Special Issue: Violence Targeting Local Officials

Brazil

Published: 22 June 2023

Organized Crime Exploits Long-Standing Local Feuds

On 14 March 2018, gunmen shot and killed Rio de Janeiro City Councilwoman Marielle Franco. As a queer Black woman deeply involved in the country’s political scene, Franco represented a new generation of empowered favela leaders. She worked to promote the rights of Black women, marginalized communities, and the LGBTQ+ community. While the exact motivations behind her killing remain unclear, her death has been linked to her efforts to limit the expansion of militia groups in her local area.1José Roberto de Toledo, ‘Marielle Franco foi morta por atrapalhar os planos de expansão da milícia,’ UOL, 14 March 2023 Her killing provoked a further polarization of public discourse on race, gender, and social class in the nation, but also brought into the public consciousness the risks faced by local-level elected officials in Brazil.

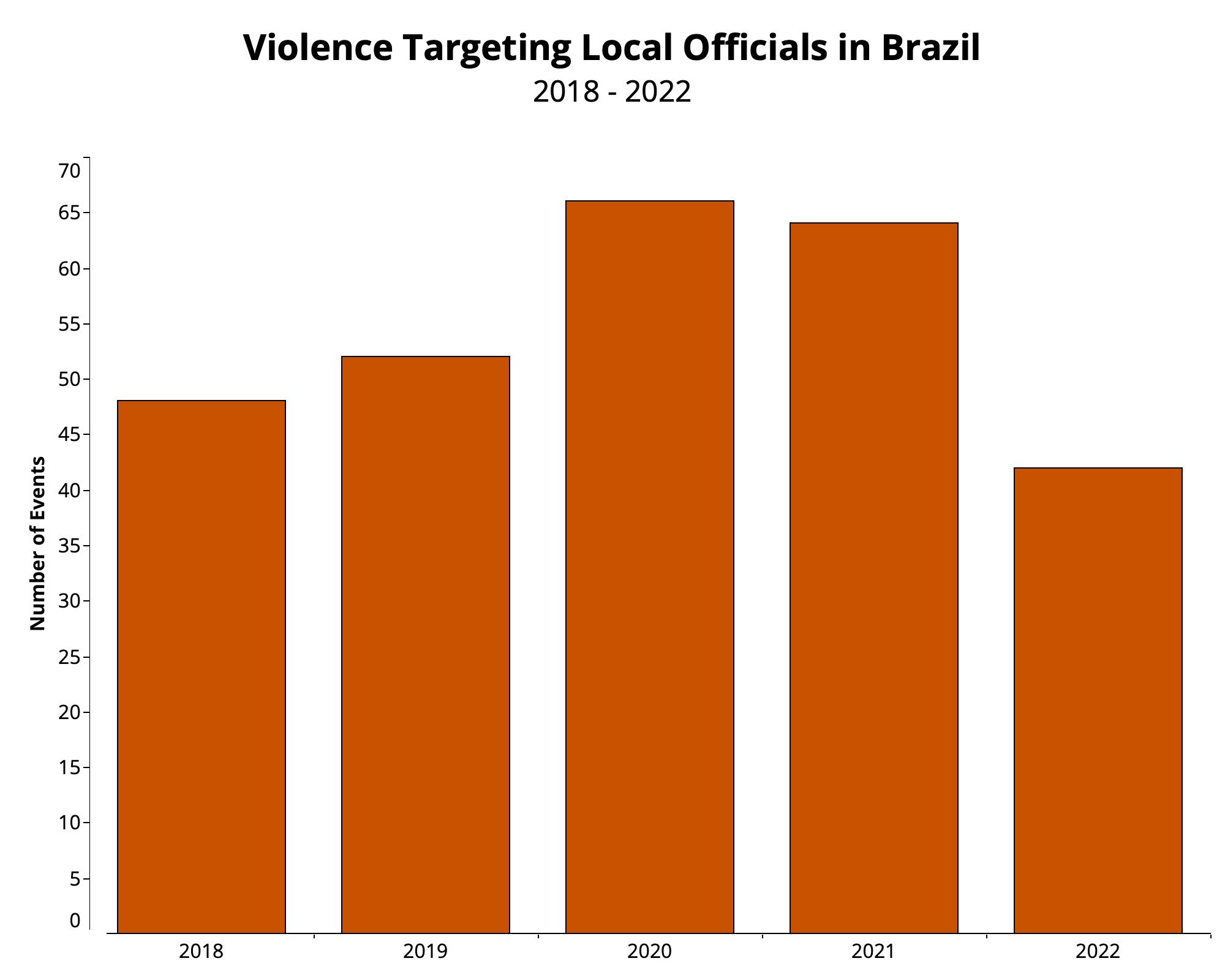

While this killing gained significant attention, it was by no means isolated. Violence has affected officials from all levels and branches of the Brazilian government. Violence targeting high-level officials is still rare, like the assassination attempt on then-candidate Jair Bolsonaro during a political rally in 2018. However, threats and violence towards local officials are a widespread and deadly phenomenon. Between 2018 and 2022, ACLED records 273 events involving local officials in Brazil, resulting in an estimated 123 fatalities. The most common form of targeting is direct attacks, with 168 events, followed by property destruction, with 31 recorded events.

This piece focuses on the targeting of municipal-level officials – the main victims of violence against local officials in Brazil. While the complexity of the conflict environment and gaps in the Brazilian media landscape mean that the majority of these events are attributed to unidentified perpetrators, the trends point to several drivers behind this violence. Drawing on the geographic distribution and temporal variation of violence targeting local officials, this report explores the influence of organized criminal groups in local governance and electoral competition between municipal politicians as key drivers of this violence.

Organized Crime Connections with Local Officials Drive Threat of Violence

In order to continue holding hegemony in the areas where they operate, Brazil’s organized criminal groups establish mutually beneficial networks of financial and political sponsorship with state officials.2Ianara Garcia, ‘Candidato a vereador em MT alvo de operação foi escolhido por quadrilha de Fernandinho Beira-Mar, diz PF’, G1, 16 November 2020 In more extreme cases of collaboration, organized crime becomes part of the administrative apparatus, allowing them to engage in illegal endeavors undisturbed. Police militias in Rio de Janeiro, which are organized primarily by state law enforcement agents and local officials, are one such example. These militias were ostensibly created with the aim of fighting crime and drug trafficking, though they also engage in racketeering, extortions, and smuggling (for more on police militias, see this ACLED report).

Areas under the control of militias and organized criminal groups have thus become electorally significant, leading to the establishment of collusive relationships with local politicians. This dynamic further blurs the line between organized crime and local politics, as they progressively moved into exploiting the same illegal activities as drug traffickers.3Clarice Ferro and Inara Chagas, ‘Milícias no Brasil: como funcionam?’, Politize, 28 August 2017 These dynamics were at the heart of the killing, in 2022, of former Rio de Janeiro councilman Jerônimo Guimarães Filho, who was one of the founders of the Justice League (Liga da Justiça), the most notorious police militia in Rio de Janeiro state.4Maria Fernanda Firpo, ‘Jerominho: quem é o ex-vereador e fundador de milícia executado no RJ,’ Metrópoles, 4 August 2022

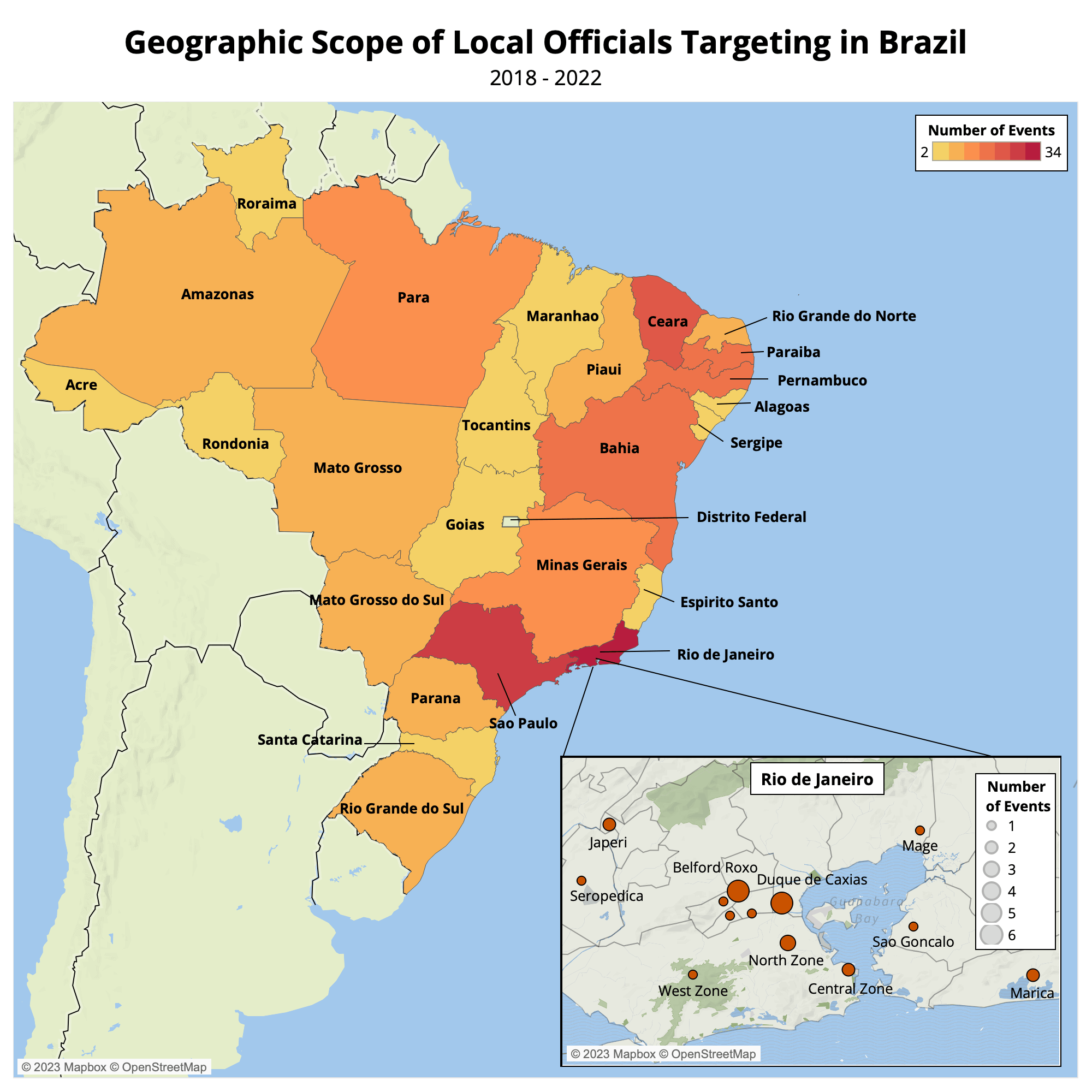

Not surprisingly, the highest levels of violence targeting local government officials have taken place in Rio de Janeiro and Sāo Paulo states (see map below), where ACLED records 34 and 28 events, respectively, from 2018 to 2022. Not only do these states experience the highest levels of political violence in Brazil, but they are also home to the most significant organized crime groups in the country. The Red Command (Comando Vermelho, or the CV) and the First Capital Command (Primeiro Comando da Capital, or the PCC) were founded in Rio de Janeiro and Sāo Paulo, respectively.

These criminal organizations particularly thrive in zones of social and political marginalization, such as the North Zone and West Zone of Rio de Janeiro, where they can enforce de facto authority on a local level. In these zones, they can decide which parts of the city people are allowed to go to, and charge illegal fees for access to common services – all while colluding with government officials to secure impunity.5Ruhani Maia, Victor Muniz, ‘Tribunal do tráfico ordena expulsões e mortes’, Gazeta Online

In these areas, organized crime groups may use violence to make way for their financial ambitions and to silence local officials if expectations are not met.6Marcelo Godoy, ‘PF vai catalogar vereadores eleitos com dinheiro do crime’, Estado de São Paulo, 27 October 2020; Rafael Nascimento D’Souza, ‘Vereador de Araruama foi assassinado por traficantes de Duque de Caxias, diz polícia,’ Extra Globo, 9 September 2019 The notorious case of Councilwoman Franco illustrates the silencing of voices opposed to police brutality and the presence of police militias in impoverished communities in Rio de Janeiro. Investigations associate her killing with the Escritório do Crime police militia, a group of hitmen consisting of former military police officers.7Ana Helena Paixão, ‘Entenda a conexão do Escritório do Crime com a morte de Marielle, Metrópoles, 23 January 2019

ACLED also records high levels of such violence in the northeastern states of Paraíba, Bahia, and Pernambuco. Here, the CV and the PCC have forged alliances with local gangs, such as Bonde do Maluco and Comando da Paz in Bahia, to dispute the control of drug trafficking routes and access to new markets.8Leandro Machado, ‘A ascensão da Okaida, facção criminosa com 6 mil soldados na Paraíba’, BBC News Brasil, 18 April 2019; O Tempo, ‘Facção ligada ao PCC transforma ilha na Bahia em bunker,’ 27 May 2023; Bruno Wendel, ‘Comando Vermelho se estabelece na Bahia a partir de aliança com o CP ‘ Jornal Correio, 25 September 2020 Acts of violence against local officials in these states are allegedly linked to drug trafficking activities.

Notably, in the north and northeast regions of the country, drug trafficking groups often engage in acts of vandalism and destruction of public property to intimidate local officials in response to the enforcement of stricter public security measures.9Carlos Madeiro e Herculano Barreto Filho, ‘Ataques no RN: facção usa tática terrorista, enfrenta PCC e desafia Estado,’ UOL, 15 March 2023 In 2018 and 2019, the PCC attempted to burn down city halls in small cities of Minas Gerais and Rio Grande do Norte states to draw attention to poor living conditions in detention facilities, while also calling for the resignation of prison directors and security deputies.10Arthur Stabile, ‘Bilhete indica que PCC teria ordenado série de ataques em Minas Gerais e Rio Grande do Norte,’ El País, 6 June 2018 Similarly, in 2018 several public buildings were shot at or set on fire in Fortaleza and nearby cities in Ceará state as a response from the CV to the death of fellow gang members in clashes with police.11Emanoela Campelo de Melo, ‘Chefe do CV na Aerolândia ordenou ataque a viatura da PM’, Diário do Nordeste, 4 August 2018

National Electoral Contention Puts Local Officials at Risk

Violence targeting local officials spiked with the municipal elections in 2020. ACLED records at least 66 violent events targeting local officials in 2020, an increase of 27% compared to the year prior (see graph below). At least 96 events of violence were perpetrated against candidates, 11 of whom were serving or former local officials. Notably, violence increased in May, coinciding with the registration of candidates and the beginning of electoral campaigns, and in October and November, just before the first voting round on 15 November. Many of these attacks turned deadly, with at least 32 recorded local officials killed in 2020 alone, almost twice the number recorded in 2019.

Several of these incidents occurred in the lead-up to the 2020 municipal elections.12Felipe Borba et al., ‘Violência política e eleitoral nas eleições municipais de 2020,’ Revista Brasileira de Ciências Sociais, 37 (108) Attacks were instigated or carried out by local politicians who saw their targets as a threat to their political dominance or an obstacle to getting elected or re-elected. For instance, in Novo Acordo municipality, Tocantins state, a deputy hired hitmen to kill the mayor over money siphoned off public bids. Likewise, Councilman Ronaldo Batista from Funilândia municipality, in Minas Gerais state gave orders to kill another councilman, Hamilton de Moura, as he intended to take over the leadership of a union.13Ana Laura Queiroz, ‘STJ nega soltura de ex-vereador de BH acusado de mandar matar sindicalista,’ Estado de Minas, 29 June 2022

Despite not having a formally identified perpetrator, the circumstances of other attacks also suggest a political trigger. In Alto Paraíso municipality, Rondônia state, unknown individuals abducted and tortured a councilor, demanding he stops supporting a mayoral candidate.14O Liberal, ‘Vereador é sequestrado e torturado para abandonar campanha,’ 10 November 2020 Elsewhere, in Jandira municipality, São Paulo state, an unknown assailant fatally shot at point blank a former councilman, who was a corruption whistle-blower – suggesting a case of political revenge.15Kelly Miyashiro, ‘Ex-vereador do PT, Zezinho é morto a tiros em Jandira; polícia investiga,’ Veja, 29 October 2022

In 2021, political violence targeting local officials remained high, amid increasing political animosity in the country as officials struggled to coordinate an effective response to COVID-19. Then-President Bolsonaro turned a health crisis into an ideological dispute and encouraged his allies to do the same. Among other attempts to dilute the severity of the pandemic, Bolsonaro actively sought to block state and municipal officials from following guidelines from the World Health Organization.16Ferraz Junior and Vinicius Botelho, ‘Polarização e pré-campanhas eleitorais marcam ano político’, Jornal da USP, 23 December 2021 Administrative confusion led to varied responses to the pandemic and political polarization, and the opposition set up a parliamentary committee in the Senate to investigate federal officials for negligence.17Lisandra Paraguassu, ‘Brazil pandemic probe places current, ex-officials “under investigation”‘, Reuters, 18 June 2021 That polarization trickled down to lower levels of government, resulting in high levels of violence in 2021 as well. In Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul state, a group of Bolsonaro supporters who opposed a bill regarding mandatory coronavirus vaccination invaded the Municipal Chamber and physically assaulted several left-wing councilors.18Ivan Longo, ‘Grupo antivacina invade Câmara de Porto Alegre, agride vereadores e exibe suástica nazista; veja vídeos’, Revista Fórum, 20 October 2021

Levels of violence targeting local officials fell in 2022, as Brazil faced one of the most polarized general elections in recent political history. Notably, though, while state officials, candidates for Congress, and state deputies running for re-election all faced violence, the majority of events in 2022 – at least 42 – targeted municipal-level administrators. While individual motives behind these attacks may not be explicitly tied to the electoral cycle, the broader trend suggests that those operating at the local level bear the greatest burden of political competition, even when it occurs at the national level.

Threats Persist Amid Political Developments

ACLED data suggest that the targeting of local officials in Brazil is more pervasive at the municipal level in all scenarios, and heightened during local elections. In the first quarter of 2023, the number of violent events was in line with what was observed in the last two years. Yet, several key factors are likely to drive violence against local government officials in the next year: heightened tensions stoked by national politics as well as the 2024 municipal elections, and the collusive relationship between organized criminal groups and some local authorities who are most exposed to these illicit activities.

The Supreme Court of Justice is investigating the roles of prominent politicians in instigating the demonstrations that followed general elections and the storming of the National Congress, the Supreme Court, and the Planalto Palace in Brasília on 8 January 2023.19Flávia Maia, ‘STF já soma 7 novos inquéritos sobre atos antidemocráticos’, JOTA, 23 January 2023 Among them is the Governor of the Federal District Ibaneis Rocha, who was suspended from office for failing to protect federal institutions. A mixed parliamentary commission of inquiry was also set up in Congress to investigate the attacks.20Leticia Mori, ‘CPMI de 8 de janeiro: quem é quem na comissão e o que esperar’, BBC News Brasil, 29 May 2023 Since these investigations aim to identify organizers and financiers of the riots, they may lead to disturbances in already established alliances of political and financial support to local officials, with the potential to drive further violence.

The upcoming municipal elections in 2024 are likely to amplify existing party tensions and exacerbate local political rivalries.21Felipe Borba et al., ‘Violência política e eleitoral nas eleições municipais de 2020,’ Revista Brasileira de Ciências Sociais, 37 (108) As seen in previous electoral cycles, the start of electoral campaigns are likely to unleash heightened levels of violence amid competition for local office. Ongoing impunity and the rarity of prosecution for attacks on local officials has generated a climate conducive to the use of violence by local elites to settle political disputes and favor their interests during the next municipal elections.

Moreover, ongoing investigations on the interference of organized crime in the latest election in the states of Piauí22Hugo Marques, ‘MP investiga interferência do crime organizado nas eleições no Piauí,’ Veja, 10 March 2023 and Rio de Janeiro23O Dia, ‘Investigação da PF e MP aponta ligação de Vandro Família ao crime organizado em eleição 2022,’ 28 September 2022 points to continuous involvement of gangs and militias in the elections. Lula’s administration launched a federal operation to curb illegal mining, driving thousands of miners out of the Amazon and causing an outbreak in violence.24Leonardo Martins and Lucas Borges Teixeira, ‘Com militares, governo começa retirar 15 mil garimpeiros de área yanomami,’ UOL, 6 February 2023 The illegal miners are associated with the PCC, and continue to confront state forces in the Amazon region.25Fabíola Perez, ‘Ações do PCC fortalecem permanência de garimpeiros na Terra Yanomami,’ UOL, 3 May 2023; Rafael Moro Martins and Ana Magalhães, ‘‘Narcogarimpo’ desafia o governo no território Yanomami,’ Sumaúma, 16 May 2023 During the last elections, at least 70 candidates were linked to illegal mining, most of whom were connected to former president Bolsonaro.26João Gabriel & Lucas Marchesini, ‘Garimpo e mineração de ouro lançam mais de 70 candidatos no país com impulso de Bolsonaro,’ Folha de S. Paulo, 19 September 2022 These trends point to the enduring threat posed by organized criminal actors in the political sphere, thereby heightening the risk of violence in the upcoming elections.

Visuals in this report were produced by Ana Marco and Ciro Murillo