Situation Update | November 2023

Sudan: RSF Expands Territorial Control as Ceasefire Talks Resume in Jeddah

3 November 2023

VITAL TRENDS

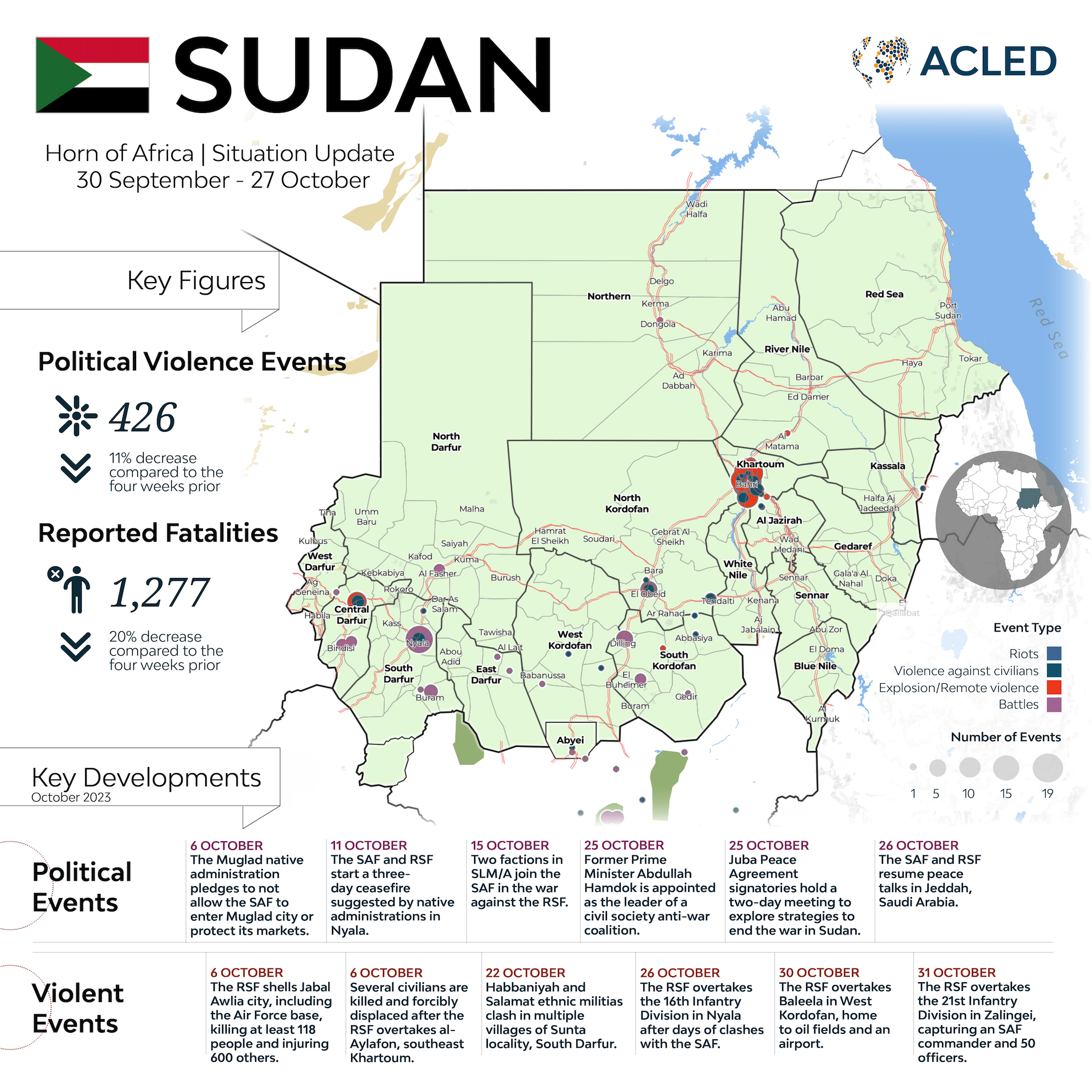

- Since fighting first broke out between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) on 15 April, ACLED has recorded over 2,800 political violence incidents and more than 10,400 fatalities1This number is a conservative estimate due to methodological limitations of real-time reporting in a conflict of this nature. For more, see the Fatalities FAQ in the ACLED Knowledge Base. in Sudan.

- From 30 September to 27 October, over 420 political violence incidents and over 1,270 fatalities were reported.

- Khartoum state had the highest number of political violence events and fatalities during the reporting period, with over 300 and 800, respectively. South Darfur state had the second-highest number of fatalities, at approximately 210, and nearly 30 political violence events.

- The most common event type was battles, with over 180 recorded, followed by explosions and remote violence events, at more than 190. However, compared to the previous four weeks, ACLED records a 17% decrease in battles and 14% decrease in explosions and remote violence.

RSF Expands Territorial Control as Ceasefire Talks Resume in Jeddah

15 October marked six months since the conflict between the SAF and the RSF first broke out in Sudan. The conflict has gradually expanded from the capital Khartoum to Sudan’s provinces, drawing in new actors as rebel groups and ethnic militias choose allies or pursue independent agendas. Peace talks between the SAF and the RSF have thus far failed to contain the fighting, with at least nine ceasefire agreements failing since April due to repeated violations.2Jack Jeffery, ‘Sudan’s army and rival paramilitary force resume peace talks in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia says,’ Associated Press, 26 October 2023 A new round of talks opened in the Saudi city of Jeddah on 26 October, in the latest attempt to facilitate the delivery of humanitarian aid and agree on a comprehensive ceasefire.3Nike Ching, ‘Sudan Cease-Fire Talks to Resume Thursday in Saudi Arabia,’ Voice of America, 25 October 2023 Meanwhile, civil society actors continue their attempts to organize a broad anti-war front, though conflict parties seem undeterred by these efforts.4Sudan Tribune, ‘President Kiir calls for unity among signatories of the Juba Peace Agreement,’ 26 October 2023; Radio Tamazuj, ‘Sudan: Anti-war civil forces form body led by former PM Hamdok,’ 27 October 2023

While preparations began for the peace talks in Jeddah, the RSF claimed to have taken over Sudan’s second-largest city of Nyala on 26 October. RSF also overran Baleela in West Kordofan and the 21st Infantry Division in Zalingei on 30 and 31 October, respectively. Meanwhile, various armed groups and militias not involved in the talks are launching their military offensives, each pursuing their independent agendas. This report examines how the war between the SAF and the RSF has evolved through October, become further entrenched in the capital Khartoum, and become increasingly intertwined with ethnic-based conflicts in the country’s peripheries.

The Battle for Khartoum

Since the beginning of the conflict, Khartoum has been the site of heavy fighting. In October, the RSF concentrated its war effort towards SAF bases within the Khartoum tri-city metropolitan area, while also expanding control over Sharg al-Nile, in southeastern Khartoum. The RSF currently controls large swathes within the tri-city area of Khartoum, Bahri, and Omdurman.

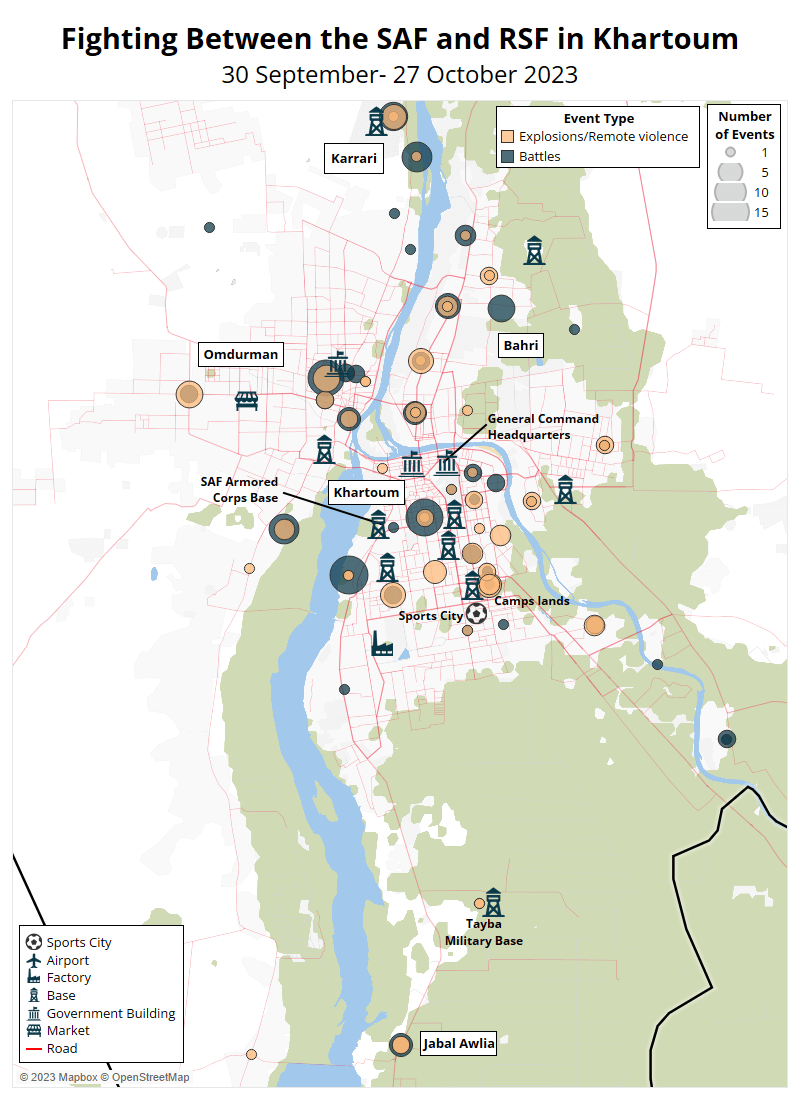

From 30 September to 27 October, ACLED records 129 battle events in Khartoum. Fighting broke out in several urban areas, including Jabal Awlia locality, the Armored Corps base, the General Command Headquarters (HQ), Camps lands, and Sports City (see map below). In particular, Jabal Awlia was the subject of heavy shelling by the RSF. It is a strategic location near the southern borders of Khartoum and White Nile state, home to the Air Force base, which the SAF took over in June. The White Nile River separates the RSF-controlled west side of Khartoum, and the east side, where the SAF Air Force base is located.

At the beginning of September, the SAF closed the main road in Jabal Awlia, which links North Kordofan and Khartoum through White Nile state. Jabal Awlia is strategically important for the RSF to encircle the state capital Kosti and attack the town from two sides – Umm Rawaba in North Kordofan and Jabal Awlia in Khartoum. To regain control of this route, RSF forces stationed in Tayba Military base began to encircle Jabal Awlia. On 6 and 7 October, the RSF shelled Jabal Awlia and the Air Force base, killing at least 118 civilians and injuring 600 others. This shelling, in turn, prevented SAF troops from breaking the siege on the Armored Corps and sending reinforcements.

Intense violence also continued around other SAF bases and RSF strongholds in the southeast areas of Khartoum. SAF airstrikes and artillery shelling on RSF positions in Sports City and Camps lands aimed to weaken the RSF’s defensive lines. For their part, RSF shelling of the Armored Corps SAF base resulted in the death of several SAF officers and soldiers, including Major General Ayub Mustafa.5Sudan Tribune, ‘Sudanese army general killed in RSF artillery attack,’ 15 October 2023. The RSF has not yet overrun the base, which could grant the RSF control over a vital Khartoum-Omdurman al-Fitahab bridge and likely inflict a significant blow to the SAF.

Elsewhere in the region, fighting persisted in Omdurman and Bahri areas, with reported exchanges of artillery fire and drone strikes having a devastating impact on civilians. In Omdurman, clashes largely concentrated around the Engineers Corps and the Karrari military area. After continuous fighting with the SAF between 5 and 6 October, the RSF gained control of al-Aylafon city in Sharg al-Nile. The city hosts the Pabcoo Company PS4 oil field station, a crucial facility for transferring South Sudanese oil to Port Sudan. The RSF’s takeover of the oil field led to its shutdown. As both warring factions vie for a decisive victory and control over Khartoum, clashes around strategically significant military bases are expected to remain intense.

South of Khartoum, the RSF controlled both sides of the River Blue Nile, particularly the localities of al-Kamlin and Sharg al-Jazira in al-Jazira state. On the western bank of the river, in al-Kamlin locality, the RSF presence grew after they took control of Jazira Agricultural Scheme Inspectorates in six villages. In overtaking these locations, the RSF disrupted a vital logistical route that the SAF relied on for mobilizing its troops and supplies to Khartoum State’s Sharg al-Nile locality, which was previously the route for deploying forces to the capital from Gedaref and al-Jazira states.6Sudan Tribune, ‘RSF extend presence to new areas in Sudan’s Al-Jazira State,’ 7 October 2023.

In White Nile state, tensions between the RSF and SAF run high after the RSF deployed its force across the al-Alaga area on the west side of White Nile state. The RSF withdrew from the area on 15 October after meeting with local leaders. In response to this RSF activity in al-Alaga area, the SAF deployed its forces across Ad Douiem on the east side of White Nile.

The RSF Captures Nyala and Advances in Darfur

South Darfur State

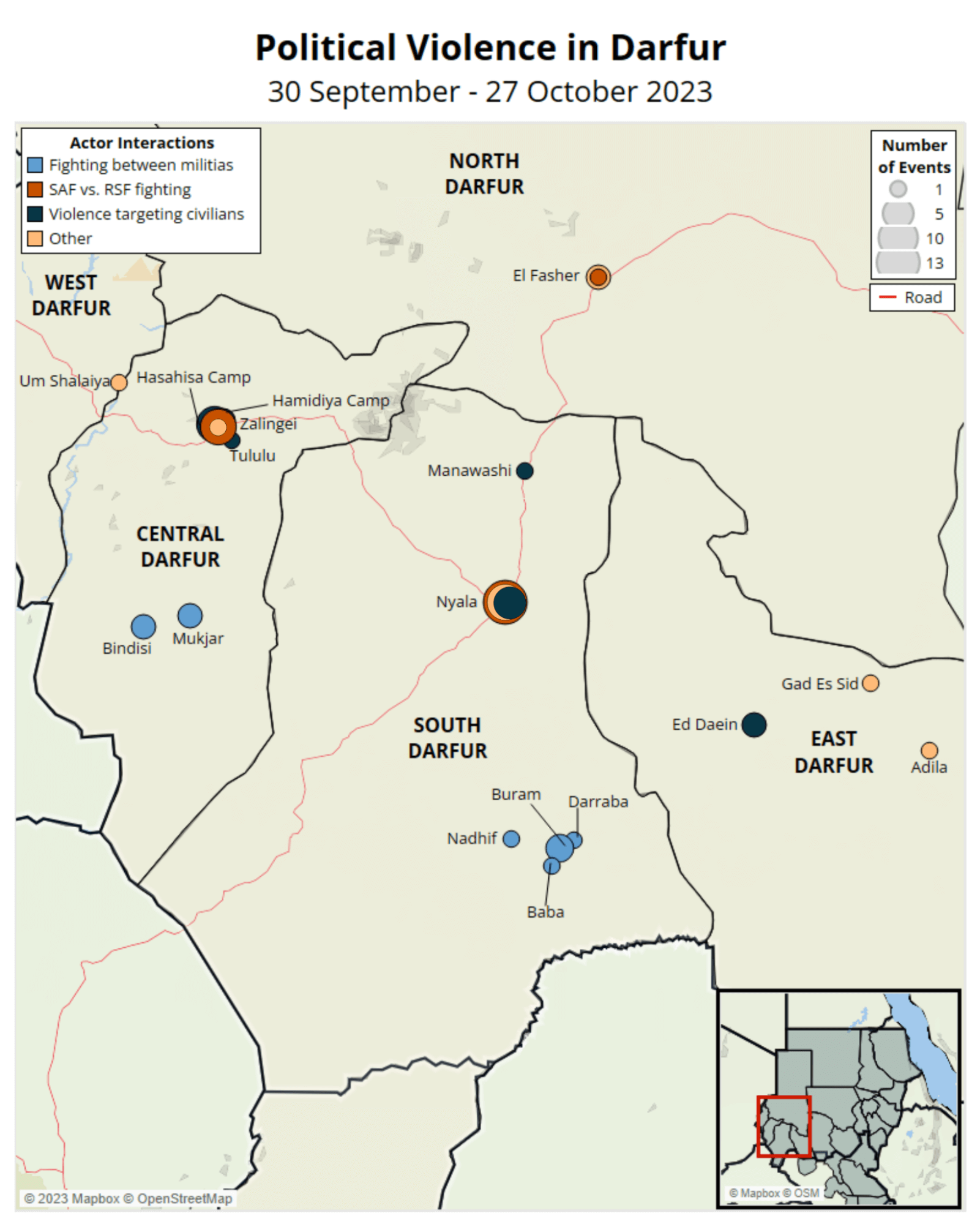

In South Darfur state, military confrontations flared up between the SAF and RSF, accompanied by drone strikes and airstrikes by both in the capital Nyala (see map below). Simultaneously, clashes involving ethnic militias associated with the RSF reignited in Buram locality in South Darfur.

In early October, the RSF significantly bolstered its presence in Nyala city by rallying fighters from Central, West, and East Darfur states with the intention of undermining the SAF 16th Infantry Division HQ. A temporary ceasefire, proposed by native administrations around 10 October, offered a brief respite. However, fighting resumed on 23 October as clashes concentrated in Congo and Khartoum Beliel neighborhoods. On 24 October, the RSF overtook multiple neighborhoods and the western section of the 16th Infantry Division HQ, but the following day, the SAF claimed it regained these captured territories.

On 26 October, however, RSF forces overran the SAF 16th Infantry Division base and seized control of Nyala city. The base was particularly significant for the SAF as it housed a pivotal component of its Western Region Command in Darfur. This Division included various battalions, such as artillery, engineers, and armored personnel. South Darfur state is strategically important due to its proximity near Chad, South Sudan, and Central Africa and its location for alleged RSF supply routes.7BBC, ‘Sudan conflict: RSF takes control of Nyala in Darfur,’ 26 October 2023.

Meanwhile, the RSF reportedly clashed with the Gathering of Sudan Liberation Forces – a faction of the Sudan Liberation Movement/Army (SLM/A) led by al-Tahir Hajar and one of the Joint Forces of Armed Struggle Movements8Sudan Tribune, ‘Minnawi warns against plans to attack Darfur joint force,’ 9 September 2023 – in the west of the SAF 16th Infantry Division. The Joint Forces include four of the signatories of the 2020 Juba Peace Agreement, and was established on 27 April 2023 to ensure the protection of civilians in Darfur.9The four groups are the Minnawi faction of the SLM/A, the Gathering of Sudan Liberation Forces, the SLM/A-Transitional Council faction, the Justice and Equality Movement led by Gibril Ibrahim, and the Sudanese Alliance Movement. See Sudan Tribune, ‘Minnawi warns against plans to attack Darfur joint force,’ 9 September 2023 Fighting with the RSF also broke out in El Geneina market in northwestern Nyala after the RSF attacked the group on 19 October, and continued through 24 October.

East Darfur State

In East Darfur, the RSF was involved in two main incidents. First, on 3 October, the RSF clashed with communal militias in Adila city. RSF forces traveled to this area from Khartoum after reports of dispute within the RSF ranks emerged. To avoid further escalation, the Maaliya native administration refused entry to additional RSF forces by suggesting that they store their equipment outside the city. This resulted in armed clashes between the RSF and communal militias in Adila.

The second incident was related to RSF forces capturing an SAF patrol vehicle in Ed Daein on October 18, which created tension in the city as the SAF wanted to retrieve the vehicle forcefully. The captured vehicle was peacefully returned on the same day, after the native administration – including representatives from the Rizeigat community – stepped in to de-escalate the tension by negotiating for the return of the vehicle. After this incident, the RSF announced that its forces took control of East Darfur while the SAF was still present in its base in the area.

Central Darfur State

Central Darfur was the site of a new round of violence. From 30 September to 27 October, political violence across the state increased by an estimated 56% compared to the previous four weeks. Armed clashes between the SAF and RSF forces were recorded in state capital, Zalingei city throughout October. On 31 October, the RSF claimed control of the city, including the SAF 21st Infantry Division command.10Radio Tamazuj, ‘RSF say they have seized army base in Zalingei, Central Darfur,’ 31 October 2023 Additionally, the RSF intensified its shelling on the Hamidia and Hisahias IDP camps, resulting in further displacement and dire humanitarian conditions for residents. It is unclear why the RSF attacked these camps.

Furthermore, the clashes between the Salamat and Beni Halba militias have not only persisted but have also expanded to encompass Mukjar and Bendasi in Central Darfur state. The two militias began to clash after a looting incident in May (for more, see Sudan Situation Update: October 2023). Previously, the clashes were mainly confined to South Darfur state, but in October, RSF members joined the fighting, aligning themselves along ethnic lines with either the Salamat or Beni Halba militias. RSF vice commander Abdulrahim Dagalo – the brother of RSF commander Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo ‘Hemedti’ – and Revolutionary Awakening Council commander Musa Hilal, who have influence in the region, attempted to mediate the two militias. However, their efforts ultimately proved unsuccessful, as Beni Halba refused the involvement of Dagalo.

Ethnic Fighting Erupts in Kordofan

In South Kordofan, the SAF clashed with Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-North (SPLM-N) al-Hilu faction. These clashes were primarily concentrated in the areas between Kadugli and Dilling, specifically in al-Takama, El Faragil, Karkaria villages, and extending to Damba village west of Kadugli. Meanwhile, the Hawazma-Baggara ethnic militia clashed with Nuba ethnic militia in Dilling city on 24 and 25 October, with the Nuba ethnic militia – which is backed by the SPLM-N al-Hilu faction. The Hawazma were recruited into the Popular Defense Forces in 2012 to support the SAF when the conflict between the SAF and the SPLM-N resumed.11Small Arms Survey, ‘Remote-control breakdown: Sudanese paramilitary forces and pro-government militias,’ April 2017

In response, the Dilling native administration intervened, securing the release of several captive ethnic militias to prevent further escalations. Additionally, a monitoring committee was formed to oversee the situation. These ethnic clashes add a layer of complexity to the already intricate situation in South Kordofan, where the SAF clashes with the RSF in the northern part of the state and the SPLM-N al-Hilu faction around Kadugli and other parts of the state on two separate fronts. The ethnic dynamics could further complicate the existing violence in the region, and unrest is likely to persist since the ceasefire talks do not include the SPLM-N al-Hilu faction.

Against the backdrop of the peace talks in Jeddah, and the RSF seizure of two Darfur state capitals, the dynamics of the conflict in Sudan are poised to undergo a significant transformation. The RSF’s potential goal of taking full control of the entire Darfur region looms, while the positioning of ethnic militias and armed groups in Darfur vis à vis the main conflict parties remains unclear. Each ethnic militia and armed group is driven by its own distinct objectives, posing further complexities that must be addressed both militarily and politically.