Q&A with

Deborah Alois

ACLED Pacific Region Researcher

On Sunday, 18 February, intertribal violence in the remote Highlands of Papua New Guinea resulted in the death of at least 49 people. This is the worst death toll in an escalating cycle of violence and political unrest in the past year. In this Q&A, Deborah Alois, ACLED’s Pacific region researcher based in the capital, Port Moresby, suggests that the trend will likely persist.

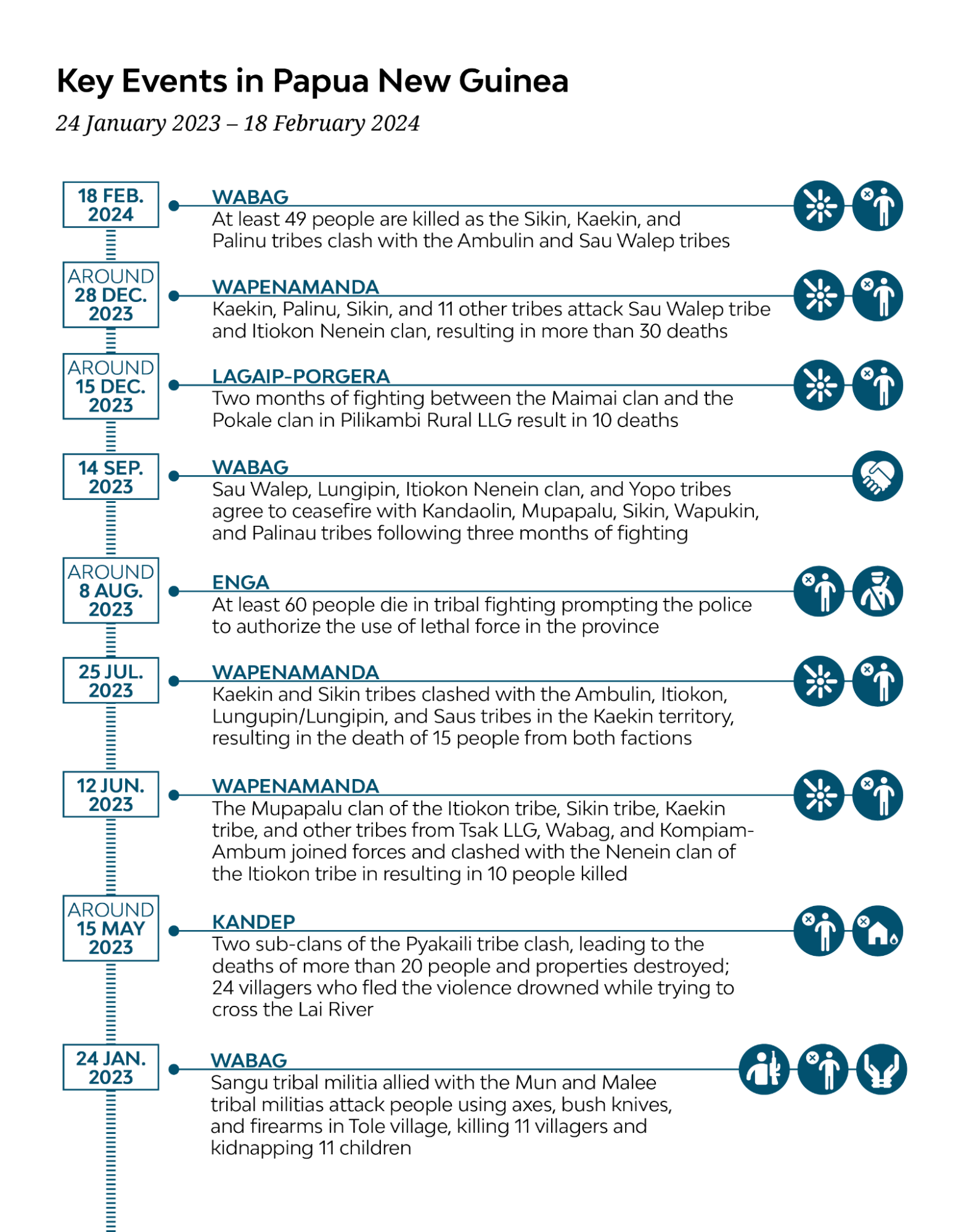

See below for a timeline of key events.

What more information has reached you in Port Moresby about last week’s killings in Enga?

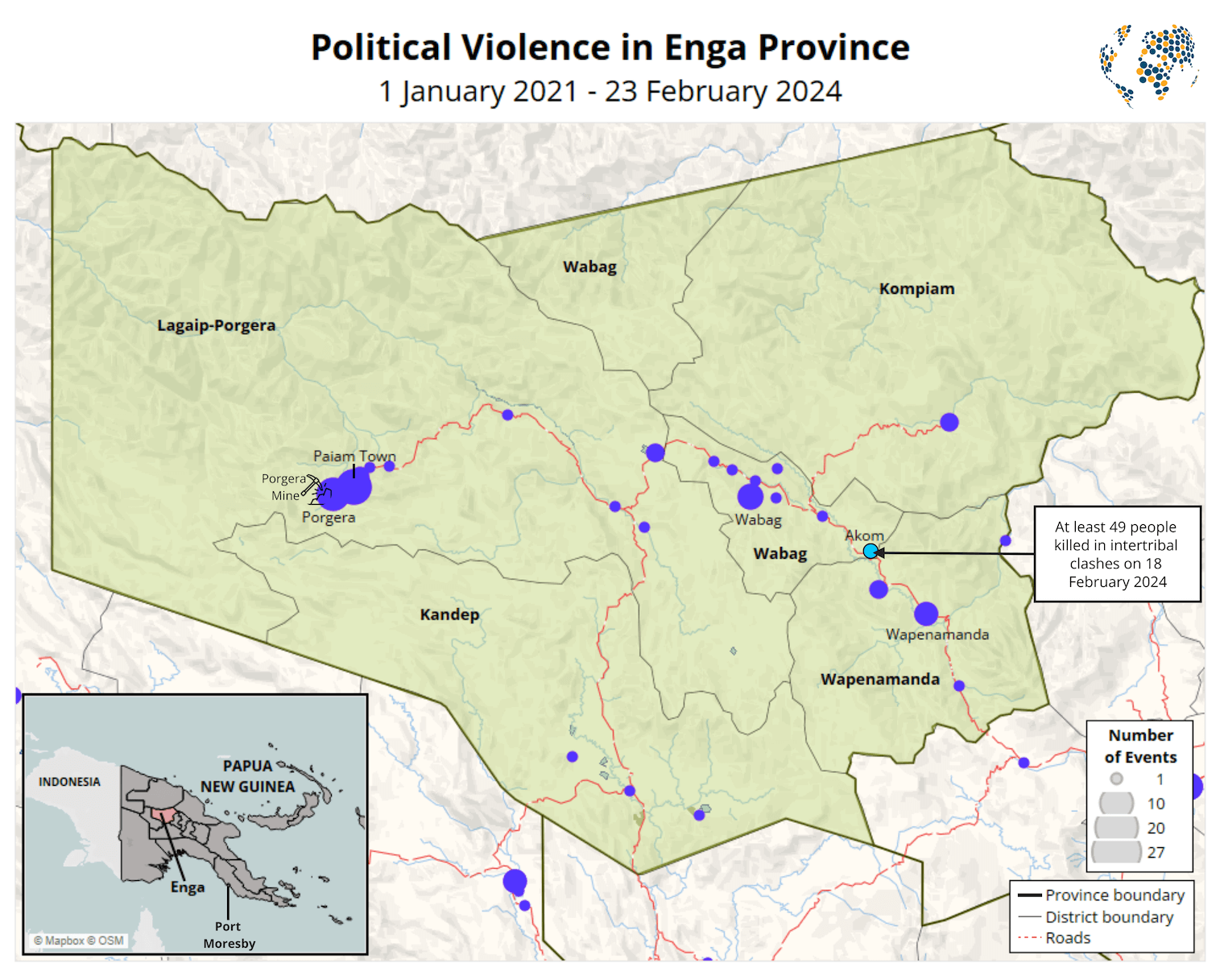

These killings are the worst we’ve had in recent years in Enga province, and maybe in the whole of the Highlands region. However, much of the information from this remote mountainous central area of Papua New Guinea’s main island area remains unclear; mainly due to inadequate fact-checking — so we need to take care in sifting through it. But the names of the tribes involved are well known from previous incidents.

The authorities say at least 49 people were killed on 18 February, when the Sikin, Kaekin, and Palinu tribes clashed with the Ambulin and Sau Walep tribes. The violence erupted after the Ambulin tribe heard about a potential attack planned on them and ambushed the other tribes in the village of Akom, which is on the border of Wabag and Wapenamanda districts. The fight reportedly involved up to 17 tribes, including outside-hired gunmen. The total number of dead is still unknown, and the authorities are struggling to retrieve the bodies, due to difficult terrain and continued tension. Wapenamanda remains a high-security risk area.

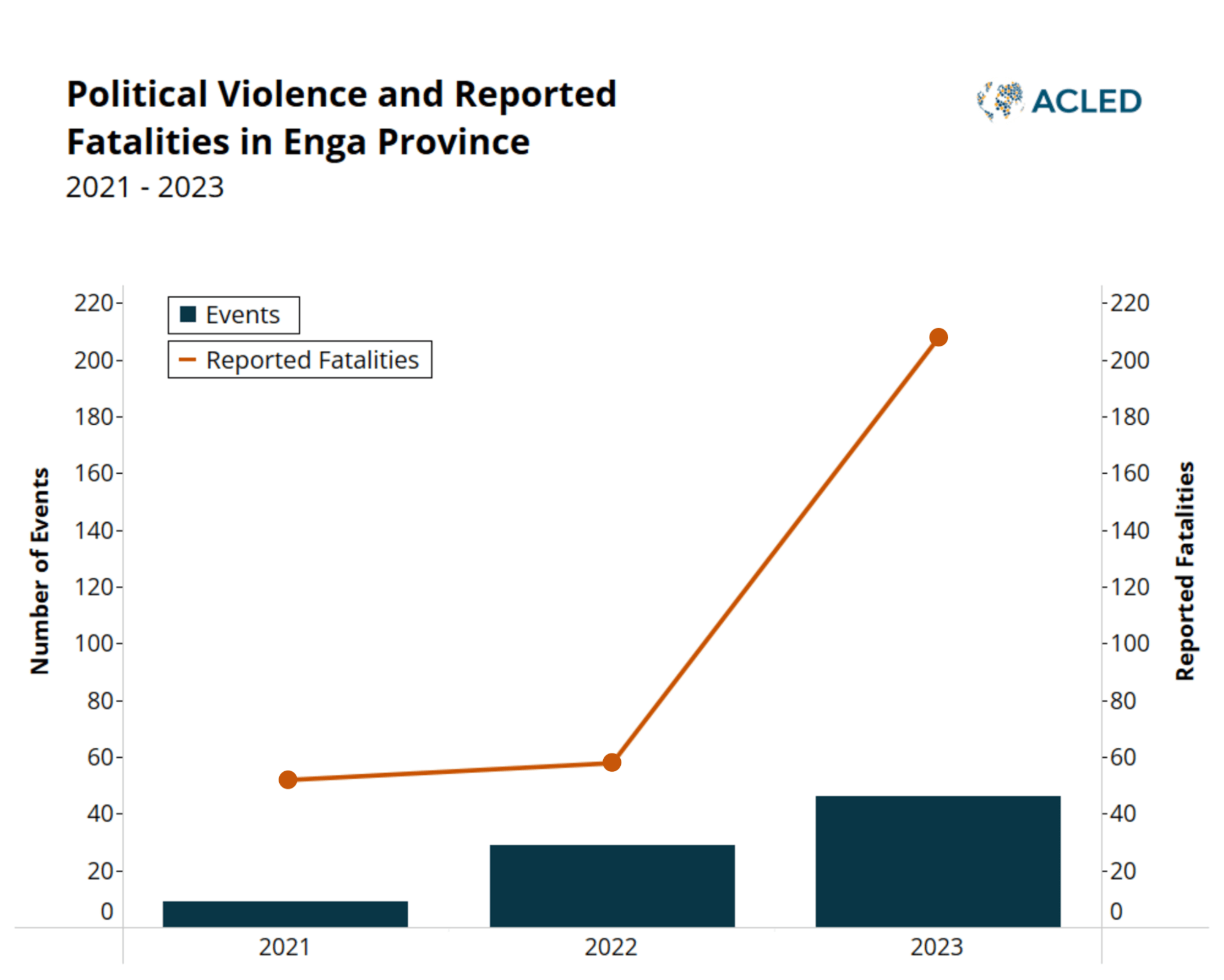

It’s not just that this was the worst massacre on record in Papua New Guinea. What’s even more worrying is that it’s the latest spike in a rising trend of violence. For instance, ACLED’s Early Warning Dashboard shows that we are now averaging nearly six violent or protest events each week, up from just over three a year ago. Our Conflict Alert System (CAST) predicts that violent events will continue, that is, battles or violence targeting civilians. Of course, there are also time periods that are quite peaceful. Violence in PNG is mostly spontaneous and reactionary, which makes prediction difficult. The Sikin and Kaekin, tribes — some of whom sustained heavy casualties in the fighting — said in a press conference they were ready to lay down arms and appealed to their rivals to accept a government-mediated peace deal.1Papua New Guinea Post Courier, ’Fighting tribes in Enga call for peace,’ 28 February 2024 However, it’s safe to assume this rising trend of violence is likely to persist.

Does anyone know what caused the massacre in Enga?

It is unclear what triggered the killings this time. Some dynamics in Enga are decades old, like land disputes and tribal alliances. Some forms of violence are spontaneous acts, such as theft or murder. Tribal fights were a traditional method of conflict resolution. However, this modern day warfare does not appear to be about conflict resolution, but rather a play for power. You see, there is a deep connection between our identity and our land: Take away our land, and you have rendered us nameless. What we’ve observed in Enga today is that warring tribes fight to take ownership of their enemy’s land by any means necessary. Defeated tribes then either regroup or create new alliances to retaliate. It’s a persistent cycle of violence.

There are several other factors too. One is weaponry. The authorities said that the tribes had access to M16s, AR15s, self-loading rifles, and pump-action shotguns.2Tim Swanston, ‘How the funnelling of high-powered weapons into Papua New Guinea is making tribal violence deadlier,’ ABC News (Australia), 19 February 2024 When people were only using spears and arrows in the old days, casualties were probably far fewer, although some academics say we just don’t know. Then there is the rise in hired gunmen rumored to be financed by elite businessmen with familial links to the warring tribes. On top of that is the increase in social media and smartphone usage. This speeds up the spreading of information, rumors, and calls to action.

Finally, the government struggles to maintain law and order in the area. It’s hard to say how many people live in Papua New Guinea — let’s say it’s 11 million people — but there are only about 6,000 members of the constabulary. This makes the country’s police-to-population ratio one officer for every 1,845 people, which is less than one-fourth of the United Nations recommendation of one for every 450 people.3Rebecca Kuku, ‘Boost for police manpower,’ The National, 28 March 2023; Sean Jacob, ‘Putting PNG’s police shortage on the agenda,’ Griffith Asia Institute. 10 August 2023 For instance, in Enga province, there are approximately 300,000 people and only 200 policemen.4Natalie Whiting and Hilda Wayne, ‘Tribal fighting over PNG election leaves dozens dead and villages deserted,’ABC News (Australia), 2 May 2023 The problem is made worse by the inaccessible geography, the way most police are posted in towns or district stations, while most of the Engan population are in the rural areas where there is little to no police presence.

In response to the latest killings in Enga, the authorities have deployed additional security teams to the area. The national parliament in Port Moresby is trying to pass new domestic terrorism legislation, which will give the authorities more power to counter people who carry out such acts. But resources are limited, and it’s unclear whether this can break the cycles of violence.

Is there any sign that the killings in Enga are linked to national political problems in Papua New Guinea?

There’s no specific link I know of between the Enga massacre and national politics, or with the rioting and looting that killed 25 people in Papua New Guinea on 10 and 11 January. We do see repeated feuding inside Port Moresby between various tribal groups that settle here, but that is probably not related to anything that’s happening in the provinces. On the other hand, when somebody has been attacked in a province, we’ve seen revenge taken on tribal members living in Port Moresby.

Some people are speculating that the Enga killings serve to distract the population from the growing political difficulties of Prime Minister James Marape and his government. There are also some rumors that elite businessmen in Port Moresby were involved in the recent violence and supplied the tribes with arms and ammunition. The authorities do say they are trying to bring any elites involved in supplying weapons to justice.

But while I doubt there’s a direct connection between the Enga massacre and problems in the rest of the country. In recent times, there have been a lot of national, political, and governance issues that have exacerbated the security situation in general.

How did the January rioting affect you in Port Moresby?

It was a really tense time; many were trapped at work or in public places when rioters took over the streets that day. Like most people, I was watching the events unfold through live videos and real-time updates on social media. The rioters were men, women, even children. Demonstrators overran the gate of the parliament building and torched a car outside the compound. In their social media posts, looters openly shared their spoils and encouraged others to loot as well. It’s the first time we’ve seen social media used for something like this in PNG. Within a few hours, the news of the Port Moresby riots spread across the country. As a result, we saw copycat riots erupt in other urban centers the next day.

The factor behind the rioting that comes up a lot is unemployment, which affects a lot of people in urban areas, especially Port Moresby. For example, people flee from the Highlands region where there is high tribal violence and they seek refuge and opportunities here. However, they’re not as skilled as they would need to be to secure the formal jobs that are currently available. So they resort to the informal economy, things like street vending. These are the people who are liable to loot when law and order breaks down.

The January riots all started after incorrect reports spread that public sector paychecks were going to be reduced by up to 50%. Police and other public sector employees went on strike. The government blamed the cut on a computer glitch and promised to fix the error in February, which it has done. We’ve now also learned that the missing amounts were nowhere near 50% of salaries, being around 40 to 60 PNG kina, which is equivalent to around 10-15 US dollars. Prime Minister Marape, ordered a state of emergency for 14 days. The controller of the state of emergency, Acting Police Commissioner Donald Yamasombi, instructed security personnel to search and retrieve looted goods from private homes. Things calmed down once the security forces resumed their duties. Life in Port Moresby has now returned to normal, however, we are now experiencing notable increases in the cost of everyday goods as businesses attempt to recover in the aftermath.

Has there been any political fallout from the January riots and the February massacre?

The violence is both causing and feeding high-level political tension and confusion. Prime Minister Marape faces calls for his resignation both from the opposition, which says his response was weak and lacked leadership, and also from the coalition allies of his ruling Pangu Party. The prime minister then reshuffled his cabinet on 15 January, appointing six new ministers, including a newly established Ministry for Administrative Services overseeing census, elections, and constitutional matters.⁴ At least seven allied members of parliament have resigned from the government after the riots, blaming Marape for the unrest and saying that they have lost confidence in him. Those resigning included former Minister for Energy and Petroleum Kerenga Kua, an opposition member of the cabinet who felt disrespected after he lost the government’s critical petroleum portfolio.5The National, ‘Kua resigns,’ 29 January 2024

Having suspended the police commissioner and the secretary for personnel management after the January riots, Marape has now reinstated them. The secretaries for treasury and finance, however, remain suspended. Marape has accused members of the political establishment itself of having played a role in the January riots.⁵

On 9 February, we also reached the end of an 18-month ban on votes of no confidence in the government after the last election in August 2022. The government has so far fended off calls for the vote to be held, prompting the opposition to warn6Tim Swanston, ‘Marape fends off no confidence vote amid violence surge,’ ABC News (Australia) -YouTube, 22 February 2024 that this will only push popular anger onto the street.

Internationally, the US, China, and even France have been courting Papua New Guinea as a key state in the Pacific region. Does this have any impact on the situation?

Yes, we’ve had a lot of visits, but the dynamics in the violence are all domestic, at least the ones I’m aware of. Triggers are on a broad spectrum: specific isolated events such as theft or murder; long-standing conflicts over land; and a routine practice of resorting to violence to address interpersonal disputes.

In fact, Australia has offered to send assistance for security. Outside powers are worried about our security and stability. Their interests — whether concerning geopolitical competition or mining concessions — mean that there’s been a lot of attention paid to getting us back to a stable state.

Regrettably, unless conditions improve, it’s likely that we’ll see further instances of violence in the future. Conflicts among people will persist, leading to more casualties, and the situation may escalate. This has unfortunately become the prevailing norm in my country. There needs to be a structural change to address a wide variety of issues, but above all, we need to address the normalization of violence.

Deborah Alois was in conversation with Laura Sorica, ACLED’s Asia-Pacific Research Manager, and Hugh Pope, ACLED’s Chief of External Affairs.