Fact Sheet: Conflict Surges in Sudan

Published: 28 April 2023

Last Updated: 24 May 2023

Key Trends

(15 April-19 May 2023)

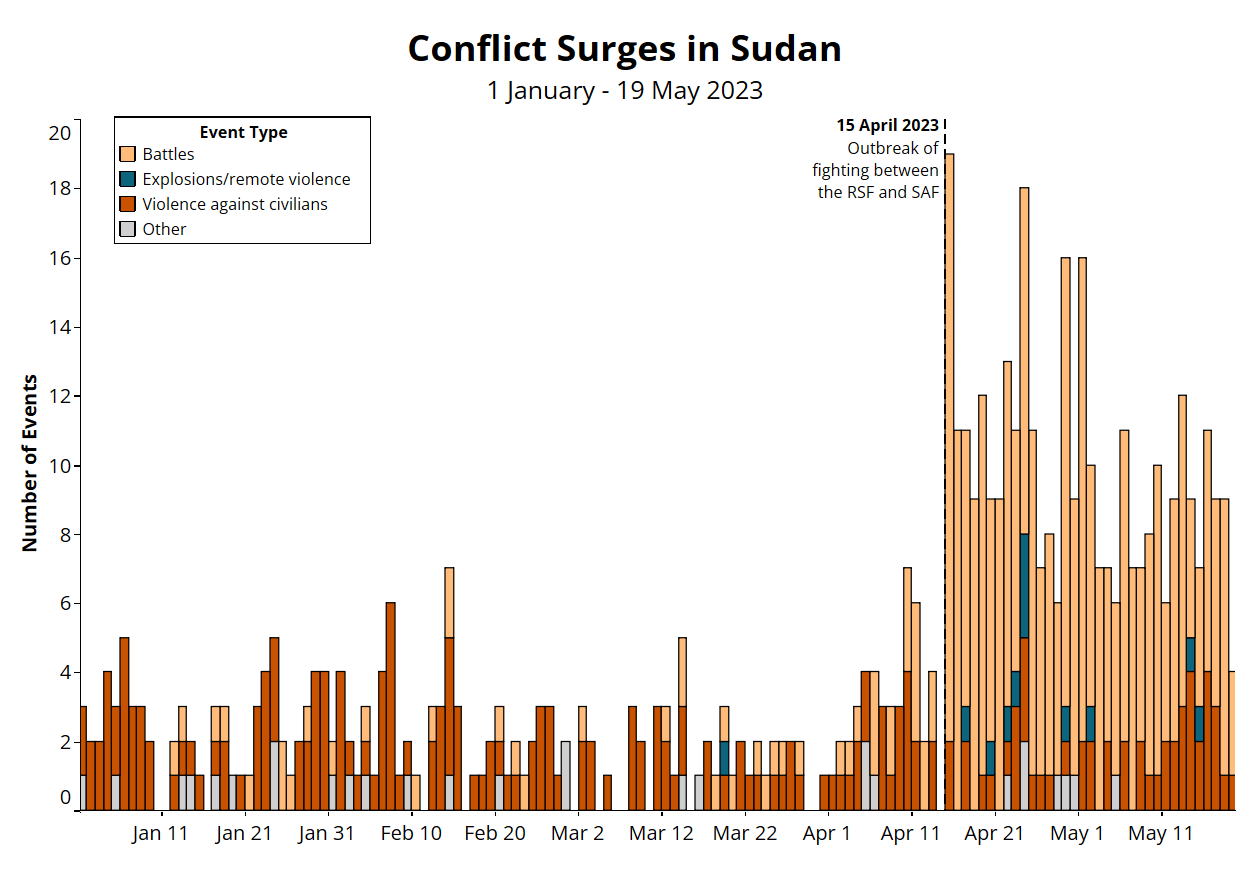

- Since fighting broke out between the Sudanese Armed Forces and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces on 15 April, ACLED has recorded over 340 incidents of political violence around the country, including 275 battle events

- From 15 April to 19 May, clashes increased nearly eightfold compared to the same time period prior

- More than 1,800 fatalities have been reported since the start of the fighting

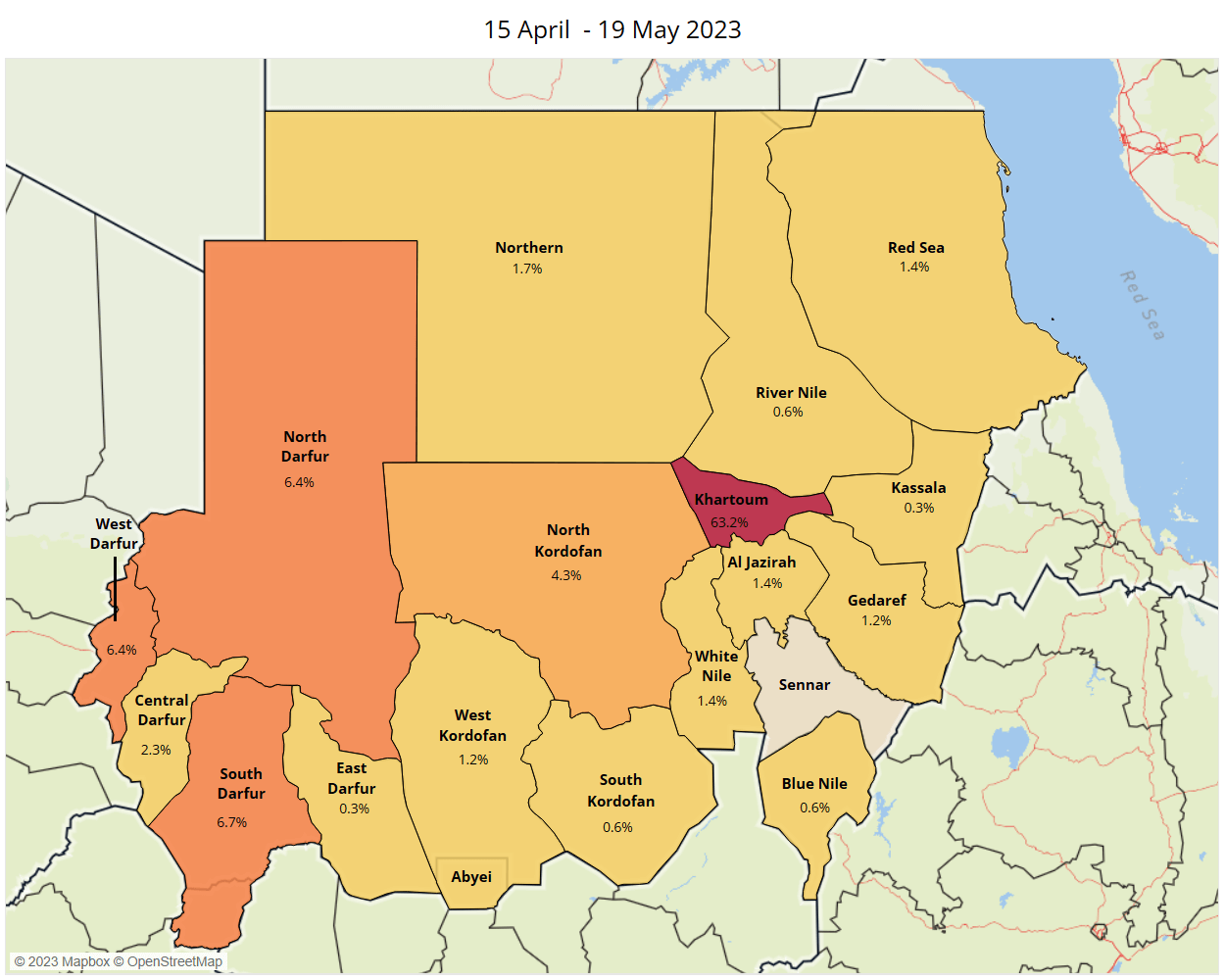

- Conflict has been concentrated in Khartoum state, which has accounted for over 60% of all recorded political violence incidents during this period

- ACLED records nearly 60 civilian targeting incidents since the beginning of the conflict, with over 75% occurring in Khartoum

- The use of explosions/remote violence – such as airstrikes – has reached its highest monthly point in the past six years, with most strikes conducted by the Sudanese Armed Forces in Khartoum

- Over two-thirds of the fighting between the Sudanese Armed Forces and Rapid Support Forces has taken place in cities of over 100,000 people

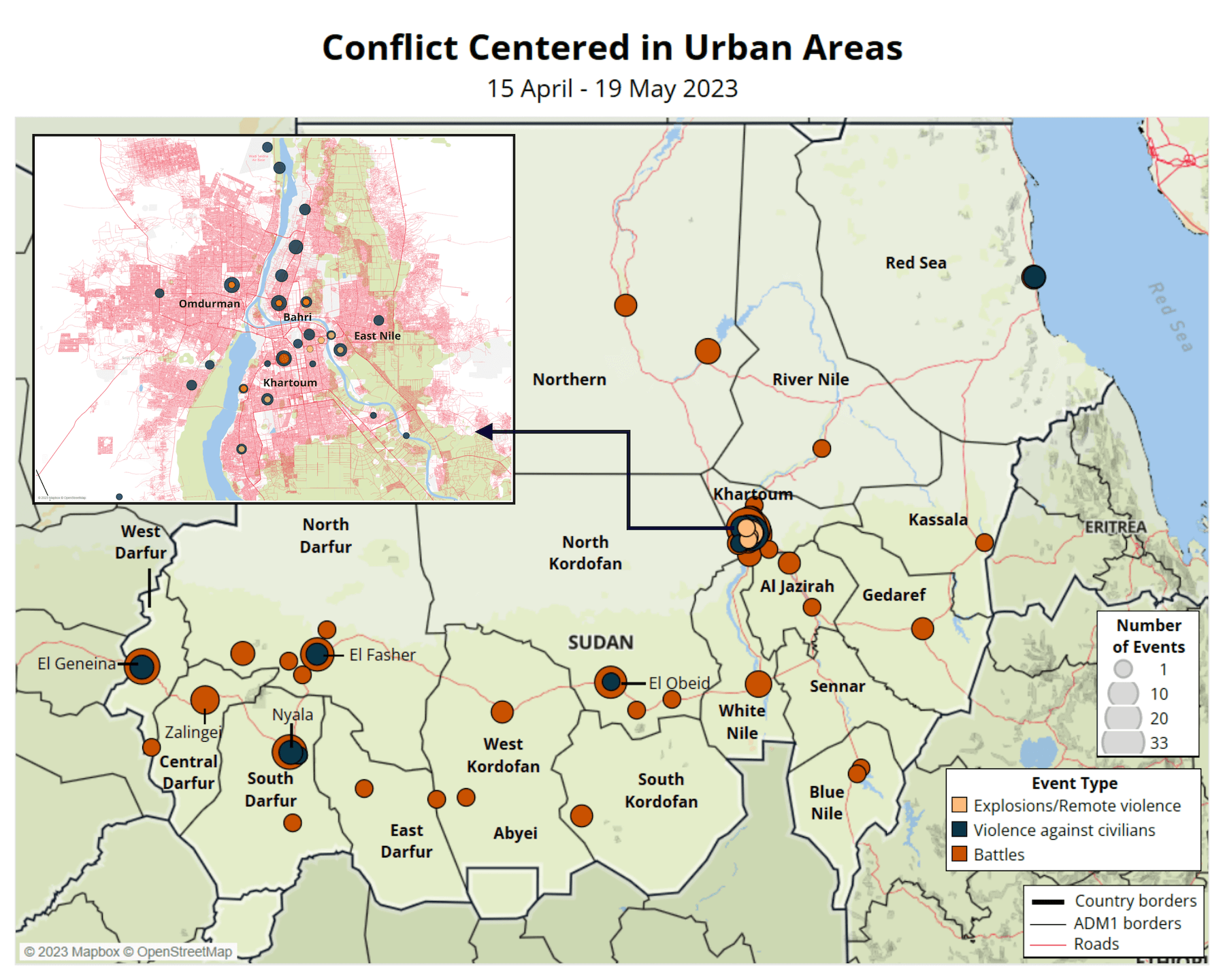

- Battles outside Khartoum have centered in urban areas along major roadways, especially east-west corridors from Kassala to West Darfur

- In West Darfur, fighting between the two sides triggered deadly intercommunal clashes in El Geneina, with a more than fourfold increase in violence in the city compared with the monthly average over the preceding year

- Over 700 fatalities have been reported in El Geneina since 15 April

Overview

On 15 April, fighting erupted in Sudan between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF), aligned with General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), led by Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, popularly known as Hemedti. The clashes represented a definitive breakdown in the delicate power arrangement that had developed between al-Burhan and Hemedti since the removal of Sudan’s former leader, Omar al-Bashir, in April 20191The Economist, ‘A general, a warlord and an economist vie to run Sudan,’ 15 July 2021; Sudan Tribune, ‘Sudan’s hidden power struggle between Burhan, Hemedti over civil service,’ 28 September 2022, and began less than five months after a new framework agreement to relaunch the political process for the country’s transition to a civilian government. The SAF and RSF had shown little willingness to adhere to the framework, failing to agree on plans to integrate the RSF into the military, in what was ultimately a final blow to the transition process.

Increased military exercises and rising tensions between SAF and RSF soldiers foreshadowed fighting in Khartoum in the weeks leading up to the confrontation.2Declan Walsh, ‘2 Generals Took Over a Country. Will They Deliver Democracy or War?’ The New York Times, 6 April 2023 New security measures were also put in place before the onset of the conflict, including increased civilian inspections and frequent closures of roadways and bridges.3Mohammed Amin, Sudan simmers as Burhan-Hemeti rivalry threatens to boil over,’ Middle East Eye, 30 March 2023 Both al-Burhan and Hemedti made rival diplomatic missions to neighboring countries in recent months to solicit support – a clear indicator of the growing rifts despite the public facade of unity.4Declan Walsh, ‘2 Generals Took Over a Country. Will They Deliver Democracy or War?’ New York Times, 6 April 2023; Mohammed Amin, Sudan simmers as Burhan-Hemeti rivalry threatens to boil over,’ Middle East Eye, 30 March 2023; Some also predicted a popular uprising following renewed demonstrations, a crippled economy, and rising violence in Darfur in early April, see The Economist, ‘Sudan faces collapse three years after the fall of its dictator,’ 9 April 2023 This facade violently collapsed under the weight of these tensions on 15 April: during the following weeks, political violence in Sudan reached levels four times higher than in the preceding weeks. Although multiple ceasefires failed to take hold in the first month of the fighting, a recently announced ceasefire seems to have brought relative calm to the capital.5BBC, ‘Sudan ceasefire: Khartoum largely quiet, residents say,’ 23 May 2023 However, pending a shift in the current balance of power, conflict is likely to resume.6Rayhan Uddin, Sudan: Why are ceasefires constantly being broken?, Middle East Eye, 3 May 2023; Katharine Houreld and Hafiz Haroun, ‘Sudan’s warring generals closely matched ahead of latest cease-fire,’ The Washington Post, 3 May 2023

Civilians Caught in the Crossfire of Escalating Fighting Between the SAF and RSF

Clashes between the SAF and RSF have constituted over 70% of all political violence events recorded in Sudan since 15 April. Although attacks using explosives and remote violence have been uncommon in Sudan, making up only 2% of political violence over the past 12 months, the most recent fighting has included frequent airstrikes and shelling incidents targeting military and civilian infrastructure, including hospitals. For example, SAF airstrikes have hit RSF bases in several areas, including the Kafouri area of Bahri, Omdurman, and multiple other areas in Khartoum.

Many civilians have been caught in the crossfire of the conflict and have also been directly targeted outside of the clashes by both sides, with cases including incidents of sexual and gender-based violence.7United Nations Women, ‘Statement on Sudan by UN Women Executive Director Sima Bahous,’ 21 April 2023 While figures from early reports vary as the situation continues to develop, estimates from the Sudan Doctors’ Syndicate put civilian fatalities at over 800.8Eastern Herald, ‘Sudan Doctors Syndicate Announces Latest Civilian Death Toll,’ 17 May 2023 At least 58 civilian targeting events took place during the reporting period, with over 75% occurring in Khartoum. For example, a SAF airstrike hit a residential area south of Khartoum on 24 April, killing several and injuring dozens while destroying houses.

In multiple civilian targeting incidents, RSF and SAF forces have detained and attacked civil society actors and journalists, including an RSF arrest, interrogation, and physical assault of a spokesperson for the Sudanese Democratic Alliance for Social Justice in Khartoum. At the start of the fighting, a SAF soldier detained and assaulted a BBC journalist in Omdurman. ACLED also records at least nine incidents of violence targeting foreign diplomatic personnel and convoys in Omdurman, Khartoum, and en route to Port Sudan. In addition to these attacks, looting and destruction of civilian property are widespread, especially in Khartoum and throughout Darfur, as armed groups exploit the outbreak of conflict to steal from banks, shops, humanitarian offices, hospitals, and homes. The looting of aid has further exacerbated the humanitarian situation in the country.9Malak Harb and Noha Elhennawy, ‘UN humanitarian chief in Sudan, seeking guarantees on aid,’ 3 May 2023 As a result, thousands of people have fled the conflict zones to other areas of Sudan and neighboring countries, while thousands remain trapped amid fighting.10International Organization for Migration, ‘DTM Sudan – Sudan Situation Report,’ 28 April 2023; Ravina Shamdasani, ‘Sudan: Plight of civilians amid hostilities,’ Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, 28 April 2023

On 29 April, the SAF deployed the Central Reserve Police, locally known as Abu Tira, in Khartoum to purportedly “maintain security.”11Sudan Tribune, ‘Sudanese police deploy Central Reserve unites in Khartoum,’ 29 April 2023 Abu Tira forces have been accused of serious human rights violations due to their use of violence against protesters during anti-coup demonstrations in Sudan.12Voice of America, ‘US Sanctions Sudan’s Central Reserve Police Over Human Rights Violations,’ 21 March 2022 ACLED records over 100 civilian targeting events involving the group since 2019, resulting in more than 50 civilian fatalities.

Shifting Geography of Political Violence

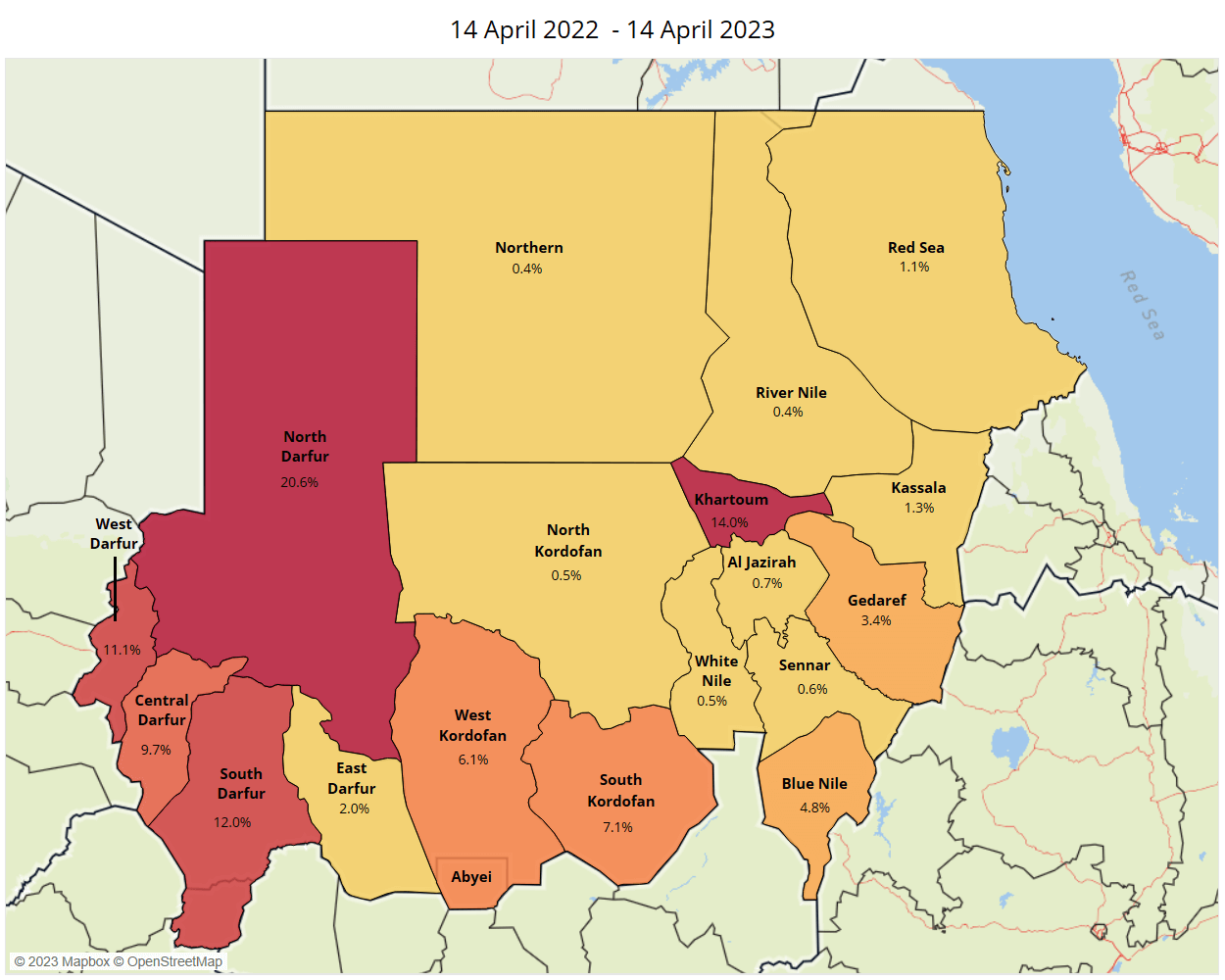

With the escalation of fighting in the capital, the epicenter of political violence has shifted to Khartoum (see maps below). Over the year prior to the latest clashes, Darfur region was the most violent area of the country and home to 56% of all political violence incidents recorded in Sudan. However, during the period of 15 April-19 May 2023, political violence reported in Khartoum grew from the weekly average of 14% of all incidents to over 60%. Violence also escalated in other areas like North Kordofan state and Northern state, which typically experience lower levels of political violence. As the conflict has progressed, fighting between the two sides has become more concentrated geographically. While battle events between the SAF and RSF were reported in 17 states during the first two weeks of fighting, that number decreased to nine during the following weeks.

Most clashes were concentrated in Khartoum and urban areas along major roadways (see map above). Over two-thirds of the fighting between the SAF and RSF has taken place in cities of over 100,000 people.13World Population Review, ‘Population of Cities in Sudan 2023,’ 2023 Outside of battles in Khartoum and neighboring Omdurman and Bahri, fighting was highest in the cities of Nyala, El Geneina, El Obeid, and El Fasher. Fighting between the RSF and SAF outside of Khartoum underscores the RSF’s persistent involvement in Sudan’s peripheral areas. ACLED also records over a dozen territory transfer incidents during the reporting period, with the RSF taking control of areas in at least four locations, including a short overtake of Merowe Airport, and in Nyala, Khartoum, and Khartoum North. In turn, the SAF took control of several RSF headquarters and camps in Port Sudan, Kadugli, and El Fasher. Control of many strategic locations and resources is currently split between the two groups.14Katharine Houreld and Hafiz Haroun, ‘Sudan’s warring generals closely matched ahead of latest cease-fire,’ The Washington Post, 3 May 2023

In some regions, such as Darfur, the SAF and RSF have allegedly engaged in widespread recruitment from local tribal groups in recent months,15Ayin Network, ‘Darfur’s recruitment race: Sudan’s army and Rapid Support Forces compete for influence,’ 26 March 2023 amid reports that the SAF has been targeting forces loyal to Hemedti’s tribal rival Musa Hilal – a claim the SAF refutes.16Sudan Tribune, ‘Sudanese army did not recruit Musa Hilal’s fighters: spokesman,’ 8 March 2023 While many local armed groups outside the country’s main urban areas have not been reported as active in the fighting, these fighters may be operating within the ranks of the SAF or RSF. If the conflict escalates, heightened RSF and SAF engagement outside Khartoum may also exacerbate fighting between local armed groups around the country.

In West Darfur, violence increased by over four times in El Geneina during the past month compared with the monthly average for the preceding year, as clashes between the SAF and RSF triggered deadly intercommunal clashes between Masalit militias and Arab militias affiliated with the RSF.17The Economist, ‘Sudan’s war is home-grown, but risks drawing in outsiders,’ 3 May 2023 In El Fasher, an Arab militia attacked Shala prison in the city, releasing prisoners. Five armed groups that are signatories to the Juba Peace Agreement – Sudan Liberation Movement (SLM) led by Minni Minnawi, SLM-Transitional Council, Justice and Equality Movement, Gathering of Sudan Liberation Forces, and Sudanese Alliance Movement – deployed forces in the city to maintain security. On 8 May, Minnawi withdrew his forces stationed in northern Omdurman to North Darfur.18Sudan Tribune, ‘Minnawi withdraws troops from Khartoum to North Darfur,’ 8 May 2023 These developments have raised fears of a renewed civil war in Darfur.

Distribution of Political Violence Events in Sudan

This fact sheet was updated on 24 May 2023. Click here to download the original version, and click here to download the first update from 5 May 2023. For more Sudan analysis, see our Sudan country hub.

Visuals in this fact sheet were produced by Ana Marco.