Actor Profile:

Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM)

13 November 2023

The third installment in our actor profile series mapping armed group activity around the Sahel is based on a joint report by ACLED and GI-TOC. Read the full report for more on JNIM’s operations and organizational structure, with a focus on the group’s engagement with illicit economies and tactical use of economic warfare.

All data are available for direct download. Definitions and methodology decisions are explained in the ACLED Codebook, and more information can be found in the ACLED Knowledge Base.

Al-Qaeda’s Sahelian Affiliate

Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (Support Group for Islam and Muslims, or JNIM) is a Salafi-jihadist group and the Sahelian branch of the transnational al-Qaeda organization. The armed group’s immediate parent organization is the Algeria-based al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), whose roots emanate from the Algerian civil war of the 1990s. JNIM’s genealogy dates back more than two decades to the founding of AQIM and its predecessor, the Salafist Group for Preaching and Combat (GSPC), and their implantation in the Sahara and Sahel.1Alexander Thurston, ‘Jihadists of North Africa and the Sahel: Local Politics and Rebel Groups,’ Cambridge University Press, 2020; Caleb Weiss, “Translation of a May 2006 Interview of Mokhtar Belmokhtar,” Line of Steel, 21 July 2020 Since then, the Sahelian insurgency has continued to evolve through splits, mergers, and group and alliance formations, with JNIM emerging from the March 2017 merger of Ansar Dine, AQIM’s Sahara region, al-Murabitun, and Katiba Macina. Each of these groups shares a common ideology and strategic objectives, but exhibits distinct profiles and characteristics in terms of composition, local interests, and operational focus, which to some extent continue to influence JNIM’s activity.

JNIM’s leadership system operates in a top-down hierarchy that includes three main tiers: central leadership, regional commanders, and local area commanders. Although its subgroups maintain distinct identities to an extent, JNIM has cultivated a strong collective identity associated with its overarching brand and affinity with al-Qaeda. Since its inception, JNIM has evolved from a loosely organized coalition of local jihadist militant groups to a strategically coherent entity. JNIM’s organizational evolution is the result of structural reforms that have enhanced coordination and deepened cooperation among its constituent groups. Organizational unity is further strengthened by internal oversight and overarching chains of command facilitated by the ongoing strategic deployment of senior military commanders to other JNIM subgroups and regions outside those cadres’ original areas of operation. It has also developed a strategic blueprint that includes a combination of guerrilla warfare, strategic use of violence, governance and population control, economic warfare, and media and propaganda operations.

JNIM has sought to portray itself as a ‘big tent’ alliance, striving to attract a wide range of local community and ethnic groups.2Héni Nsaibia and Clionadh Raleigh, ‘The Sahelian Matrix Of Political Violence,’ Hoover Institution, 21 September 2021 JNIM has historically drawn heavily from multiple ethnic constituencies, including Tuareg, Arab, Fulani, Songhai, and Bambara communities, largely reflecting the social fabric in the areas where it is active. However, through its growing influence and geographic expansion, it has also extended its appeal to include other ethnic groups such as the Dogon in ‘Dogon Country’ and Seno-Gondo plain, the Minyanka in Sikasso region, and Bissa, Djerma, Gourmantche, and Mossi in different parts of Burkina Faso and Niger. This inclusive approach has allowed JNIM to portray itself as a group that advocates for widespread communal support, enabling its expansion across ethnically and socio-politically diverse geographies of unparalleled reach in the region.

Beyond providing a detailed overview of JNIM’s structure, leadership, patterns of violence, and area of operation, the report gives particular focus on the underexplored dimension of economic warfare. This strategy has become an important aspect of JNIM’s overall strategy — a worrying development as JNIM holds its rank as one of the key armed actors in the Sahelian conflict ecosystem. Thus, JNIM is likely to continue deploying such tactics and assert its influence while undermining the state on the battle and governance front.

Activity and Areas of Operation

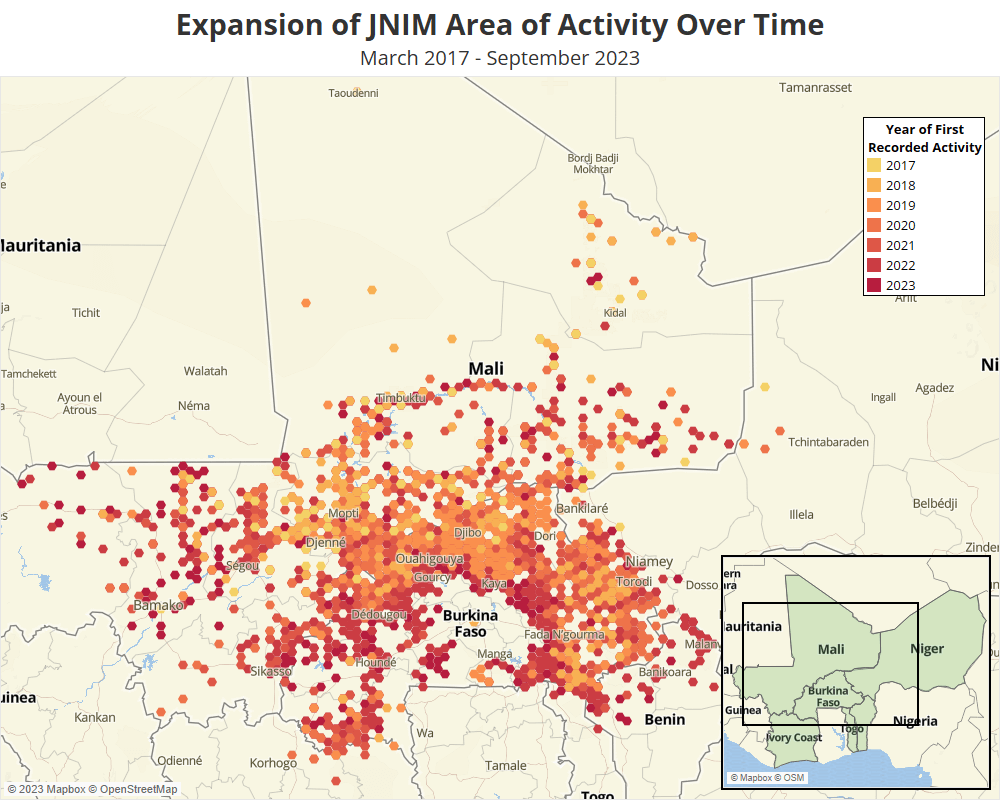

JNIM is the most active armed actor in the Sahel regional conflict. Its influence and reach extend across much of the central Sahel and into the West African littoral states, having expanded from the group’s traditional strongholds in northern and central Mali to the western and southern parts of Mali, most of Burkina Faso, parts of Niger, and the northernmost areas of Benin, Ghana, Ivory Coast, and Togo.

It began in central Mali with the emergence of Katiba Macina in early 2015, which has since become JNIM’s largest and most active subgroup, encompassing several of JNIM’s most active military regions. The birth of Ansarul Islam in Burkina Faso in late 2016 — subsequently incorporated into JNIM — facilitated the group’s continued expansion in Burkina Faso, which from the north of the country spread to southwestern Niger and eastern Burkina Faso between 2017 and 2018 (see map below). In the second half of 2018, JNIM further expanded its operations in southwestern Burkina Faso. The group then set its sights on Ivory Coast, where it launched its first offensives in mid-2020 before turning to Benin and Togo in late 2021. This multistage geographic expansion has seen JNIM’s power base and driving force gradually shift to central Mali and neighboring Burkina Faso.

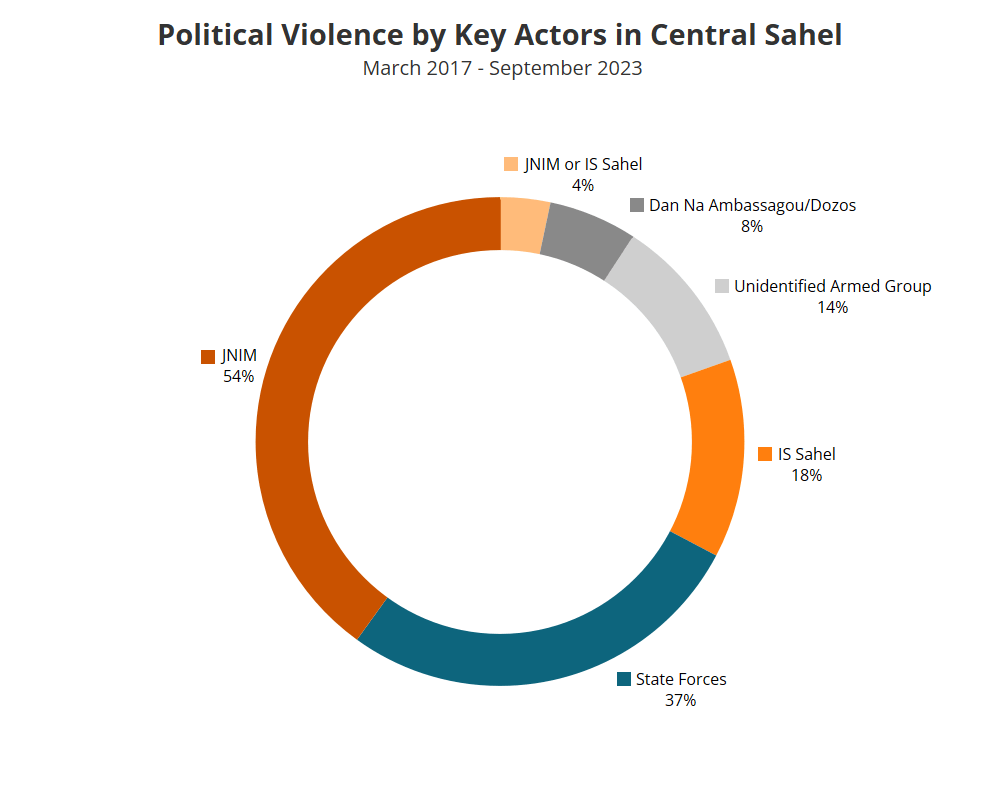

JNIM’s military efforts are focused on a wide range of adversaries, including international, regional, and local forces, as well as various non-state armed groups, including pro-government militias and rival jihadist militants such as the Islamic State Sahel Province (IS Sahel). Characteristic of JNIM’s warfare, the group’s activities have gradually increased in frequency, scope, and geographic reach as the group steadily expanded its military operations throughout the region. It maintains a high operational tempo that outpaces its adversaries and competitors, as evidenced by JNIM’s engagement in nearly as much violent activity as all other key actors combined (see graph below). JNIM is also distinguished by the fact that it has sustained a multi-front war in the central Sahel, regularly and simultaneously engaging in armed confrontations with the group’s various declared enemies.

JNIM has developed a diverse repertoire of violent tactics as part of its warfare efforts, employing targeted assassinations, kidnappings, complex attacks, and large-scale military campaigns. One of the hallmarks of JNIM’s violent tactics is the use of remote violence, including improvised explosive devices (IEDs), land mines, rockets, and mortar fire. Such events make up 16% of total JNIM activity, far higher than IS Sahel, for which such violence only makes up 3% of total activity. JNIM also frequently deploys explosives to destroy infrastructure, including military and security facilities, government buildings, schools, telecommunications antennas, electric lines and towers, and bridges. These tactics and capabilities have evolved and spread throughout the region as JNIM has expanded.

The group also deploys an array of nonviolent tactics to advance its objectives. These include various forms of resourcing and financing to sustain its activities like engaging in artisanal mining, livestock theft, fundraising, collection and extortion of zakat (or alms), looting and taxation of goods, and tapping into licit and illicit supply chains. JNIM also seeks to be a competing governance actor, control the population, and impose its vision of insurgent order. In areas under the group’s control or influence, it regulates social behavior by imposing dress codes, gender segregation, and other rules it considers in accordance with its interpretation of Islam.3Rida Lyammouri, ‘Centre Du Mali : Mobilisation Communautaire Armée Face À La Crise,’ 20 May 2022 While JNIM has relatively low bureaucratic capacity, it provides some basic services, notably justice and security provision and dispute resolution, and manages access for nongovernmental organizations.

Dynamics of a Regional Multi-Front War

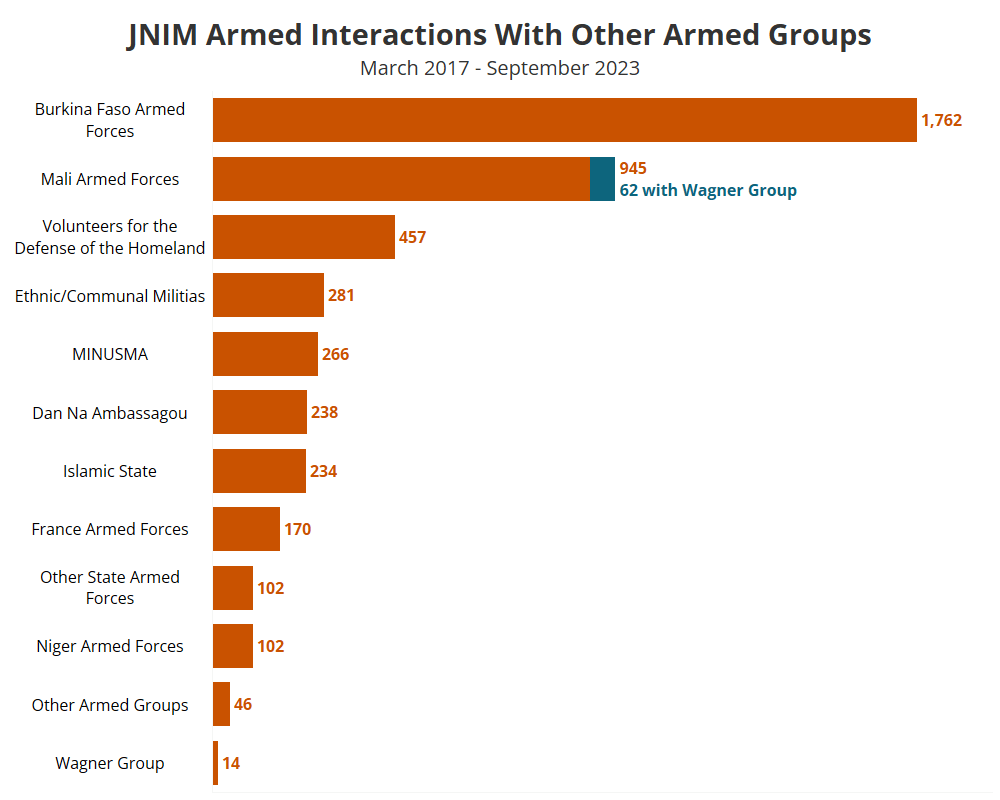

JNIM’s warfare focuses primarily on fighting international and local government forces in countries where the group is active (see graph below). It portrays itself as a vanguard against foreign invaders and an alternative to local governments, which it describes as corrupt, secular, and anti-Islamic ‘puppet regimes’ of the West.4Twitter, @MENASTREAM, 17 November 2017 For nearly a decade, French forces and the United Nations peacekeeping mission in Mali (MINUSMA) were the main enemies of JNIM, which the group’s media and propaganda frequently referred to as occupiers and invaders. Now that these missions are coming to an end — MINUSMA is scheduled to fully withdraw from Mali on 31 December 2023 — they have been replaced by mercenaries from the Wagner Group, which plays a similar role in JNIM propaganda.5Jeune Afrique, ‘ Mali : quand Wagner devient la cible privilégiée des jihadistes du JNIM, 10 November 2022; monitoring and review of JNIM media and propaganda materials.

Wagner has strengthened the Malian Armed Forces (FAMa) and contributed significantly to scaling up military operations and the return of FAMa to areas from which it had previously withdrawn. However, the overall impact of Wagner’s activities is arguably marginal, as JNIM has managed to maintain a high operational tempo in areas of central Mali where FAMa and Wagner have concentrated their joint efforts. JNIM has also steadily expanded its operations in the southern and western parts of the country, including around the capital Bamako. This is not to say that JNIM is unaffected by FAMa and Wagner operations, including attacks targeting civilians in areas of JNIM operation, which have demonstrated both JNIM’s inability to defend the communities it claims to protect and that it operates according to a logic of avoiding direct confrontation. JNIM has instead resorted to using IEDs and landmines, and has carried out suicide attacks against military bases and camps, including positions where helicopters and drones are stationed. The group has also stepped up its attacks against the pro-government Dan Na Ambassagou and Dozo (or Donso) militias, which are JNIM’s primary non-state rivals in Mopti and Segou regions, and communities associated with these militias in central Mali.

In neighboring Burkina Faso, JNIM is believed to control or exert significant influence over large swaths of territory, with activity in 11 of the country’s 13 regions. JNIM is the most active armed actor in conflict with government forces and the state-backed Volunteers for the Defense of the Homeland (VDP) militias. The violent interplay between JNIM (and also IS Sahel), government forces, and the VDP has driven a significant escalation of conflict in Burkina Faso, making it the most militancy-affected country in West Africa as of mid-2023. Burkina Faso’s location and difficulty dealing with the JNIM threat have also made it a staging ground for JNIM activities in neighboring Benin, Ivory Coast, Ghana, and Togo.

A major shift in JNIM’s violence is that the group initially engaged in selectively targeted military and security forces, communal leaders, and key collaborators of local and international forces. However, over time, JNIM has more frequently engaged in performative violence, as seen in successive suicide bombing campaigns in response to FAMa and Wagner operations. JNIM has also carried out increasing numbers of mass atrocities against communities it perceives as close to pro-government militias or IS Sahel. Mass violence by JNIM is especially pronounced in Burkina Faso, where the group justifies it as a response to the state’s counter-mobilization and widespread abuses and atrocities by government forces and the VDP against the Fulani community.

At the same time, JNIM was engaged in conflict with IS Sahel — an additional layer of violent dynamics in the continuously transformed Sahel conflict. Former allies JNIM and IS Sahel are engaged in a deadly conflict that escalated into a full-blown inter-jihadist war in early 2020. Each of these groups targets communities it perceives as a supporter of the other, resulting in severe consequences for the civilian population. The protracted conflict between the two groups has further exposed JNIM weaknesses, especially in areas where JNIM is relatively numerically inferior and does not exhibit the profile of a full-time fighting force, which IS Sahel has exploited strategically by prioritizing fighting JNIM rather than engaging in a broader multi-front war like JNIM. This has allowed IS Sahel to consolidate its control and influence in Mali’s Gao and Menaka regions, forcing JNIM’s northern regions of the Gourma, Gao, and Menaka to rely more heavily on their more battle-hardened fighters from central Mali and northern Burkina Faso.

In response to the IS Sahel threat, JNIM has mobilized fighters en masse in the Mali-Burkina Faso borderlands to conduct large-scale offensives in the Gourma region. However, IS Sahel has demonstrated strategic skill by choosing its battles carefully and often retreating tactically when faced with an overwhelming fighting force. As a result, the conflict between the two groups has reached a stalemate. Neither side is in a position to strike a decisive blow, although both have managed to temporarily expand their operations into areas under the other’s influence.

State Disruption and Population Control Through Economic Warfare

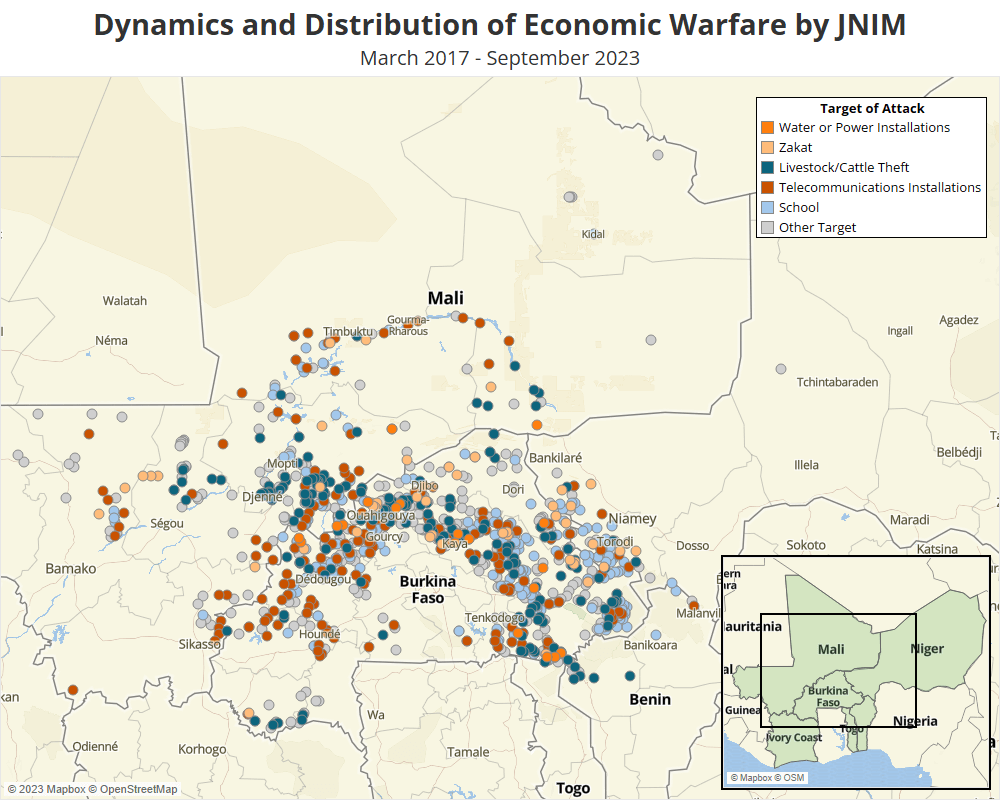

Aside from direct confrontation, economic warfare also serves as a key component of JNIM’s strategy to undermine its adversaries’ stability, weaken their resolve, and create opportunities for its expansion. JNIM employs economic warfare tactics across all the countries in which it operates (see map below). However, the intensity and spread of such activities have been notably pronounced in Burkina Faso.

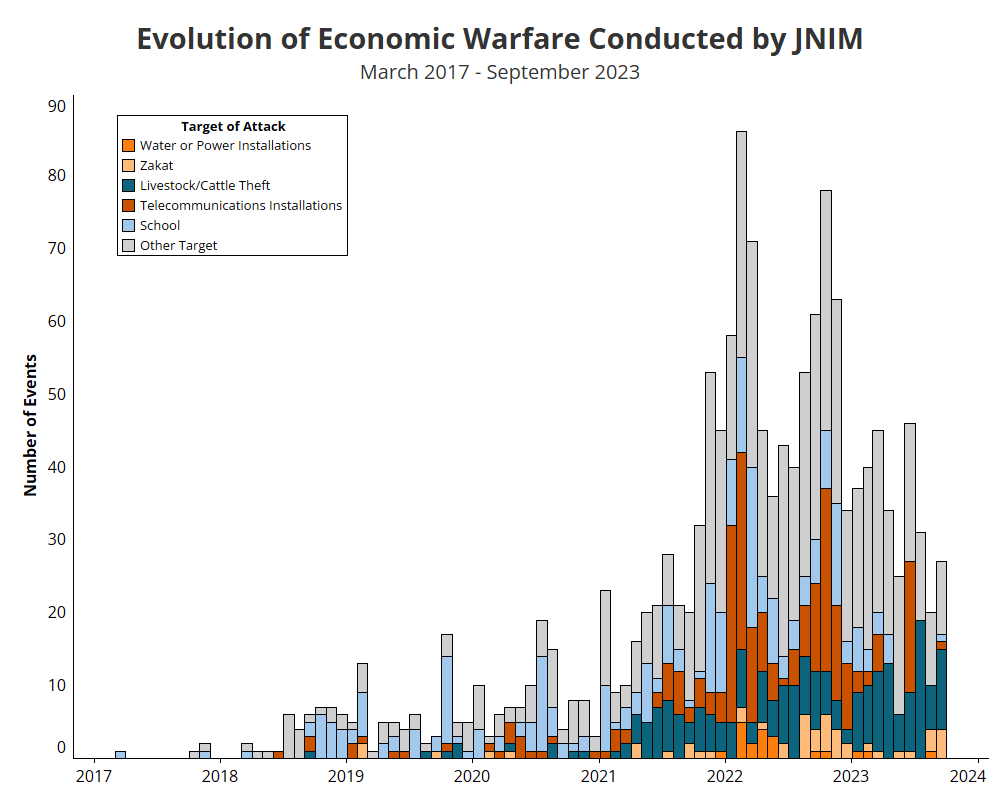

In the initial phase of asserting control, JNIM follows a blueprint that aims to eliminate symbols of state presence and undermine the government’s authority. Key targets in this phase are police and gendarmerie stations, military bases and camps, mayor’s offices, prefectures, and other state institutions, which are targeted to create a power vacuum and pave the way for JNIM to establish its own proto-governance structures and control the populations. JNIM’s economic warfare activities have gradually increased but also diversified following JNIM’s expansion across the region (see graph below).

Aside from these direct strikes on emblematic representations of state power, JNIM strikes on other infrastructure also serve a variety of specific goals. By targeting educational institutions, JNIM further eradicates symbols of state presence and disrupts the state’s ability to provide a basic public service. Attacking schools also allows JNIM to impose its own ideological framework on the population, as it seeks to replace secular education with religious instruction based on its interpretation of Islam.

By targeting roads, bridges, markets, transportation, and other essential infrastructure, the group simultaneously undermines the financial capacities of states and the logistical capabilities of government forces, and disrupts local economies to manipulate them for its own gain. Such strikes have included large-scale attacks on commercial, supply, and logistics convoys escorted by military forces on major transit routes, primarily in Burkina Faso, but also in Mali. JNIM also frequently sets up irregular checkpoints, where fighters gather intelligence and conduct identity checks in search of military and security force members, state militiamen, and collaborators. When running checkpoints they frequently seize opportunities to extract resources for their sustenance by looting vehicles, motorcycles, and other goods.

JNIM also imposes embargoes and blockades on towns and villages — or whole administrative subdivisions such as the Bandiagara region (‘Dogon Country’) in Mali, and in the Kompienga Province of Burkina Faso’s Est region6Le Figaro, ‘Burkina : des civils tués dans l’Est, leur nombre encore incertain,’ 26 May 2022 — perceived as non-compliant or aligned with the state or pro-government militias. Now a JNIM hallmark, this tactic has been employed in various towns and villages in both Mali and Burkina Faso, and to a lesser degree in Niger. The group has imposed large-scale embargoes — including the sabotage and destruction of water installations and powerlines — on vital agricultural areas, such as the Niono area in Mali and the Sourou Valley in Burkina Faso.

Beyond causing immense hardship for affected populations, the imposition of embargoes or blockades fragilizes relations between the population and authorities due to the latter’s inability to provide basic services with the potential of sparking civil unrest. Targeting telecommunications installations, including antennas and base stations, enables the group to control information flow. By disrupting communication infrastructure, JNIM not only deprives local populations and businesses of essential services but also gains an advantage in shaping the narrative around its activities and objectives at the local level, often in combination with psychological operations involving preaching and sermons. It further disrupts the coordination and communication capabilities among the military, security forces, and local authorities, making it more difficult for them to alert in the case of attacks and effectively coordinate counter-insurgency operations against JNIM.

JNIM’s Role in the Sahel’s Unfolding Crisis

The role of JNIM in the ongoing Sahel conflict cannot be understated, as it remains the most active armed actor, with activities spanning eight countries. The prevailing geopolitical turmoil amid successive coups in the central Sahel provides ample opportunity for the group to continue its advance and push its agenda in the absence of a more holistic approach and international cooperation to combat the regional insurgency. Clearly, the group has developed and adopted a comprehensive strategy to undermine state presence and assert its influence in its areas of operation.

However, the escalation and prolongation of the conflict continue to present challenges to JNIM. IS Sahel continues to inflict heavy blows on JNIM despite mass mobilization by JNIM. Meanwhile, throughout August and September 2023, no hostilities have been observed between the jihadist rivals, with reports indicating a truce in place and conciliation efforts. At the same time, counter-mobilization and the shifting strategies of states fighting JNIM have also made the war increasingly costly for the group as it takes more frequent blows. This includes the ongoing air war against the group, with government forces significantly leveraging aerial assets, in particular Turkish Bayraktar TB2 drones. In Burkina Faso, the group faces increased joint operations by government forces and the state-backed VDP militia, whose sphere of influence continues to expand despite high casualty rates on all sides in the conflict, which has reached civil war-like proportions. In Niger, JNIM’s activities remain secondary and are limited to the southwestern parts of Tillaberi, with IS Sahel being the dominant actor in Tillaberi and adjacent regions. In Mali, FAMa and Wagner operations are edging closer to JNIM’s historic strongholds in the Tombouctou and Kidal regions, setting the stage for a new phase of the conflict. In August 2023, FAMa and Wagner took control of the MINUSMA camp and town of Ber following three days of intense combat with JNIM and the ex-rebel bloc, Coordination of Azawad Movements (CMA).

In response to the FAMa and Wagner offensives, CMA — as part of a coalition of predominantly Tuareg and Arab armed groups known as the Permanent Strategic Framework (CSP) — and JNIM have simultaneously launched preemptive offensives to move the battle further south through a series of attacks in the Gao, Mopti, and Tombouctou regions. These offensives are still in the early stages, but have resulted in several military camps being overrun and FAMa suffering heavy human and material losses. If this trend continues, it could lead to even greater challenges for FAMa and Wagner to regain momentum and pave the way for JNIM to further consolidate its position in the central Sahel, particularly in Mali. The security vacuum could allow JNIM to expand its influence deeper into the southern regions and beyond its traditional strongholds. This expansion could lead to a more pronounced hybrid governance model, or parastate(s), in which JNIM coexists and sometimes collaborates with other non-state actors such as CSP and IS Sahel. This could lead to a mosaic of territories under varied control and have detrimental consequences for the Malian state, which is already highly fragmented.7Dr. Virginie Baudais, ‘Mali: Fragmented territorial sovereignty and contested political space,’ Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, 16 June 2020 Given the ongoing geopolitical instability and the lack of a unified international response, this scenario could further challenge state sovereignty in neighboring Burkina Faso and Niger and complicate international intervention efforts.

Another possible trajectory considers the challenges facing JNIM. The risk of a resumption of hostilities with IS Sahel is high given the fighting between the two groups over the past four years. This, along with increased counter-mobilization efforts by state actors, could strain JNIM’s internal cohesion. It could become difficult for the group to maintain a unified front, leading to fragmentation, which could provide opportunities for IS Sahel to attract dissenting fighters, as was the trend between 2017 and 2019 in Mali and Burkina Faso. Decentralized factions could emerge, operating independently and possibly pursuing different strategies and goals. While this could weaken the overall strategic position of the JNIM, it would also make the conflict more unpredictable and further complicate the conflict landscape in the Sahel. If JNIM’s opponents continue to target civilians in the group’s areas of influence and contested territories, the group could lose further legitimacy in the eyes of the population it claims to protect. Increased attacks on civilians by JNIM itself and collective punitive measures such as embargoes and blockades could contribute to further limiting the JNIM’s ability to implement its governing agenda, leading to difficulties in maintaining influence and control over the population.

Given the protracted nature of the conflict and the human and economic costs, it is deeply troubling that a reset of the crisis is emerging after more than a decade of sustained violence. Despite similarities with the onset of the crisis in 2012, an entirely different and new security context is developing in the central Sahel, characterized by a steadily deteriorating security situation and political instability in which the international community has limited ability to make a difference. Regardless of how the conflict evolves, JNIM will continue to play a central role as the predominant armed actor.

Visuals in this report were produced by Christian Jaffe