Still Under Fire:

The Evolving Fate of Civilians in Ukraine

22 February 2024

While battle lines changed only slightly in the second year of the war, ACLED data suggest that civilians continue to be exposed to an extremely high and persistent risk of violence. The shifts in territorial control by the end of 2022 determined hotspot patterns in the second year of the war. However, seemingly static frontlines and falling civilian fatality numbers do not translate into the war being frozen.

While fatality numbers dropped 70%, the risks to civilians have evolved: Proximity to areas directly affected by hostilities was an important but not decisive factor, as civilians faced constant threats both near the frontlines and in the hinterlands, including in Kyiv and along the Black Sea. Unable to rout Ukrainian forces along the frontline, Russia retained its ability to strike Ukraine’s hinterlands at will, with missiles and especially drones — rendering civilians anywhere in the country insecure at all times. Russia’s bombing of Ukrainian ports and grain infrastructure points to the unchanged willingness to inflict civilian hardship, even if other than death or injury. At the same time, the reality for civilians in Russia-controlled areas is unclear as not much information gets out, but what little does suggests a tight grip to consolidate control.

Introduction

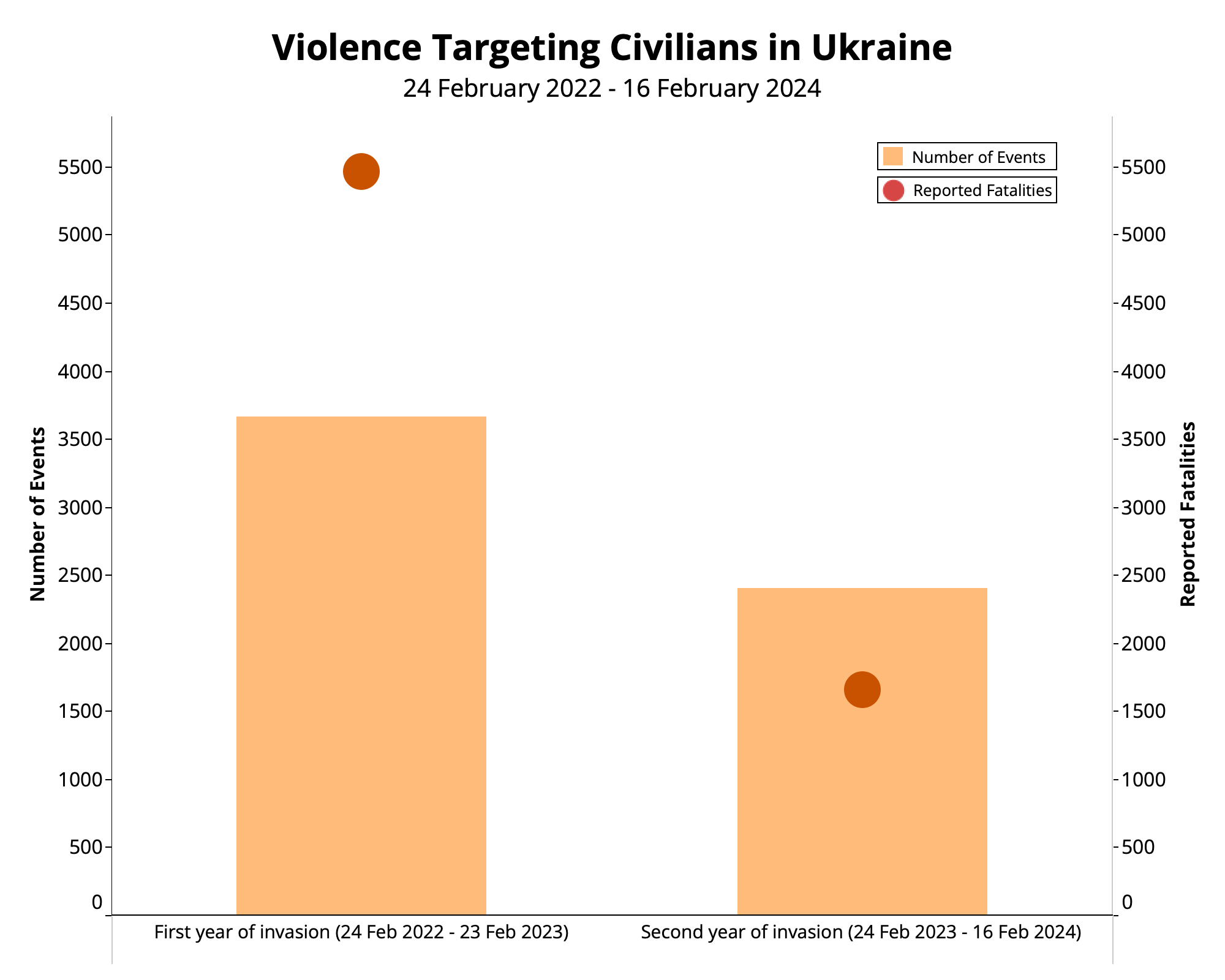

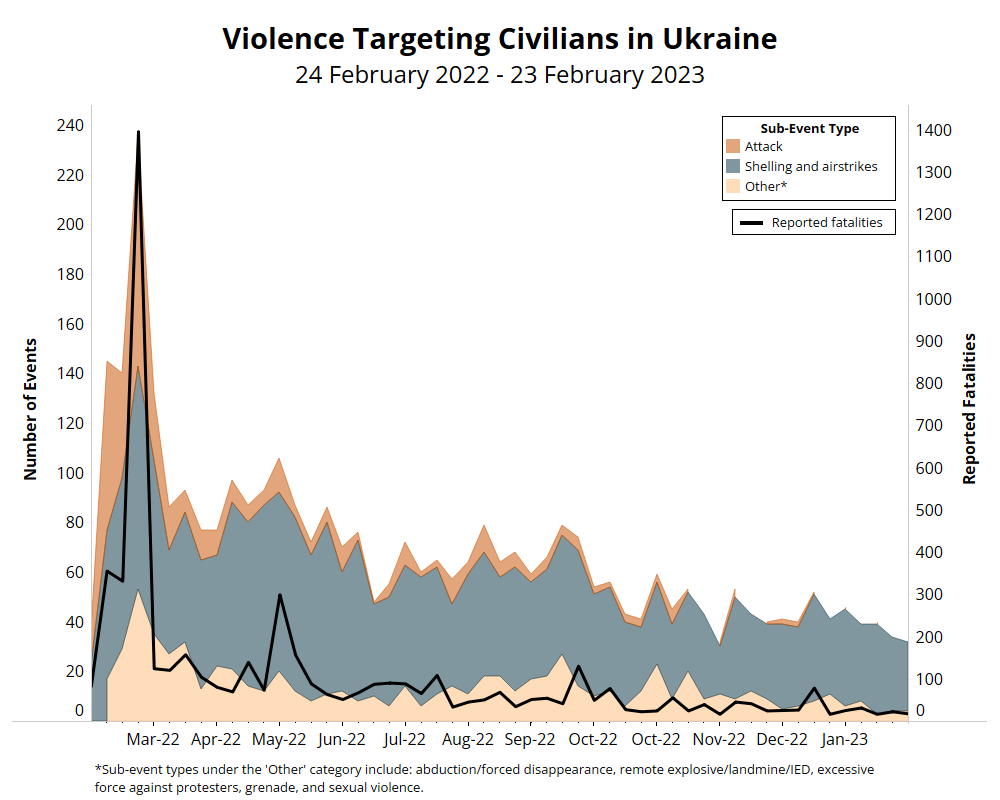

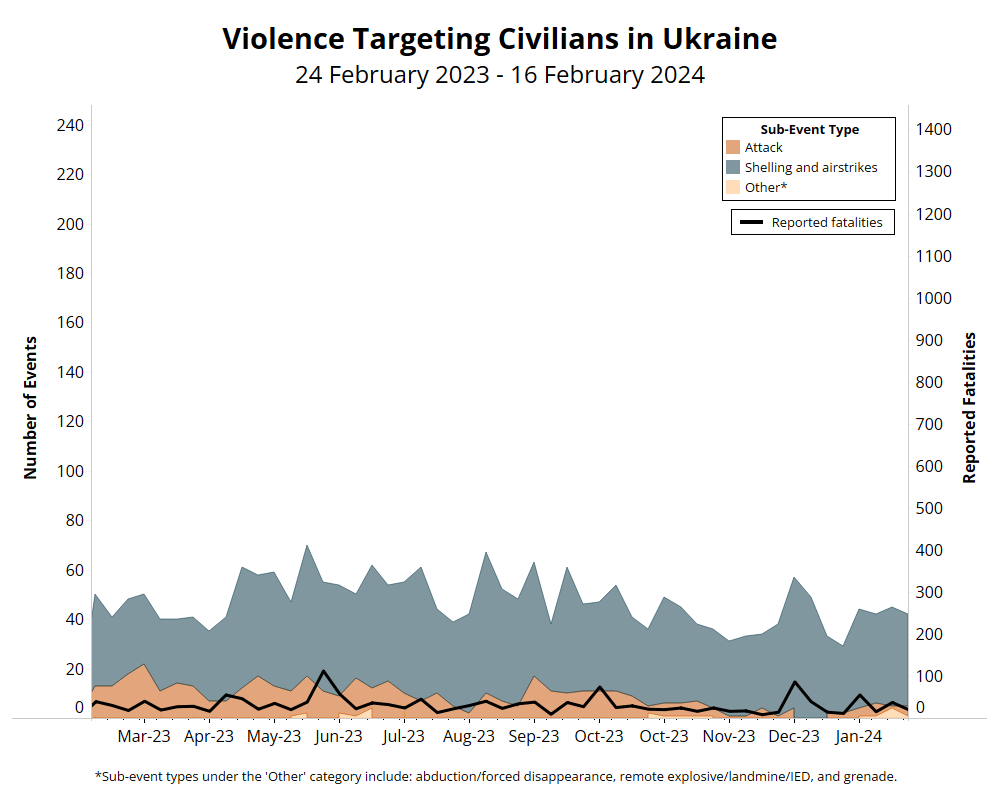

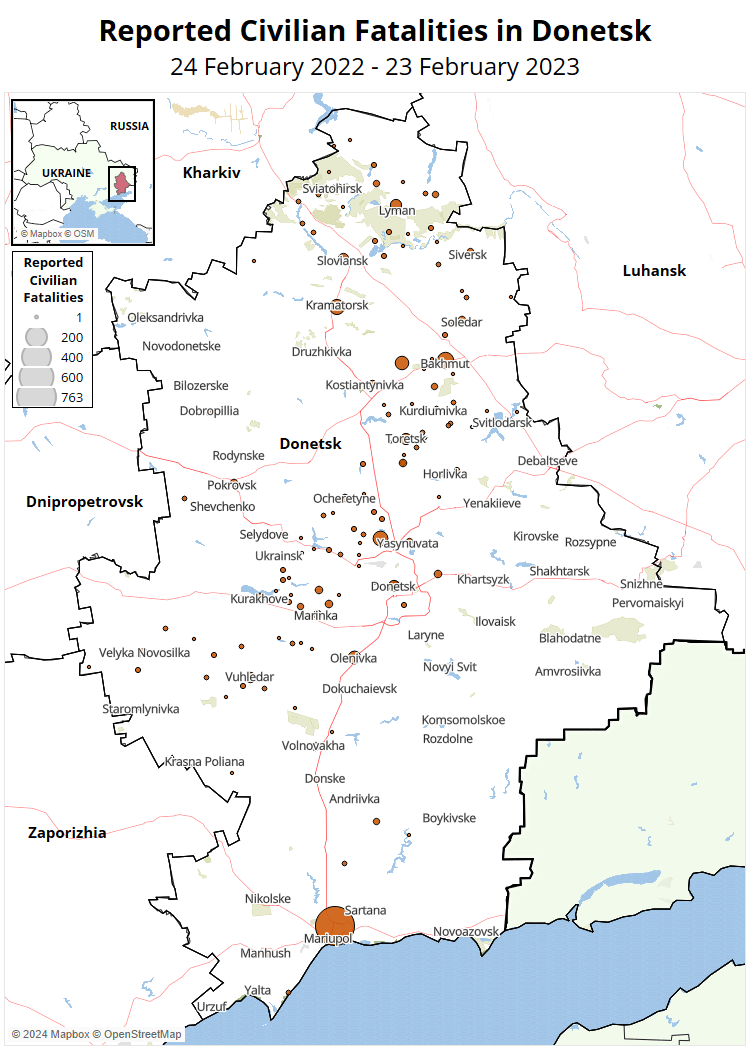

Fatigue from the positional war and proliferating crises elsewhere seem to diminish interest in Europe’s major conflict. The latest edition of the ACLED Conflict Index ranks Ukraine below 12 other flashpoints across the world, from Myanmar to Iraq, despite the persistent deadliness of the violence. The initial shock of Russia’s invasion exacted a high toll on civilians — more than 5,400 reportedly died in the first year of the war,1The first year covers recorded events from 24 February 2022 through 23 February 2023. The second year covers events from 24 February 2023 through 16 February 2024. resulting from over 3,600 violent events in which civilians were the sole or main target (see graph below).2See the Appendix for a regional breakdown of the change in civilian targeting events year-on-year. Over three-quarters of these civilian deaths occurred in the first six months. In contrast, over the course of the second year, ACLED records over 1,600 reported civilian deaths and a nearly 35% decrease in civilian targeting.

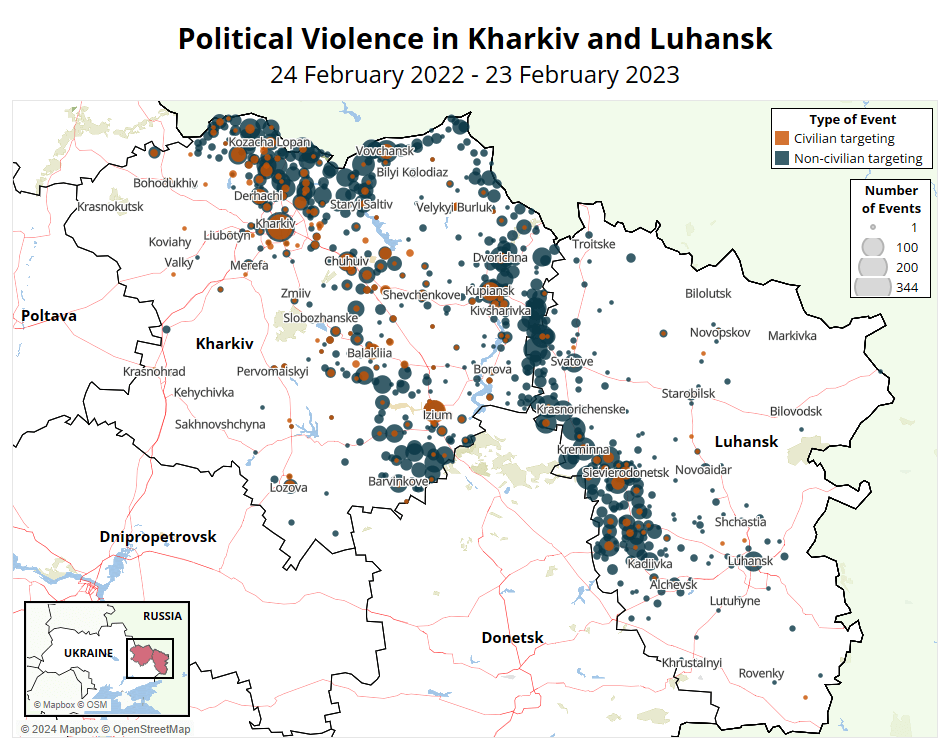

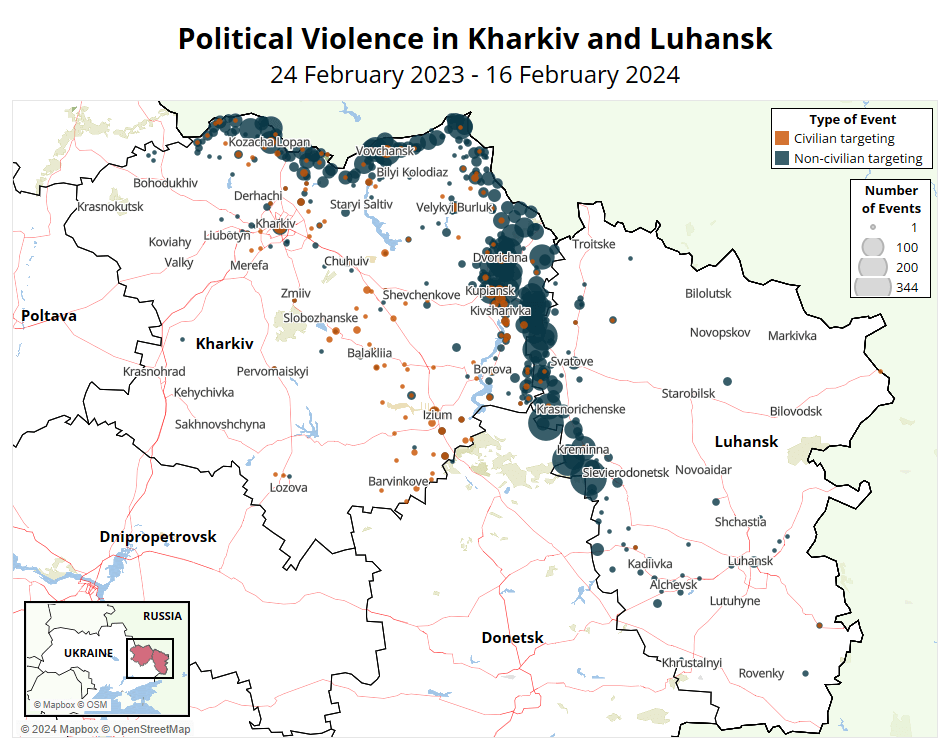

The fact is, the war in Ukraine shows no signs of abating, as the deadlock on the frontlines does not translate to a lack of activity (see maps below). ACLED records over 600 events involving changes in territorial control during the first year of the conflict, evenly distributed between the two sides.3ACLED records a change in territorial control as the control over entire settlements that lasts for longer than 24 hours as opposed to tactical advances. Additionally, in the first year, Ukraine regained control over 110 settlements following Russia’s withdrawals from areas around Kyiv and Kherson in April and November 2022, respectively. In the second year of the war, there were only 22 territorial gains by Ukraine and 31 by Russia, while no voluntary transfers of territory occurred. Now mostly confined to Ukraine’s east and south, the fight is actually getting fiercer: Nearly 9,700 battle events were recorded in the second year of the war — 32% more than in the previous year, mostly due to an intensification of the fighting in the Donetsk and Zaporizhia regions — both the focus of Ukraine’s failed counter-offensive.4Washington Post, ‘In Ukraine, a war of incremental gains as counteroffensive stalls,’ 4 December 2023

With the battlefield deadlocked, fewer people faced the prospect of often lethal encounters with invading Russian forces, which caused about a quarter of all conflict-related civilian deaths. In the second year, ACLED records a 92% decrease in the number of such attacks. Encounters with the invading forces, however, remained a threat. Russian forces committed 30 of the 36 recorded attacks against civilians and caused 45 of the 46 reported fatalities, mostly in the occupied parts of the Kherson and Zaporizhia regions, including extrajudicial executions of surrendered or surrendering Ukrainian personnel.

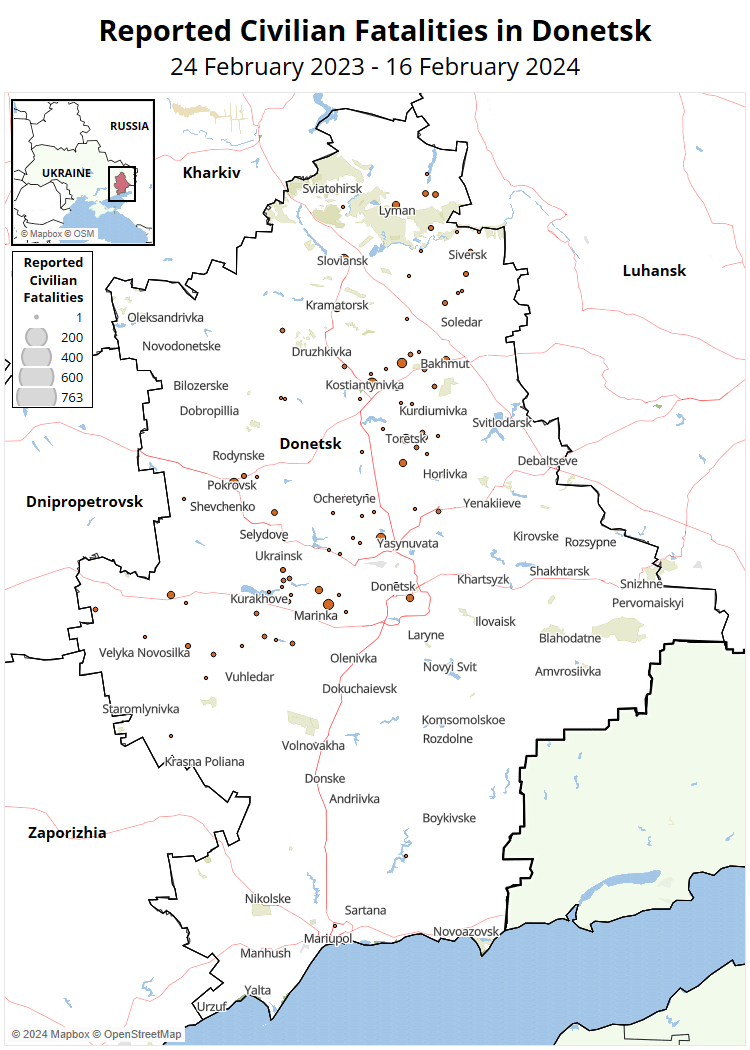

Indiscriminate shelling, air and drone strikes on populated areas continued to claim civilian casualties. The overall number of these events fell by 20% in the second year of the invasion, while the number of resulting fatalities decreased from over 3,800 to nearly 1,400 (see graphs below). There were clear spikes in the number of civilian targeting events in the wake of and during the Ukrainian counter-offensive in May to September, at the start of Russia’s counter-attack along the frontline in October, and the increased tempo of Russia’s bombing campaign further away from the battlefield since December. Indiscriminate targeting led to 84% of the reported civilian fatalities, averaging about 135 a month, most of them in frontline regions. Nonetheless, proximity to areas of active hostilities was an important but not decisive factor.

This study examines how civilians in areas along the frontlines and Ukraine’s hinterlands have experienced the second year of war. Despite the deadlock in fighting, the threats to civilians persisted, albeit somewhat mitigated by changes in territorial control a year earlier and greater predictability of the battlefield. Meanwhile, the risks in areas further away from active hostilities continued due to Russia’s ability to conduct air raids deep inside the country. Civilian experiences in the Russia-occupied areas are most difficult to gauge due to tight controls on information there, while the outlook of the war entering its third year does not bode well for Ukraine’s embattled civilians.

Unrelenting Risk in the Frontline Regions

Ongoing cross-border strikes had less impact on civilian populations in the liberated parts of northeastern Ukraine in the second year of the war. Intensifying but largely static battles in the Donetsk and Zaporizhia regions likewise did not translate into an increase in the number of civilian targeting events. Paradoxically, the liberated part of the Kherson region accounted for most civilian targeting events despite not seeing major fighting due to the destruction of a critical dam, which prevented any offensives but posed an extreme and long-term threat to civilians. While the changes of territorial control in the previous year defined civilian experiences in Ukraine’s northeast and south, the stalemate in the second year put remaining civilians at constant but relatively predictable risk.

Northeastern Ukraine

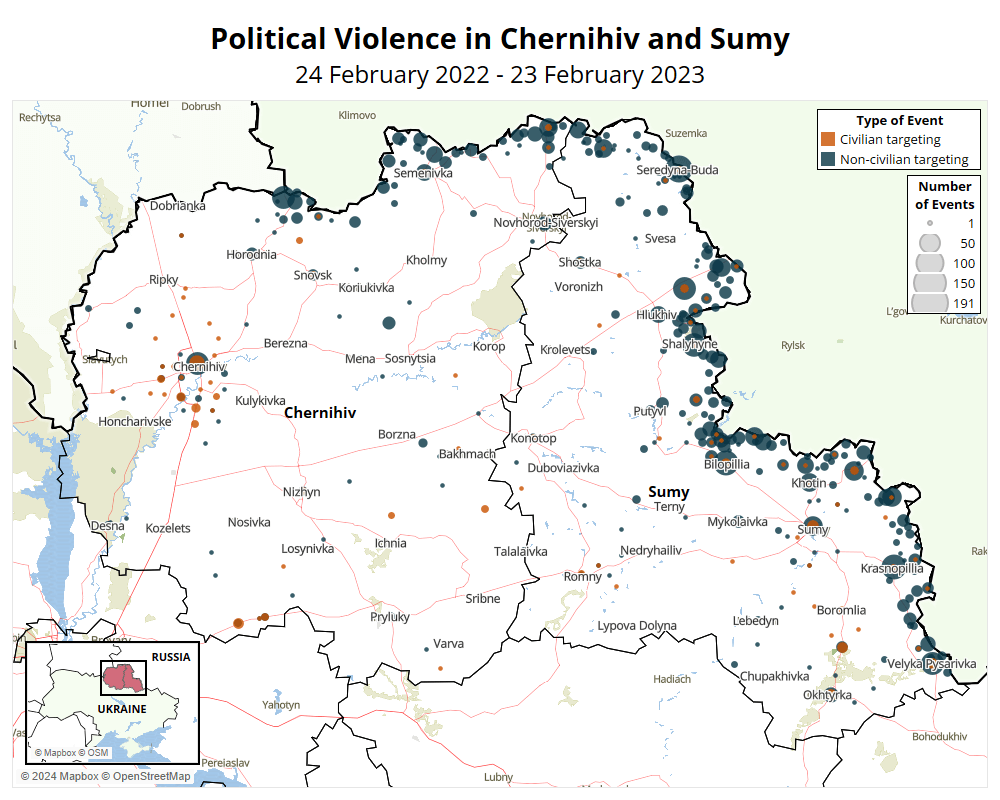

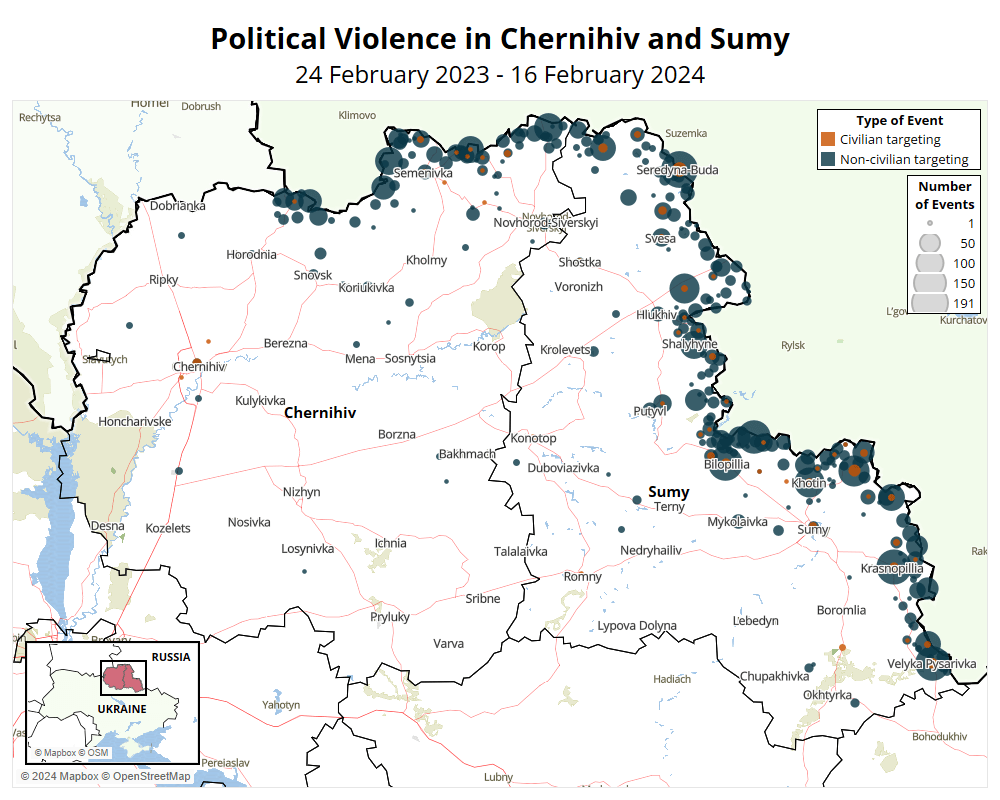

In Chernihiv and Sumy — two northeastern regions that Ukraine recovered in spring 2022 — political violence grew by 53% and 88% during the second year of the war, respectively, due to frequent shelling and airstrikes. They did not, however, much affect civilians as the artillery and drone exchanges occur mostly in the sparsely populated areas along the border (see maps below).5Map Action, ‘Population Density by Raion (based upon WorldPop population counts for 2020),’ 8 March 2022 This led to a 73% decrease in the number of reported civilian fatalities, from over 330 people killed during the first year of the invasion, of whom a third were killed in direct attacks by the Russian forces. Though mostly confined to border areas, the threat of indiscriminate shelling remained very real for population centers. For instance, a Russian missile strike on 19 August 2023 on the Chernihiv city’s opera house hosting a gathering of drone designers and manufacturers killed seven civilians and wounded over 150 others. The strike is indicative of Russia’s willingness to target the brainpower behind Ukraine’s grassroots drone design and assembly effort.6Ulrike Franke and Jenny Söderström, ‘Star tech enterprise: Emerging technologies in Russia’s war on Ukraine,’ European Council on Foreign Relations, 5 September 2023

ACLED records the sharpest decreases in the number of civilian targeting events in the Luhansk (-88%) and Kharkiv (-65%) regions (see maps below). Russian forces captured practically the entire Luhansk region by July 2022, but withdrew in disarray from most of the Kharkiv region in the fall of that year. Little information has transpired from the Luhansk region despite being the frequent target of Ukrainian long-range missile and drone strikes at concentrations of Russian military hardware and personnel, with civilians occasionally caught in the crossfire. The fighting on the boundary between Luhansk and Kharkiv has persisted, with Russian forces threatening Kupiansk as part of their ongoing winter 2024 offensive. Despite violence being mostly contained to border areas, Russian artillery shells Kharkiv city — the second largest in Ukraine — from across the border on a nearly daily basis amid an ongoing standoff with Russia’s Belgorod region. The deadliest single mass civilian fatalities event in the second year of the invasion — a Russian missile strike on the village of Hroza on 5 October that killed 59 civilians — also placed Kharkiv among the top three most dangerous regions for civilians in Ukraine.

Donetsk and Zaporizhia

The Donetsk region has seen one of the most dramatic conflict escalations since the summer of 2022. Violence reached all-time peaks in March, July, and December 2023, despite civilian targeting and related fatalities dropping year-on-year by 20% and 74%, respectively. Indiscriminate shelling and airstrikes reportedly killed over 400 people during the second year of the conflict. The Russian tactic of ‘liberating’ settlements by leveling them to the ground could have persuaded remaining civilians to leave early. Nevertheless, about a quarter of all civilian deaths recorded in the second year still occurred in and around Bakhmut, pointing to a still significant civilian presence even in areas of fierce fighting (see maps below). The ruins of Bakhmut continue to be contested despite its capture in late May by the now seemingly defunct Wagner Group.7Ilya Barabanov and Anastasiya Lotareva, ‘The Bearded Circus Ongoing for a Year and a Half. Whereto are PMC Wagner fighters leaving,’ BBC, 2 November 2023 Meanwhile, over 140 civilians died in likely Ukrainian shelling of Russian positions in sprawling boroughs of Donetsk city, which lies practically on the line of contact. In the deadliest single incident in the city since the start of the Russian invasion, 28 civilians were killed, and at least 30 others were wounded in an artillery strike on a market on 21 January 2024. The sides traded accusations, but no independent investigation into the incident is underway amid Russia’s ongoing offensives north and west of the city.8Matthew Mpoke Bigg, ‘Deadly Blast Hits Market in Ukrainian City Controlled by Russia, Officials Say,’ New York Times, 21 January 2024

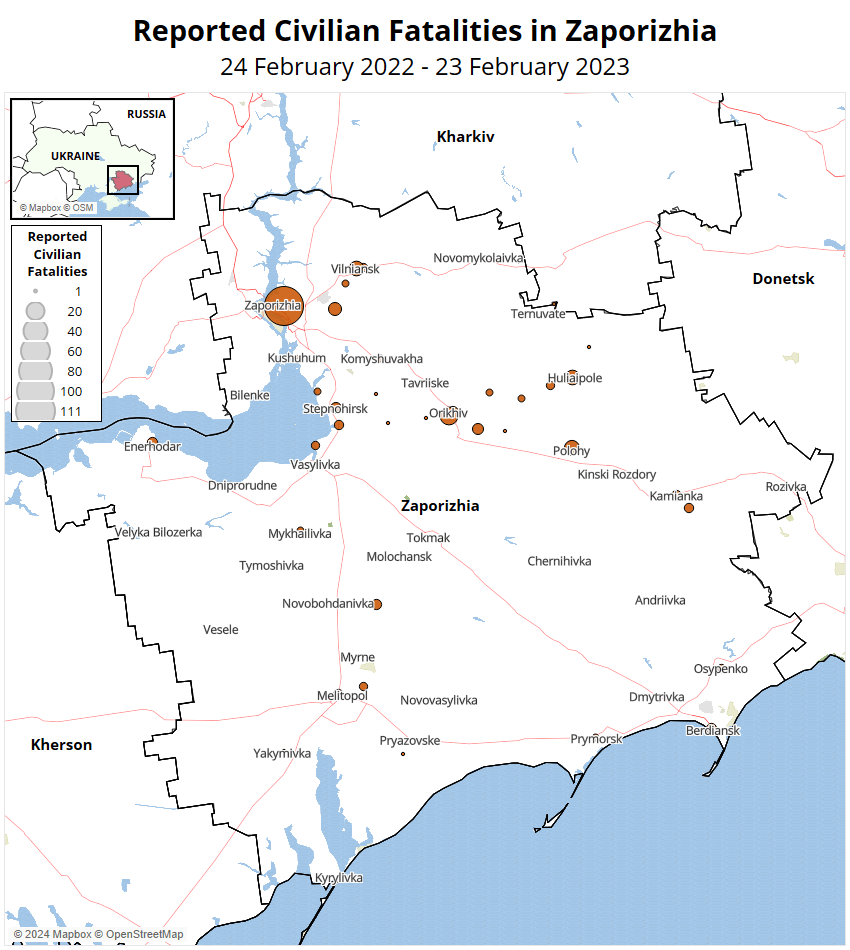

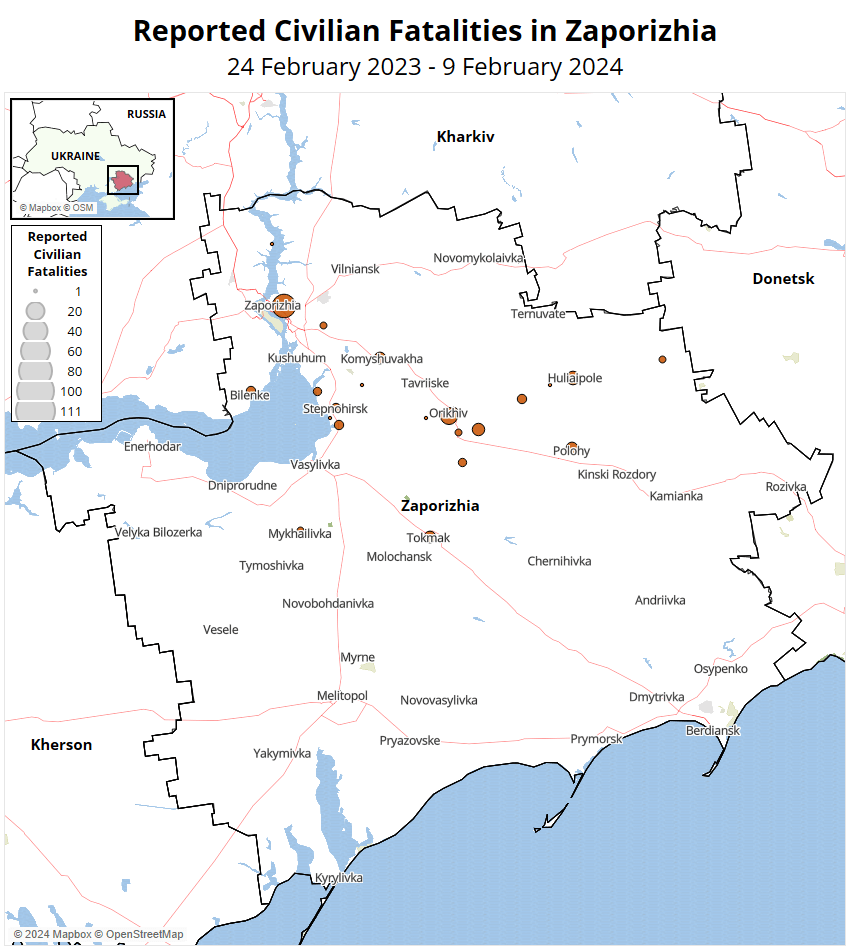

A similar trend was observed in the Zaporizhia region. Despite being the focus of the Ukrainian attempt to liberate the larger part of the region under Russian occupation in summer, civilian targeting fell by an estimated 41% in the second year, and the number of civilian fatalities nearly halved (see maps below). Most resulted from indiscriminate shelling and airstrikes. Ukrainian forces were involved in only two events and two resulting civilian fatalities. The distance from the frontlines of Russian-occupied towns in the region (particularly Melitopol) likely contributed to the rare civilian targeting, as Ukrainian forces found themselves unable to break through layers of Russian fortifications and minefields, and the exodus of locals in the initial stages of the invasion. Areas around the government-controlled city of Zaporizhia and the smaller towns of Orikhiv and Huliapole were most affected by Russian shelling, with a clear spike in June.

Kherson

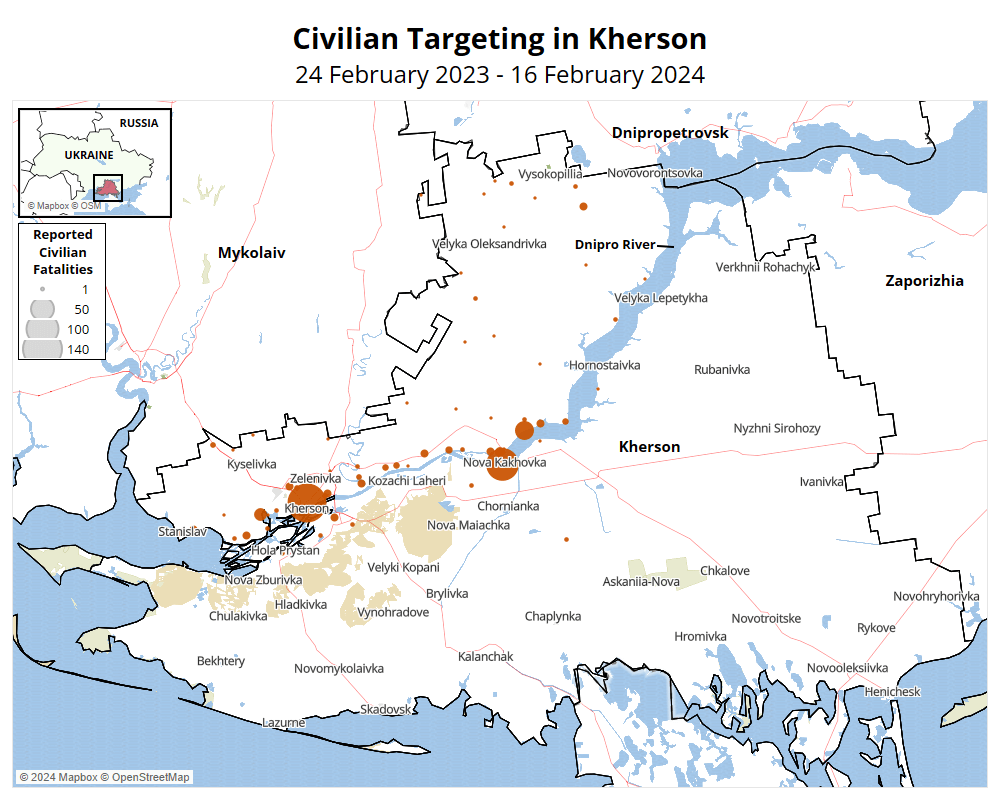

The Kherson region and its smaller outpost on the western bank of the Dnipro river were subjected to most civilian targeting in the second year of the invasion, despite an overall decrease in the number of armed clashes since Russia’s withdrawal across the river in November 2022. The morale boost for the Ukrainian side from the recovery of Kherson city — the sole regional capital Russia captured in 2022 but was unable to hold — proved short-lived as increasing shelling on residential areas continued to claim a high number of civilian casualties. Kherson is second only to the highly kinetic Donetsk region in terms of reported civilian fatalities, with the capital city and its suburbs reporting over 230 civilian deaths in the second year of the war (see map below). In one of the deadliest instances, repeated Russian shelling of Kherson city on 3 May and environs killed 24 civilians and injured scores of others. The shelling intensified in October as small groups of Ukrainian forces established footholds on the Russian-occupied eastern bank of the Dnipro river. About 150,000 residents were found in Kherson upon Russia’s retreat, a city that had a pre-war population of 300,000.9Andriy Kuzakov, ‘’We Realized That We Still Had To Fight’: Life In Kherson One Year After The End Of Russia’s Occupation,’ Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty, 11 November 2023 Now, more than half have fled due to constant shelling, with mostly elderly people left behind.10The Economist, ‘A year after its liberation, Kherson still knows fear—and defiance,’ 9 November 2023

Kherson city also experienced the highest number of strikes on health care facilities in the second year of the war, succeeding the contested Kharkiv region. Health care workers are indeed among the most frequently targeted groups in Ukraine, along with farmers and utility workers who face the threat posed by landmines and explosive remnants of war and shelling during repairs to civilian infrastructure. The continued targeting of health care facilities adds to the plight of the civilian population, many of whom are likely confronted with medical conditions due to age and require medical attention and inpatient care.

An even greater challenge for both liberated and larger occupied parts of the Kherson region was the destruction of a dam near Nova Kakhovka on 6 June, in what may be one of the first modern examples of provoking a flood for military ends.11Timothy Heck and Zachary Griffiths, ‘When the Levee Breaks: Five Military Takeaways from the Kakhovka Dam’s Destruction,’ Modern War Institute, 8 June 2023 The dam was located between the warring parties’ positions on either side of the Dnipro river, with Russian forces in control of the nearby and underwater hydroelectric facilities.12Maksym Savchuk et al., ‘Ready! All by orders! Russian troops in charge of the Kakhovka hydroelectric station identified. Exclusive intercepts,’ Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty and Slidstvo Info, 28 June 2023 Russia denied responsibility for causing the collapse, despite the flood occurring in the wake of the Ukrainian summer 2023 counter-offensive and a decree issued shortly before the disaster, putting on hold investigations of damage to infrastructure in areas subjected to hostilities.13Decree of the Government of the Russian Federation of 30.05.2023 No.873 ‘On particularities of applying the provisions of the legislation of the Russian Federation on industrial safety at perilous industrial sites and ensuring safety at hydrotechnical facilities on the territories of the Donetsk People’s Republic, Luhansk People’s Republic, Zaporizhia and Kherson regions’ At least 31 civilians were reported drowned in areas under Ukrainian government control and another 59 in Russian-occupied areas. However, Russian occupation officials’ tally is believed to be a severe undercount.14Samya Kullab and Illia Novikov, ‘Russia covered up and undercounted true human cost of floodings after dam explosion,’ Associated Press, 28 December 2023 There were also multiple civilians injured and several killed, including emergency workers and volunteers, due to Russian shelling during evacuation efforts in the immediate aftermath of the flood. The repercussions for the local ecosystem as well as a likely increased threat from displaced mines, including in the Black Sea, are still being assessed.

The emptying of the Kakhovka water reservoir did not affect the Zaporizhia nuclear power plant (ZNPP), located upstream further east, though it may soon run out of luck. Occupied by Russia and exploited for nuclear blackmail, it is now severely understaffed and experiences frequent power outages, increasing the risk of accidents.15Samya Kullab, ‘UN nuclear chief says security is still fragile at Ukraine’s Russian-occupied nuclear power plant,’ Associated Press, 6 February 2024 International efforts to negotiate a security zone around it led nowhere, although International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) staff monitor compliance with safety protocols.16International Atomic Energy Agency, ‘Update 152 – IAEA Director General Statement on Situation in Ukraine,’ 30 March 2023 Meanwhile, Crimea is again experiencing water shortages. In the early stages of the occupation of the Kherson region, Russia reopened the North Crimea canal, which Ukraine had closed in response to Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014. The closure led to frequent water crises on the arid peninsula. The Russia-provoked flood ended a 15-month-long relative abundance.

Beyond the Conflict Hotspots

Deadlocked at the frontline, Russian forces retained their ability to target practically any area of Ukraine. The key difference in the second year of the invasion was the scaled-up use of Iranian Shaheds-series attack drones directed at less defended targets further away from the frontline.17Airwars, ‘Reported Shahed drone launches in Ukraine: August 2022-September 2023,’ 8 September 2023 Russia extensively used these drones during its explicit targeting of Ukraine’s energy infrastructure in the winter of 2022-23. It resulted in extreme hardship for civilians, causing frequent power outages with domino effects on gas, heating, and water supply.18Human Rights Watch, ‘Ukraine: Russian Attacks on Energy Grid Threaten Civilians,’ 6 December 2022 Contrary to expectations, Russia has not resorted to a campaign of similar scale in the cold season of the second year of the war; though Ukraine’s energy grid may not have fully recovered.19Reuters, ‘Russian air strikes focus on Ukrainian military industry for now – Kyiv,’ 15 January 2024

Western-most regions saw fewer attacks, while strikes on central regions slightly increased, with Russian missiles frequently targeting high-value military targets such as airfields in the central Khmelnytskyi, Kirovograd, Poltava, Zhytomyr, and Dnipropetrovsk regions. In the latter region, production sites in the major cities of Dnipro, Kryvyi Rih, and Pavlohrad were frequently targeted. Russian attempts to suppress the Ukrainian air force and defenses, as well as production capability, led to frequent hits on populated areas deep behind the frontlines. In particular, Russian forces persistently targeted Ukraine’s capital and clearly attempted to stop the country’s agricultural exports via the Black Sea.

Kyiv

After failing to seize Ukraine’s capital city in the first year of the invasion, the Russian military seemingly remained fixated on Kyiv in the second. While violent events in the surrounding Kyiv region dropped by 96% in the aftermath of Russia’s withdrawal in March 2022, they only decreased by 13% in Kyiv city — despite it being one of the most protected places in Ukraine. It was subjected to nearly daily drone and missile strikes in May and early June 2023 as Ukraine was expected to launch its counter-offensive. Kyiv city is more likely to be targeted by sophisticated missiles, including ones with hypersonic capabilities, than any other location in Ukraine, with drones seemingly serving as decoys to pave the wave for incoming projectiles. Kyiv city fell under another barrage of strikes in late December when Russia directed an unusually high number of missiles at various targets in the city. Unlike in May when Russian forces were seemingly attempting to disable Kyiv’s ‘Patriot’ air-defense system protecting the city,20Adam Taylor, David L. Stern and Alex Horton, ‘Ukraine says Patriot air defense system not destroyed,’ Washington Post, 17 May 2023 missile strikes in December overwhelmingly targeted civilians — on 29 December alone, they killed 32 people and injured scores more. Even when intercepted, debris from Russia’s drones and especially missiles pose a significant risk. For instance, 53 people were injured in Kyiv city on 13 December after Ukrainian air defenses intercepted Russian ballistic and surface-to-air missiles. The impossibility of completely insulating Kyiv and other major Ukrainian cities from Russia’s drones and missiles rules out the set-up of large-scale military production and exacerbates Ukraine’s reliance on an external supply of weapons and ammunition.21Kateryna Stepanenko et al., ‘Ukraine’s Long-Term Path to Success: Jumpstarting a Self-Sufficient Defense Industrial Base with US and EU Support,’ Institute for the Study of War, 14 January 2024

The Black Sea

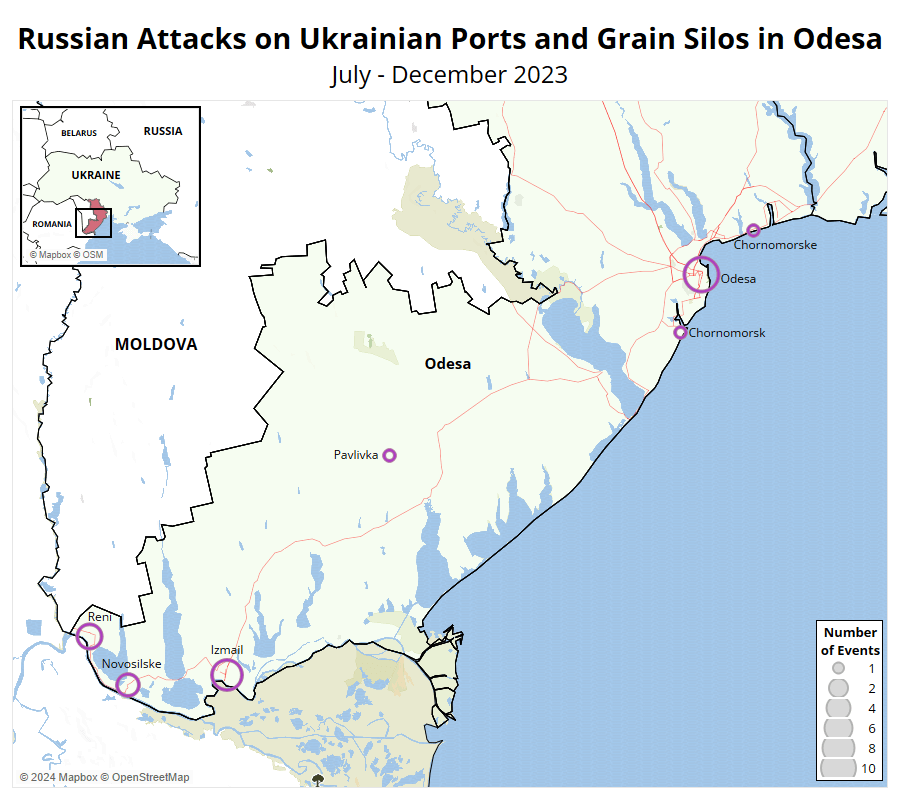

Fighting intensified in areas around the Black Sea in the second year of the war. In mid-July, Russia refused to extend the Black Sea Grain Initiative — a deal struck a year earlier to allow exports of Ukrainian agricultural products to the Global South — and later threatened to fire at any ship heading to or from Ukraine.22Le Monde, ‘Russia threatens Black Sea ships after grain deal exit,’ 20 July 2023 Meanwhile, Russian drones and missiles started to target Ukraine’s ports and grain silos on the Black Sea and the Danube river (see map below). Ports and grain silos are usually located farther away from densely populated areas; therefore, the nearly two dozen drone and missile strikes since July mostly inflicted material damage. Nevertheless, a Russian missile strike on 23 July left scores wounded and severely damaged Odesa city center — a UNESCO World Heritage site.23UNESCO, ‘Odesa: UNESCO strongly condemns repeated attacks against cultural heritage, including World Heritage,’ 23 July 2023 Debris from intercepted or misdirected drones occasionally ended up on Romania’s territory in the closely knit Danube area but did not trigger a NATO response or a threat thereof.

Ukraine called Russia’s bluff and, by late September, rerouted grain ships close to Romania’s shore. Russia stopped and searched a sole foreign civilian vessel at sea on 13 August,24Matthew Mpoke Bigg, Jenny Gross, and Christiaan Triebert, ‘Black Sea Clashes Grow as Russia Fires Warning Shots and Boards a Freighter,’ New York Times, 14 August 2023 fired at a civilian ship in Odesa port on 8 November (killing a sailor), and allegedly scattered mines in the southwestern part of the sea.25Reuters, ‘Ukraine says Russian warplanes drop explosives on Black Sea shipping lanes,’ 1 November 2023 It was unable to deliver on its threat of imposing a full-fledged maritime blockade as Ukraine challenged Russia’s military capabilities in and near Crimea. Violent events there doubled, albeit from a low base recorded in the previous year, with distinct spikes in July and September. This did not, however, lead to a corresponding increase in the number of events targeting civilians. Outgunned and lacking a fleet of its own,26Marc Santora, ‘How Ukraine, With No Warships, Is Thwarting Russia’s Navy,’ New York Times, 12 November 2023 Ukraine probably put out of operation over a third of Russia’s own Black Sea Fleet since the invasion,27Stepan Smyshlyaev, ‘A third of Russia’s Black Sea Fleet out of operation – UAF,’ Deutsche Welle, 6 February 2024 with its strike campaign in the second half of 2023 forcing the relocation of the remaining assets.28Nicole Wolkov, Daniel Mealie, and Kateryna Stepanenko, ‘Ukrainian Strikes Have Changed Russian Naval Operations in the Black Sea,’ Institute for the Study of War, 16 December 2023; Bloomberg, ‘Putin Forced to Relocate Ships in Crimea After Ukraine Strikes,’ 29 December 2023

Russia’s Tight Grip on Occupied Areas

The discussion of the situation of civilians in areas of Ukraine still under Russia’s occupation is severely limited by the little independent information that trickles in. As dug-in Russian forces fended off Ukrainian attempts to recover territory along the 1,000-kilometer frontline, about 18% of the country (including Crimea) remains occupied. The absence of significant recoveries of territory translates into fewer revelations of abuse of civilians, such as the post-liberation discovery of torture chambers in the de-occupied parts of northeastern Ukraine and the city of Kherson in 2022.29Veronika Melkozerova, ‘Calculated evil: How Putin’s forces use war crimes and torture to erase Ukrainian identity,’ Politico, 3 March 2023 Russia has imposed tight informational controls in the areas of Ukraine it occupies by wiping out independent media and installing its own propaganda machine.30Reporters without Borders, ‘Occupied Territories of Ukraine: Russia propaganda machine continues to absorb local media,’ 6 December 2023 International organizations, except the IAEA and the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), do not have access to the occupied areas, which further complicates efforts to retrieve information.31Ukrinform, ‘No international organization has access to occupied areas of Ukraine – ombudsman,’ 23 October 2023

The frontline has completely sealed off the occupied territories from the rest of Ukraine, with only a single and perilous land border crossing from Russia’s Belgorod region into Ukraine’s Sumy region still reportedly available.32Hanna Arhirova, ‘Life in Russian-controlled areas of Ukraine is grim. People are fleeing through a dangerous corridor,’ Associated Press, 12 December 2023 Fewer people can therefore escape the occupied territories and share their experiences. Accounts of the Russian mistreatment of civilians are likely severely underreported but continued to slip through the cracks throughout 2023, including arbitrary executions of civilians and prisoners of war, torture, rape, and abductions across all occupied regions.33United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, ‘Report on the Human Rights Situation in Ukraine, 1 February to 31 July 2023,’ 4 October 2023; United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, ‘Report of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on Ukraine,’ 19 October 2023 In the deadliest incident, on 27 October, in occupied Volnovakha, the Donetsk region, Russian servicemen shot dead a family of nine in their sleep, reportedly due to their earlier refusal to vacate their house.34Nate Ostiller, ‘Prosecutor’s Office: Russian forces murder 9 family members in occupied Volnovakha,’ Kyiv Independent, 30 October 2023

In the second year of the invasion, Russian occupation authorities focused on consolidating control over the ‘new territories’ — a euphemism referring to the occupied parts of the Luhansk, Donetsk, Zaporizhia, and Kherson regions that Russia annexed in September 2022 in response to Ukraine’s surprise liberation of the Kharkiv region.35Andrey Pertsev, ‘Russification Lite,’ Meduza, 3 October 2023 Having put in incommunicado detention thousands of civilians who resisted the occupation,36Olga Prosvirova and Zhanna Bezpyatchuk, ‘We came to liberate you.’ How Ukrainians disappear in Russian penitentiaries,’ BBC Russian Service, 8 January 2024 including scores of local officials, Russian authorities and local collaborators are now attempting to eradicate Ukrainian national identity by outlawing, in practice, pro-Ukrainian views and ‘re-educating’ captive civilians.37Veronika Melkozerova, ‘Calculated evil: How Putin’s forces use war crimes and torture to erase Ukrainian identity,’ Politico, 3 March 2023

Those still enjoying their freedom are expected to assimilate to the Russian language and culture as Russian leadership denies the existence of the distinct Ukrainian ethnicity and language and seeks to make the annexation irreversible. To speed up the process, Russia’s President Vladimir Putin ordered that the residents of the ‘new territories’ take up Russian citizenship before 1 July 2024 or face the prospect of deportation should they be deemed a security threat.38Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty – Russian Service and Current Time, ‘Putin Targets Political Opponents, Ukrainians In Occupied Territories With New Laws,’ 28 April 2023 Even before the deadline, occupation officials are already denying entitlements, basic services, medical care, and medication to Ukrainians who have not received Russian passports.39Yale School of Public Health, ‘Forced Passportization In Russia-Occupied Areas Of Ukraine,’ 2 August 2023; European Broadcasting Union, ‘Russification in Occupied Ukraine,’ 16 November 2023 By the end of September, an estimated 1.5 million out of the 5 million residents of the occupied territories underwent forced naturalization, and the rest are now considered foreigners who should apply for residence permits.40ACAPS, ‘Global Risk Analysis,’ 18 October 2023 The acceptance of Russian citizenship puts men of fighting age at risk of mobilization into the Russian army — up to 60,000 Ukrainians in the occupied territories are believed to have been already forced to take up arms against their own country, mostly in the separatist-held areas of Donetsk and Luhansk regions. These areas found themselves in legal limbo between Russian recognition on the eve of the invasion and subsequent annexation.41Main Intelligence Directorate of the Ministry of Defense of Ukraine, ‘Russia forcibly mobilizes about 60,000 people in temporarily occupied territories of Ukraine,’ 31 July 2023

Noting a lack of adequate reporting, ACLED records an over 90% decrease in the incidents of civilian abductions in the second year of the invasion. Over a quarter of them were recorded in the Zaporizhia region, including the deportation of about 300 civilians from areas around Enerhodar in early May 2023 and the detention of at least five ZNPP employees. Furthermore, Russian forces and the Russian occupation government deported hundreds of Ukrainian children, including toddlers, to Crimea and Russia, ostensibly to summer camps and rehabilitation centers where they are subjected to indoctrination and put up for covert adoption.42Mari Saito et al., ‘How Russian officials and their collaborators spirit away Ukraine’s children,’ Reuters, 11 January 2024 The practice continued despite an international arrest warrant issued for President Putin and his Children’s Rights Commissioner Maria Lvova-Belova in March. Since the beginning of the invasion, Russian forces and the occupation government have deported up to 20,000 Ukrainian children under various duty-of-care pretexts, including to Belarus.43Amy Mackinnon, ‘Belarus Is Abducting Ukrainian Children in Plain Sight,’ Foreign Policy, 11 August 2023 Only about 500 children were returned to Ukraine.44Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty – Russian Service and Current Time, ‘Ukrainian Rights Commissioner Says Only 517 Children Out Of Almost 20,000 Taken By Russia Have Been Returned,’ 15 January 2024 The retrievals are complicated by the Russian demand that parents or guardians arrive in person, with the sole route available to them being through a single Moscow airport, where they undergo harsh interrogation, also known as ‘filtration.’45Evgeny Legalov and Sergey Dobrynin, ‘Mattresses in Sheremetevo. Ukrainians await ‘filtration’ for days,’ Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty – Russian Service, 9 November 2023

Similarly, ACLED records significantly fewer looting events than in the first year of the invasion. As a rule, they occur in the occupied parts of the Kherson and Zaporizhia regions (which are less affected by destruction) and include instances of seizure of businesses, equipment, residences, and land plots. Forced transfers of properties also occur under the threat of prosecution and torture for alleged pro-Ukrainian stances if lawful owners remained in occupied areas.46Polina Uzhvak, Rina Nikolaeva, ‘You will die and no one will find out,’ Important Stories, 3 October 2023 Russian forces and the occupation government have also looted Ukrainian cultural heritage, with about 110,000 artifacts removed from the occupied parts of Ukraine to museums in Russia.47Teksty, ‘The stolen treasures,’ 19 September 2023

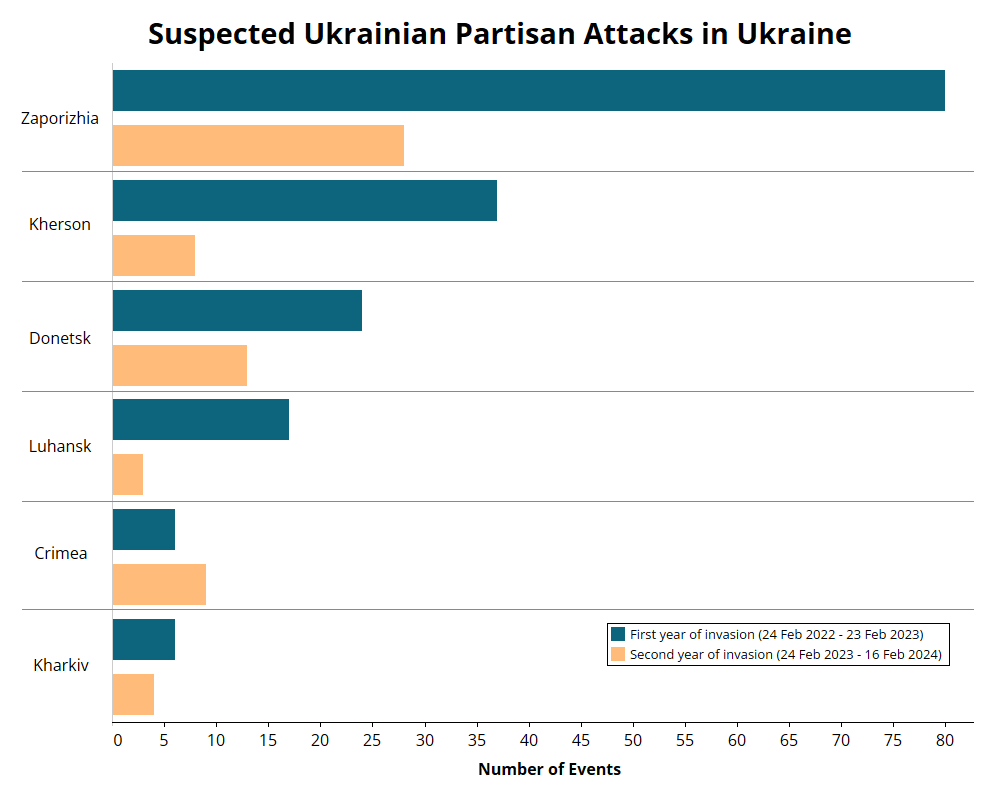

Intensifying oppression did not completely dissuade Ukrainian partisan attacks. The number of incidents attributed to local resistance groups more than halved compared with the first year of the invasion, largely clustering in southern Ukraine and especially in the Zaporizhia region (see graph below). There were also at least three high-profile assassination attempts in the Luhansk region. The preferred method remained the same — the detonation of explosives, usually planted near vehicles, properties, and railway tracks. Partisan groups appeared to have shifted focus from Russian occupation officials and local collaborators to armed personnel as the number of civilian targeting events saw a sharper decline. In one of the most controversial incidents, Russian forces killed two teenagers in Berdiansk, Zaporizhia, in a claimed shootout in late June. Earlier, Russian forces detained the two boys on suspicion of carrying out partisan attacks, prompting international calls for their release.48Media Initiative for Human Rights, ‘European Parliament adopts resolution demanding to stop the persecution of Ukrainian teenagers Tihran Ohannisian and Mykyta Khanhanov,’ 15 June 2023 Russia refuses to hand over the victims’ bodies in a probable cover-up of an extrajudicial execution.49Halya Coynash, ‘Russia refuses to return bodies of Ukrainian teenagers it killed in occupied Berdiansk,’ Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group, 29 December 2023

Outlook

Entering its third year, the war in Ukraine is proving more of a marathon than a sprint. Capitalizing on the disarray caused by the failed Ukrainian counter-offensive both within and outside Ukraine, Russia appears to be doubling down on its assault on the country. In the coming months, it will likely attempt to occupy as much territory as possible, even though rendering it barely inhabitable in the process. Despite a rhetorical willingness to negotiate peace provided that it is allowed to preserve the occupied areas,50Guy Faulconbridge and Darya Korsunskaya, ‘Exclusive: Putin’s suggestion of Ukraine ceasefire rejected by United States, sources say,’ Reuters, 14 February 2024 Russia’s apparent end game is to abolish Ukraine’s statehood, not only to partition the country.51Nataliya Bugayova, Kateryna Stepanenko, and Frederick W. Kagan, ‘Weakness is Lethal: Why Putin Invaded Ukraine and How the War Must End,’ Institute for the Study of War, 1 October 2023 The spillover of the war into Russia’s own internationally recognized territory, however asymmetrical, only reinforces the narrative peddled by Russia’s leadership and its propaganda that Russia is engaged in an existential proxy war with “the collective West,”52TASS, ‘Special military operation to continue until achieving all goals — Kremlin,’ 14 February 2024 rather than embroiled in an attempt to conquer a sovereign nation.53The Economist, ‘Vladimir Putin is dragging the world back to a bloodier time,’ 24 December 2023 Short-term growth spurred by high oil prices and the military industry output, delayed and blunted effects of sanctions, and generous payouts to the wounded and the next of kin may be convincing both Russia’s leaders and some among the public that waging war makes economic sense. Shunned by the G7 countries, Russia turned to the Global South for markets and to fellow pariah states such as Iran and North Korea for weapons and ammunition, further undermining rules-based order.

Outgunned, overwhelmed, and exhausted, Ukraine is facing the prospect of another year of fierce fighting. It is perilously dependent on external aid and supplies, which may dwindle if nativist politicians gain more clout in the upcoming wave of elections in Europe and the United States. Civilians in areas under Ukrainian government control will continue to be exposed to injury or death, with greater risk along the frontline, but also no guarantee of safety even in the westernmost regions as Russia methodically directs its drones and missiles not only toward military or dual-purpose targets but also to civilian infrastructure and production centers. As Ukraine has become the most mine-contaminated country on record,54Daniel Boffey, ‘You don’t survive that’: Ukraine sappers dice with death to clear Russian mines,’ Guardian, 13 August 2023 a protracted war in which cluster munitions are par for the course will exact an immediate and long-term toll on civilians, especially in rural areas in a country where agriculture is an important sector of the economy. Continuing hostilities may keep the over 6 million refugees out of the country, complicating returns in the long run.55United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, ‘Ukraine Refugee Situation,’ accessed on 8 February 2024

Yet the fate of the about 5 million Ukrainians living under Russia’s occupation is unenviable in multiple respects. Subjected to harsh societal controls as Russia is cementing its rule through forced naturalization, displacement, and colonial-style resettlement, the residents of the occupied areas are becoming increasingly isolated from the rest of Ukraine and the outside world. The longer it takes for Ukraine to liberate its territory, the fewer the chances that the experiences of civilians will ever become known — as Russian forces and the occupation government are likely expunging evidence of mistreatment of civilians.

Visuals produced by Ana Marco.