Q&A with

Clionadh Raleigh

ACLED President & CEO

Elections for a new president in Zimbabwe had chaotic moments and were heavily biased in favor of incumbent Emmerson Mnangagwa and his ruling ZANU-PF party. But in this Q&A, ACLED President Clionadh Raleigh argues that, contrary to outside impressions, the data point to a largely peaceful situation. Nevertheless, she says, the 80-year-old Mnangagwa’s near-certain win will not save this “competitive autocracy” from looming, inner-party struggles for power.

ACLED rigorously monitors political stress events all over the world. How much violence was there around Zimbabwe’s 23 August 2023 election?

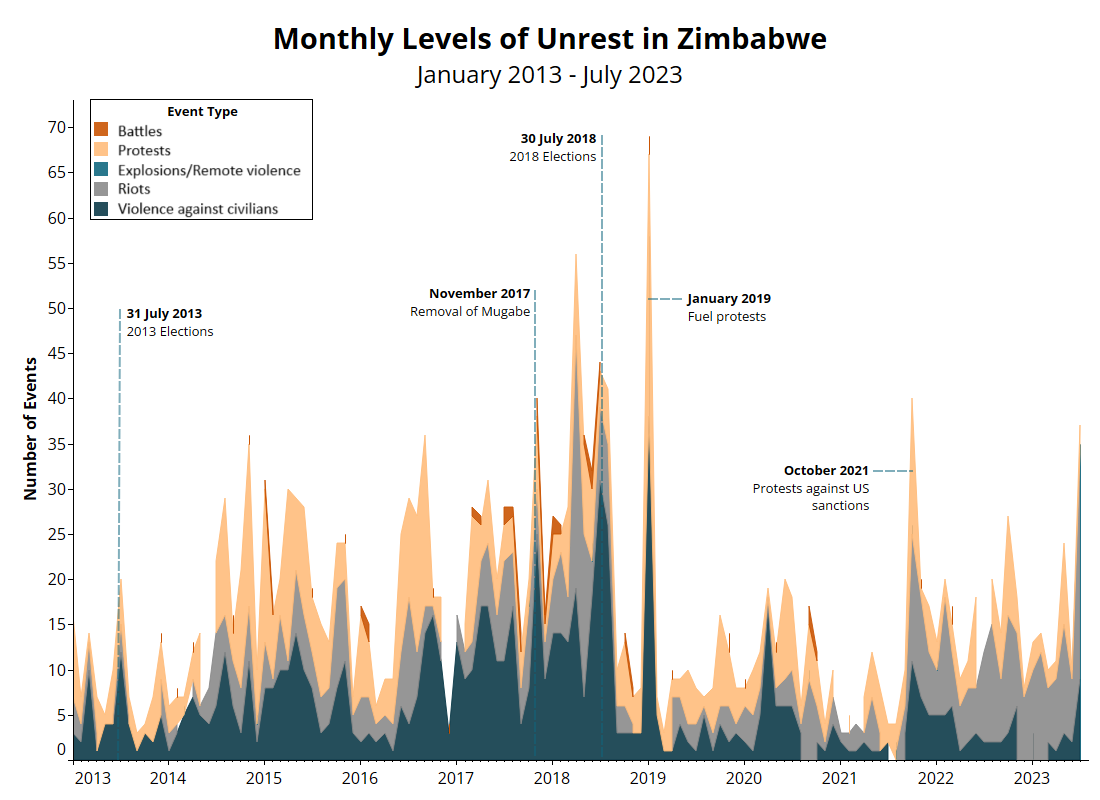

Very little. In relative terms, Zimbabwe is safe as houses. ACLED data show an uptick in political violence incidents in July, ahead of the elections. But over the past year there was a weekly average of just four events. That’s about one-fifteenth as many as, say, Somalia, an African country of the same population size that is mired in conflict. And this annual average is less than one-hundredth of the crisis events experienced by some of the world’s most conflict-stricken countries like Ukraine, Myanmar, Israel/Palestine, and Mexico.

Most incidents of violence occur in very densely populated areas, which, in one-party states, are often strongholds of the opposition. So what you have effectively is street gangs going at it alongside some heavy-handed activity by the police, although, to be honest, in Zimbabwe, the police are not the most efficient at it. Zimbabwe is a very political place. There are lots of rallies all the time, all kinds of engagement on the street, political parties springing up. People talk about politics openly on the phone. It’s almost a sport compared to truly totalitarian countries.

Especially in African countries with a history of friction with the West, a specter of violence always seems to be lurking when we talk about elections. But if the government is organized, all the cheating has been done early. So, any violence tends to be in reaction to the vote, in this case perhaps rioting when the ruling party announces that it has won. But I would say that fears of violence in Zimbabwe are always far greater, typically, in people’s minds in the West than they are in-country. They’re exaggerated. This week in the United States, more people were killed in a bar than were killed during this entire election period in Zimbabwe. And yet, those places are spoken about in very different ways.

What’s your take on the conduct of the elections? Do you think the voting delays amounted to serious irregularities?

The controversy over the late arrival of some ballot papers was a storm in a teacup. It appeared to affect a small amount of voting districts.

You started using ACLED data more than a decade ago to inform your academic work on how ZANU-PF party structure incentivizes violence. The late, long-serving leader Robert Mugabe talked of his colleagues having “degrees in violence.” Is this dynamic disappearing?

ZANU-PF is much stronger than the opposition, public life is quite tightly controlled, and there is low-level consistent repression without overt violence. They have this old-school idea that sometimes you’re going to have to break some legs to stay in power. They see these problems with the opposition as ones of inconvenience, that you deal with decisively, either with the police or with thugs. To be blunt, there is no need for ZANU-PF to engage in very significant, national-scale violence. They are content to keep fatality rates very low, because they think eventually the Western world will recognize that this is not so bad. That strategy isn’t working yet, but that’s where they’re at with it.

Violence is in fact less a result of repression of the opposition, but, like a lot of one-party state dictatorships, more often it originates within the ruling party and within government structures, which are modelled on party structures. Conflict is a competition about who is going to be in charge. Our data show that the poor and excluded are not the ones most likely to create violence. It is very clear that often the wealthiest areas, the ones with the most representation, see the most conflict. It is generated by people who have something to lose. ZANU-PF’s real worry is internal dissension and the ability of rivals in the elites to create a gang or a militia. So they police that very much internally.

For instance, when you look at the geography of violence for 2008, it was mostly in the run-off round. ZANU-PF zeroed in on areas where it is usually strong and where people hadn’t voted for Robert Mugabe in the first round, trying to reverse what you could call traitor votes. These areas then reported very high rates of Mugabe support in the run-off election. This turns the typical argument of where violence happens during elections on its head.

What other insights have you gained from ACLED data?

The highest spike in our Zimbabwe data was around the January 2019 fuel price riots. This is not out of line with what we saw in a lot of places around the world in 2019. But the rise in the cost of living was particularly bad in Zimbabwe and these demonstrations were very, very large. After initially high hopes in Mnangagwa as someone very smart and pretty reasonable, if brutal, there was a general sense that he had missed an opportunity, not been a good steward of the economy, and that things were going in the wrong direction. There’s still a general sense of malaise that he can’t fix the economy. The country still has the second highest rate of inflation in the world. But I think the fuel price situation marked the high-point of the issue of corruption. He certainly claims things are getting better.

Given these relatively peaceful elections and a clear outcome, would you call Zimbabwe a democracy?

No, not even an illiberal democracy. It’s a competitive autocracy, an autocracy with an election. The game seems to be to reach the lowest level of electoral participation that the international community demands. The West is constantly trying to facilitate elections, even though such polls just strengthen these one-party states.

Many African states are competitive autocracies with a one-party state that is not about to lose power: think of Ethiopia, Zimbabwe, or Uganda. Even South Africa and Kenya share these characteristics to some extent. Often these parties constructed the regime after a conflict or in the post-colonial period. In Zimbabwe, the situation is that ZANU-PF cannot even conceive of a period in which they’re not in power.

How many linkages do you see between what’s been happening in Zimbabwe and the rest of the continent, especially given the civil wars, the expansion of violent groups like the Islamic State, and a series of coups in recent years across the Sahel?

One way to put it might be that Southern Africa never gets that wild. Some suggested that after the Islamic State won a foothold in Mozambique in 2017, the group’s violence would spread to Malawi. It didn’t. Then they said it’s going be Zimbabwe, but it didn’t get close, nor to South Africa and Tanzania. It’s not an area that is like ripe for these sorts of large conflicts, it doesn’t have the right ingredients. Partially it’s because there are relatively homogenous populations there, few religious antagonisms, people feel well represented and have better economic growth. There are very few vehicles for infiltrators to jump onto. Granted, in Zimbabwe’s case, growth is more of a potential than something actual, but the country is stable enough.

As such competitive autocracies wax and wane, you’ve described cycles of accommodation, consolidation, factionalism, and crisis. What phase is Zimbabwe currently in?

After he took power in 2018, Mnangagwa needed to consolidate and accommodate. He brought in military officers and left a lot of the Mugabe-era elite at the top. Then he went into a different phase and started to get rid of the power bases of others because he was now stronger than they were. He is no longer so accommodating.

In the short term, our forecasting tool, the Conflict Alert System, or CAST, is predicting that in the coming months political stress events could double to eight per week. There will be a reaction, a small spike in the data, probably in the main cities of Harare and Bulawayo, as with other elections. These could be mob violence, rioting, or attacks on government offices. If there is a run-off election, then you would probably get a big spike as ZANU-PF enforces discipline, mainly among its own voters. But a run-off is almost certainly not going to happen.

In the longer term, we will move into a very different stage. The state is set up to benefit the elite, but less and less is trickling down these days. On the government side, Mnangagwa has said this is his last term. There’s a hunger for power and there’s going to be a lot of maneuvering to establish who’s going to be his successor at the eventual party congress. On the opposition side, things are not going well. I would be very surprised if Nelson Chamisa runs again as head of the Citizens Coalition for Change (CCC), because he’s bad at it. This combination of succession battles could herald a dangerous phase. In ZANU-F, the new generation can be brutal. They’ll lie, cheat, and steal to get whatever they want.

At the same time, people far away may not realize that Zimbabwe is a wonderful place. Its profile has a lot of similarities to Ireland in Europe, having an educated, politically aware, stable, calm population with a lot of potential. It is being held back both by domestic struggles and by international impressions about its ability to develop under this highly corrupt regime. While it’s a tragedy about how Zimbabwe is being constrained by the machinations of ZANU-PF, they haven’t by any means managed to ruin the country yet.

Clionadh Raleigh was speaking to ACLED Advisor Hugh Pope.