Q&A with

Luca Nevola

ACLED Middle East Regional Specialist

Attacks by Yemen’s dominant Houthi forces on international shipping passing through the Red Sea have multiplied in number and severity since the October outbreak of war in Gaza, worrying many that they could provoke a regional escalation. But in this Q&A, Middle East Regional Specialist Luca Nevola argues that despite their rhetoric, the Houthis will likely avoid further overspill. The Houthis are calculating their moves to distract Yemenis from domestic frustrations and capitalize on growing anti-Israel sentiment in the Middle East.

What’s the scale of the upsurge since October of attacks by Yemen’s Houthi forces on shipping in the Red Sea?

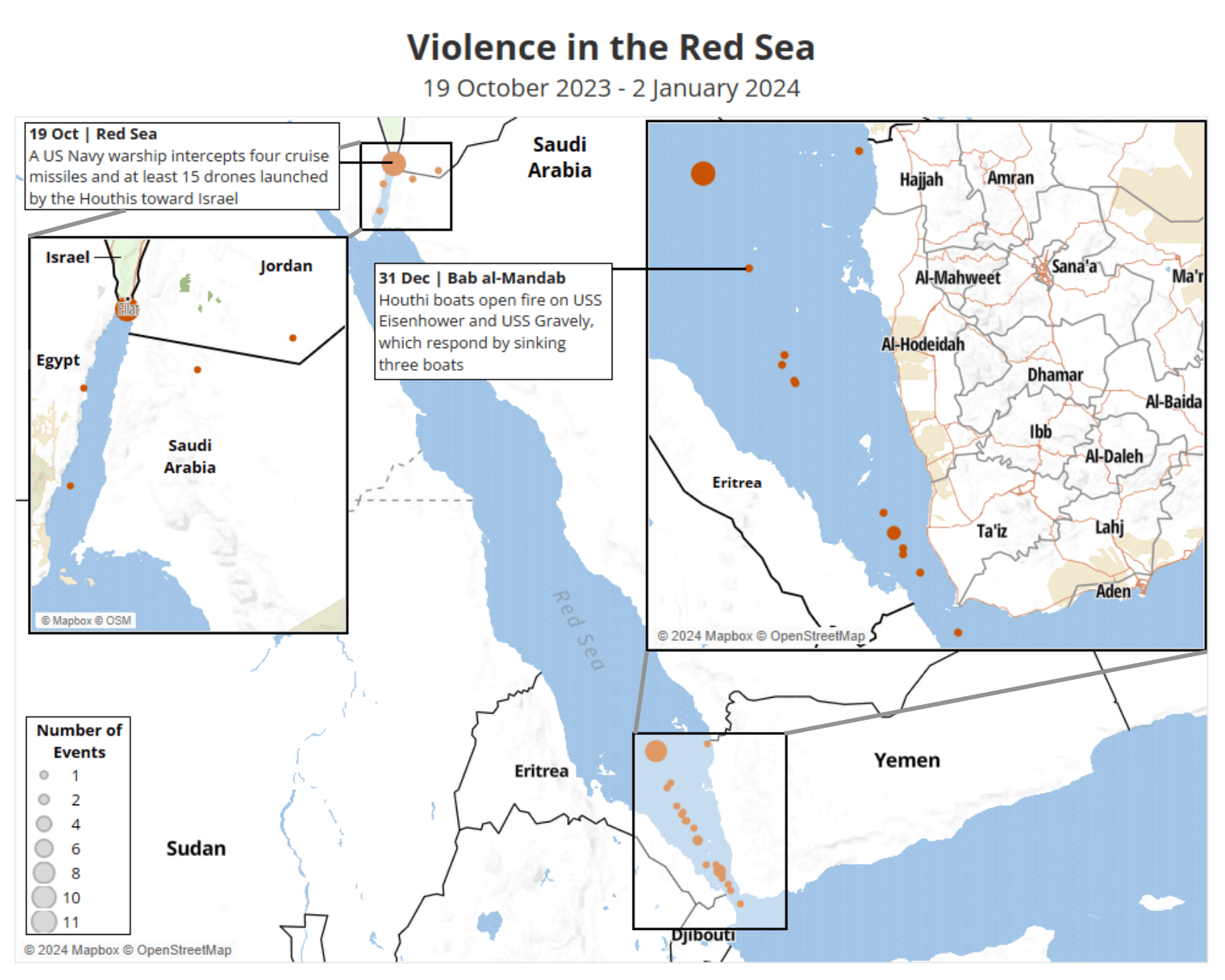

Since 19 October, we have recorded around 50 violent events in the Red Sea, mostly attacks involving Houthi forces and international vessels. It’s a big escalation, almost one-fifth of around 250 events ACLED has recorded in the Red Sea since 2015.

This is actually the Houthis’ fourth wave of attacks in the waterway, which is the conduit for at least one-tenth of world seaborne trade. In the first, between 2015 and 2016, the Houthis relied on shelling from the shoreline after they won control of the western Red Sea coast and captured the old Yemeni army stockpile of anti-ship missiles. From 2017 onward, the Houthis began relying more on water-borne improvised explosive devices, known as WBIEDs. Then in 2020, and peaking in 2021, the Houthis expanded the use of WBIED attacks, followed by a truce in 2022.

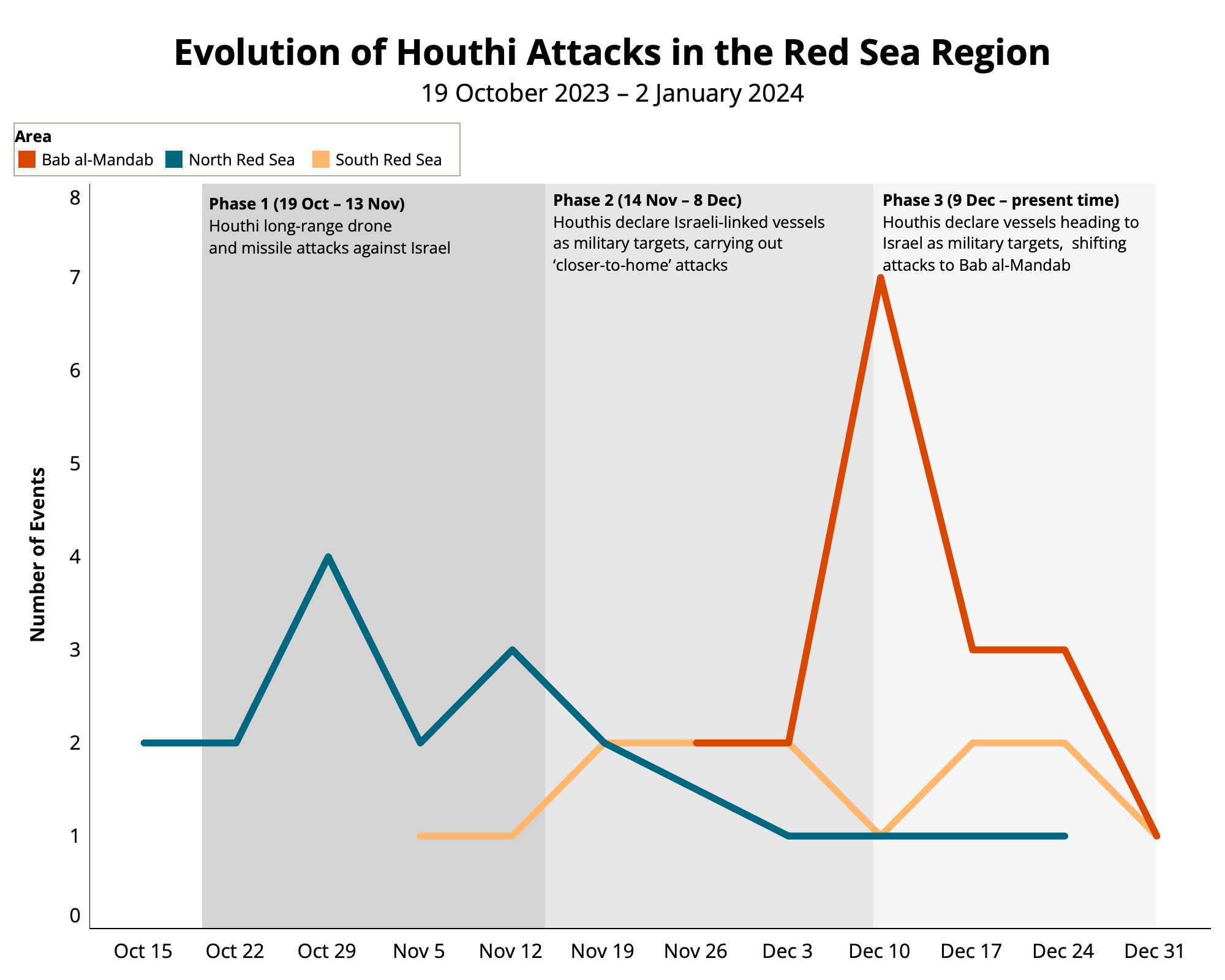

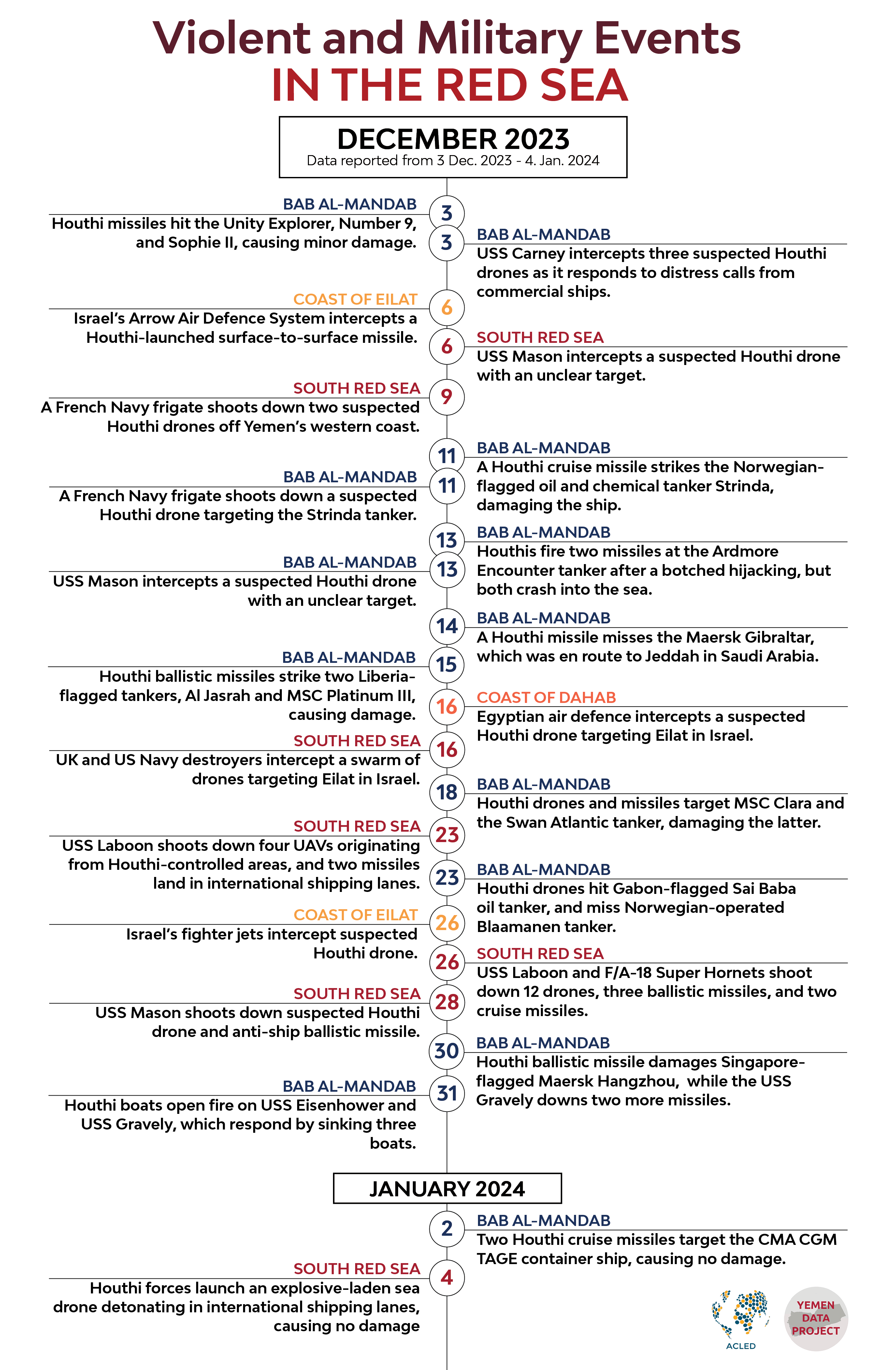

The upsurge since October has broken the lull in three escalatory steps. First was a group of relatively ineffective, long-range drone and missile attacks, mostly intercepted by the United States or Israel. Then, after mid-November, when the Houthis claimed they would start targeting Israel-linked ships, the attacks moved closer to Yemen and the southern Red Sea region. A third phase began after 9 December, when the Houthis said they would target all vessels directed at Israeli ports. After that, we saw the highest rate of attacks, mostly concentrated around the Bab al-Mandab region.

It’s not just the frequency of events that makes this recent escalation unprecedented — or that one of Israel’s missile interceptions took place outside the Earth’s atmosphere, the first recorded combat in outer space — but also the fact that they now include commercial ship hijackings and the first use of long-range ballistic and cruise missiles fired toward the distant southern port of Eilat in Israel. Another new element is that the Houthis now have their own anti-ship missiles and drone technology to conduct these maritime attacks.

What do you think happens next?

It may surprise you to hear that I believe the risk of regional escalation is low, at least from the Houthi side. The chances that a Houthi missile or drone will actually strike a city or civilians in Israel are extremely low. Even Eilat, in the far south of Israel, is 1,600 kilometers (1,000 miles) from Yemen and at the limit of the Houthis’ missile range. From a military standpoint, the missile and drone launches against Israel were symbolic messages. Attacks against international shipping lanes pose a different level of hazard. Pushing the envelope too much could trigger an international reaction.

From a US perspective, the Houthis crossed a red line by increasing the number of attacks against commercial ships. Very often, though, the Houthis escalate military activity right before talks or right before agreements in order to show that after the agreement, they are de-escalating. I really don’t think that the Houthis are willing to trigger a regional escalation or a direct intervention of the US. They hope they have established a balance of controlled deterrence and that the likelihood of further US or other retaliation is small. And if the US wants to react, it’s more likely it will conduct covert operations to selectively target infrastructure in Yemen. Overall, the balance between different positions is precarious, and a miscalculation could trigger an escalatory loop. But I’d argue that we’ll see a decrease in the number of attacks against commercial ships in the Red Sea in the coming weeks.

Why do you think the Houthis decided to escalate?

The Houthis’ stated desire was to counter the crushing Israeli attacks on Palestinians that followed the Palestinian group Hamas’s own brutal assault on areas around Gaza on 7 October 2023. It’s worth noting that the first Houthi drone and missile attacks in the Red Sea occurred on 19 October, just two days after an explosion killed many Palestinians in Gaza’s al-Ahli hospital — different sources give tolls of between 100 and 500 dead, and the origin of the blast is contested — a burning issue that at the time many assumed was caused by an Israeli strike. Abdulmalik al-Houthi, the Houthis’ self-proclaimed leader, even said he would intervene directly in the Gaza conflict with drones and missiles if the US got directly involved.

But we also need to consider developments inside Yemen since April 2022, when the UN-mediated a truce in the civil war in progress since 2015. Following the cease-fire, the Houthis, who preside over 80% of the Yemeni population, launched a process of institution-building and state reform. The group had only ever run a war economy since taking power in 2014-15, and their leader, Abdulmalik al-Houthi, delivered 12 formal lectures as a sort of religious manifesto for change. Even after the truce was not renewed in October 2022, he and the President of the Supreme Political Council, Mahdi al-Mashat, doubled down on their commitment to improve state services and launched a development program aimed at economic self-sufficiency. In September 2023, Abdulmalik al-Houthi announced that the Sanaa-based government might be dismissed. There were rumors that he wanted to replace ministers with technocrats or at least more moderate characters. It seemed the Houthis were trying to normalize their political elite to prepare for a peace deal with Saudi Arabia.

But the Houthis were not very successful. In the weeks and months before the eruption of the Gaza conflict, unrest had started building up in Houthi-controlled areas demanding payment of salaries and venting public discontent at poor governance. Teachers went on strike. Hundreds of thousands of Yemenis took to the streets to celebrate Yemen’s 26 September 1962 ‘revolution day,’ sacred to the regime that preceded the Houthis. The Houthis repressed the demonstrations and arrested hundreds of people.

So it’s quite possible that another reason for the Houthis’ Red Sea escalation was to distract Yemenis’ frustration with their own government.

There are doubtless other causes, too. At a time of bilateral talks with Saudi Arabia, the Houthis could have seen a maritime escalation as a way to gain leverage against Riyadh. Another is rooted in ideology: stands against Israel and US interventionism in the Middle East lie at the heart of Houthi ideology. Lastly, that ideology is linked to political affiliation: the Houthis are self-proclaimed members of the ‘axis of resistance,’ which also includes Syria, Lebanon’s Hezbollah, militias in Iraq, and of course its most powerful member, Iran.

Where do the Houthis fit into the axis of resistance? Are they allies or, as many in the US allege, the puppets of Iran?

For sure, there was some sort of coordination with the other members of the axis of resistance. In a speech early in the crisis, Hassan Nasrallah, the leader of Lebanon’s Hezbollah, said the axis would respond to the Israeli aggression through groups in Iraq and Yemen. Yemen is a perfect launch pad for attacks against Israel, because the risk of regional escalation is much lower than it would be if the strikes came, for example, from Lebanon. Yemen provided plausible deniability to Iran, Hezbollah, and the other members of the axis of resistance.

But the longer-term relationship between the Houthis, the US, and Iran has been a sort of self-fulfilling prophecy. When the conflict erupted back in 2015, despite Saudi allegations to the contrary, the degree of Iranian support was extremely low. There were, however, some political and ideological connections. These increased with transfers of technology and expertise that allowed the Houthis to produce locally manufactured missiles and drones and to improve their strategic military skills. By 2023, the scale of the escalation was made possible by some transfers of components, new technologies, and by the presence of Iranian experts supporting the Houthis.

At the same time, the political relationship between the Houthis and Iran developed and the Houthis started publicly acknowledging their allegiance to Iran’s axis of resistance. The current situation is a balancing act. Abdulmalik al-Houthi may have some senior advisors affiliated with the Iranian Revolutionary Guards and Lebanon’s Hezbollah. Nonetheless, the Houthi leadership has decision-making power within Yemen. The Houthis are also aware of how Iran needs them not just as a proxy but as a testing ground for missiles, drones, and military strategies. Abdulmalik al-Houthi may be connected to Iran but he is an autonomous actor who wants to be considered at the same level as other axis of resistance partners, including Iran.

With axis of resistance leaderships in Iran, Syria, Lebanon, and Yemen sharing a heritage outside the Sunni Muslim mainstream, is there a religious basis for the alliance?

No, I don’t think they are allies because of religion. From time to time, yes, the Houthis describe themselves as members of the broader Shiite Muslim milieu. But the Houthis are Zaydis and the Iranians are Twelvers. I sometimes hear scholars claiming that the Houthis are becoming Twelvers, but that’s not correct. Perhaps it’s true that Houthi ideology is moving in a different direction from the traditional Zaydi beliefs, but the Houthis hold firmly onto their Zaydi faith, and there are major doctrinal differences between the Zaydi and Twelver sects.

Whatever the motivations and alliances, isn’t it very dangerous to attack a major global shipping lane like the Red Sea?

Yes. But it’s been an emerging situation, not a strategy. When they presented themselves as champions of the resistance against Israel, the Houthis began to realize that they could capitalize on a lot of domestic and regional anger with Israel. Being able to hold Israel, the US, and the world hostage by threatening maritime transportation is a point of tremendous strength and pride. And the Houthis calculate that the US and Israel don’t actually have many ways to retaliate against them. The only effective measures against the Houthis would be extremely severe, like for instance, the US designation of the Houthis as a foreign terrorist organization or launching direct strikes against Houthi infrastructure in Yemen. And this could trigger regional escalation.

The Houthi calculus is fairly realistic. The US does not want to disrupt Houthi-Saudi negotiations to end the civil war in Yemen. Saudi Arabia also wants to strengthen, not disrupt peace talks. Many US regional partners, including Gulf countries, are against a direct intervention of the US in Yemen, partly because their populations are overwhelmingly pro-Palestine. The only nearby country that is pushing for more decisive measures against the Houthis is the United Arab Emirates. Most regional states, however, would find it hard to justify supporting an attack on the Houthis at a time their actions are extremely popular across the Middle East.

The Houthis also currently have the upper hand in military terms within Yemen. If the civil war resumes, they would probably be in a position to gain some key areas like the oil-rich Marib or Shabwa governorates. The only way to push them back would be for Saudi Arabia to intervene directly with airstrikes, which Saudi Arabia does not want to do at present.

It’s true that a US attack on 31 December killed 10 Houthis and sank three of their boats that had attacked a commercial ship. With US forces claiming that US helicopters responded to Houthi fire, that is possibly the first direct battle between the two sides, if we don’t count previous Houthi downings of US drones and US strikes on Houthi radars in 2016. But these casualties are unlikely to persuade the Houthis to change course. They believe they are gaining reputation and face a low risk of major retaliation from the US or from Saudi Arabia.

How are Houthi media channels treating all this?

There is a certain level of triumphalism, of course. The Houthis are trying to promote an image of the noble Yemeni people acting in support of the Palestinian resistance. They claim that Yemen is the only country supporting Palestine, whether through popular mobilization, the massive pro-Palestine demonstrations of recent months, media support, and also military actions. They also compare their position with other Arab countries like Saudi Arabia and the UAE, which they portray as sitting and doing nothing.

I should add that in public, the Houthis claim that international shipping lanes are actually safe because they are only targeting vessels directed at Israeli ports or linked with Israel. They blame the US for using this escalation as a pretext not to protect the freedom of navigation to militarize the Red Sea and to protect Israel. In truth, the 31 December attack that triggered US response was against a Danish-owned vessel. On 2 January, they attacked a ship that was actually headed towards Egypt. This plain misrepresentation shows how much we are in an age of post-truth: the Houthis’ domestic audience will believe them; the regional audience will believe them; and they’re achieving what they want, blaming the US for the escalation.

But outside countries won’t believe that. In December, it seemed like the international community was, for the first time, on the verge of recognizing the Houthis as part of the governance of Yemen. Have they sacrificed that?

This escalation will have long-lasting effects on how the international community perceives the Houthis. It will be harder for them, at least in the near future, to promote the idea that they could be a moderate force ruling over Yemen. Already, because the Houthis are perceived to be too close to Iran, there is a strengthening movement in the US, including prominent scholars of Yemen, that supports the full recognition and arming of the old Internationally Recognized Government still hanging on in south Yemen. The UAE is also demanding the US to re-designate the Houthis as a foreign terrorist organization and that it militarily intervene.

So, even if the Houthis feel empowered in their short-term calculus, are they taking a long-term gamble after all?

Yes. Some Houthi leaders are acting from ideological motives. The Houthis do not just uphold an anti-imperialist view, oppose US interventionism in the Middle East, and reject political Zionism; they are also self-declared antisemites. The main Houthi motto, painted on many walls in the capital, Sanaa, says: “Death to America, Death to Israel, and a curse on the Jews.” They think that the Jews, as a race and as lineage, are somehow responsible for conspiracies damaging the Islamic nation across the board. They think that there is a Jewish lobby in the US that is ruling over the world and pushing the US government to intervene in the Middle East. Hence the pro-Palestine stance.

A few months ago, for instance, I conducted a study where I tracked Houthi discourse on Twitter [now known as X]. The main topic shared by all the Houthi leaders was a positive view on Palestine and a negative view about Israel. On a personal level, Houthi leaders truly believe what they say.

Among the general public, too, demonstrations are a very good way to measure popular consensus. In October, ACLED recorded around 550 pro-Palestine and anti-Israel demonstrations in Yemen. This is more than the country’s combined prior eight years of demonstrations focused on Palestine. We also recorded a lot of pro-Palestine demonstrations outside of Houthi-controlled areas. In fact, Yemeni political actors opposed to the Houthis are now complaining that they shouldn’t be leaving the Houthis free to capture all the popular support on this issue.

Luca Nevola was speaking to ACLED Chief of External Affairs Hugh Pope.

Recent ACLED publications on Yemen:

Middle East Regional Overviews

Beyond Riyadh: Houthi Cross-Border Aerial Warfare 2015-2022 (17 January 2023)

Violence in Yemen During the UN-Mediated Truce: April-October 2022 (14 October 2022)

The Myth of Stability: Infighting and Repression in Houthi-Controlled Territories (9 February 2021)