Actor Profile:

The Jalisco New Generation Cartel (CJNG)

14 April 2023

Introduction

The Jalisco New Generation Cartel (CJNG) is a Mexican criminal group that emerged as a splinter group of the Milenio Cartel – one of the Sinaloa Cartel’s allies – after the capture of its leader in 2009 led to internal divisions.1Samuel Henkin, ‘Tracking Cartels Infographic Series: The Violent Rise of Cártel de Jalisco Nuevo Generación (CJNG),’ START, June 2020; El Informador, ‘Cártel de Jalisco, herencia de Ignacio “Nacho” Coronel,’ 8 October 2011; El Informador, ‘Extraditan a líder del cártel de Los Valencia a EU,’ 30 January 2011 Initially, the group operated as an armed wing of the Sinaloa Cartel. As part of this alliance, it engaged in a deadly turf war against Los Zetas in Veracruz state, where the group stood out for its use of violence and involvement in numerous massacres.2Parker Asmann, ‘Masacre en Veracruz remata sangriento inicio de 2019 en México,’ InSight Crime, 24 April 2019

Under the leadership of Nemesio Oseguera Cervantes, also known as El Mencho, the CJNG grew as an independent organization and one of the most powerful actors in Mexico’s criminal underworld. Rivaling its erstwhile ally, the Sinaloa Cartel, the CJNG turned from an armed wing into a complex drug-producing and trafficking structure, which supplies markets across the globe.3Luis Alonso Pérez, ‘La evolución del Cártel Jalisco Nueva Generación: de la extinción al dominio global,’ Animal Político, 2016 It has diversified its activities and sources of income, relying on extortion, kidnapping, human trafficking, illegal mining, and oil theft,4Nathan P. Jones, ‘The Strategic Implications of the Cártel de Jalisco Nueva Generación,’ Journal of Strategic Security, 2018, p.26 such as the capture of the avocado and oil trade in Michoacán and Guanajuato states.5Cat Rainsford, ‘Mexico’s Cartels Fighting it Out for Control of Avocado Business,’ InSight Crime, 30 September 2019; Parker Asmann, ‘Mexico’s Lucrative Oil Theft Industry Fueling Increased Criminal Violence,’ InSight Crime, 4 October 2018 To support its growth and international ambitions, the CJNG has expanded its presence to at least 27 of Mexico’s 32 states.6Carlos Arrieta, ‘Cárteles del narco en méxico; el mapa de en dónde se encuentran,’ El Universal, 22 September 2020 The presence of the CJNG has often driven increased violence at the local level, notably in areas of territorial dispute with other criminal groups.

The CJNG has also relied on alliances to expand its territorial control, including with independent groups that emerged from splintering larger organizations, or groups seeking to offset the expansion of a rival organization.7Alejandro Pocoroba and Laura H. Atuesta, ‘Alianzas y rivalidades de los grupos criminales en México 2020,’ Animal Político, 1 February 2022 For instance, between 2012 and 2013, the CJNG developed ties with self-defense groups in the Tierra Caliente region to support its expansion in Michoacán and Guerrero states. Analysis of the CJNG’s relations with other groups suggests that the CJNG holds ties with at least 37 affiliated criminal groups and that – unlike its rival, the Sinaloa Cartel – it maintains a hierarchical and centralized structure, preventing internal alliances between subordinated criminal organizations.8Nathan P. Jones, Irina A. Chindea, Daniel Weisz Argomedo, John P. Sullivan, ‘A Social Network Analysis of Mexico’s Dark Network Alliance Structure,’ Journal of Strategic Security, 2022, p.76, p.88 To capture the full extent of the CJNG’s activity, this report analyzes violence attributed to the CJNG and its affiliated groups.9For the purpose of this report, CJNG’s affiliated groups are determined based on the network analysis of Nathan P. Jones, Irina A. Chindea, Daniel Weisz Argomedo, John P. Sullivan, ‘A Social Network Analysis of Mexico’s Dark Network Alliance Structure,’ Journal of Strategic Security, 2022, p.7

ACLED tracks violence involving the CJNG and affiliates when they are identified, including when they directly claim responsibility for violence or when ‘narcomessages’ with their signatures are found. In most cases, however, violence remains unassigned,10For more on how ACLED codes criminal violence and unidentified actors, see ACLED Gang Violence: Concepts, Benchmarks and Coding Rules. amid a high impunity rate, lack of investigations, and journalists’ self-censorship stemming from security threats.11Carolina de Assis, ‘Self-censorship and collective action are strategies used by journalists in Mexico and Brazil to deal with risk, study points out,’ The Knight Center for Journalism in the Americas at the University of Texas at Austin, 11 August 2021 The data presented in this report should therefore be understood as indicative rather than representative of the entirety of CJNG activity.12While reports of violence do not always allow the identification of the perpetrators, ACLED data capture areas where the CJNG’s activity has been the most visible and, as well as general levels of violence in areas where investigations determine the CJNG operates.

This report explores how the CJNG has engaged in violence since 2018. It highlights the CJNG’s use of violence against civilians as part of social control measures in its strongholds, and to instill fear among the population against the backdrop of turf wars with other groups in disputed areas. At the same time, the report tracks areas of heightened CJNG engagement in clashes with other armed groups, including areas where the CJNG has sought territorial expansion and areas where broken alliances have disrupted traditional CJNG dominance.

Area of Operations

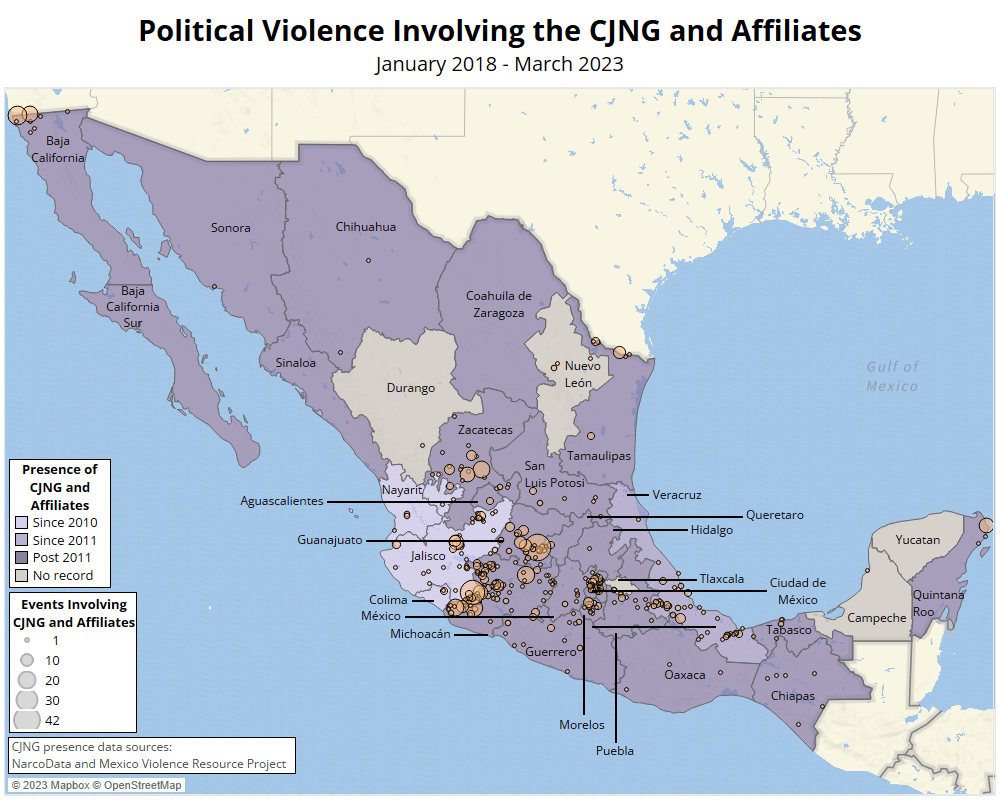

Since its creation, the CJNG has had a foothold in the central-western states of Colima, Jalisco, and Nayarit. The group’s presence was recorded in these states as early as 2010, and in Veracruz state, where the CJNG has operated since 2011.13Mapping Criminal Organizations in Mexico, ‘State Charts. State level criminal groups presence through time,’ visualization by Michael Lettieri, Mexico Violence Resource Project, 2021 Beyond consolidating its presence near areas with already-existing footholds as part of its former Milenio Cartel affiliation, the CJNG also seeks to expand its operations across the country to control strategic drug trafficking corridors, such as routes connecting the Pacific and Atlantic oceans, and the United States border. This has led to high levels of CJNG and affiliates’ activity and violence in other central-western states of the country, such as Guanajuato, Michoacán, and Zacatecas, where the CJNG has had a presence since 2012 (see map below).

Information on the presence of CJNG and affiliated groups per state is sourced from the NarcoData project (2020) and Mexico Violence Resource Project (2021).

Areas with Early CJNG Presence

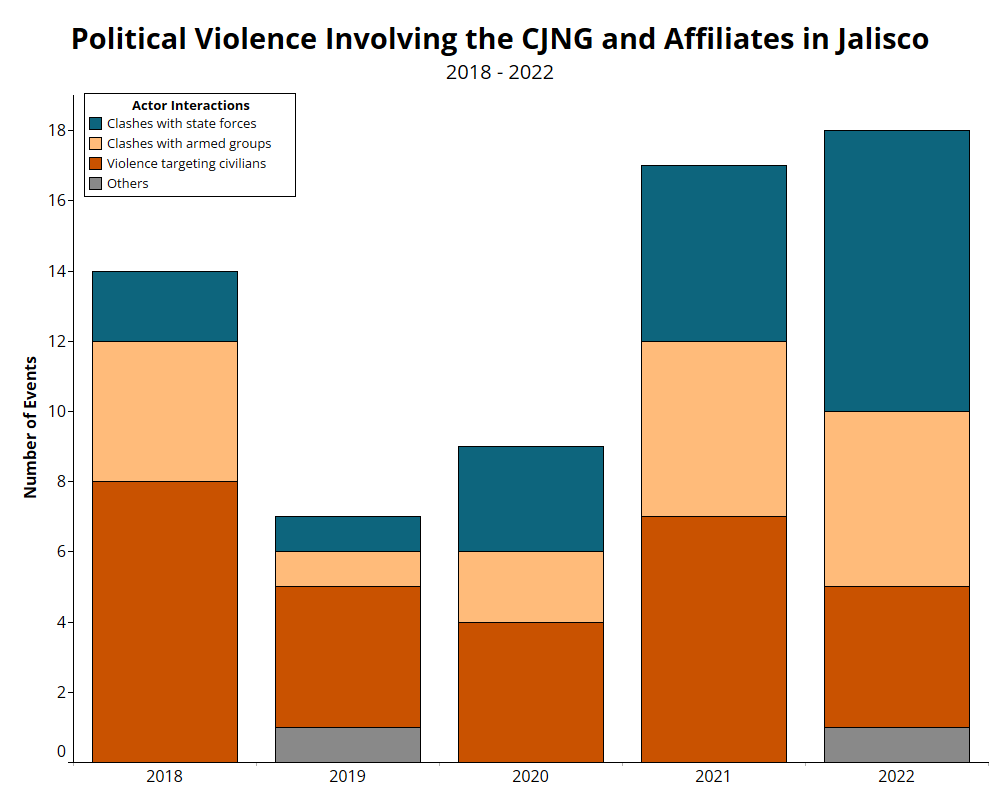

The CJNG has operated in Jalisco since 2010 and has gradually gained dominance in the drug sales and trafficking market.14José Réyez, ‘Radiografía criminal de Cártel Jalisco Nuevo Generación,’ Contralínea, 9 October 2022 In this state, the CJNG and its affiliates have predominantly engaged in violence targeting civilians, which represents over 40% of their activity since 2018 (see graph below). Taken together, the activities of the CJNG and its affiliates have contributed to driving violence in Jalisco, which remains one of the most violent states across Mexico.

Meanwhile, clashes with armed groups only account for a quarter of their activity, likely owed to the CJNG’s increasingly dominant presence in the state.15Expansión Política, ‘Jalisco, ¿paraíso para cárteles? Ésta es su radiografía de violencia y criminal,’ 22 October 2022 These clashes have concentrated in Guadalajara city and surrounding municipalities, where criminal groups fight over local drug markets. Since 2021, however, clashes with armed groups account for a growing share of the CJNG’s activity, notably due to conflicts with the Sinaloa Cartel and Los Pájaros Sierra – formerly allied with the CJNG – in municipalities bordering Zacatecas and Michoacán states.16Síntesis, ‘Mazamitla, ciudad envuelta en disputa del CJNG contra Pájaros Sierra,’ 3 May 2022; Arely Fernández, ‘Cártel de Sinaloa contra CJNG: las raíces de la narcoguerra en Jalisco por la gente de El Chapo,’ 17 November 2022 Similarly, the CJNG and affiliates have increasingly engaged in clashes with security forces since 2021, following a progressively increased deployment of military and National Guard officers to fight insecurity in the Guadalajara metropolitan area and along the state’s borders.17Secretaría de Defensa Nacional, ‘Acciones de Seguridad en Jalisco,’ Gobierno de Mexico, 10 February 2023; Rubí Bobadilla, ‘Guardia Nacional: Llegan 280 militares a Jalisco para reforzar seguridad; suman casi dos mil agentes,’ El Informador, 27 July 2022 In February 2023, federal authorities assumed control of security operations in municipalities along the border with Zacatecas.18El Informador, ‘Por violencia, Sedena controla límites entre Jalisco y Zacatecas.’ 11 February 2023

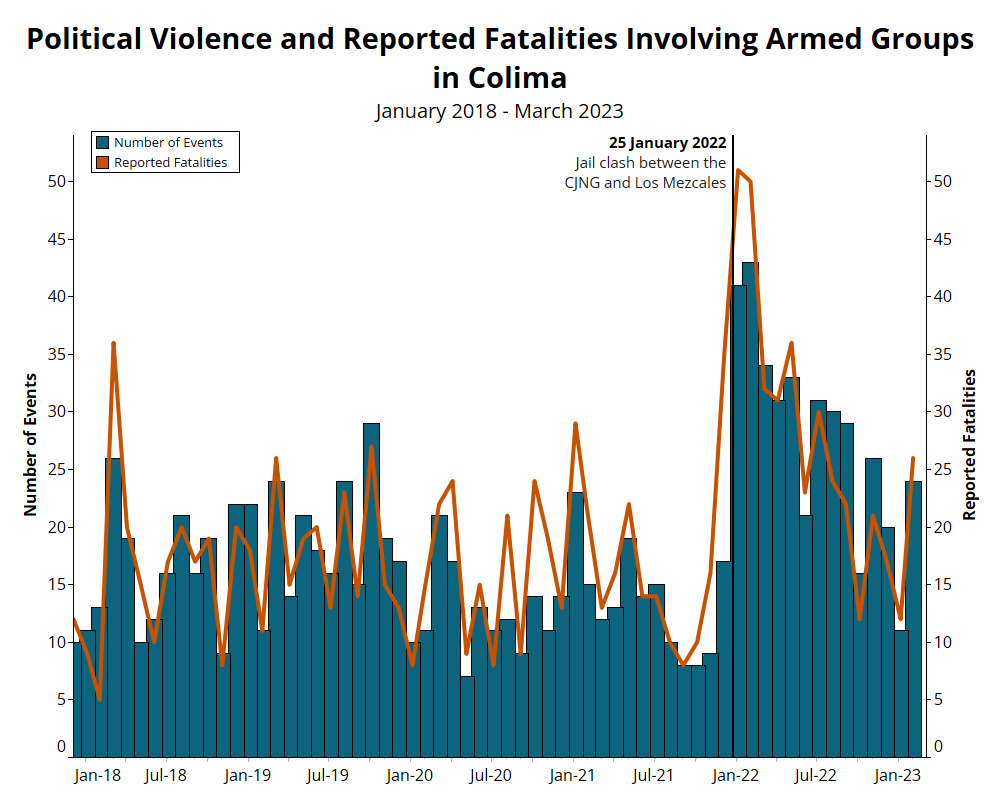

The neighboring Nayarit and Colima states have instead experienced lower levels of violence compared to other states, likely due to the CJNG’s hegemony over criminal activity there.19Infobae, ‘El imperio del narco: al CJNG solo le faltan 4 estados para dominar todo México’, 3 August 2022 Violence in these states, similarly to Jalisco, mainly consists of civilian targeting. In Colima state, when the alliance between the CJNG and the Los Mezcales gang broke off in 2022, violent confrontations erupted. While the CJNG has adopted a centralized structure to prevent sub-alliances and preserve its leadership through tight control over its allies, the dispute with Los Mezcales shows that it remains vulnerable to fragmentation.20Nathan P. Jones, Irina A. Chindea, Daniel Weisz Argomedo, John P. Sullivan, ‘A Social Network Analysis of Mexico’s Dark Network Alliance Structure,’ Journal of Strategic Security, 2022, p.89 The alliance ended following a jail clash between gang members on 25 January 2022 that resulted in nine reported deaths. Since then, the groups have fought for control of Colima and the area around Manzanillo port, a strategic entry point for drug production chemical precursors from Asia.21Ollinka Méndez, ‘Los Mezcales vs CJNG: La ruptura entre cárteles que generó la ola de violencia en Colima,’ El Universal, 19 August 2022 The clashes – allegedly prompted by a new alliance between Los Mezcales and the Sinaloa Cartel22Lidia Arista, ‘La pelea por el puerto de Manzanillo sume a Colima en otra ola de violencia,’ Expansión Política, 9 March 2022 – contributed to the doubling of violence in 2022, compared to levels recorded in the two years prior (see graph below).

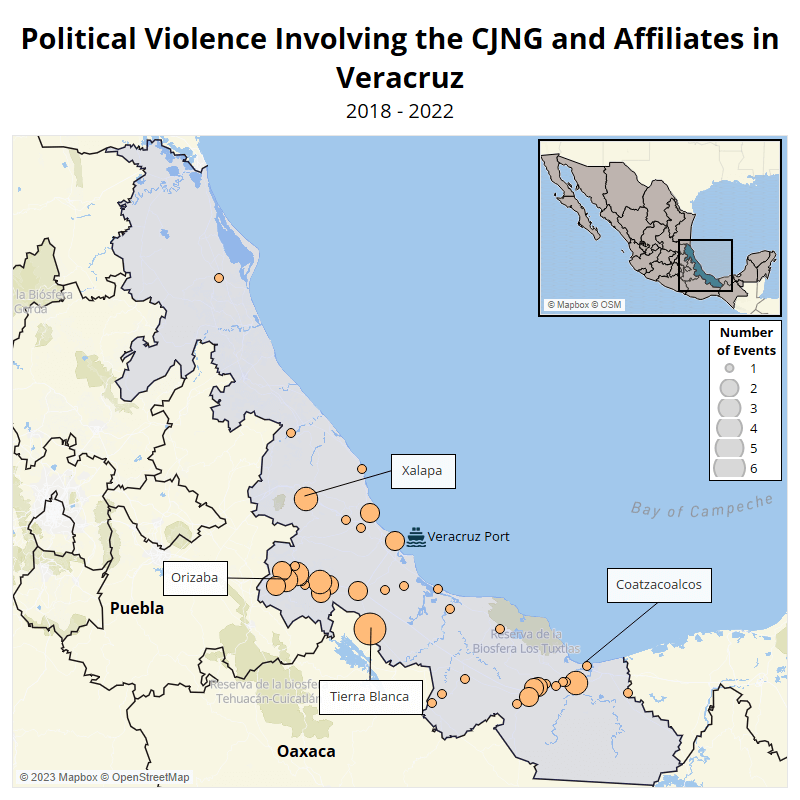

Elsewhere, in Veracruz state, the CJNG consolidated its presence despite an ongoing competition with other groups. After the Los Zetas gang began to fragment in 2012,23Parker Asmann, ‘Mexico’s Zetas: From Criminal Powerhouse to Fragmented Remnants’, InSight Crime, 6 April 2018 the CJNG took control of several areas of this state – including the port of Veracruz, which provides a strategic exit to the Atlantic ocean and drug trafficking corridors to Europe.24La Silla Rota, ‘La guerra que “Los Zetas” y el CJNG llevaron a Veracruz,’ 23 April 2019 However, remnant groups of Los Zetas and groups allied to the Gulf Cartel dispute control across the state,25Infobae, ‘“Esta plaza tiene dueño”: la violenta disputa entre el Grupo Sombra y el CJNG que azota a Veracruz,’ 22 September 2020 leading to sustained high levels of violence involving armed groups in Veracruz. Similar to other states with an early presence of the CJNG and its affiliates, civilian targeting represents a larger share of their activity compared to clashes with armed groups. Since 2019, they have also increasingly engaged in clashes with security forces, following operations against organized crime ramping up.26Mexico News Daily, ‘Jalisco New Generation Cartel goes on the offensive in Veracruz,’ 16 March 2019 Violence by the CJNG in Veracruz state has focused in the south and center of this state, particularly on the Pacific coast between Coatzacoalcos, Veracruz, and Xalapa municipalities, and along the border with Puebla and Oaxaca states (see map below). CJNG activity in areas along the Puebla state border has focused on controlling extortions and routes for oil trafficking,27Infobae, ‘CJNG, Zetas, huachicol y robo: los detalles detrás de la balacera en Orizaba,’ 13 September 2022; Gustavo Castillo, ‘Detienen en Puebla a narco que cobraba cuotas por huachicol,’ La Jornada, 19 December 2021 while the municipalities along the border with Oaxaca have been strategic for human and drug trafficking.28Reforma, ‘Azota crimen límites de Veracruz-Oaxaca,’ 12 January 2022

CJNG Territorial Expansion and Violent Offensive

While the CJNG has maintained control over its traditional areas of operation, it has also sought to expand its control over drug trafficking routes and diversify its revenue streams. Since 2018, the highest levels of activity by the CJNG and its affiliates are recorded in Guanajuato, Michoacán, and Zacatecas states. In Michoacán and Zacatecas specifically, the CJNG presence has likely driven some of the highest levels of inter-armed groups clashes relative to the total political violence events involving armed groups in the state. Meanwhile in Guanajuato, the CJNG has mainly engaged in civilian targeting as part of indirect confrontations with rival groups.

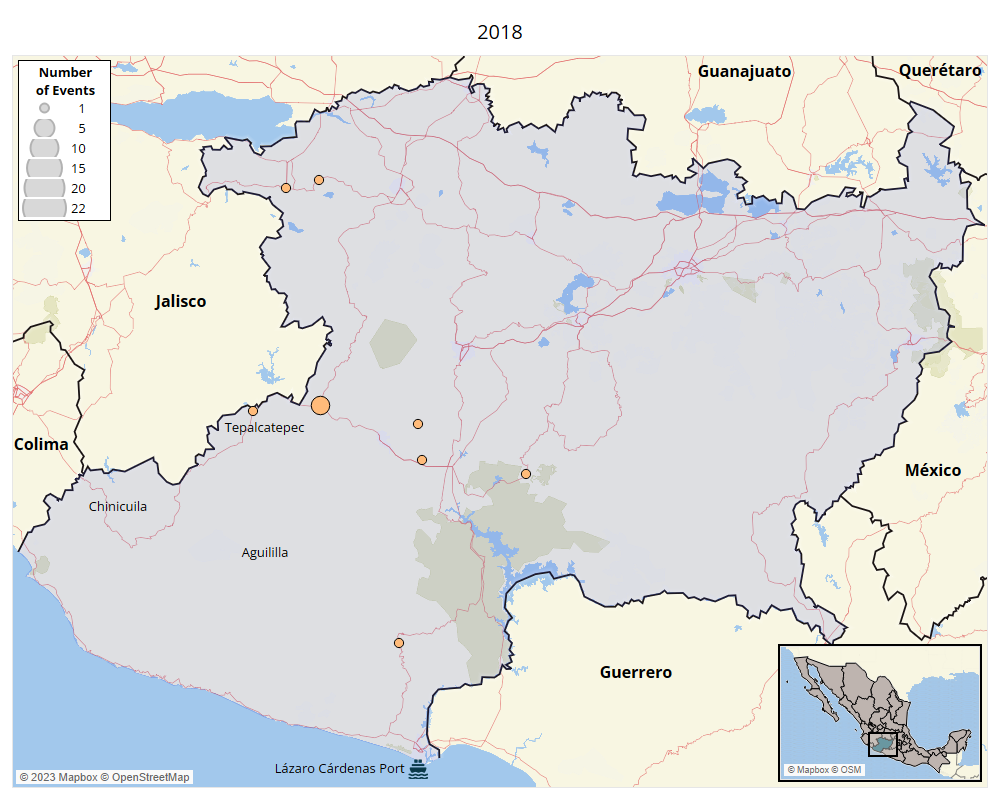

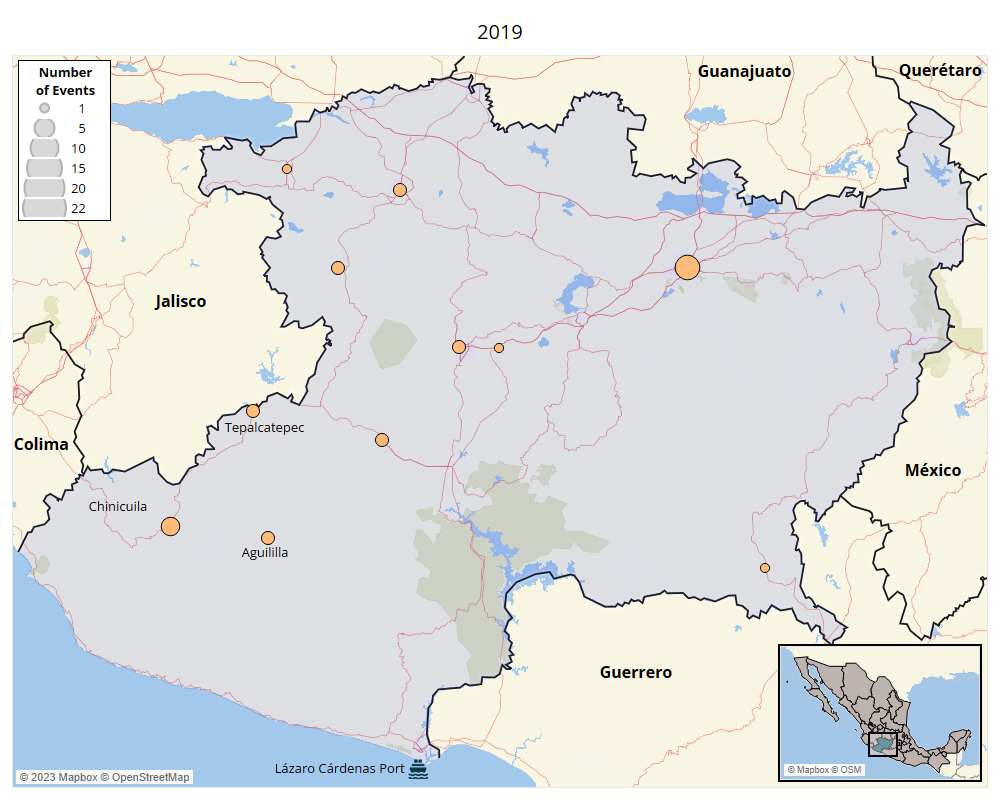

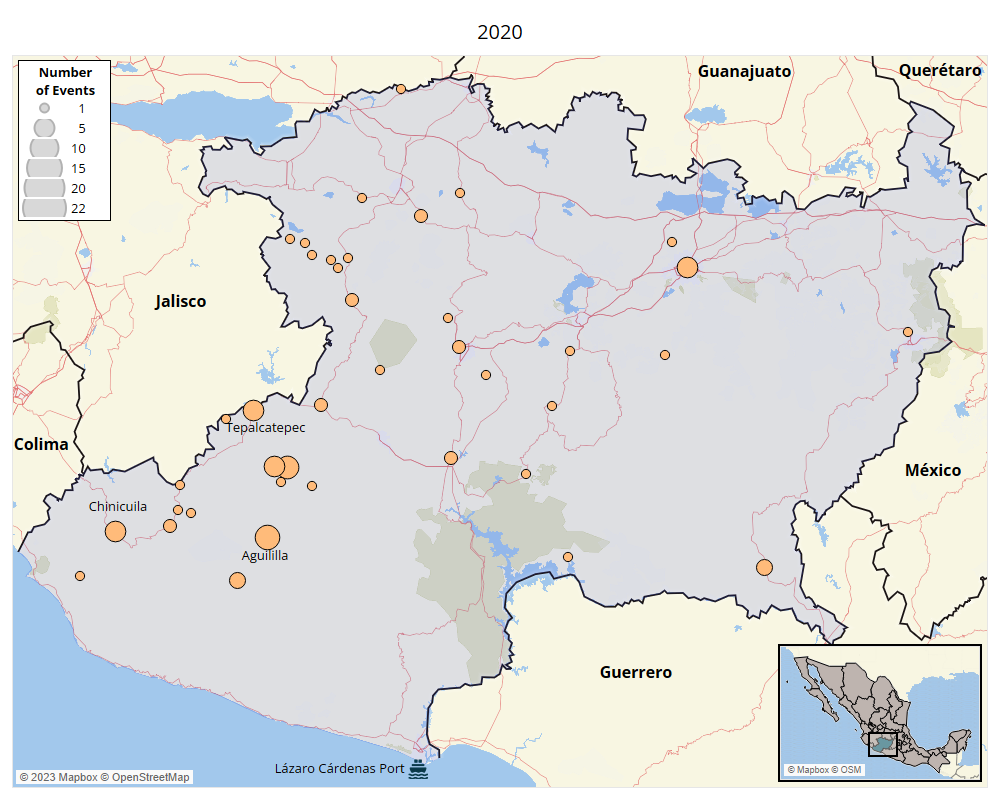

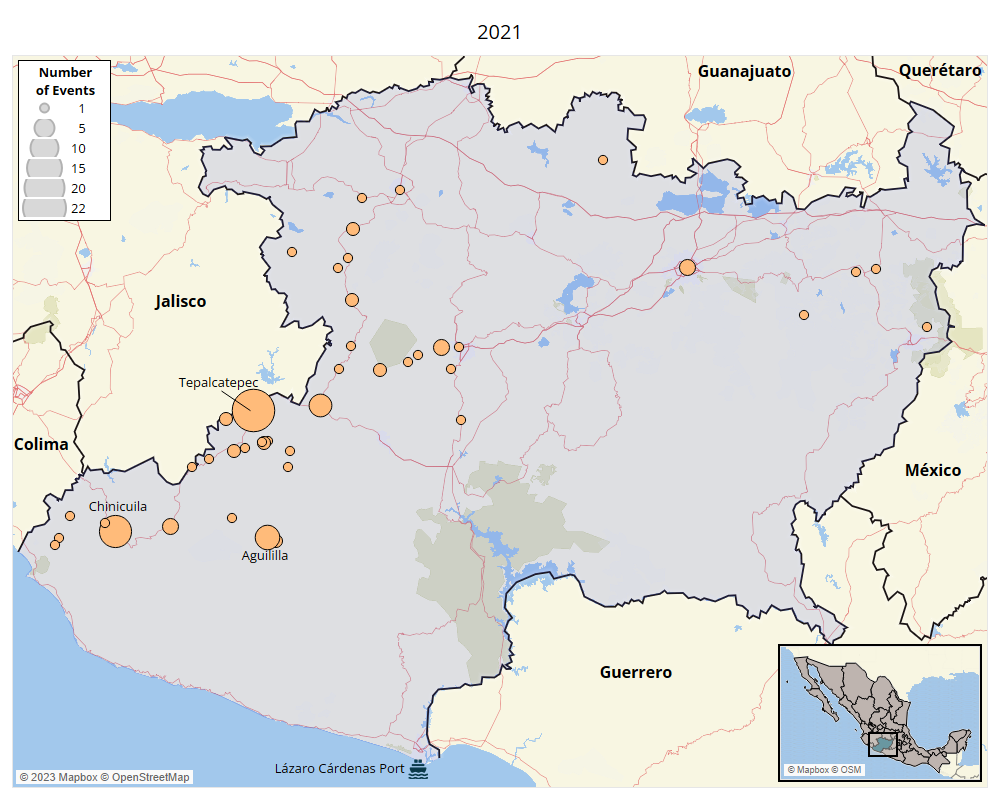

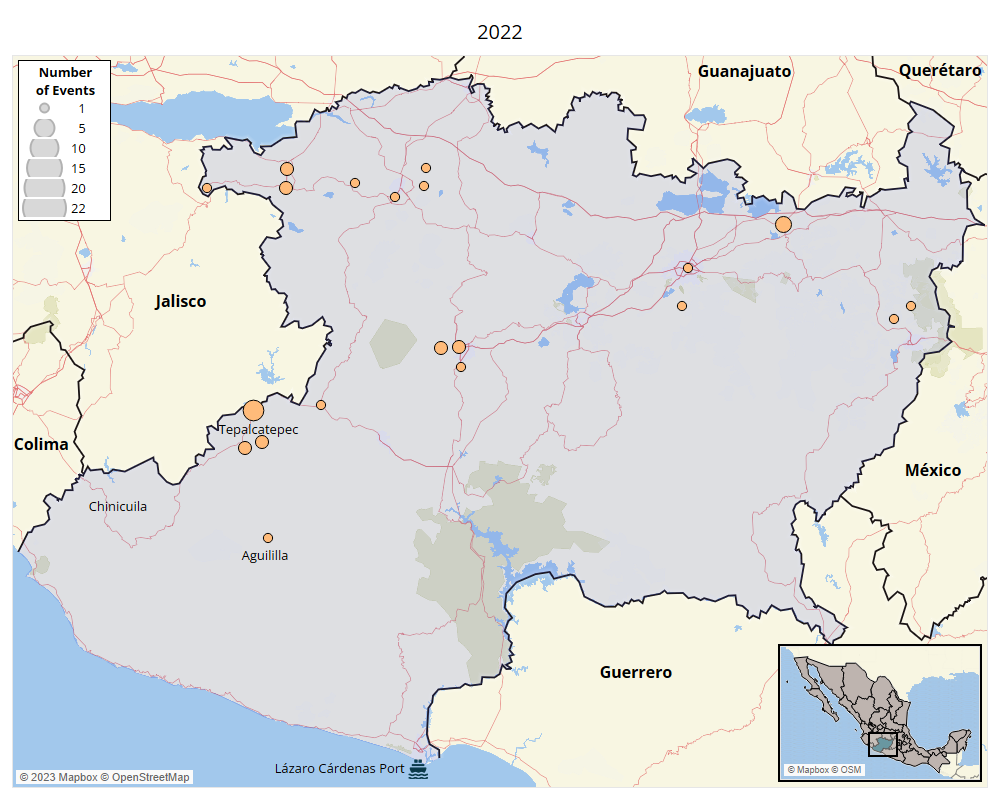

In Michoacán state, the CJNG has increased its offensive in the western municipalities to increase its territorial control in areas bordering its stronghold in Jalisco. In this state, ACLED records the highest numbers of events reportedly attributed to the CJNG. Notably, the CJNG has sought to dominate drug trafficking routes, the extortion of local farmers working in the lucrative avocado production,29Infobae, ‘Las nuevas revelaciones del asedio del CJNG en Michoacán: del tráfico de drogas al control del “oro verde,’ 4 February 2023 and municipalities connecting to the Lázaro Cárdenas port.30Marcos González Díaz, ‘Aguililla, el pueblo de Michoacán asediado por el narco que se convirtió en epicentro de la violencia incontrolable en México,’ BBC, 12 August 2021 Since 2019, political violence involving the CJNG and affiliates in Michoacán has increased and reached a peak in 2021, especially in Tepalcatepec, Aguililla, and Chinicuila municipalities where the CJNG engaged in a turf war against self-defense militias and local criminal groups (see maps below). This increasing violence reflected the breakdown of the alliance between the CJNG and local self-defense leader Juan José Farías, popularly known as ‘El Abuelo’.31Infobae, ‘El “Mencho” vs. el “Abuelo” Farías: la guerra a muerte que desató la violencia en Michoacán,’ 8 January 2021 In Michoacán, local criminal cartels frequently sponsored vigilante groups in exchange for their readiness to be deployed to conflict zones as backup.32Romain Le Cour Grandmaison, ‘Ten Years of Vigilantes. The Mexican Autodefensas,’ Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, March 2023 A loose alliance between local criminal cartels and self-defense groups, including the Los Viagras, La Familia Michoacana, and the Cartel del Abuelo, materialized in 2019 when they formed the Cárteles Unidos (United Cartels) to counter the increasing expansion of the CJNG in Michoacán.33InSight Crime, ‘Carteles Unidos,’ 25 May 2021 Between 2020 and 2021, this competition for local control escalated in a series of heavy clashes between the CJNG and the United Cartels.

Political Violence Involving the CJNG and Affiliates in Michoacán

As the CJNG pursued its operations in the western part of Michoacán, in April 2021, it seized control of Aguililla municipality. Here, the CJNG set up roadblocks to prevent the entry of security forces and rival groups to the municipality, displacing local residents and besieging those who remained in the area.34Marcos González, ‘Aguililla, el pueblo de Michoacán asediado por el narco que se convirtió en epicentro de la violencia incontrolable en México,’ BBC, 12 August 2021; Pablo Ferri, ‘Llegan los criminales y te tienes que salir,’ El País, 22 April 2021 While federal and state security forces eventually reclaimed control over the municipality in February 2022, the CJNG has continued to directly confront the government, killing the mayor of Aguililla in March 2022.35El Economista, ‘Ejército ingresa a Aguililla, Michoacán, y repliega al CJNG y los cárteles unidos,’ 9 February 2022 Although recorded CJNG activity in Michoacán reduced in 2022 compared to levels recorded in 2020 and 2021, overall violence levels in this state have remained high amid continuous warfare with rival groups and internal conflicts. Notably, Los Pajaros Sierra gang – a former armed branch of the CJNG operating at the border between Jalisco and Michoacán – has sought to contest the CJNG’s dominance in the area.36Peter Appleby, ‘Traiciones, disputas internas y un líder misteriosamente desaparecido: ¿se debilita el Cartel de Jalisco?,’ InSight Crime, 25 May 2022

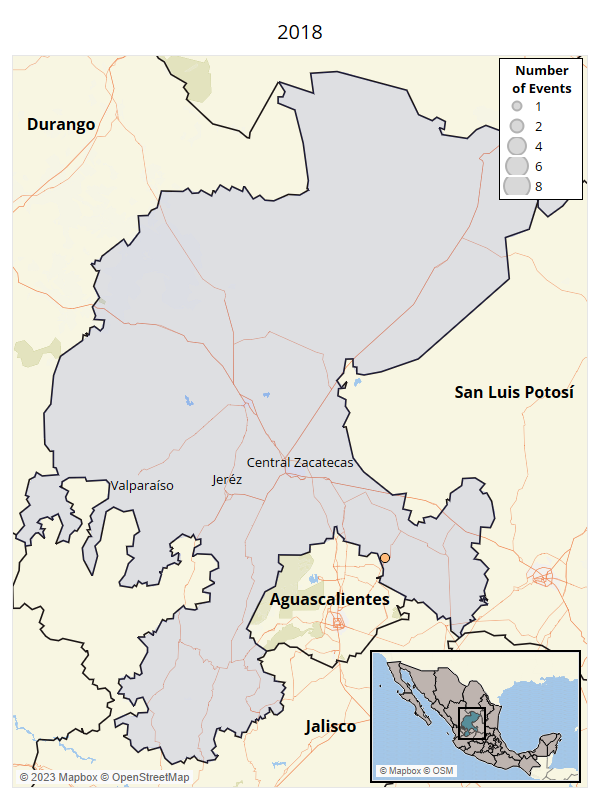

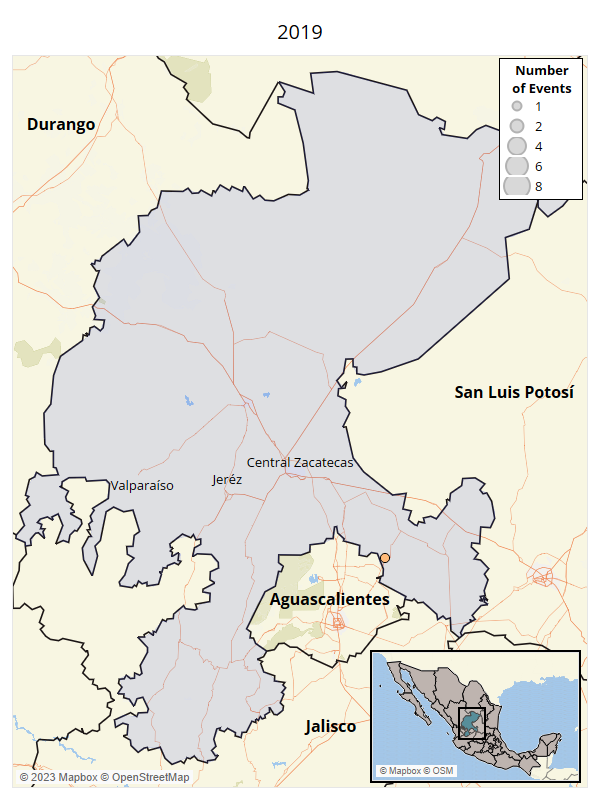

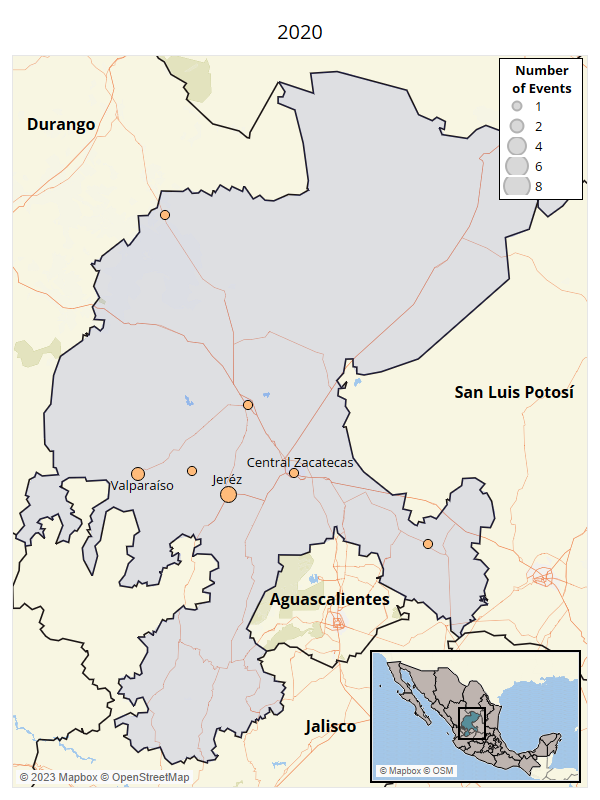

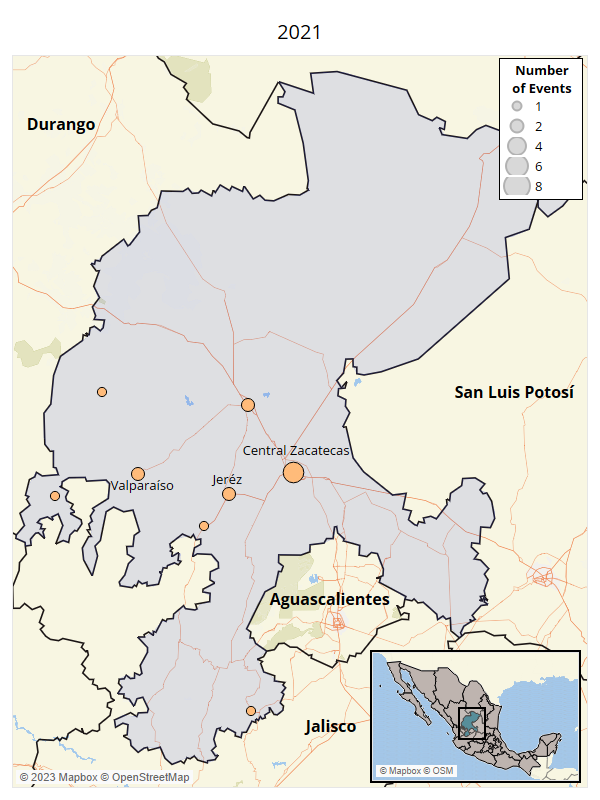

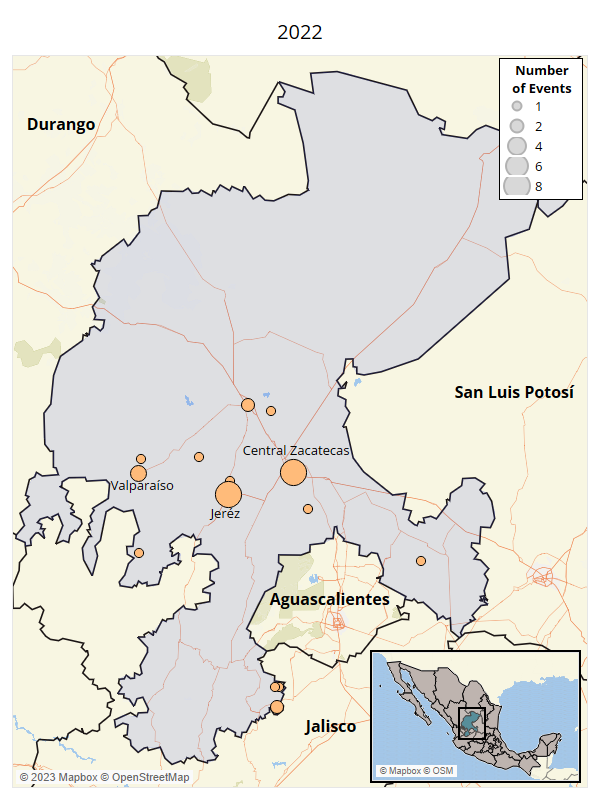

In Zacatecas state, the CJNG has intensified its incursions in the central Zacatecas and Jeréz municipalities, and in southern municipalities along the border with Jalisco, Aguascalientes, and San Luis Potosí states (see maps below). Violence attributed to the CJNG and affiliates began to increase in 2020, contributing to an overall spike in violence. The largest share of this activity is clashes between CJNG and other armed groups over the control of drug trafficking routes and shipping of synthetic drugs.37Thelma Alejandra Mata Hernández, ‘Zacatecas secuestrado por el narco: el caso del corredor industrial,’ Animal Político, 7 June 2022 To address increasing violence, the federal government launched the Support Plan for Zacatecas in November 2021, deploying more than 3,000 military and National Guard officers to Zacatecas and reinforcing security forces presence in neighboring states.38Secretaría de la Defensa Nacional, ‘Ejército Mexicano anuncia Plan de Apoyo a Zacatecas,’ 25 November 2021 Despite these security measures, violence has remained high, reaching a new peak in 2022 when CJNG and affiliates’ involvement in political violence more than doubled compared to 2021, amid intensified clashes between the CJNG and the Sinaloa Cartel. The two cartels have focused their warfare efforts on Zacatecas, Jeréz, and Valparaiso municipalities through which main highways cross to connect the north of the country to the US border.

Political Violence Involving the CJNG and Affiliates in Zacatecas

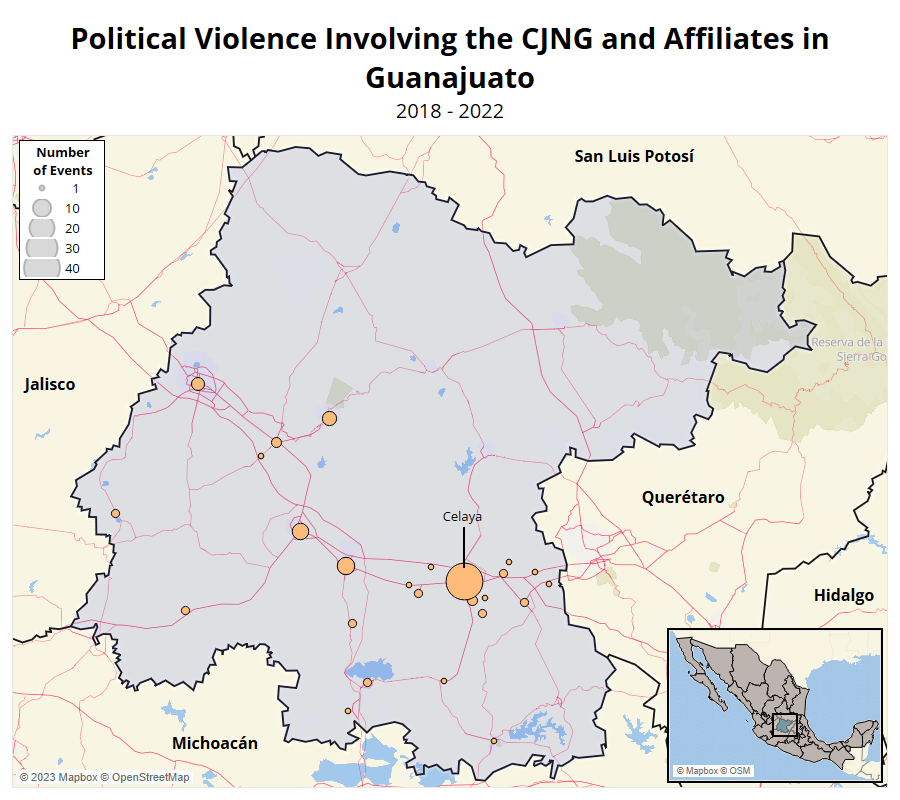

The ongoing conflict between the Santa Rosa de Lima Cartel (SRLC) and the CJNG has contributed to maintaining heightened levels of violence in Guanajuato, where ACLED records the highest levels of political violence involving non-state armed groups in the country.39La Razón, ‘Así es “El Marro” el peligroso líder del cártel Santa Rosa de Lima,’ 3 August 2020 The CJNG’s involvement in violence notably increased in 2020 and concentrated in Celaya municipality, which sits at the intersection of fuel trafficking routes held by the SRLC connecting Querétaro and Hidalgo states (see map below).40Lidia Arista, ‘Drogas sintéticas que hicieron de Celaya la ciudad más peligrosa del mundo,’ Política Expansión, 21 April 2021; Victoria Dittmar, ‘¿Por qué el Cartel de Jalisco no domina México?,’ InSight Crime, 11 June 2020 Through this violence, the CJNG attempted to unseat the SRLC from the control of local drug and smuggling markets and diversify its sources of revenue. Unlike in other states where the CJNG has largely engaged in direct clashes with rivals, in Guanajuato, the CJNG and affiliates more often target civilians than are involved in clashes with armed groups. This finding suggests that the CJNG and rivals have fought for territorial control through localized violence targeting individuals and assets, such as businesses, pipelines and actors involved in oil trafficking, and other sources of revenues. For instance, the CJNG have waged deadly attacks against rival groups suspected of selling drugs in local tire repair shops and bars.41Tomás Andres Michael Carvallo, ‘Why Tire Repair Workshops Are the Target of a Wave of Violence in Guanajuato, Mexico,’ Small Wars Journal, 19 January 2023 Following the arrest of the SRLC leader in August 2020, actions attributable to the CJNG decreased. To date, however, levels remain high compared to other states, as the CJNG continues to dispute territorial control with remnant groups of the SRLC and the Sinaloa Cartel.42Infobae, ‘Aparecieron presuntas narcomantas del Cártel de Sinaloa en 9 municipios de Guanajuato: “Acabar con los ‘marros’,’ 26 September 2022

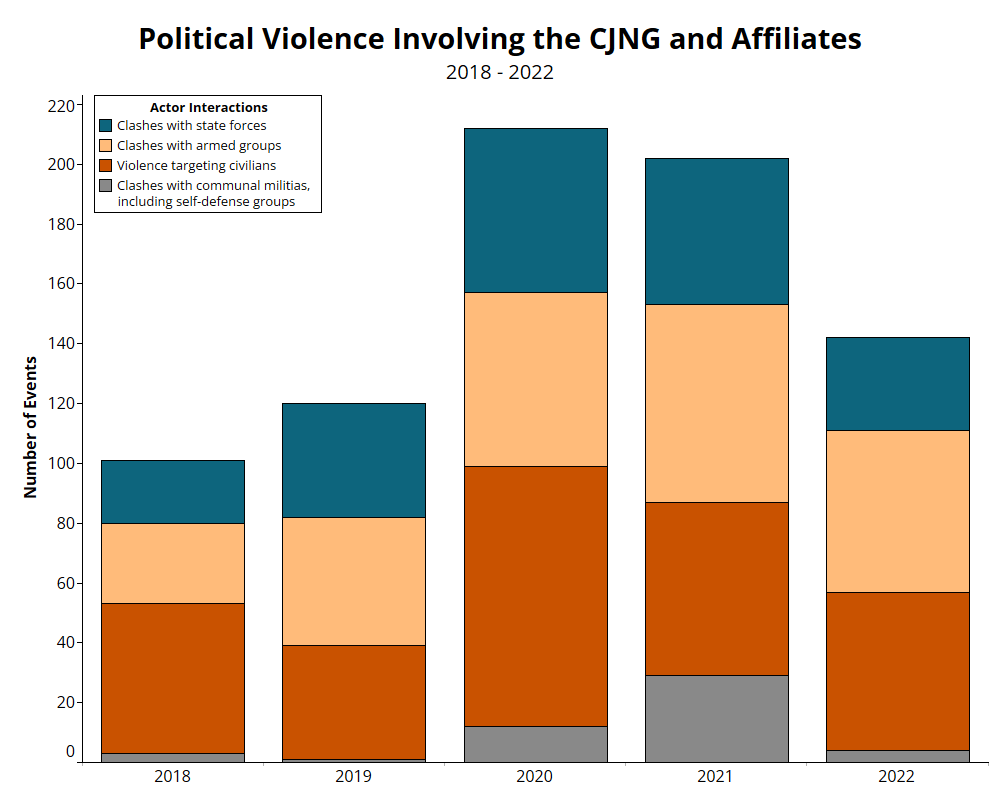

Civilian Targeting as a Territorial Control Strategy

Since 2018, about 47% of violence involving the CJNG and affiliates consists of clashes with other armed groups – representing the largest share of their reported activity (see graph below). Clashes with security forces account for about 17% of the group’s activity. Meanwhile, violence targeting civilians also represents a significant share – about a third – of the CJNG and affiliates’ attributed violence. This, however, is likely an underestimation of CJNG engagement in civilian targeting, as the perpetrators and the motives remain unknown in most cases amid a high impunity rate and lack of resources to investigate.43Human Rights Watch, ‘World Report 2021: Mexico Events of 2020,’ 2021 Since the CJNG emerged, the criminal group has distinguished itself by its extreme and public use of violence – displaying mutilated bodies of its enemies, filmed executions, or using ‘narcomanta’ and ‘narcomessages’ as threats – with the aim of asserting its authority both in territories it controls and areas where it seeks to establish itself.

In the cases where violence targeting civilians is attributable to the CJNG, ACLED records the targeting of specific actors – such as journalists, lawyers, and activists – for interfering with the criminal groups’ activities. In 2022, the CJNG kidnapped two human rights defenders who had opposed mining in the Sierra de Manantlan in Jalisco, and in Guanajuato, the group killed a lawyer who worked for an alleged member of the Santa Rosa de Lima Cartel. The CJNG also reportedly participated in the killing of at least eight current and former government workers and politicians across the country, likely targeted for acting against the interests of the group – including running in local elections or allegedly collaborating with the CJNG’s rivals. Similarly, the CJNG also targets off-duty law enforcement officers, reportedly killing at least five since 2018, in reprisal against law enforcement operations or for their potential collusion with organized crime groups.

Workers and business owners also figure among some of the most targeted actors across the country. While their targeting remains largely underreported and unattributed as many victims face threats and distrust authorities to prosecute the perpetrators, violence has often been linked to extortion schemes involving organized crime groups, but also political and union actors.44Romain Le Cour Grandmaison, ‘La extorsión en México: ¿del silencio a la escalada de violencia? La instalación del cobro de piso por parte del crimen pasa por la construcción y el mantenimiento de un ambiente violento,’ El País, 19 September 2022 Since 2018, ACLED records violence targeting labor groups in municipalities with reported organized crime groups’ activity, with at least eight cases attributed to the CJNG in Guanajuato state. Several attacks have taken place as part of its dispute with the SRLC, with the CJNG claiming responsibility for violence against businesses used as drug selling points or maintaining links with members of the SRLC group.45Aristegui Noticias, ‘Controla CJNG Centros de Rehabilitación en Guanajuato: David Saucedo,’ 2 July 2020 The group has also accused its rival of perpetrating deadly shootings in bars and public spaces to trigger the intervention of security forces in disputed areas and slow down the expansion of the CJNG.46Infobae, ‘Cinco miembros de Pájaros Sierra fueron abatidos por el Ejército en Michoacán,’ 17 November 2022

The CJNG has also increasingly relied on a modern arsenal. Since 2021, ACLED records at least 23 drone strikes with the CJNG carrying out more than half of all drone strikes taking place in Mexico, mainly in Tepalcatepec, Michoacán state. While drones have largely been used for surveillance purposes, in Tepalcatepec, the CJNG has used drones to drop C4 explosives on civilian residences.47Alejandro Santos, ‘Los drones del narco: vigilancia, moda y símbolo estatus,’ 30 January 2022 These attacks have not resulted in any reported fatalities but residents have seen them as a tactic to intimidate and displace them to gain control over the area.48Scott Mistler-Ferguson, ‘Tepalcatepec, Mexico: A Staging Ground for Drone Warfare,’ InSight Crime, 14 January 2022; Infobae, ‘Pobladores de Tepalcatepec atribuyeron al CJNG por ataques con drones armados,’ 11 January 2022 While the use of these weapons is indicative of the group’s relatively advanced resources, they should not be equated to combat drones. Their striking power remains limited, and seems aimed at displaying the CJNG’s status.49Alejandro Santos Cid, ‘Drones: The latest weapon (and status symbol) of Mexico’s cartels,’ El País, 1 February 2022

Looking Forward

With a presence in at least 27 of the 32 Mexican states and a significant role in international drug trafficking, the CJNG is considered one of Mexico’s most powerful criminal groups. In the last five years, the CJNG has extensively engaged in clashes with armed groups, especially in Michoacán and Zacatecas states, where it has sought to expand its control over strategic trafficking routes and resources. It has also relied on civilian targeting as a proxy turf war in Guanajuato, targeting civilian assets affiliated with rival groups. In states where the CJNG has established an early presence, such as Jalisco, Colima, and Veracruz, the group has resorted to using violence against civilians to enhance its social control over the population and deter rivals. The breakdown of alliances have, however, led to violent confrontations with other armed groups seeking to extend their activities into CJNG strongholds.

As the CJNG seeks to assert its dominance, violence is likely to continue at sustained levels in areas under its control and under contestation, with deadly consequences for civilians. Notably, the CJNG’s territorial expansion has faced fierce resistance from rival criminal groups, which have succeeded in building alliances to push back the CJNG’s incursions, as seen with self-defense groups’ participation in clashes along with criminal groups in Michoacán state. As previously observed, significant increases in violence in disputed areas could also translate into additional state interventions and violent clashes with the CJNG, with potential repercussions on civilians.

Additionally, competition for global markets has led to an intensified proxy war in the Americas between local criminal groups involved in drug production and trafficking processes for the CJNG and the Sinaloa Cartel.50Vanda Felbab-Brown, ‘The foreign policies of the Sinaloa Cartel and CJNG – Part I: In the Americas,’ The Brookings Institution, 22 July 2022 Deepening rivalries and the CJNG’s international ambitions could destabilize and lead to increasing criminality in the Americas, but also elsewhere as the criminal group penetrates drugs markets in Africa and Europe.51Vanda Felbab-Brown, ‘The foreign policies of the Sinaloa Cartel and CJNG – Part III: Africa,’ The Brookings Institution, 21 August 2022; Vanda Felbab-Brown, ‘The foreign policies of the Sinaloa Cartel and CJNG – Part IV: Europe’s cocaine and meth markets,’ The Brookings Institution, 2 September 2022 Although the CJNG has developed a hierarchical structure to avoid connections and potential alliances between its subordinates, it remains vulnerable to internal ruptures, as observed in Colima with the breakaway of Los Mezcales to form an alliance with the Sinaloa Cartel, and in Jalisco with los Pájaros Sierra. Its personalized leadership and centralized structure further exposes the criminal group to fragmentation, should its top leadership be dismantled – which could result in additional violence and expose civilians.

Visuals in this report were produced by Ana Marco