Political Violence and the 2023 Nigerian Election

22 February 2023

On 25 February 2023, Nigerians will elect a new president, vice president, and members of the National Assembly. Term limit legislation bars President Muhammadu Buhari from running for a third term, and the end of his presidency marks the longest democratic stretch since independence. Eighteen candidates are vying for the presidency, and at least 4,223 candidates are running for the 469 seats in the National Assembly.1Chuks Okocha, ‘INEC Releases Final List of Presidential, National Assembly Candidates for Polls,’ This Day Live, 9 January 2023 The presidential frontrunners include Bola Ahmed Tinubu of the incumbent All Progressives Congress (APC), Atiku Abubakar of the Peoples Democratic Party (PDP), and Peter Obi, the Labour Party (LP) candidate who has surprisingly led in the pre-election polls. Two weeks after the national election, on 11 March 2023, 28 out of 36 states will also elect a new governor, with 17 incumbent governors reaching their term limits and hence barred from re-running.

The 2023 Nigerian elections are, therefore, a watershed moment in the country’s democratic history, opening up competition for federal and state legislative positions to a wide array of candidates without a designated incumbent for those roles. The electoral contest, however, takes place against the backdrop of fierce tensions between political parties and a series of overlapping security crises that affect all regions across Nigeria and the regular conduct of elections. Candidates, election officials, and politicians have been violently targeted in the run-up to the elections. Party militias, criminal gangs, and other armed groups have engaged in violence to suppress opponents, deter rival candidates from running, and influence the electoral process. The electoral campaign has also further polarized the political and media environment, with numerous allegations against partisan outlets and political candidates refusing to attend media engagements.2Bakare Majeed, ‘2023: Arise TV, This Day accuse Tinubu’s campaign of requesting sack of journalists over ‘unfavourable reportage’,’ Premium Times, 12 December 2022; Adedayo Akinwale, ‘Tinubu’s Avoidance of Media Engagements,’ This Day Live, 18 December 2022 Some candidates are accused of inciting hate speech and stoking inter-communal tensions, at risk of escalating violence in a country with a long history of electoral violence since its independence in 1960.3Samuel Oyewole, ‘There’s violence every election season in Nigeria: what can be done to stop it,’ The Conversation, 7 June 2022

Since the beginning of the electoral campaign, ACLED has monitored the impact and dynamics of political violence in Nigeria through the Nigeria Election Violence Tracker, an interactive resource created in partnership with the Nigeria-based Centre for Democracy & Development (CDD). This report finds that political violence in the run-up to the 2023 election is largely in line with the levels observed before the 2019 election, increasing close to the election date. Yet, rising violence targeting party supporters and electoral officials, as well as activity by regional and criminal groups, point to possible vulnerabilities in the aftermath of the vote. This report assesses three patterns of election violence: the impact of violence between party supporters and against candidates; attacks on Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) offices and staff; and the involvement of regional security outfits and criminal gangs. In the concluding section, the report identifies the risks of further violent escalation in the aftermath of the elections.

A Long History of Party Violence

The electoral process in Nigeria has coincided with a surge in violent events involving political parties, with the movement to democratic rule followed by spikes of additional insecurity every four years. Violent incidents carried out by and against supporters of political parties have spiked each election year since 1999 around national and state elections. During previous election cycles, partisan violence has escalated along ethnic and sectarian lines, resulting in multiple rounds of revenge killings. The magnitude of electoral unrest was recorded at its highest in 2011 when clashes between supporters of the then-ruling PDP and the Congress for Progressive Change – which later merged into the APC – claimed an estimated 800 lives following the election of President Goodluck Jonathan.4Human Rights Watch, ‘Nigeria: Post-Election Violence Killed 800,’ 16 May 2011 Likewise, hundreds are reported to have died during the following elections in 2015 and 2019.5Kunle Adebajo, ‘Nigeria’s Deadly History Of Electoral Violence In Five Charts,’ HumAngle, 27 June 2022

Ahead of the 2023 polls, candidates and leaders of 18 political parties agreed in September 2022 to sign a peace accord committing to a peaceful campaign. According to the leader of the National Peace Committee, the accord calls on all parties to refrain from using “violence, incitement and personal insults” against opponents, which has marred electoral campaigns in recent years.6Chinedu Asadu, ‘Nigerian presidential hopefuls sign election peace accord,’ Associated Press, 29 September 2022 Politicians, including agents of the state, have often been held responsible for promoting hate speech against rival candidates and ethnic and religious communities.7Centre for Democracy and Development, ‘Sorting Fact From Fiction: Nigeria’s 2019 Election,’ 26 July 2019 In turn, the mobilization of armed militias, gangs, and state security forces at the behest of local elites is intended to depress voter turnout and maximize vote shares in key battleground constituencies.8Samuel Oyewole, ‘There’s violence every election season in Nigeria: what can be done to stop it,’ The Conversation, 7 June 2022; Ray Ekpu, ‘Unknown gunmen and the elections,’ The Guardian (Nigeria), 24 January 2023

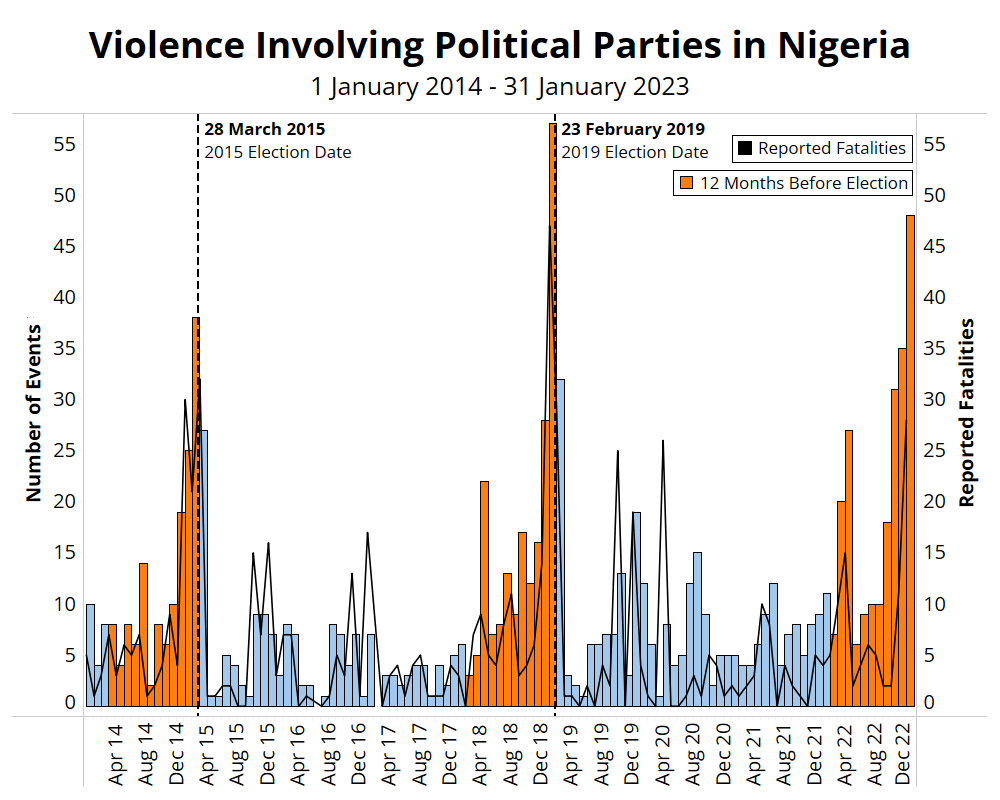

In the 12 months preceding the election, ACLED records over 200 violent events involving party members and supporters, resulting in nearly 100 reported fatalities. These numbers are largely in line with the run-ups to the previous two election years, with over 150 events and more than 100 reported fatalities between 2018 and 2019, and an estimated 115 events and over 90 fatalities between 2014 and 2015 (see graph below). The South East (46 events) and the South West (45) registered the highest number of violent events involving party supporters before the 2023 election, followed by the South South (38) and North Central (32) areas. Nearly one in 10 events took place in the battleground state of Osun, where both the PDP and APC have traded allegations over inciting violence against their rivals.9Abdulqudus Ogundapo, ‘Video: PDP leader threatens political violence in Osun ahead of elections,’ Premium Times, 10 February 2023; Francis Ezediuno, ‘Osun: PDP accuses APC of increasing attacks on its members,’ Daily Post, 11 February 2023 Half of the violence involving party supporters in the 12 months before the 2023 election involves direct, organized attacks against civilians, followed by mob violence and abductions.

Unarmed civilians were the target of violence in around 80% of the events recorded by ACLED, accounting for approximately 75 of the nearly 100 reported fatalities arising from events between February 2022 and February 2023. Attacks against prospective candidates, party supporters, and local apparatchiks were a common occurrence during this period, including in areas where Nigeria’s overlapping security crises exacerbate threats to the physical security of politicians. In one such case, gunmen described as “bandits” killed an APC ward chairman in Kaduna state in April 2022.10Ibrahim Hassan-Wuyo, ‘Bandits kill APC ward chair, others in Kaduna,’ Vanguard, 27 April 2022 For the most part, however, these attacks remain unclaimed. Unidentified armed groups were responsible for at least half of all violence against party members in the run-up to the vote, suggesting that the perpetrators of this violence can often act with impunity.

Members and candidates of Nigeria’s biggest political parties – the APC and PDP – were among the most frequent targets of this violence. In one of the deadliest reported incidents thus far, the PDP candidate for Ideato North and South federal constituency in Imo state was killed in his residence in Akokwa community in January 2023.11Udora Orizu, ‘Gunmen Attack CUPP Spokesman’s House in Imo, Unknown Number of Persons Reportedly Killed,’ This Day Live, 14 January 2023 In some cases, women politicians were the victims of electoral violence. A former PDP leader in Abia state was among four people killed in Ohafia Local Government Area (LGA) in March 2022,12Sunday Nwakanma, ‘Gunmen kill ex-PDP women leader, daughter, two others in Abia,’ Punch Nigeria, 3 March 2022 while an LP leader in Kaura LGA of Kaduna state was murdered in November after gunmen raided her house.13Vanguard, ‘How gunmen killed Labour Party LGA women leader in Kaduna,’ 30 November 2022

Special Focus on Battleground States: Kano

Nigeria’s North West has turned into a hotbed of violence as armed groups engaging in kidnappings, cattle rustling, and retaliatory killings – commonly referred to as bandits – escalated their activity. Rural banditry has intensified against the backdrop of ongoing tensions between Fulani pastoralists and Hausa farmers that extend to the Middle Belt region, often leading to mobilization along ethnic and religious lines. Amid a volatile conflict environment, federal and state government officials cited the heightened violence as the reason for interdictions of political campaigning in some LGAs.14Daily Trust, ‘Zamfara Lifts Ban On Political Rallies, Reopens Markets, Schools In 3 Affected LGAs,’ 25 October 2022 Within the region, electoral violence was highest in Kano, where tensions between and within parties have occasionally turned deadly. In November 2022, supporters of the New Nigeria Peoples Party (NNPP) and the APC clashed in Gwale LGA, as both sides accused each other of instigating violence.15Rahima Shehu Dokaji, ‘Tension Between APC, NNPP Supporters Threatens 2023 Elections In Kano,’ Daily Trust, 11 December 2022 Earlier in the year, fighting broke out in March between supporters of rival candidates in the gubernatorial APC primaries in Rano LGA, with heavy clashes resulting in at least one person killed.16Abubakar Ahmadu Maishanu, ‘2023: Kano will not tolerate violence during campaign – Ganduje,’ Premium Times, 21 November 2022 Kano is home to NNPP presidential candidate Rabiu Kwankwaso, while Kano governor Abdullahi Ganduje is a close ally of APC candidate Bola Tinubu.17International Crisis Group, ‘Countdown Begins to Nigeria’s Crucial 2023 Elections,’ 23 December 2022 In 2019, Muhammadu Buhari secured a landslide victory in Kano.

Electoral Staff Under Attack

Nigeria’s INEC is responsible for organizing, conducting, and supervising elections, as well as registering eligible voters and political parties, and overseeing electoral spending. Election management bodies in Nigeria have long been the subject of criticism over corruption, bias, irregularities, and mismanagement.18Osita Agbu (ed.), ‘Elections and Governance in Nigeria’s Fourth Republic,’ Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa, 2016 Against the backdrop of widespread insecurity, INEC has a crucial role in ensuring the regular conduct of elections. In the years leading up to the 2023 elections, INEC offices across the country have been subject to looting, arson attacks, and shootings, as well as abductions and assassinations of electoral officers.

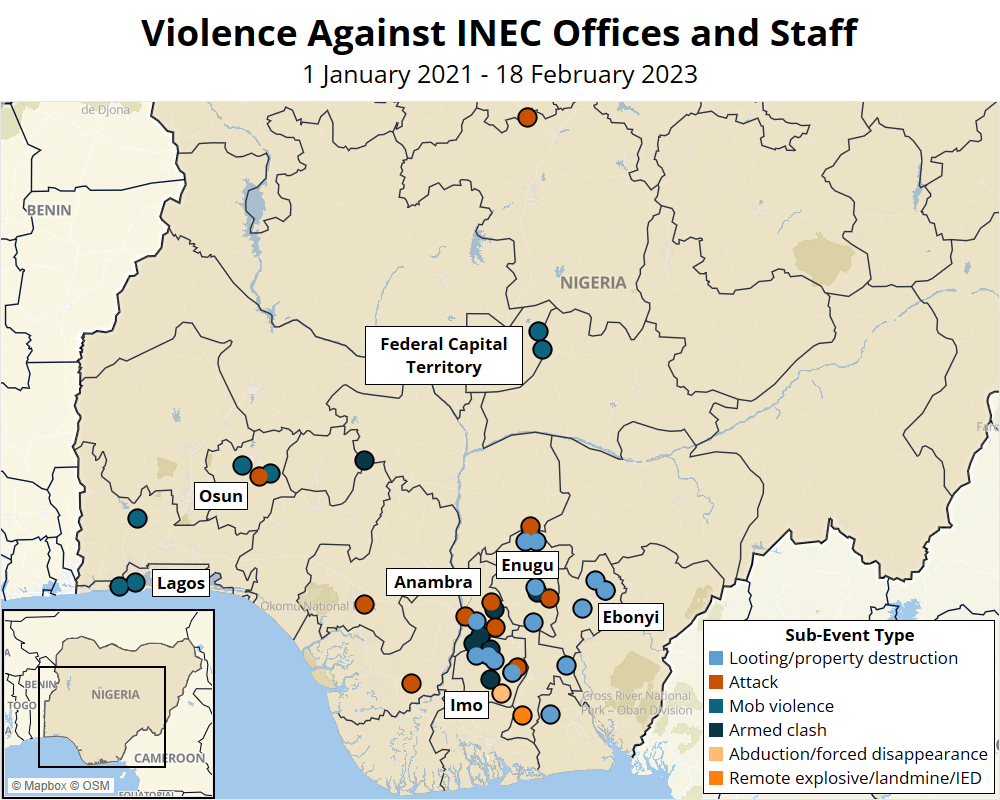

Between January 2021 and February 2023, ACLED records 44 violent incidents involving INEC offices and staff. The frequency of these incidents in the 12 months before the 2023 election (23 events) is higher than during the same period between 2018 and 2019 (11 events), before a post-2019 election spike, with more than 40 events recorded between February and March 2019 alone. The late spike in violence targeting INEC offices and staff in 2019 shows the potential for violence following the 2023 elections and into the gubernatorial voting period. Polling stations in central and southern Nigeria were also targeted during the #EndSARS demonstrations, the youth-led movement that spread across the country in 2020 calling for an end to police brutality and the disbandment of the Special Anti-Robbery Squad.

The South East accounts for the largest share of violence against INEC offices and staff in the run-up to the 2023 elections. Over two-thirds of the total events recorded between 2021 and 2022 were in the southeastern states, especially in Imo, Enugu, and Anambra (see map below). Nigerian police have blamed recent attacks targeting polling stations and INEC staff in the South East on the Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB) and its militant wing, the Eastern Security Network (ESN), allegations denied by the secessionist group leaders.19Kunle Daramola, ‘“We’re uninterested in 2023 polls” — IPOB denies involvement in attack on INEC office,’ The Cable, 5 December 2022 Although continuing to take a critical position towards the elections and expressing ongoing demands for an independent Biafra, IPOB stated that the group would not issue sit-in orders or enforce a boycott of the elections on the local populations.20Nurudeen Shotayo, ‘2023: IPOB suspends sit-at-home for elections,’ Pulse, 2 February 2023 Elevating tensions, the government also refused to release Nnamdi Kanu, the secessionist IPOB leader arrested in Kenya in 2021, with numerous demonstrations for his release held during the pre-election period.21Sahara Reporters, ‘Nnamdi Kanu’s Lawyer Gives Update On Appeal Against Nigerian Government Before Supreme Court,’ 19 January 2023 While IPOB tends to receive the blame for violence against INEC offices and staff in the South East, several protests by voters in Enugu and Anambra against perceived problems with INEC operations, alongside mobs and unidentified gunmen ransacking election offices, may reveal wider discontent with the electoral process.

As in the South East, the broader security context has shaped violence against INEC staff and offices in other regions. In the context of ongoing Islamist insurgency in the North East and escalating militia violence in the North West, INEC offices have occasionally been vandalized by jihadists and bandits in Borno and Kaduna states, respectively. In the southern states, political violence often involves political elites or parties with links to unidentified gunmen, criminal groups, and cult militias. An unknown armed group attacked INEC collection centers in Ikpoba Okha LGA in Edo state on two occasions in January 2023. During the first attack, the militants disrupted the distribution of INEC Permanent Voters Cards. Further, violence against INEC staff and the thwarting of operations in July 2022 led to voting disruptions and some election results being canceled in Osun state, which can benefit certain political actors.

Special Focus on Battleground States: South East

Incidents of election-related violence in states in the South East rose sharply in 2022, more than tripling from the previous year. In the run-up to the elections, violence specifically targeting INEC peaked in the South East, which also accounted for the highest proportion of violent events targeting opposition LP and All Progressives Grand Alliance supporters. LP presidential candidate Peter Obi hails from the South East: the former governor of Anambra state, Obi defected from the PDP to the LP in 2022, and has since attracted considerable support among the younger segments of the Nigerian electorate.22Leena Koni Hoffmann, ‘Whoever wins Nigeria’s election faces a crisis of inclusion,’ Chatham House, 3 February 2023 The region is also home to the separatist insurgency spearheaded by IPOB, which blames the federal government for marginalizing the South East and the ethnic Igbo population. Since the arrest of its leader, Nnamdi Kanu, IPOB has been increasingly active in Anambra, Enugu, and especially Imo. Armed separatists, operating under the banner of the militant ESN organization, have targeted police stations and patrols, including operatives of the Ebubeagu security outfit (see more on this actor below). Igbo elders and Obi’s allies have raised concerns that calls for boycotting the elections and attacks by non-state armed groups may affect voter turnout in the region.23Sahara Reporters, ‘Ignore Those Calling For Boycott Of 2023 Elections —Ex-NADECO Chieftain, Obioha Tells Igbo People,’ 13 February 2023

Other Agents of Electoral Violence: Regional Security Outfits and Criminal Groups

Electoral violence is not limited to political parties and attacks by non-state armed groups. Other violent agents may engage in actions with the objective of interfering with the electoral process and benefitting political elites. These include regional security outfits under the authority of local elites and criminal groups operating in coordination with politicians.

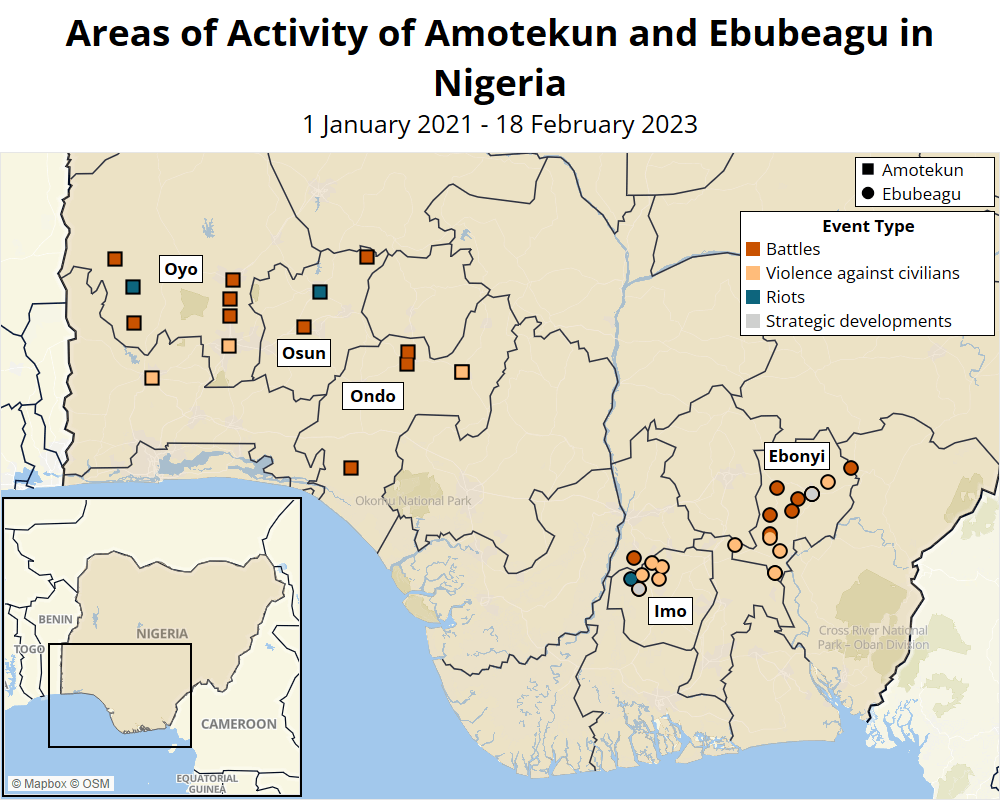

Among the most important regional security outfits created in Nigeria are the Amotekun and the Ebubeagu. In January 2020, the governors of six southwestern states – Ekiti, Lagos, Ogun, Ondo, Osun, and Oyo24Lagos state has not yet established its own Amotekun Corps. See Philip Anjorin, ‘Why Lagos govt has not established Amotekun – Sanwo-Olu,’ Premium Times, 7 June 2021 – established the Western Nigeria Security Network. This network consists of state-sponsored security organizations that assist law enforcement agencies in tackling kidnappings, cattle rustling, violations of anti-grazing laws, and other criminal activities.25Modestus Aneasoronye, ‘Five things you need to know about Operation Amotekun,’ Business Day, 4 March 2020 Codenamed Amotekun Corps, its operatives are largely recruited from among ethnic Yorubas and local vigilante groups.

In a similar fashion, governors of the five ethnic Igbo states in the South East – Abia, Anambra, Ebonyi, Enugu, and Imo – launched the Ebubeagu in April 2021. Its creation was prompted by widespread insecurity due to kidnappings, secessionist insurgencies, armed banditry, and communal conflicts across the South East. Unlike in the South West, however, political factionalism has prevented the southeastern governors from creating a network of state-sponsored security agencies like with the Amotekun. The Ebubeagu’s activity also partially overlaps with that of local vigilante organizations, resulting in a duplication of security spending and a controversial legal status.26Ben Nwosu and Ndu Nwokolo, ‘Ebubeagu Regional Security Outfit in South-East Nigeria: Reasons for the Discontents,’ Nextier, 22 September 2022

The establishment of regional security outfits consisting of locally recruited operatives has gained some acceptance among local populations in the face of rampant insecurity.27Oluwatobi Odeyinka, ‘Insecurity: How Amotekun Is Faring In Southwest Nigeria 20 Months After Inauguration,’ HumAngle, 2 September 2021 Yet, some segments of Nigeria’s political elite have expressed opposition to these armed groups. Northern leaders and APC governors rejected the Amotekun, claiming that it was created outside the law and that it exacerbates communal tensions.28James Kwen, ‘APC northern governors reject Amotekun, back community policing,’ Business Day, 24 January 2020; Taiwo Adebulu, ‘Northern elders: Amotekun is not the solution to insecurity,’ The Cable, 25 January 2021 The governor of Ondo state, meanwhile, accused the federal government of failing to provide adequate weapons to the Amotekun while instead enabling northern vigilante groups to do so.29Josiah Oluwole, ‘Insecurity: Akeredolu vows to acquire weapons for Amotekun, blasts FG on double standards,’ Premium Times, 22 September 2022 Behind this backlash, there are concerns that the regional security outfits established in the south could target other ethnic groups, including the Fulanis, and enjoy impunity from alleged human rights violations.30Oluwatobi Odeyinka, ‘Insecurity: How Amotekun Is Faring In Southwest Nigeria 20 Months After Inauguration,’ HumAngle, 2 September 2021 Both the Amotekun and Ebubeagu have been linked to multiple abuses, torture, and extrajudicial killings since their creation.31Sahara Reporters, ‘Amnesty International, Activists Raise Concerns As Amotekun Kills 11 In Three Weeks,’ 16 January 2021; Vanguard, ‘Extrajudicial executions by Ebubeagu under guise of tackling insecurity in S-East must stop – Amnesty International,’ 20 July 2022 At least 15 cases of violence against civilians involving the two groups were reported between January 2021 and February 2023, including 12 attributed to the Ebubeagu and three to the Amotekun (see map below).

The groups’ activity has come under scrutiny, especially in the run-up to the elections. A report by international election watchdogs warned in December 2022 that the “proliferation of informal security elements – such as Amotekun in the South West and Ebubeagu in the South East – further complicates security and increases opportunities for election violence and malfeasance.”32International Republican Institute and National Democratic Institute, ‘Statement of the Second Joint NDI/IRI Pre-Election Assessment Mission to Nigeria’, 9 December 2022 In September 2022, the Nigerian police chief assuaged fears over the political use of regional security outfits, stating that the Amotekun and Ebubeagu would not be deployed to election rallies.33Nigerian Tribune, ‘2023: IGP bans use of Amotekun, ESN, other local security outfits for campaigns,’ 22 September 2022 Nevertheless, rights groups accused the Ebubeagu of operating as a personal militia for the APC governor of Ebonyi state, David Umahi.34Dennis Agbo, ‘Ebonyi Group bemoans use of Ebubeagu against opposition candidates,’ Vanguard, 19 October 2022 Opposition parties reported that their candidates in Ebonyi were subjected to intimidation, unlawful abductions, and torture at the hands of the Ebubeagu.35Peoples Gazette, ‘2023: APGA guber candidate Odoh accuses Ebubeagu of attacking convoy,’ 21 October 2022; James Eze, ‘Ebubeagu abducts, tortures Ebonyi PDP candidate’s spokesperson,’ Premium Times, 10 November 2022 A federal court in Ebonyi eventually ordered the disbanding of the Ebubeagu in February 2023 due to its involvement in extrajudicial activities.36Peter Okutu, ‘Breaking: Court disbands Ebubeagu security outfit,’ Vanguard, 14 February 2023

Special Focus on Battleground States: Osun

Amid heightened factional APC and PDP infighting, violence has escalated in the South West, which accounts for the most violence involving political parties. Civil society groups warn that, within the South West, Osun state presents the highest risk of political violence in the run-up to the elections.37Francis Ezediuno, ‘Worries as Osun tops list of politically violent States,’ Daily Post, 17 January 2023 Destruction of party billboards, harassment of candidates, attacks on party offices, and frequent incidents of mob violence attest to the fierce political competition in what is considered an electoral battleground. President Buhari won the state by just over 1% in 2019, while PDP candidate Ademola Adeleke unseated the APC incumbent governor by over 3% in the 2022 gubernatorial elections. The APC itself has become deeply divided following attempts by former governor Alhaji Gboyega Oyetola and current Interior Minister Rauf Aregbesola to split the party.38James Ogunnaike, ‘Aftermath of Osun election: APC must embrace genuine reconciliation ahead 2023 — Party Chieftain,’ Vanguard, 25 July 2022 APC infighting has also turned violent on several occasions, including in the state capital Osogbo, as supporters of opposing factions engaged in fighting.39Gbenga Faturoti, ‘Gunmen Attack Aregbesola’s Campaign Office In Osogbo,’ Independent, 4 February 2022 In January 2023, a state tribunal overturned the July 2022 Osun gubernatorial election that handed the state over to the PDP, increasing the risk of fresh violence in the state.

In addition to the involvement of regional security outfits, there are also concerns that local elites could hire criminal gangs and militias to inflict violence on political opponents. In August 2022, Rivers Governor Nyesom Wike stirred controversy when he warned that political parties and candidates were enlisting hired arms to inflict “mayhem, thuggery or violence” ahead of the elections in his state.40Okafor Ofiebor, ‘2023: Wike alleges plot to cause mayhem in Rivers, warns hotel owners,’ PM News, 7 August 2022 Yet, the recruitment of gangs for electoral purposes has a long history in Nigerian politics, with reports of criminal groups being hired to intimidate voters, attack their patrons’ rivals, or protect politicians in previous elections.41Human Rights Watch, ‘Criminal Politics: Violence, ‘Godfathers’ and Corruption in Nigeria,’ October 2007 Among these gangs-for-hire are also cult groups and student confraternities based out of university campuses. Cults are involved in a web of criminal activities, including extortion and human and drug trafficking, frequently clashing with other criminal organizations and waging attacks against former or other group members. They include groups such as the Black Axe, Eiye, Icelanders, Greenlanders, and Vikings. Some politicians are reported to have links with cult groups, especially in southern Nigeria, where most cults are based.42Sahara Reporters, ‘Christian Association, CAN Directs Churches In Nigeria To Vote Against Presidential Candidates With Links To Drugs, Boko Haram,’ 19 July 2022 Between January 2022 and February 2023, ACLED records 175 violent events involving cult militias, resulting in nearly 280 reported fatalities. Lagos state accounts for approximately 20% of all events recorded by ACLED during this period, followed by other southern states like Ogun, Osun, and Delta. Cult militias have also been reported across Nigeria, including in some central states such as Kwara, Benue, Kogi, and Plateau.

Conclusion

Nigeria’s 2023 elections are historic. Never before has the country experienced a longer period of uninterrupted democratic governance. The peaceful transfer of power from Buhari to his successor will be a remarkable milestone in a continent still marked by the recurrence of military coups – a feature that has long characterized Nigeria’s history after independence.43Peter Mwai, ‘Are military takeovers on the rise in Africa?,’ BBC, 4 January 2023 Yet, Nigeria’s political and security crises – a combination of jihadist insurgencies, rural banditry, communal conflicts, and separatist campaigns – threaten the prospects of holding free and fair elections nationwide, heightening the risk of yet another violent escalation in the aftermath of the elections.

Electoral violence shapes, and is shaped by, the surrounding political environment. Political competition provides incentives for national and local elites vying for power to make use of violence for electoral gains. The risks of a violent escalation are, therefore, higher in Nigeria’s most contested electoral battlegrounds and places where the competition between parties can link up with local conflicts over resources, identities, and power. In the end, the elections in Africa’s most populous state will also constitute a larger test for the health of democracy in the continent.

Visuals in this report were produced by Christian Jaffe