Situation Update | February 2024

Sudan: The SAF Breaks the Siege

16 February 2024

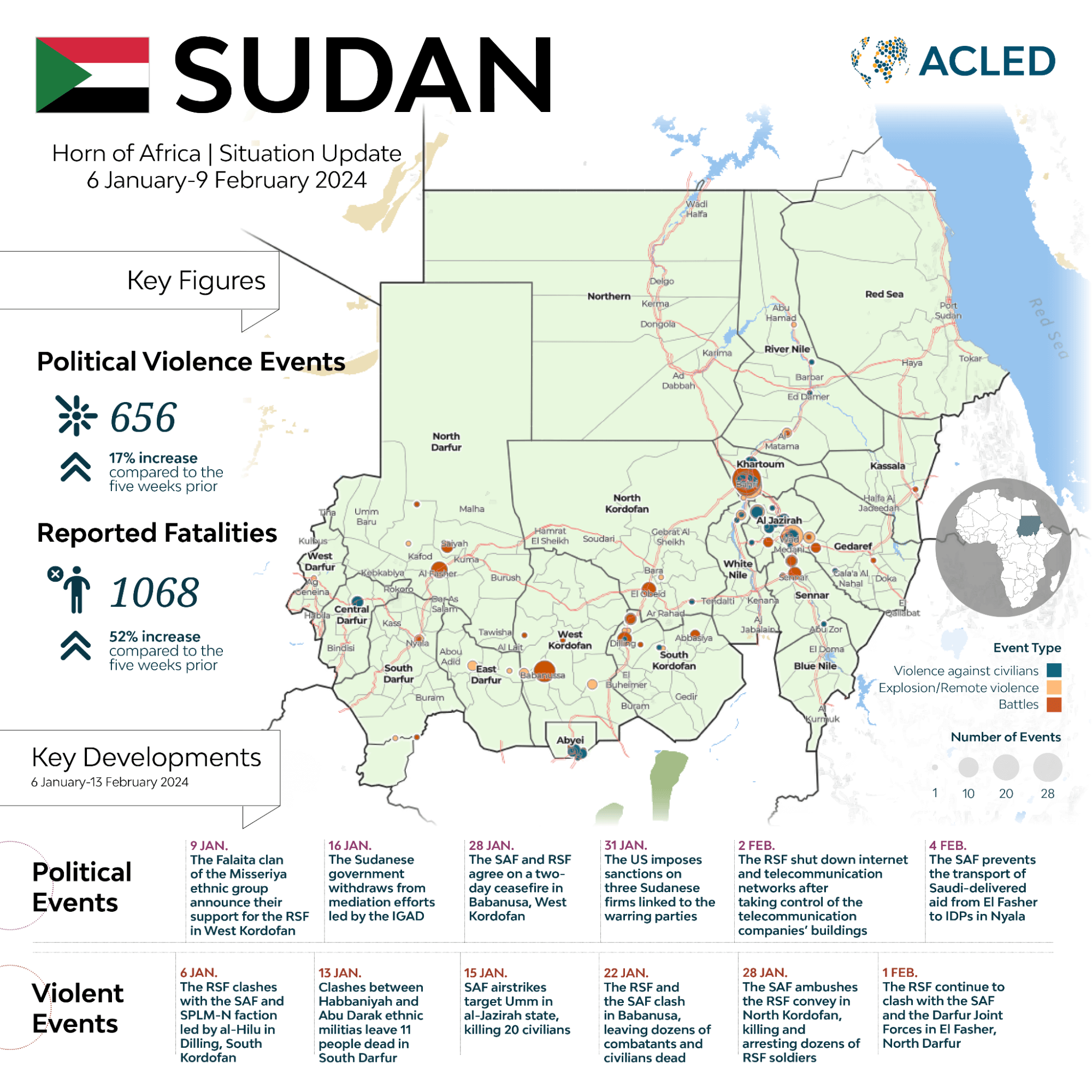

Sudan at a Glance: 6 January-9 February 2024

VITAL TRENDS

- Since fighting first broke out between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) on 15 April, ACLED records over 5,000 events of political violence and more than 14,600 reported fatalities in Sudan.

- From 6 January to 9 February 2024, ACLED records over 655 political violence events and 1,068 reported fatalities.

- Most political violence was recorded in Khartoum state during the reporting period, with over 440 events and 434 reported fatalities.

- During the reporting period, violent events in West Kordofan were particularly lethal, with 21 events resulting in at least 138 reported fatalities.

The SAF Breaks Siege

Ten months into the conflict between the SAF and the RSF, the war in Sudan has taken a new turn. The fall of al-Jazirah in December 2023 sparked armed mobilization in regions controlled by the SAF, with self-defense militias arming themselves to protect against the advancing RSF. Less than a month later, the SAF transitioned from a tactical defensive mode into an offensive one, regaining territories from the RSF and establishing checkpoints to consolidate its gains around its bases in Khartoum. Notably, the SAF now appears on the verge of breaking the RSF siege on the Engineers Corps in Omdurman, where the SAF has been on the defensive since April 2023. Other gains were made in North Bahri in Khartoum, while mediation attempts by the West Kordofan native administration failed to prevent clashes between the RSF and members of the SAF 22nd Infantry Division in Babanusa. In South Kordofan, a faction of the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-North (SPLM-N) led by Abdelaziz al-Hilu turned to the SAF to repel an RSF attack on Dilling.

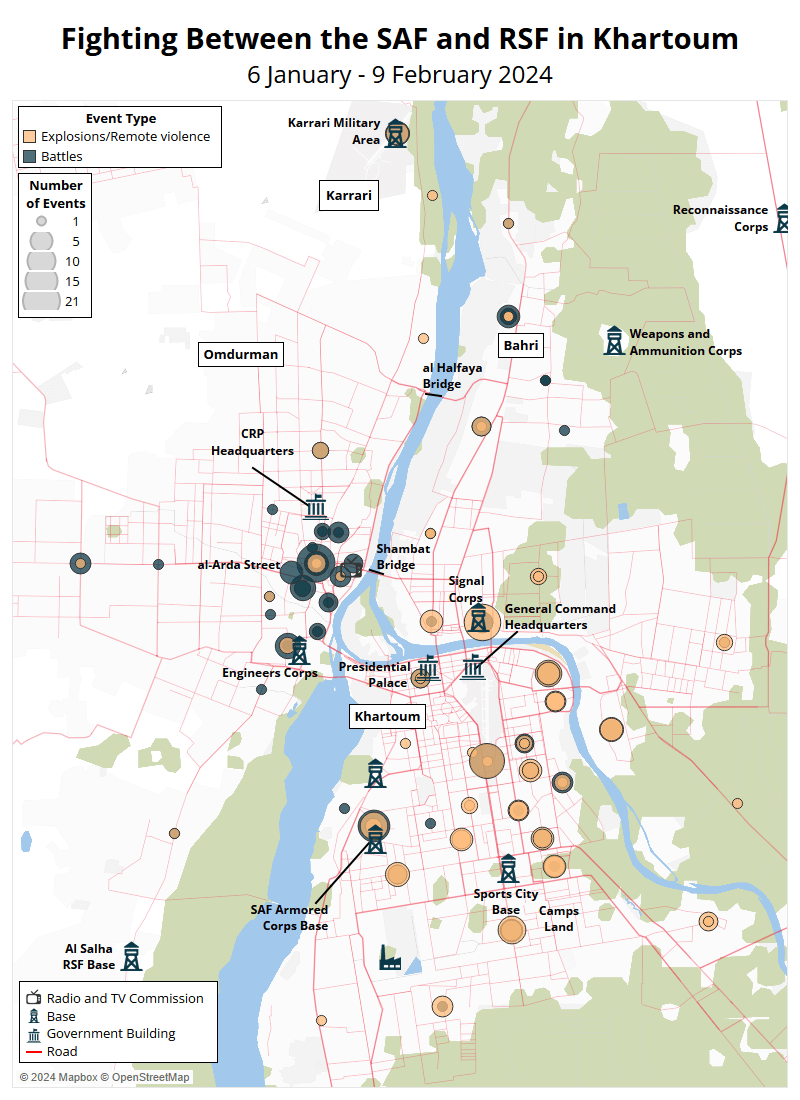

The Fight to Reunify Forces Split in Khartoum

The SAF’s withdrawal from Wad Madani, the capital of al-Jazirah state, in December 2023, attracted widespread criticism against the SAF, including claims that SAF commanders were colluding with the RSF. These losses, however, prompted the formation of self-defense militias and enabled a tactical shift in the SAF from defense to offense. Since April 2023, Khartoum’s metropolitan area has been the epicenter of fighting between the SAF and the RSF, with the former strategically adopting a defensive stance and concentrating its efforts on maintaining control of its military bases. However, in January, the SAF initiated a coordinated offensive against the RSF on various fronts in Khartoum’s tri-cities, reclaiming control over several territories (see map below).

The RSF’s focus on maintaining control in Darfur, al-Jazirah, and other active frontlines, and the isolation of its forces in Old Omdurman, created an opportunity for the SAF to begin its offensive. The first target was the SAF-controlled Engineers Corps military base in south Omdurman. Since the outbreak of the conflict, the RSF has imposed a siege on the base, targeting the SAF troops with artillery and sniper fire. The siege limited the movements of the SAF troops, with the RSF using the surrounding civilian neighborhoods (such as al-Arda and al-Abbasiya) as hideouts. Direct confrontations between the SAF and the RSF were thus limited to frequent exchanges of fire between the two sides.

On 8 January, SAF forces in the Engineers Corps began to attack the RSF in Omdurman, breaking the siege and forcing the RSF into a retreat. However, RSF snipers stationed in the high-rise buildings of al-Arda neighborhood slowed down the attack, preventing the SAF from establishing a direct connection between its troops in north and south Omdurman. Although the RSF command deployed reinforcements in Omdurman, its troops struggled to maintain control over north and south Old Omdurman. Intense artillery fire and drone strikes by the SAF further limited the movements of the RSF.

At the time of writing, the RSF still maintains control over key positions in Omdurman, including al-Arda Street and the Radio and Television Commission building. The goal of the SAF offensive is to link its forces in Omdurman, eventually forcing the RSF out of the city. The RSF may, however, still circumvent the SAF Engineers Corps and impede further SAF advances, thus retaining control over parts of Omdurman. Importantly, the Engineers Corps is numerically and militarily less equipped than other SAF forces in north Omdurman, where the SAF has established its operational command center in Karrari.

Elsewhere in Khartoum, the SAF also mounted an offensive against the RSF in Bahri. At the end of January, SAF troops from the Weapons and Ammunition Corps stationed in north Bahri and SAF troops in the Reconnaissance Corps in northeast Bahri launched coordinated raids against the RSF north of the city. Supported by artillery and shelling from the SAF in Karrari, the SAF expanded its control around these bases and in the surrounding neighborhoods. Meanwhile, besieged members of the SAF in the Signal Corps in south Bahri also claimed to have pushed the RSF back. The SAF’s objective behind these maneuvers might be to cut off RSF forces in the central area of Bahri from their supply route in Sharg al-Nile and besiege them from three fronts — north, east, and south of the city. The RSF forces in the central Bahri area may become isolated as the Shambat bridge, which served as their access point to Omdurman, was destroyed in November 2023. As a result, the SAF might have an opportunity to break the siege on the Signal Corps and, subsequently, the General Command HQ in the northern part of Khartoum city.

The SAF advances in Omdurman mark a potential turning point in the conflict, with the possibility of regaining control over Khartoum’s metropolitan area. If the SAF forces can successfully link up in Omdurman, they may be able to support their counterparts in Bahri, leveraging advances in north Bahri to potentially secure control over both sides of the al-Halfaya bridge. If the SAF is able to link their forces in north and south Bahri, this move would effectively break the siege on the General Command headquarters.

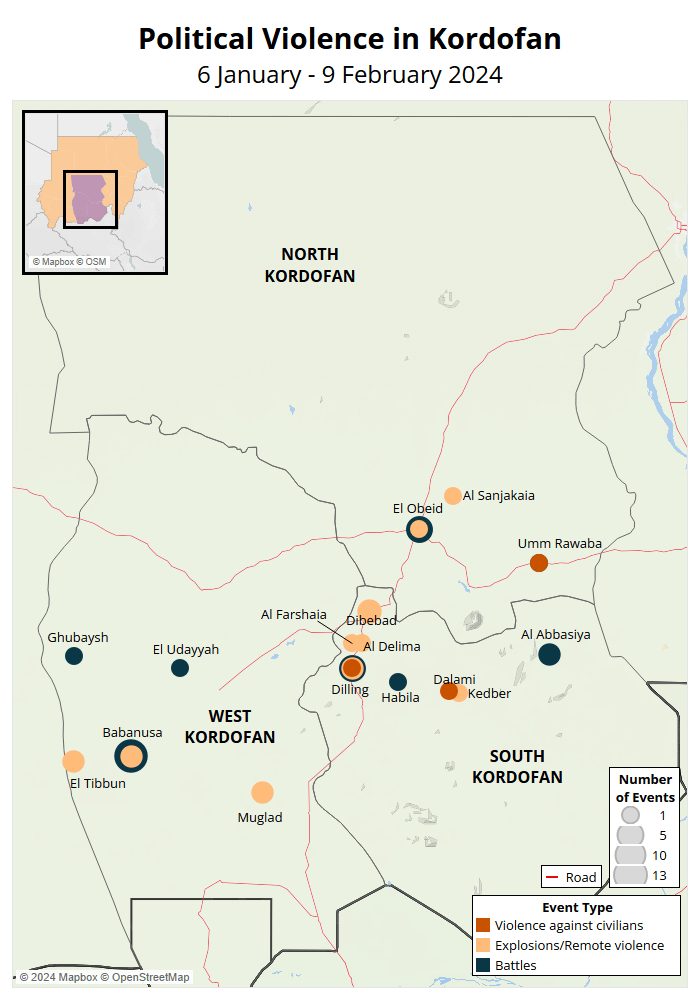

Mediation Failures and Shifting Alliances in Kordofan

In January, Babanusa — a city situated in West Kordofan, near the border with South Sudan — turned into a contested battleground as the RSF attempted to seize control of the SAF-controlled 22nd Infantry Division (see map below). Until November 2023, Babanusa was spared the conflict, mainly due to the dominance of the Misseriya, an ethnic group with historical ties to both the SAF and the RSF. Before and after the independence of South Sudan, the SAF recruited the Misseriya to fight the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army (SPLM/A) and the al-Hilu faction of SPLM-N, respectively.1The Human Security Baseline Assessment for Sudan and South Sudan, ‘Remote-control breakdown Sudanese paramilitary forces and pro-government militias,’ 27 April 2017 Most recently, a significant portion of RSF fighters were recruited from the Misseriya ethnic group, often leading to the targeting of all ethnic Misseriya by the SAF.2Redress, ‘Sudan News Updates,’ 23 June 2023 After the conflict erupted in April 2023, the SAF military intelligence classified the Misseriya tribe as supporters of the RSF in June, leading to increased tensions and targeting of Misseriya.3Radio Dabanga, ‘Young Misseriya targeted, 12 more rape cases reported in Sudan capital,’ 12 June 2023. The designation sparked clashes between the Reserve Forces Eagles Brigade — a Hamar ethnic militia created by the SAF on 29 August — and militants from the Awlad Mansour clan of the Misseriya ethnic group in Umm Kaddada. The fighting tapped into long-standing land disputes between the Hamar and Misseriya ethnic groups in Kordofan that escalated in 2022.4Radio Dabanga, ‘Sudan’s Hamar demand new state of Central Kordofan,’ 4 October 2022

Against this backdrop is the power struggle between the SAF and the RSF. In November, SAF troops withdrew from six bases in West Kordofan, likely facilitated by the Misseriya native administration to avoid tensions between the SAF and the RSF.5Radio Dabanga, ‘Sudan capital witnesses fierce fighting again, airstrikes reported from West Kordofan,’ 6 November 2023 On 29 November, an agreement was signed between the SAF and the RSF to stop armed clashes and airstrikes in the city.6Radio Dabanga, ‘West Kordofan ‘tripartite truce’ violated after less than a day,’ 1 December 2023 However, on 30 December, 22 Misseriya leaders opposed the prospected removal of the SAF from Misseriya lands, as they considered that the fall of the 22nd SAF Infantry Division would leave West Kordofan without protection from cross-border raids.7Sudan Tribune, ‘Misseriya leaders warn of invasion, oil damage in RSF assault on W. Kordofan garrisons,’ 13 January 2024 Complicating matters even further, the close ties between Misseriya soldiers in both SAF and RSF led to multiple defections from the SAF to the RSF.8X @RSFSudan, 15 January 2024 In January, some clans of the Misseriya ethnic group declared their support for the RSF, while others opposed this decision, threatening to fight the RSF if the force attempted to take control of Babanusa.9Sudan Tribune, ‘Tension erupts within Misseriya tribe over RSF’s plans to seize West Kordofan,’ 12 January 2024

SAF airstrikes began to target the RSF in El Tibbun, west of Babanusa, on 13 January. In turn, on 15 January, the RSF mobilized significant forces in various directions around Babanusa, including in El Tibbun, Samoaa in the southwest, and Muglad in the south. The RSF launched an offensive on 22 January, targeting the 22nd SAF Infantry Division. The clashes continued for two weeks, during which the RSF gained control over multiple locations in the city — including several police stations — and released videos from inside the 22nd SAF Infantry Division. The SAF managed to later repel the RSF from the base. The clashes in Babanusa left at least 100 people dead and displaced another 45,000 people.10Sudan Tribune, ‘Over 45,000 people flee ruined West Kordofan’s city,’ 28 January 2024 Fighting continued despite a two-day ceasefire facilitated by the Misseriya native administration on 28 January, which was intended to allow civilians trapped in conflict areas to relocate to safer locations.11Sudan Tribune, ‘Misseriya leaders broker truce to allow civilians to escape conflict zone in Babanus,’ 31 January 2024

In South Kordofan, factional and ethnic divisions also intersect with the national war. Shifting alliances emerged in the city of Dilling, where the al-Hilu faction of the SPLM-N militarily supports the SAF. Communities in South Kordofan have splintered during the conflict, with the Arab tribes — particularly the Hawazmah — aligning with the RSF. The Nuba ethnic group has also split along factional lines, between clans supporting SAF and those siding with Abdelaziz al-Hilu, the long-time leader of a faction of the SPLM-N. The al-Hilu faction has controlled some parts of South Kordofan since 2012.

Al-Hilu’s faction has expanded its control over South Kordofan since the outbreak of the conflict in April 2023. However, the RSF advanced in the region, threatening the power of the al-Hilu’s faction. In December, the town of Habila, 50 kilometers to the east of Dilling in the Nuba mountains, fell to the RSF which formed a local administration in the locality.12Radio Dabanga, ‘Hunger in South Kordofan’s Dalami as calm returns after fighting,’ 28 January 2024 Reports also emerged of targeted violence carried out by RSF fighters against members of the Nuba ethnic group.13X @Halayalkarib, 4 January 2024. The SPLM-N faction under the leadership of al-Hilu joined the SAF on 6 January to defend Dilling from other RSF attacks.14Sudan Tribune, ‘Sudanese joint forces repel fresh RSF attack on South Kordofan’s town,’ 10 January 2024

The outbreak of fighting around Dilling ignited inter-ethnic violence. While al-Hilu’s intervention is more likely aimed at preserving its areas of control rather than seizing Dilling, several neighborhoods affiliated with the RSF-aligned Hawazmah tribe in Dilling were reportedly burned by SAF and al-Hilu as retribution for the tribe’s support to the RSF. The RSF accused the SAF and the SPLM-N-al-Hilu of ethnic cleansing against the Hawazamah.15Sudan Tribune, ‘Dilling town falls to SPLM-N in South Kordofan,’ 7 January 2024 The violence persisted for several days, with the SAF and SPLM-N-al-Hilu pounding RSF positions and in Dilling.

These developments highlight the multiple intersecting layers of the war in Sudan. From Darfur to Kordofan, ethnic divisions intersect with the national war between the SAF and the RSF, igniting or escalating existing inter-ethnic tensions. In West Kordofan, the RSF’s insistence on overtaking Babanusa may prompt the fragmentation of the Misseriya tribe, whose members maintain ties with both the SAF and the RSF.

For its part, the SPLM-N’s al-Hilu faction’s support for the SAF in Dilling mirrors a decision made by the Abdul Wahid al-Nur faction of the Sudan Liberation Movement/Army (SLM/A) to deploy forces in North Darfur when it faced the RSF in November (for more, see the December 2023 Sudan Situation Update). The mobilization of rebel groups and ethnic militias in North Darfur forced the RSF to avoid a direct confrontation. In Kordofan, a sustained collaboration between the SAF and al-Hilu may push the RSF out of Dilling and other areas where the al-Hilu faction of the SPLM-N holds sway. However, clashes between these collaborators elsewhere in South Kordofan add to the uncertainty of the situation.