Situation Update | March 2024

Sudan: Escalating Conflict in Khartoum and Attacks on Civilians in al-Jazirah and South Kordofan

15 March 2024

Sudan at a Glance: 10 February-8 March 2024

VITAL TRENDS

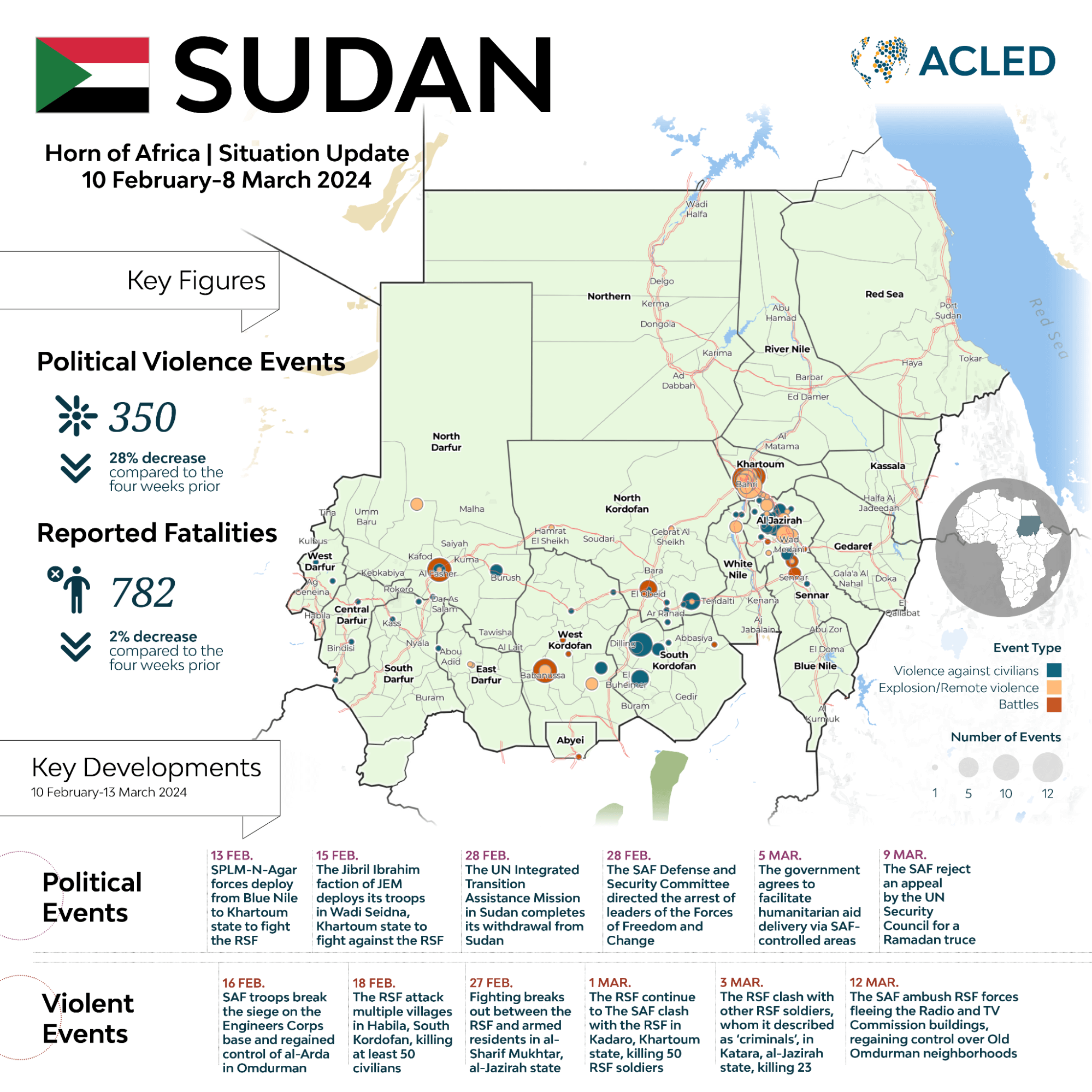

- Since fighting first broke out between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) on 15 April, ACLED records over 5,170 events of political violence and more than 14,790 reported fatalities in Sudan.

- From 10 February to 8 March 2024, ACLED records over 350 political violence events and 782 reported fatalities.

- Most political violence was recorded in Khartoum state during the reporting period, with over 157 events and 238 reported fatalities.

- The most common event type was battles, with 140 recorded, followed by violence against civilians, with nearly 120 events. Compared to the previous four weeks, ACLED records a 30% decrease in battles and an 89% increase in violence against civilians.

Escalating Conflict in Khartoum and Attacks on Civilians in al-Jazirah and South Kordofan

As the ongoing conflict between the SAF and the RSF nears the one-year mark, the SAF has begun to reclaim control over territory in the capital Khartoum after adopting offensive tactics and capitalizing on the scattering of RSF forces in other states. Advances by the SAF in Omdurman since January led to the linking of its forces in the north and south of the city. On 16 February, the SAF successfully broke the siege on its troops in the Engineers Corps base after weeks of what seemed to be an offensive based on attrition, whereby its troops engaged in recurrent infantry skirmishes, artillery shelling, and drone assaults.1The SAF is reportedly using Iranian-made drones for its offensive on Khartoum. See Africa Defense Forum, ‘SAF’s Use of Iranian Drones Threatens to Destabilize Region,’ 13 February 2024 The SAF’s offensive shift has altered the dynamics of the battle in the metropolitan area of Khartoum. Clashes have also raged in al-Jazirah state, southeast of the capital city, as the RSF and the SAF locked horns along the borders with neighboring Gedaref, Sennar, and White Nile states. Since SAF’s withdrawal from Wad Madani city in December, the RSF has initiated a coordinated campaign of violence targeting civilians in al-Jazirah — though the military strategy behind this move remains unclear.

In separate developments, the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-North (SPLM-N) led by Abdelaziz al-Hilu has seized control of Habila in South Kordofan, prompting a violent retaliation from the RSF against the ethnic Nuba population in surrounding villages. The Nuba pledged their support to the SAF or al-Hilu’s faction of SPLM-N.

Besieged to Besieger: The Siege Reversed in Khartoum

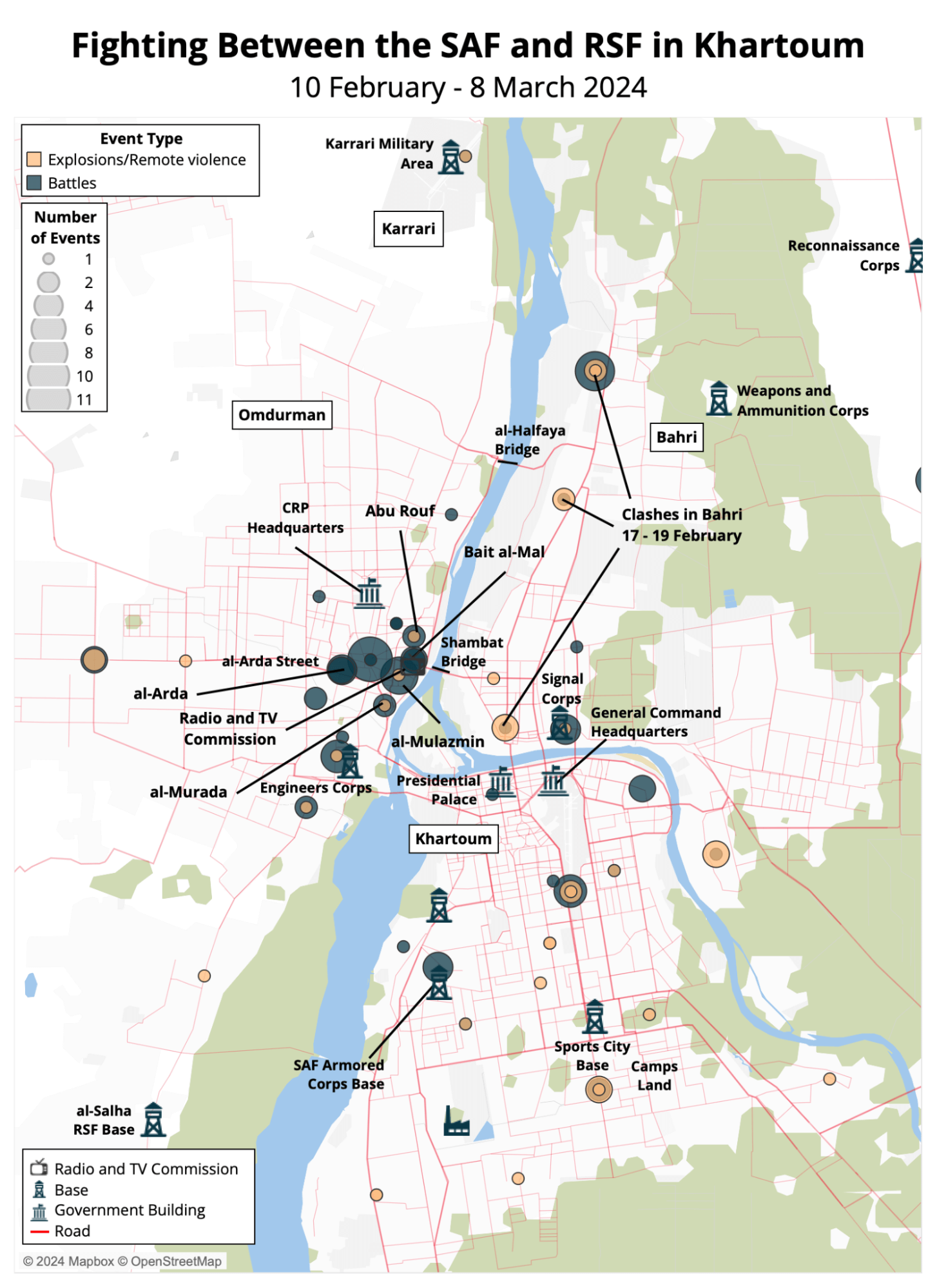

The break of the siege on the SAF-controlled Engineers Corps military base in south Omdurman after 10 months of siege by the RSF marked a turning point in the battle of Khartoum. The previously besieged SAF troops have since led an offensive and tight siege on the last RSF bastion in the Radio and Television Commission buildings located in east Omdurman, and kept advancing in other areas in Omdurman.

The change in fortunes for the SAF comes as part of a new strategic shift from defense to offense that has seen them in Old Omdurman neighborhoods. Prior to the SAF adopting this new offensive stance, the RSF was capable of withdrawing and dispersing whenever the SAF launched attacks, while the SAF typically opted to retreat to its bases rather than establishing checkpoints to secure regained territory.2Africa Defense Forum, ‘Sudanese Army Aims to Regain Ground, Public Support Against RSF,’ 20 February 2024 The SAF’s new strategy — combined with the deployment of snipers and the establishment of multiple checkpoints in January — has not only prevented the RSF from making new advances in Omdurman, but also seen their losses compounded.

The SAF continues to regain more territory in Omdurman, forcing the RSF troops to the eastern, western, and southern neighborhoods of the city. After the SAF regained control of parts of al-Arda neighborhood in Omdurman, its troops positioned north and south of the city eventually broke the isolation. RSF troops had maintained a presence in certain areas of Old Omdurman, but ultimately retreated to al-Mulazmin from Bait al-Mal, Abu Rouf, and al-Murada between 25 to 29 February.

The SAF continued advancing around its bases across Khartoum’s metropolitan area. To divert the RSF’s attention and resources away from Omdurman, the SAF targeted RSF positions in Bahri, where it struck fuel tanks coming from the al-Gaili Petroleum Refinery before clashing with RSF troops between 17 and 19 February (see map below). During those days, the SAF reportedly inflicted considerable losses on RSF equipment and personnel. The SAF also claimed to have destroyed several RSF vehicles and killed dozens of RSF troops during clashes between 26 and 27 February.3Sudan War Monitor, ‘Chad instability threatens Darfur refugees,’ 29 February 2024

The besieged RSF troops find themselves with limited means of escape. The Nile river was their only viable route, from which they received sporadic boat deliveries of weapons from the opposite side of the Nile river to sustain military operations.4Radio Dabanga ,’Missiles kill seven in ongoing Sudan capital battles, army regains control of Abrof,’ 26 February 2024 The RSF — which seems to be focused on consolidating control over Kordofan, al-Jazirah, and Darfur — faces the challenge of defending its positions in Old Omdurman, where its forces were isolated and surrounded by the SAF. Meanwhile, the SAF has kept advancing from north, west, and south towards al-Mulazmin neighborhood and imposed a tight multi-front siege which gradually reached the vicinity of Radio and TV Commission buildings. The frequent clashes, artillery shelling, and airstrikes eventually wore down the RSF forces. Despite its tactical advantage, the SAF has refrained from launching a full-scale invasion of the Radio and Television Commission buildings, one of the RSF’s last strongholds in Omdurman, instead the SAF waited until the RSF forces attempted to escape west on 12 March. Concurrently, RSF forces in the west of al-Arda Street attacked SAF forces to create a passage through the siege. However, the SAF successfully ambushed the escaping forces in al-Arda Street, where they were seemingly blocked by dirt barriers and subjected to heavy drone strikes, resulting in the destruction and elimination of all RSF forces.5Sudan Tribune, ‘Sudanese army encircles RSF in Omdurman Radio TV building,’ 25 February 2024; Sudan War Monitor, ‘Sudan paramilitary suffers crushing defeat in Omdurman,’ 12 March 2024.

The ongoing fighting in Bahri suggests that the next phase after breaking the siege on the Engineers Corps base might be linking the SAF troops stationed at the Signal Corps base in the south with those at the Weapons and Ammunition Corps base in north Bahri. This strategic advance aims first to secure control over the Radio and Television Commission buildings and then advance to Bahri, in order to break the siege on the Signal Corps base and the General Command headquarters in Khartoum. As the RSF appears to be gradually collapsing in Khartoum tri-cities, it is now increasingly difficult for them to regain the upper hand in the capital.

Multiple Frontlines and Violent Attacks on Civilians in al-Jazirah

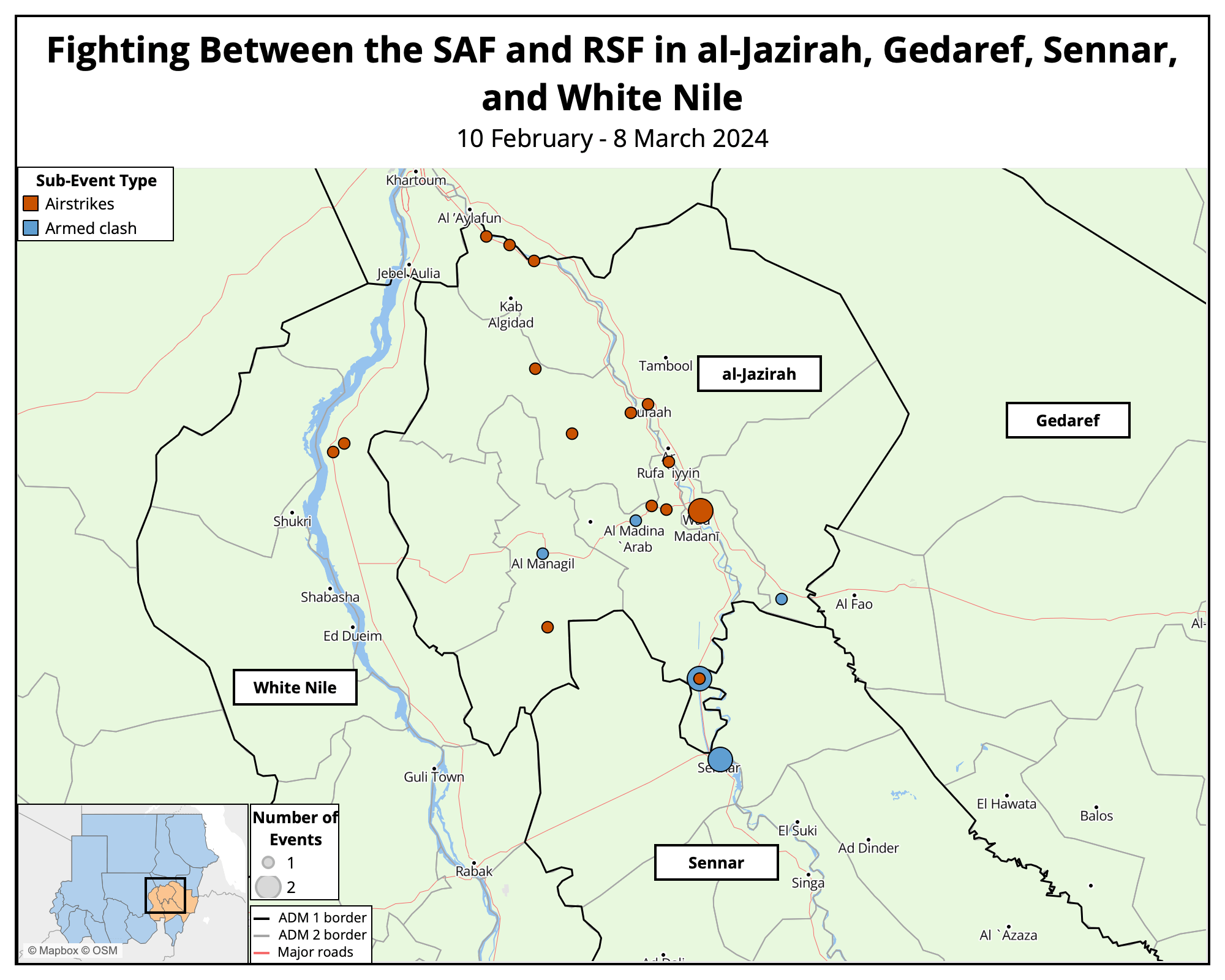

The fall of al-Jazirah to the RSF in December 2023 left the civilian population exposed to RSF atrocities. The SAF’s limited presence in the western areas of al-Jazirah shifted the conflict’s geography from urban areas to peripheral and non-urban regions, with clashes between the SAF and the RSF being concentrated in the border areas of Sennar and Gedaref states. Al-Jazirah state — located in the center of Sudan and surrounded by SAF-controlled Gedaref state to the east, White Nile state to the west, and Sennar state to the south — is one of the conflict hotspots where the RSF aims to divert the SAF’s attention to, rather than advancing toward Khartoum.

On 10 February, the RSF launched a widespread looting campaign and attacked civilians across at least 66 villages within different localities of al-Jazirah. While some local militias made limited attempts to resist this campaign, the RSF swiftly crushed these militias and proceeded to loot their villages.6Darfur 24, ‘Deaths, injuries, and displacement as RSF attack Al-Farijab village in Aljazeera state,’ 16 February 2024 For instance, ACLED records that armed residents clashed with RSF fighters to defend themselves from looting in al-Ferejab and al-Sharif Mukhtar villages. However, the full extent of the situation is yet to be revealed due to the internet outage across Sudan since 6 February. Despite efforts by RSF military police to control the violence perpetrated against civilians, the RSF appears to be struggling to rein in its soldiers. The ongoing violence against civilians and looting by RSF troops do not seem to have any clear political or military objectives as the RSF does not face any resistance in al-Jazirah. Moreover, the RSF’s military goals in al-Jazirah have been achieved since the fall of the state in December and it does not seem like the RSF aims to create an alternative supply route from Darfur via Kordofan through al-Jazirah for military supplies and reinforcements, because its geography does not provide this access. Additionally, and in contrast to Arab and non-Arab tensions in Darfur and Kordofan, al-Jazirah state has diverse communities comprising various ethnic groups from across Sudan, and therefore, the state lacks ethnic tensions as a contributing factor to conflict.

Additionally, armed clashes during the reported period suggest an attempt by the SAF to regain control over Wad Madani, the capital city of al-Jazirah, by mobilizing forces in nearby states. At the same time, the RSF is seeking to extend its areas of control east, south, and west of al-Jazirah, with the aim of moving across state borders. SAF airstrikes have been targeting RSF positions in al-Jazirah since mid-February, but during the reporting period, armed clashes broke out in at least three areas of the state: on the eastern border with Gadaref state, on the southern border with Sennar, and on the western border with White Nile (see map below). On the eastern frontline, RSF attacks targeted SAF checkpoints in al-Khayari area in Gedaref state. On the southern frontline near the border with Sennar state, the RSF repelled an attack launched by the SAF-backed Malik Agar faction of the SPLM-N on 5 March. The SPLM-N faction led by Agar, which supported the SAF since the beginning of the conflict in April, began moving its forces from Blue Nile state toward Wad Madani in mid-February.7Sudan War Monitor, ‘4th Infantry to move north toward Wad Madani,’ 26 January 2024

In the western frontline, the RSF mobilized its forces from villages in Janub al-Jazirah locality in preparation to attack the SAF in al-Manaqil. On 4 March, the RSF advanced and controlled al-Madina Arab village east of al-Manaqil, while the SAF troops withdrew to Wad Rabia village. However, the final situation remained unclear at the time of writing, due to the ongoing clashes.

Relentless Contest with Multilayer Complexity in South Kordofan

In South Kordofan, ongoing violence between the SAF and the RSF is linked to the complex networks of alliances between the Sudanese militaries, rebel groups, and local clans. The SAF, RSF, and al-Hilu faction of SPLM-N — the three main armed groups operating in the region — are attempting to consolidate and expand territorial control. This control has fluctuated since April 2023 with the contest between the SAF, SPLM-N al-Hilu, and the RSF, but also historically between the SAF and the SPLM-N since at least 2012. Most recently, the al-Hilu faction of the SPLM-N captured Habila city from the RSF on 10 February. The RSF had previously overtaken the city in December 2023.

In a form of retribution against the local population, the RSF reportedly killed over 70 people from the Nuba ethnic group near Habila between 9 and 12 February, forcing approximately 40,000 residents to leave their homes.8International Service for Human Rights, ‘Civil society demands immediate intervention and thorough investigation in South Kordofan, Sudan,’ 1 March 2024 Members of the Nuba ethnic group historically have been recruited by both the SAF and the SPLM-N-al-Hilu to fight each other.9Sudan War Monitor ,’SPLM-N and Popular Defense Forces field commanders meet in South Kordofan,’ 13 October 2023 After the fall of Habila city to the RSF in late December, the al-Hilu faction of the SPLM-N intervened in collaboration with the SAF to defend the Nuba people in Dilling against RSF attacks.10Sudan War Monitor, ‘Fighting rages in Dilling after RSF attack,’ 10 January 2024 The al-Hilu faction has controlled some parts of South Kordofan since 2012. After the outbreak of the conflict in April 2023, it expanded its control in South Kordofan and clashed with the SAF in other areas of South Kordofan.

The recurring pattern of rebel groups intervening to protect civilians from attacks by the RSF has had severe repercussions for the most vulnerable people. For example, in West Darfur, the Sudanese Alliance Forces, under the leadership of former governor Khamis Abkar, intervened between April and June 2023, to defend the Masalit ethnic group. However, this intervention resulted in a series of retaliatory campaigns by the RSF and allied Arab militias against the Masalit, including ethnic cleansing and forced displacement.11Maggi Michael and Rayen Mcnell, ‘How Arab fighters carried out a rolling ethnic massacre in Sudan,’ Reuters, 22 September 2023 The SPLM-N-al-Hilu’s intervention to defend the Nuba ethnic groups in South Kordofan raises concerns about a similar scenario unfolding. The involvement of the SPLM-N’s al-Hilu faction could potentially escalate tensions and trigger reprisal actions by the RSF and its allied militias against the Nuba population, akin to the violent events witnessed in West Darfur.