step that recognizes the importance of the resolution of the crime to Brazil, Lula has chosen Anielle Franco — a journalist, recognized activist, and Marielle’s sister — as his new minister of racial equality. Dino has also pointed out that his ministry will work to implement responsible gun control and measures to decrease lethal and violent crimes, apart from working on the decapitalization of criminal organizations to obstruct their finances.39Folha de São Paulo, ‘Flávio Dino assume Justiça, dá recados a bolsonaristas e fala em federalizar caso Marielle,’ 2 January 2023 Analysts have indicated the need for Dino to go beyond only revoking decrees, for example by working on strengthening inspection authorities.40Marcelo Rocha, ‘Especialistas cobram que Dino vá além de ‘revogaço’ de decretos sobre armas,’ Folha de São Paulo, 25 December 2022

At the state level, Castro’s re-election as state governor in the first round with over 58% of the votes was a surprise to many. Polls leading up to election day had indicated there was a chance Castro would face leftist Marcelo Freixo in a runoff.41G1, ‘Datafolha no RJ: Castro, com 26%, e Freixo, com 23%, estão tecnicamente empatados,’ 17 August 2022 While Castro is a member of former President Bolsonaro’s far-right Liberal Party, he promptly made a phone call to Lula following the election’s official results, indicating political openness.42Lucas Vettorazzo, ‘Como foi a primeira conversa de Lula e Cláudio Castro,’ Veja, 1 November 2022 During the call, Castro congratulated Lula on his victory and said he was available to work together with the federal government. He was sworn in on 1 January 2023, without mentioning Lula or Bolsonaro during his inauguration speech. It remains to be seen if the governor will continue to endorse increasingly invasive police operations to curb violence or if he will follow the Lula’s government in a coordinated federal approach. Lula and Dino’s relationship with Castro will likely have a crucial impact on the complex scenario of increasing deadliness in the state.

ACLED wishes to thank Fogo Cruzado for sharing data on armed violence in Brazil and for providing feedback on earlier drafts of this report. ACLED is solely responsible for any mistakes or inaccuracies.

Visuals in this report were produced by Ana Marco