Actor Profiles:

Islamic State Mozambique (ISM)

30 October 2023

This Actor Profile was produced as part of the Cabo Ligado project, ACLED’s Mozambique conflict observatory with Zitamar News and MediaFax. For more Mozambique data and analysis, visit Cabo Ligado here.

Introduction

The group now known as Islamic State Mozambique (ISM) emerged as an armed group in October 2017, known locally both as al-Sunna wal-Jamma (ASWJ) for its ideological underpinnings and al-Shabaab for its extensive use of violence. Despite its rapid growth up to 2021, it has been one of the Islamic State’s (IS) most opaque affiliates. ISM was first recognized as a distinct IS province in May 2022, having previously been under the broader Islamic State Central Africa Province (ISCAP) organization from as early as 2018. The origins of ISM lie in East African Salafi-jihadist networks that reached into northern Mozambique as early as 2007.1Eric Morier-Genoud, ‘The Jihadi Insurgency in Mozambique: origins, nature, and beginning,’ Journal of Eastern African Studies, 14/3, 2020, pp. 396-412 This profile examines the group’s origins and its development over the past decade. It uses ACLED and other data to assess the group’s objectives and consider its future prospects.

Origins

ISM arose from Wahhabi-inspired religious thinking that challenged mainstream Islamic leadership, traditional norms, and state legitimacy. In its earliest form, the group developed as young, radical, and often well-traveled figures preached against state involvement in Muslims’ lives, condemned mainstream religious leadership, and challenged everyday social norms. Radicalized groups willing to take up arms and established in this way in mosques and madrasas would go on to be the core of the insurgency.2Saide Habibe, Salvador Forquilha, & João Pereira, ‘Islamic Radicalisation in Northern Mozambique: the case of Mocímboa da Praia,’ 2019, Cadernos IESE, No 17/2019 The formation of such groups occurred across Cabo Delgado province in the 2010s. Mocímboa da Praia was the epicenter, but these groups were also found in Balama and Chiure in the southwest and south,3Eric Morier-Genoud, ‘The Jihadi Insurgency in Mozambique: origins, nature, and beginning,’ Journal of Eastern African Studies, 14/3, 2020 Macomia on the coast, Nangade in the north of the province, and Niassa province to its west.4Sergio Chichava, ‘The First Signs Of “Al Shabaab” In Cabo Delgado: some stories from Macomia and Ancuabe,’ Ideias, Boletim No. 129e, 8 May 2020; Salvador Forquilha & João Pereira, ‘After All, It Is Not Just Cabo Delgado! Insurgency dynamics in Nampula and Niassa,’ Ideias 138e, 11 March 2021

This process of organization, the underlying ideology, and its challenge to accepted norms and authorities led to conflict within communities and between the group’s adherents and the state in the years prior to the insurgency. In Chiure in 2016, for example, it led to three days of conflict. While this conflict was initially within the Muslim community over authority with mosques, it was followed by a clash between sect adherents and police.5Eric Morier-Genoud, ‘The Jihadi Insurgency in Mozambique: origins, nature, and beginning,’ Journal of Eastern African Studies, 14/3, 2020

Outside Cabo Delgado, similar processes of organization in Muslim community institutions were followed by the formation of armed groups, some of which had connections to Cabo Delgado and elsewhere in East Africa. This process was seen in neighboring Tanzania’s Tanga region between 2012 and 2017, where such groups had connections to Somalia.6Peter Bofin, ‘Tanzania and the Political Containment of Terror,’ Hudson Institute, 24 January 2022 In Kibiti district of Tanzania, south of Dar es Salaam, mobilization in radical mosques and madrasas of hundreds of youth culminated in a proto-insurgency in 2015, which carried out two years of targeted killings against the ruling party and local government officials.7John Jingu, ‘The Flurry of Crimes in Kibiti and Rufiji and the Quest for Effective Early Warning and Response Mechanism,’ The African Review, 45/1, 2018 The proto-insurgency was eventually put down in 2017 by Tanzania’s security forces, but key leaders of the insurgency fled to both northern Mozambique and northeast Democratic Republic of Congo.8Erick Kabendera, ‘Militants in Mozambique Could Be Tanzanian,’ The East African, August 11, 2018; European Institute of Peace, ‘The Islamic State in East Africa,’ 2018

Parallel to the seeding of the insurgency was the emergence of Mozambique’s first liquefied natural gas (LNG) project near Palma town after considerable natural gas resources were discovered offshore in 2010 by the oil company Anadarko. Development of the LNG project was quick by international standards. By 2014, a decree law was passed to facilitate the project. By 2017, plans were being made to resettle affected communities, with approval of the project’s development plan coming in 2018. In 2019, two years into the insurgency, France’s TotalEnergies acquired Anadarko, and announced the project’s Final Investment Decision the same year.9TotalEnergies, ‘Total Closes the Acquisition of Anadarko’s Shareholding in Mozambique LNG,’ 30 September 2019 The fast-developing project would soon become a target of the group locally, the subject of IS rhetoric internationally, and the clearest demonstration of the group’s threat to the state.

Activity and Area of Operation

Years of organization in northern Mozambique, regional support networks, and an emerging LNG project would each factor into the shape of the insurgents’ activities, and the national and international response. The strong organization of insurgent groups and regional support networks enabled the rapid growth of the insurgency until 2019. The growth of the insurgents was followed by almost two years of consolidation between 2020 and 2021. During this time, the group did not control the province but ISM activity made it ungovernable. External interventions from Rwanda Security Forces (RSF) and the Southern African Development Community Mission in Mozambique (SAMIM) severely disrupted the group. Despite the setbacks, ISM weathered these offensives until November 2022. Since this time, political violence carried out by the group has steadily decreased.

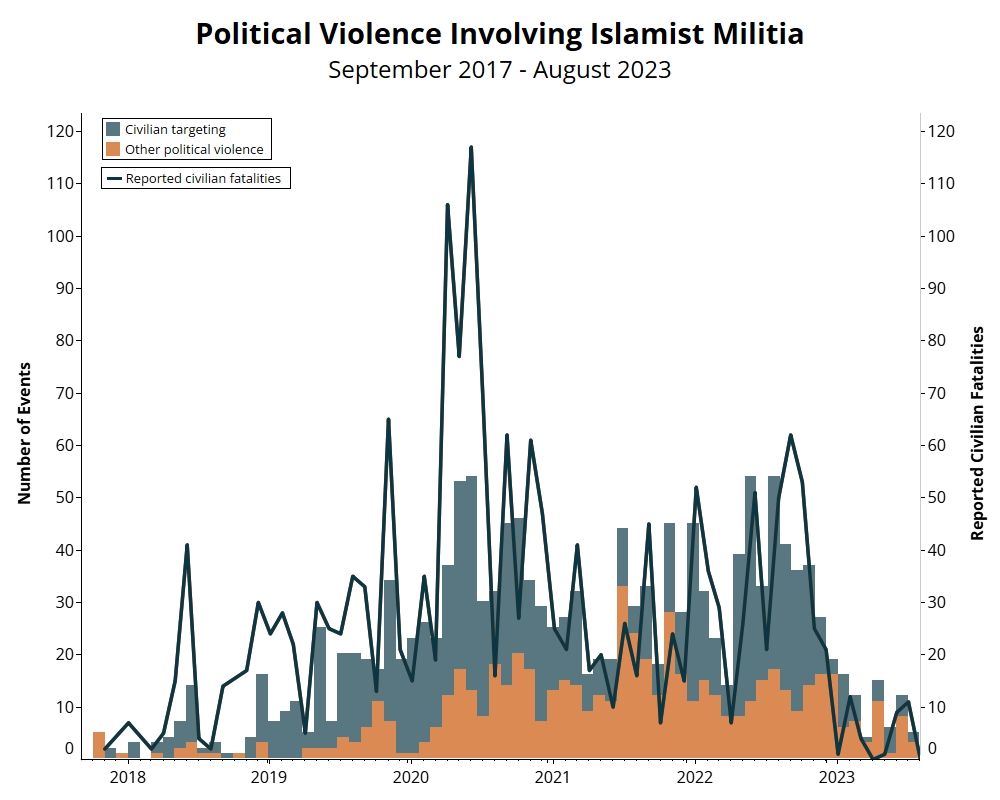

Growth: 2017-19

In the insurgency’s early years, the group was marked by a lack of a clear identity. The names ‘ASWJ’ and ‘al-Shabaab’ signaled violent jihadist ideology, but public messaging from the militants themselves was rare. An early video statement from January 2018 showed four young men addressing their “Mozambican brothers” and endorsing “Quran as law.”10PortalMoz News, ‘Veja o vídeo dos atacantes de Mocímboa da Praia planejando mais ataques,’ 28 January 2018 Nevertheless, the targeting of civilians by insurgents obscured any political objectives. From 2017 until the end of 2018, ISM had been involved in 66 incidents of political violence, of which almost 73% were targeting civilians. Over 80% of those incidents took place in the insurgents’ heartland of Macomia, Mocímboa da Praia, and Palma districts, with further activity in Nangade, Pemba, Muidumbe, and Quissanga districts. The targeting of civilians continued through 2019, accounting for 80% of annual political violence events involving ISM, as the group spread geographically. Over the course of 2017, 2018, and 2019, at least 464 civilians were killed by the group (see graph below).

Consolidation: 2020-21

If ISM’s political objectives were obscured, they first became clearer when formal affiliation of the insurgents with ISCAP was issued through IS media channels in June 2019. ISCAP, with the Allied Democratic Forces (ADF) operating in DRC, at its center, had been acknowledged by IS in 2018. Relations between ADF/ISCAP with Cabo Delgado’s insurgent group predated June 2019 considerably. The United Nations Group of Experts has presented evidence of movement between ADF and Cabo Delgado’s insurgent group as early as 2017.11Group of Experts on the DRC, ‘Final report of the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo,’ S/2023/431, 13 June 2023 However, affiliation with IS sharpened the Cabo Delgado insurgents’ ideology and would give access to both technical assistance and external financial support. This was clear in the subsequent coherence between operational targeting by the insurgents, IS analysis of the conflict, and local messaging within Cabo Delgado. Together, these three factors positioned the group with a clear ideology, challenging the state, focusing on local grievances, and targeting the LNG project.

In late 2019, IS had tasked IS Somalia, based in Puntland, to coordinate support across the region through its Karrar hub.12Caleb Weiss, Ryan O’Farrell, Tara Candland, and Laren Poole, ‘Fatal Transaction: The Funding Behind the Islamic State’s Central Africa Province,’ GW Program on Extremism and Bridgeway, June 2023 Tactical training was provided reportedly as early as 2020.13UN Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team, ‘Twenty-eighth report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team submitted pursuant to resolution 2368 (2017) concerning ISIL (Da’esh), Al-Qaida and associated individuals and entities,’ S/2021/655, 21 July 2021 There is also evidence of payments to Mozambique as early as 2020, through the remittance of money raised in Somalia and South Africa and sent to Mozambique and DRC through agents in Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda.14Group of Experts on the DRC, “Final report of the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo,” S/2023/431, 13 June 2023

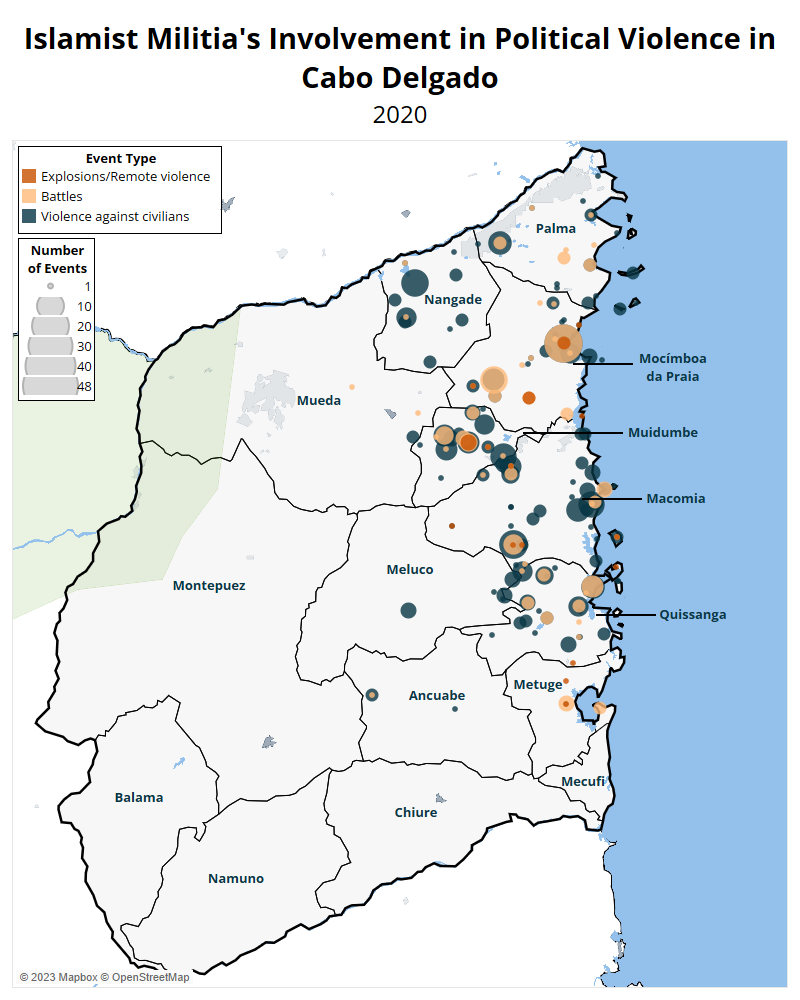

The impact of IS support from Somalia became apparent in 2020 and 2021, permitting ISM to increase operations and allowing the insurgency to reach the peak of engagement in political violence events in June 2020. Insurgents pointedly targeted urban centers, seized control of Mocímboa da Praia town, and twice threatened the LNG project at Palma. By the end of 2020, their operations were concentrated in five districts in the north of the province and along the coast, with limited engagement as far south as Ancuabe and Metuge districts.

The authorities were, by this time, losing control of the north, with insurgents controlling the N380 and N381 roads. The former connects the provincial capital Pemba to Cabo Delgado’s northern districts, while the former connects the northern districts to Tanzania. In March 2020, Quissanga and Mocímboa da Praia district headquarters were briefly occupied. In April, Muidumbe headquarters was occupied,15Mozambique News Reports & Clippings, ‘Insurgent Push in Cabo Delgado,’ 9 April 2020 and in May, it was the turn of Macomia headquarters. These attacks culminated in August 2020, when the insurgents asserted control over Mocímboa da Praia town, expelling government forces. They went on to control the town for 12 months, until the arrival of the RSF the following year. The year ended with a series of attacks in Palma district, culminating in an attack on Quitunda on 1 January 2021, a village located on the perimeter of the LNG project that was built to house people evicted to make way for the project. The attack led to TotalEnergies ordering the evacuation of staff the following day (for more, see the following Cabo Ligado Weekly Updates: 25-31 May 2020, 10-16 August 2020, and 4-10 January 2021)

In all of these attacks, insurgents targeted state institutions such as garrisons, police stations, health centers, and schools. They also regularly targeted neighborhoods dominated by state employees and the homes of prominent figures in the ruling Frelimo party or business people.16João Feijo, ‘Do Impasse Militar Ao Drama Humanitário: Aprender Com A História E Repensar A Intervenção Em Cabo Delgado’ Observatório do Meio Rural, 7 July 2020 This shift to targeting state institutions was also reflected in a marked reduction in the proportion of times they targeted civilians. While civilian fatalities peaked in 2020 – reaching over 650 annual reported deaths amongst civilians – civilian targeting events comprised a smaller proportion of the overall political violence involving ISM in 2020 compared to previous years.

The shift in operations and targeting was indicative of an increased interest in taking on the state and undermining LNG investment. It reflected an analysis of the conflict presented by IS through its al-Naba newsletter in July 2020, which highlighted the role of “Crusader oil companies,” unspecified historical grievances, and abuses by the security forces against civilians during the conflict as factors justifying the conflict.17Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi, ‘Islamic State Editorial on Mozambique’, Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi website, 3 July 2020 Locally, a short statement by ISM filmed at the District Administrator’s office in Quissanga in March 2020 succinctly expressed its objective of taking on the state. “We don’t want the Frelimo flag … you can see that flag that we are using,” the insurgents said, under an IS flag.18E. Morier-Genoud ‘ #Breaking: insurgents in #CaboDelgado #Mozambique make a video statement (the second since 2017). Speaker says they want sharia rule and #ISIS#EI flag – not Frelimo flag,’ 26 March 2020

Dispersal and Contraction: 2021 to date

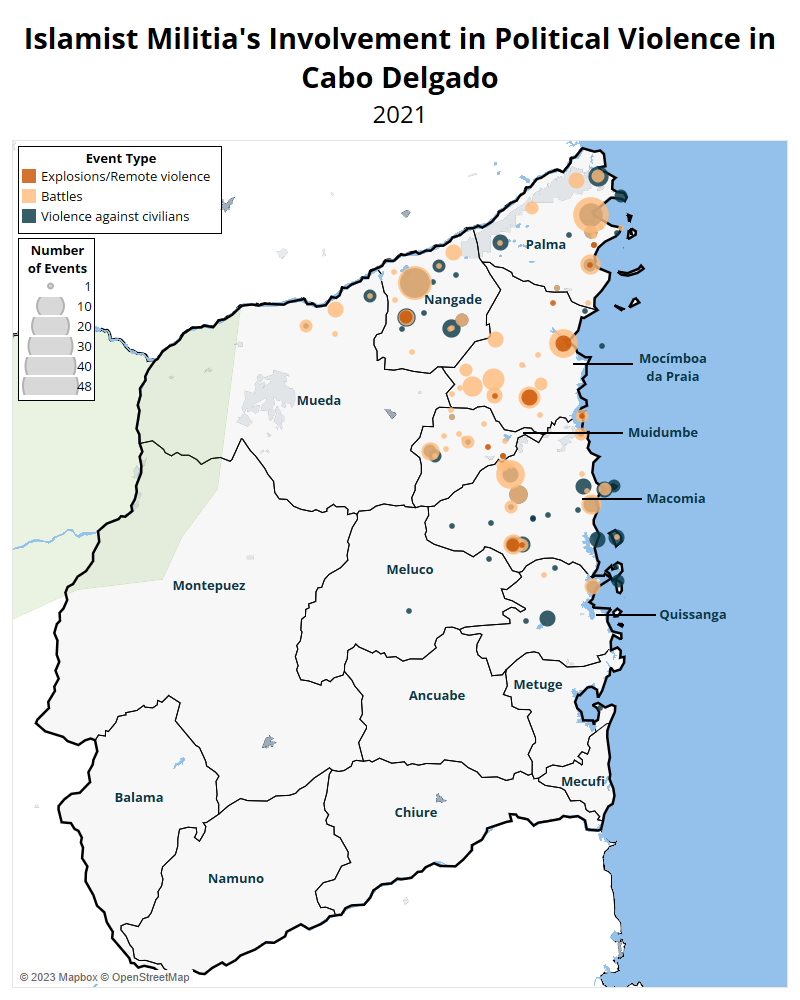

The al-Naba editorial in July also noted the likelihood of international intervention, which by that time was an ongoing agenda item for Southern African Development Community (SADC) leaders, with South Africa having started planning military support for Mozambique by at least May that year. The insurgents’ attack on Palma town on 24 March 2021 presented a real threat to the LNG project, and precipitated intervention from both SADC and Rwanda in July 2021.

Reflecting the importance of the LNG project to both the Mozambican government and to the insurgents, the RSF deployed in Palma and Mocimboa da Praia districts. The LNG project itself is situated in Palma district, while the port town Mocímboa da Praia is critical to the project as the commercial center of the province’s northern districts. Both districts had been closely targeted by the insurgents from the first day of the conflict. The RSF successfully gained control of both district headquarters by August 2021, less than two months after the initial RSF deployment.

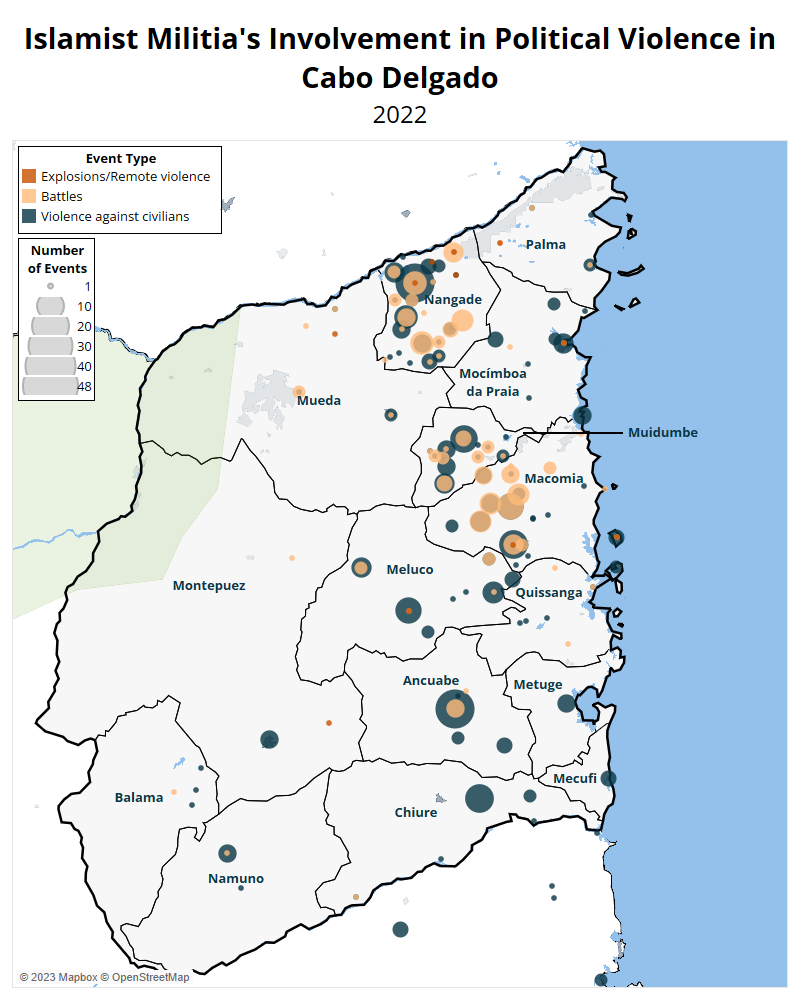

SAMIM deployed more slowly, covering Nangade, Macomia, Mueda, and Muidumbe districts. However, a lack of coordination between the RSF and SAMIM forces allowed the insurgents to disperse. By the end of 2022, ISM had been involved in political violence events in new districts, and 16 of Cabo Delgado’s 17 districts overall, as well as parts of Nampula and Niassa provinces (see maps below).

ISM maintained its resilience to state and international forces by successfully shifting to operating in small mobile groups and, at the same time, partially relying on external tactical support through coordination with the IS Karrar hub in Somalia. The group also became more technically sophisticated itself, as shown by its first successful deployment of an improvised explosive device (IED) in September 2021.

The insurgents’ dispersal strategy was initially successful. In 2022, insurgents engaged in 437 incidents, compared to 432 in 2020 when they were approaching their peak. Four districts in the south – Balama, Chiure, Montepuez, and Namuno – saw armed actions by insurgents for the first time in 2022. ISM could not maintain its expansion of operations, however, and the southern districts have not seen activity by insurgents since February 2023.

Its emerging technical sophistication and tactical ability to withstand the first months of RSF and SAMIM operations may have prompted IS to recognize its Mozambique affiliate as a separate province. The group began operating as ‘Islamic State Mozambique Province’ in May 2022, identifying itself as such in its communications through IS media channels, as well as in its direct messaging in Cabo Delgado communities. Like its incorporation into ISCAP, this was done with little fanfare, with IS issuing a claim on 9 May 2022 for an operation in its ‘Mozambique Province.’

The group’s recognition as a distinct province was followed by an overt shift in its approach to civilians. Handwritten notes left in communities, firstly in October 2022, urged cooperation from communities, including non-Muslims, in return for which they would be unharmed. This approach is thought to have followed a direction given by IS at a meeting or meetings attended by senior ISM figures in DRC in mid-2022.19Centre de Jornalismo Investigativo, ‘Cabo Delgado 2017-2022: Um Quinquénio de Terror,’ 5 October, 2022 The high rate of civilian deaths at the hands of ISM in 2022 – over 430 – indicates that the threat to non-cooperating communities contained within this approach was real.

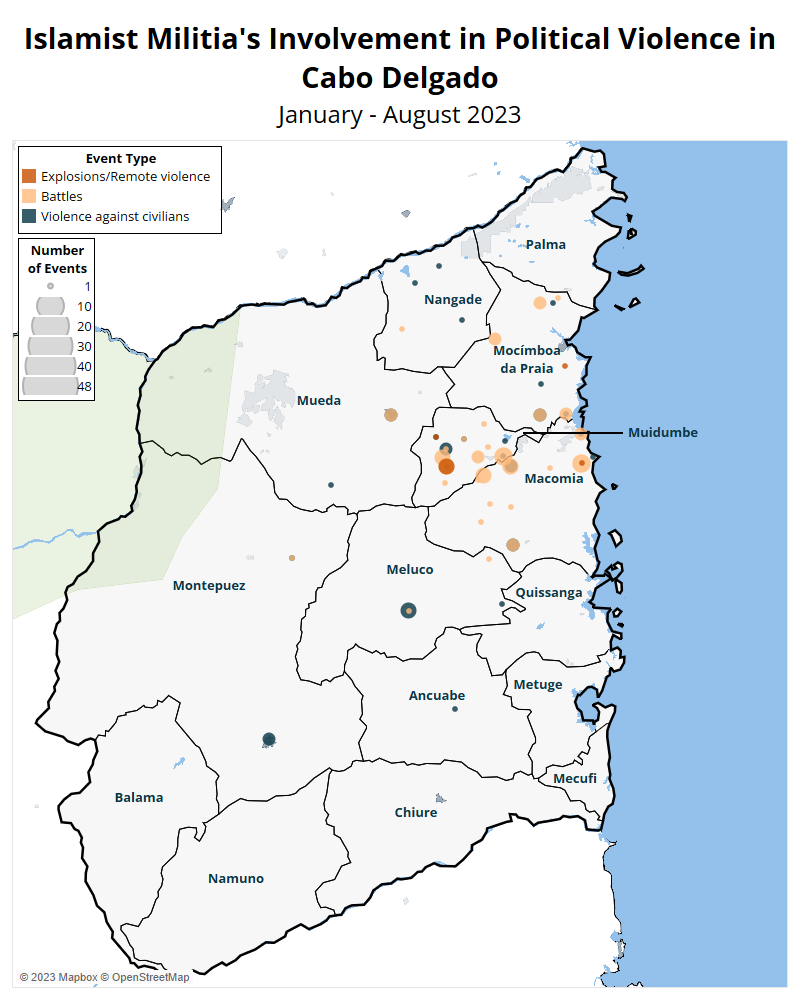

These tactical and organizational changes did not usher in a new era for ISM, but rather a steep decline in operations towards the end of 2022. In 2023, the group was estimated by some to have as few as 300 active fighters, compared to up to 2,500 in 2020.20UN, ‘Seventeenth report of the Secretary-General on the threat posed by ISIL (Da’esh) to international peace and security and the range of United Nations efforts in support of Member States in countering the threat,’ 31 July 2023 These active militants were reduced by mid-2023 to concentrated areas along the coast and in Catupa forest of Macomia district and neighboring areas in Mocímboa da Praia and Muidumbe districts. For the first eight months of 2023, ISM was involved in an average of just 11 political violence events per month, compared to an average of 36 per month in 2022.

The group’s leadership has also come under pressure, losing two of the most important leaders in 2023. Abu Yassir Hassan – a Tanzanian who, according to a March 2021 United States government report,21State Department, ‘State Department Terrorist Designations of ISIS Affiliates and Leaders in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Mozambique,’ 10 March 2021 led ISM – is thought to have been out of action since a car accident in early 2023. Bonomade Machude Omar, designated as ISM’s operational commander by the US in August 2021, was killed in action by Mozambican troops in August 2023.22State Department, ‘Designations of ISIS-Mozambique, JNIM, and al-Shabaab Leaders,’ 6 August 2021

Prospects Amid a Potential Security Vacuum

The geographic reach, number of militants, and operational tempo of ISM is currently in decline. The active presence of ISM is limited to a relatively small part of the province, though its capacity to conduct IED attacks in Macomia still hinders the movement of state forces.

However, ISM still has the capacity to resupply materiel through clashes with Mozambican Defense and Security Forces (FDS). For other supplies, including food, insurgents often trade with villagers in Macomia. The group still maintains support from transnational jihadist networks that include longstanding links with armed groups in DRC and valuable support networks in Tanzania. These support structures and tactics may enable the group to continue operating in Macomia for some time.

In security terms, its future will primarily depend on the effectiveness of state forces, both national and intervention forces. Though constrained, the upcoming withdrawal of SAMIM forces may present an opportunity for ISM. SAMIM is set to wind down in December 2023 before final withdrawal in July 2024.23Zitamar News ‘SADC starts the countdown on Cabo Delgado withdrawal,’ 12 July 2023 If ISM can sustain itself until this withdrawal, it may be able to take advantage of a security vacuum in Macomia, Meluco, Muidumbe, and Nangade districts. Mozambique’s FDS is still regularly and successfully targeted by ISM, despite ongoing support from the European Union and the US, and is unlikely to be able to fill the vacuum left by SAMIM. The RSF may, however, also expand its operations. The RSF has often been deployed in northern Macomia district, and maintains a joint base with the Defense Armed Forces of Mozambique in Ancuabe district in the south of the province. The Tanzania People’s Defence Force has also deployed in Nangade district, separate from SAMIM, and may also be positioned to deal with future outbreaks of violence.

Visuals in this report were produced by Ana Marco