A Decade After Chibok: Assessing Nigeria’s Regional Response to Boko Haram

16 April 2024

Ten years after the Chibok girls kidnapping, Boko Haram continues to be a threat to civilians in Borno state — where 1.8 million civilians have been exposed to the insurgent group’s violence since 2020 — and spread to neighboring Cameroon, Chad, and Niger in the Lake Chad region. This report discusses Boko Haram’s trajectory and the results of Nigeria’s regional response.

On 14 April 2014, Boko Haram abducted more than 250 students, all girls, from their dormitories in Chibok, Borno state.1Michelle Nichols, ‘U.N. Security Council threatens action over girls’ abduction in Nigeria,’ Reuters, 10 May 2014 Despite intensified offensives by the Nigerian military, the movement and its offshoot — the Islamic State of West Africa Province (ISWAP) — have persisted as a significant threat to Nigeria and its neighboring states in the Lake Chad region. The audacious attacks perpetrated by both factions on civilians and security posts, coupled with the adverse effects of their activities on vulnerable populations, underscore their adaptability and resilience in the face of sustained national and regional military campaigns by the Lake Chad Basin Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF) over the past decade.

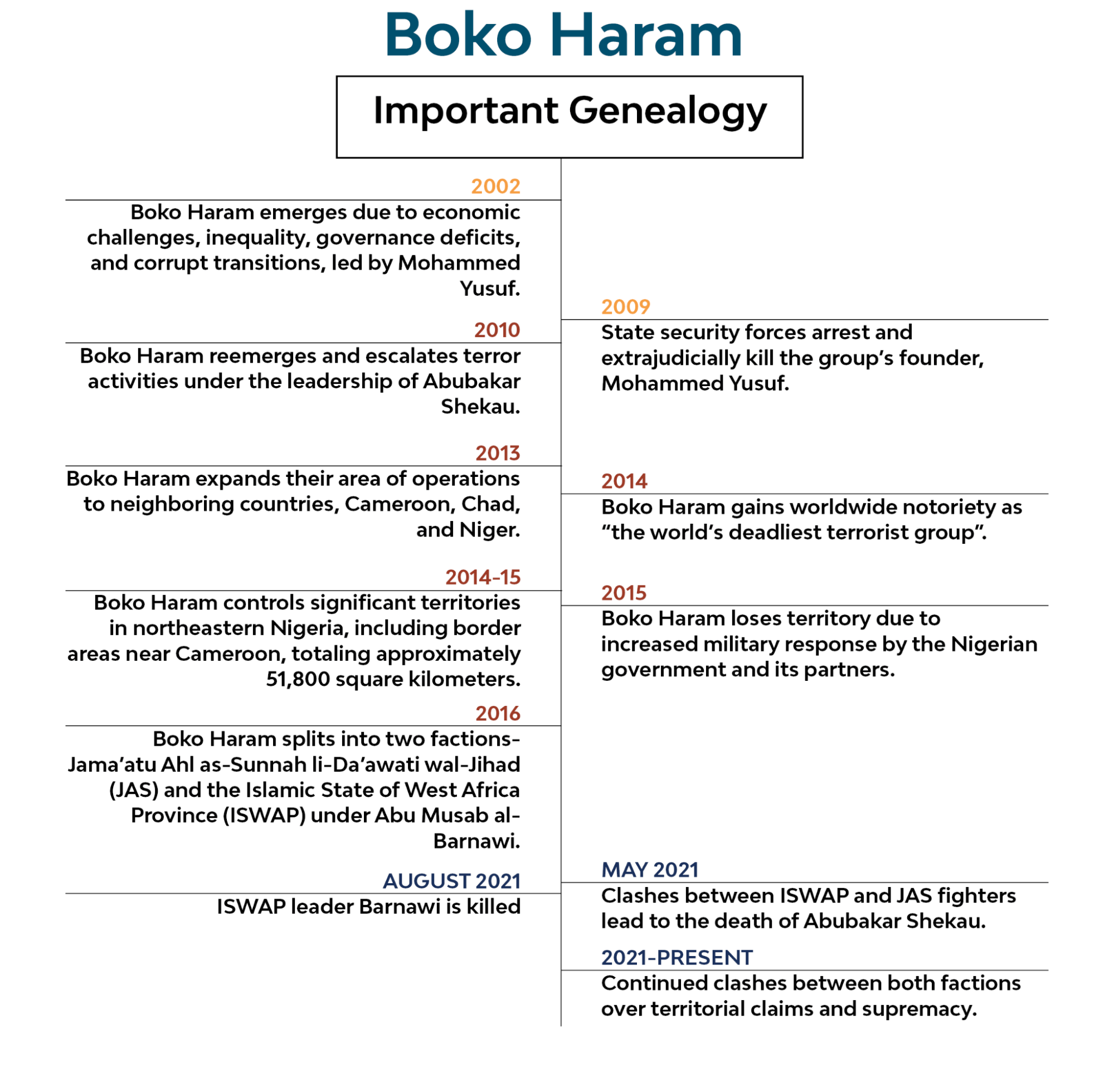

Boko Haram’s Trajectory

Founded in 2002 by Mohammed Yusuf from factional gangs and Islamist sects in the city of Maiduguri, Boko Haram — also known as JAS, short for Jama’atu Ahl as-Sunnah li-Da’awati wal-Jihad — has been notorious for its violent attacks since 2009. Initially labeled the “Nigerian Taliban” by local headlines due to its fundamentalist ideology and adherence to the Salafist theology of the Taliban in Afghanistan,2Audu Bulama Bukarti, ‘The Origins of Boko Haram—And Why It Matters,’ Hudson Institute, 13 January 2020 the movement in its nascent years established its own socio-political institutions: providing welfare, food, and shelter to attract followers, who were mostly refugees from the Lake Chad region and unemployed Nigerian youths.3Daniel E. Agbiboa, ‘Peace at Daggers Drawn? Boko Haram and the State of Emergency in Nigeria,’ Taylor and Francis Online, 20 December 2013, p. 55; Andrew Walker, ‘What Is Boko Haram?,’ United States Institute of Peace, 2012; Daniel Egiegba Agbiboa, ‘No Retreat, No Surrender: Understanding The Religious Terrorism of Boko Haram in Nigeria,’ African Study Monographs, August 2013, p. 72 Although occasional clashes with government troops occurred over specific issues when it failed to respect local ordinances, the bulk of the group’s activities prior to 2009 were peaceful and non-violent. However, following the abduction of the Chibok schoolgirls in 2014, Boko Haram gained worldwide notoriety as “the world’s deadliest terrorist group.”4Institute for Economics and Peace, ‘Global Terrorism Index 2015: Measuring and Understanding the Impact of Terrorism,’ 17 November 2015 Domestic and foreign media coverage of the Chibok kidnappings, along with global outrage calling for the release of the girls with the social media hashtag #BringBackOurGirls, gave the movement the attention it desired.

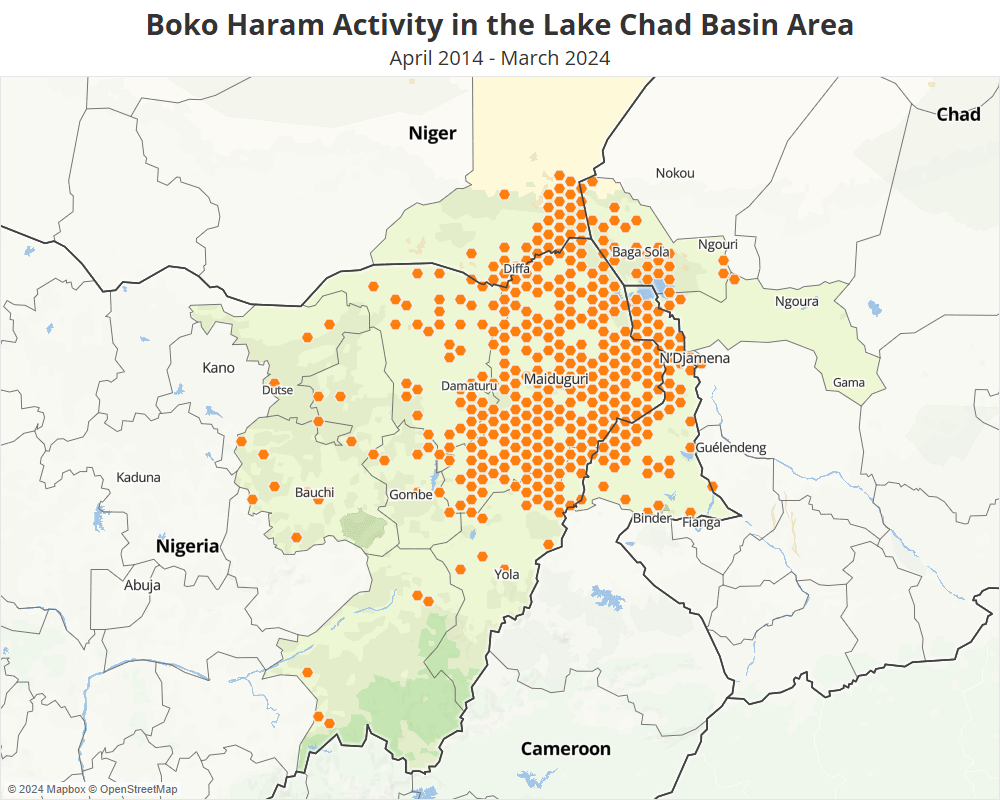

Since then, the group has demonstrated remarkable adaptability, employing various tactics and methods to further its agenda. Notably, the movement has expanded into neighboring countries Cameroon, Chad, and Niger (see map below) and has also demonstrated its capacity to seize and hold towns and villages, particularly during the height of its insurgency between 2014 and 2015. Despite facing significant setbacks following sustained counterterrorism efforts by the Nigerian government and its partners since 2015, Boko Haram continues to control territories in the Lake Chad Basin islands. Additionally, the movement has expanded its operations toward northwest Nigeria, likely in response to ongoing military operations by the MNJTF in northeast Nigeria and neighboring Lake Chad Basin countries. Both factions of the group have continued to rely on hit-and-run tactics that exploit the challenging terrain of northern Nigeria and the surrounding Lake Chad islands to evade military forces, allowing them to maintain a formidable advantage despite concerted counterterrorism efforts.

Recent developments within Boko Haram have further reinforced its threat in the Lake Chad region. Following the death of Abubakar Shekau in May 2021, the ISWAP faction has attempted to absorb JAS fighters and expand into territory formerly controlled by JAS.5International Crisis Group, ‘JAS vs. ISWAP: The War of the Boko Haram Splinters,’ 28 March 2024 This has resulted in frequent clashes over territorial claims and supremacy. ACLED records at least 106 clashes between both factions following Shekau’s death, with significant implications for local communities who have been warned by either group not to collaborate with the other.

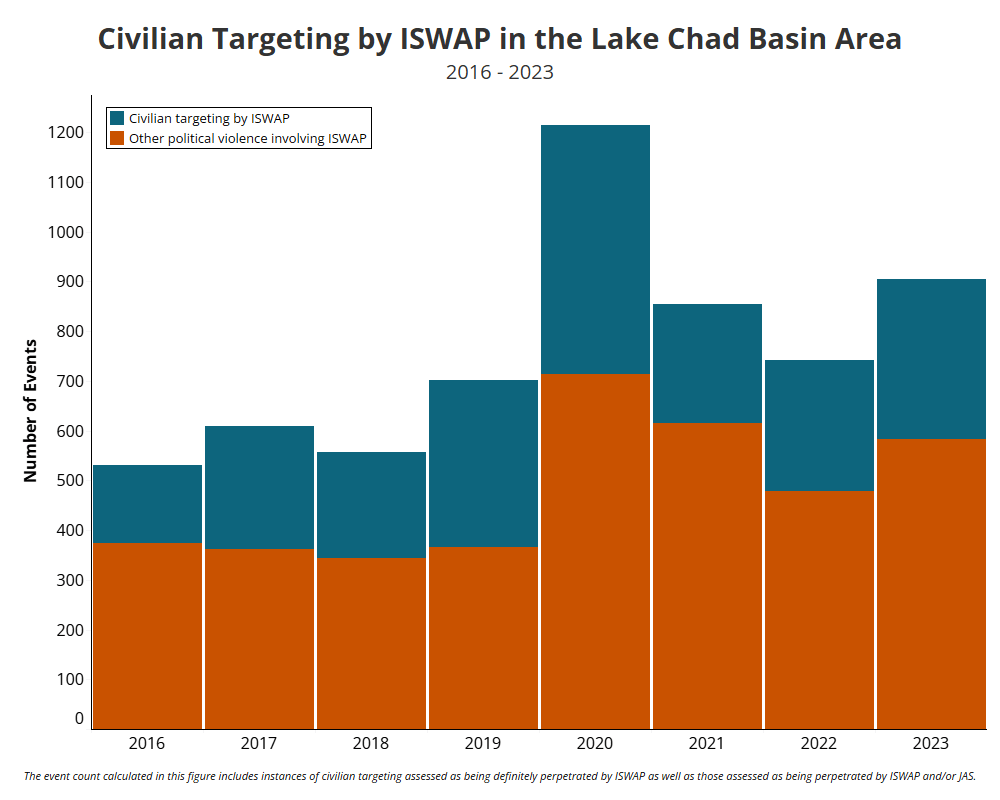

Moreover, ISWAP’s closer alignment with the ‘hearts and minds’ approach toward the civilian population in the Lake Chad area has positioned it as an alternative to the state. This strategy aims to disrupt the civil-military relationship between government security forces and affected communities in the region. The group provides security, services, and livelihoods in communities it controls, allowing it to sustain itself within a competitive ecosystem of contested governance.6Edward Stoddard, ‘Competitive Control? “Hearts and Minds” and the Population Control Strategy of the Islamic State West Africa Province,’ African Security, 29 March 2023 Trends analyzed using ACLED data reveal an almost 50% decrease in violence targeting civilians in 2021 compared to the previous year.7The calculated overall reduction in violence targeting civilians also includes incidents involving events not necessarily attributed to either the JAS or ISWAP faction. These incidents have been coded under events involving Boko Haram and/or ISWAP. While the movement still carries out reprisal attacks on communities perceived to collaborate with state agents, since ISWAP’s official split from Boko Haram in 2016 violence targeting civilians constituted, on average, about 37% of ISWAP’s total recorded activity in the Lake Chad Basin (see graph below).

Nigeria’s Strategy Against Boko Haram: A Regional Approach

In response to the mishandling of the Chibok kidnapping and escalating violence by Boko Haram, in 2015 the Nigerian government launched a more ambitious and coordinated response, collaborating with federal agencies, neighboring countries, and other partner countries to combat Boko Haram.

In particular, the Nigerian government actively sought the cooperation of its neighboring countries, and in 2015, under the continental guidance of the African Union Peace and Security framework, established the Lake Chad Basin Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF) to combat Boko Haram’s cross-border movements.8The MNJTF was established in 1994 by Nigeria as an instrument for the cross-border control of criminal activities in the Lake Chad Basin. It was reactivated and authorized by the African Union in early 2015 to combat the increasing regionalization of Boko Haram. The creation of the MNJTF was underpinned by the recognition by Nigeria, other countries, and the African Union, that the fight against violent extremism requires regional and continental collaboration. The 10,000 strong-force comprising troops from Benin, Cameroon, Chad, Niger, and Nigeria, is primarily funded by the Nigerian government with additional support from strategic partners like the United States and the European Union. The task force aims to establish security in the areas affected by the activities of Boko Haram, facilitate the implementation of stabilization programs, and assist in humanitarian operations and aid delivery.9Multinational Joint Task Force MNJTF, ‘MNJTF Mandate,’ accessed on 15 April 2024

Furthermore, the establishment of the MNJTF in 2015 was a significant step that led to the development of the Lake Chad Basin Regional Strategy for Stabilisation, Recovery, and Resilience in 2018. This strategy was rolled out in 2019 after being validated by the Lake Chad Basin Council of Ministers in August 2018 and endorsed by the African Union Peace and Security Council in December of the same year.10The successful implementation of the strategy was made possible through a multi-level partnership led by the Lake Chad Basin Commission, with support from the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Regional Stabilization Facility for Lake Chad. This partnership facilitated the execution of the Lake Chad Basin Strategy, with the UNDP acting as the custodian of the Secretariat for the Lake Chad Basin Regional Strategy for Stabilization, Recovery, and Resilience. This structure played a pivotal role in leading the implementation of the successful activities mentioned above. See: United Nations Development Programme, ‘Regional Stabilization Facility for the Lake Chad Basin,’ accessed on 15 April 2024

This strategy has been relatively successful. Despite increased activity from Boko Haram and its offshoots, the MNJTF has made considerable progress in degrading the capacity of both ISWAP and JAS. Indeed, the regional task force has emerged as a beacon for best practices of non-military approaches in the region in three major ways.

For one, the establishment of the joint task force’s Civil-Military Cooperation Cell in December 2020 has been pivotal in fostering crucial collaboration between security forces, civilian and humanitarian agencies, and local communities. This initiative has facilitated the deployment of community dialogues and the implementation of several training initiatives for the MNJTF, with a specific focus on protecting civilians, addressing gender-based violence, and complying with International Humanitarian Law and International Human Rights Law.11Chika Charles Aniekwe and Katharine Brooks, ‘Multinational Joint Task Force: Lessons for Comprehensive Regional Approaches to Cross-Border Conflict in Africa,’ Journal of International Peacekeeping, 21 December 2023, pp. 340-42 These training programs have enhanced the attitudes and skills of MNJTF troops, particularly in their ability to employ strategies for civilian protection, thus winning the hearts and minds of local communities. Notably, ACLED data indicates only two instances of violence targeting civilians by the MNJTF since 2020, compared to the 53 instances perpetrated by state security forces of troop-contributing countries, underscoring the task force’s commitment to effectively combating abuses by troops in affected areas. Additionally, community dialogue processes since 2021 have fostered improved community relations, offering valuable insights to the regional force regarding its role in safeguarding affected communities.12Chika Charles Aniekwe and Katharine Brooks, ‘Multinational Joint Task Force: Lessons for Comprehensive Regional Approaches to Cross-Border Conflict in Africa,’ Journal of International Peacekeeping, 21 December 2023, p. 337

Second, the MNJTF’s community-based quick-impact projects have been instrumental in delivering medical supplies and treatment to communities in areas controlled by Boko Haram and/or ISWAP.13Chika Charles Aniekwe and Katharine Brooks, ‘Multinational Joint Task Force: Lessons for Comprehensive Regional Approaches to Cross-Border Conflict in Africa,’ Journal of International Peacekeeping, 21 December 2023, p. 338 These projects are designed to support interactions within communities and have been instrumental in fostering trust-building opportunities for state security forces within these areas. Finally, the regional force’s development of a communication and counter-messaging program, through the creation of radio content challenging violent extremist narratives, has significantly influenced community perceptions toward the MNJTF and other security agencies.14Chika Charles Aniekwe and Katharine Brooks, ‘Multinational Joint Task Force: Lessons for Comprehensive Regional Approaches to Cross-Border Conflict in Africa,’ Journal of International Peacekeeping, 21 December 2023, pp. 338-39

These practices have been disseminated and embraced by the national militaries of MNJTF troop-contributing countries, fostering an environment conducive to cooperative practices that move beyond military-centric interventions in addressing Boko Haram. The weakening of Boko Haram — as indicated by the ability of the Nigerian military in collaboration with the MNJTF to recapture territories previously held by the group,15Adelani Adepegba, ‘How we recovered 20 LGAs from Boko Haram — Olonisakin,’ Nigeria Punch, 30 January 2021 the arrest and killing of Boko Haram’s foot soldiers and key commanders,16Multinational Joint Task Force, ‘Two More Terrorists Commanders Surrender to MNJTF in Lake Chad,’ 26 March 2024; Sahara Reporters, ‘Top Boko Haram Commander, Lieutenant Surrender To Nigerian Military,’ 9 July 2023; Abdulkareem Haruna, ‘Nigerian Military Says Over 14,000 Boko Haram Fighters Have Surrendered So Far,’ Human Angle, 31 July 2022 as well as the surrendering of over 100,000 Boko Haram associates and combatants to state security forces17Chika Charles Aniekwe and Katharine Brooks, ‘Multinational Joint Task Force: Lessons for Comprehensive Regional Approaches to Cross-Border Conflict in Africa,’ Journal of International Peacekeeping, 21 December 2023 — demonstrates the effectiveness of its coordinated regional response in addressing cross-border conflict.

Assessing Nigeria’s Regional Strategy

Nigeria’s regional approach, however, has not prevented Boko Haram from targeting the MNJTF or military troops from contributing countries. Boko Haram fighters have been able to adapt, employing precision attacks and ambushes on MNJTF military patrols and escorts, and shifting their areas of operations when surrounded by state security forces. ACLED records at least 176 armed clashes between the MNJTF and Boko Haram factions between January 2015 and March 2024, along with over two dozen instances of remote explosives detonating and shelling during this same time period.

Operational challenges also emerge for the MNJTF, particularly when national interests and variations in military strategies among participating countries become apparent, especially during critical situations. This was evident in a major operation launched in 2022, Operation Lake Sanity, aimed at flushing out Boko Haram/ISWAP fighters operating along the fringes and islands of Lake Chad, where Chadian forces participated only briefly due to the prioritization of other urgent internal security challenges by the Chadian government.18Chika Charles Aniekwe and Katharine Brooks, ‘Multinational Joint Task Force: Lessons for Comprehensive Regional Approaches to Cross-Border Conflict in Africa,’ Journal of International Peacekeeping, 21 December 2023, p. 343

Furthermore, insufficient financial resources remain a major obstacle. Disputes between military and civilian leadership over the control and use of funds have resulted in delays in disbursements to MNJTF troops, causing interruptions to operations and impacting the relationship between military and civilian stakeholders to some extent. The absence of clear guidelines on the structure of the relationship between the MNJTF military and civilian leadership, as well as the allocation of resources and powers, continues to impede the ability of the MNJTF to plan, execute, and sustain large-scale joint offensive operations without disruptions. For instance, due to funding challenges, it has taken the regional task force two years since the conclusion of Operation Lake Sanity in 2022 to deploy its next large-scale joint offensive, Operation Lake Sanity II, which is scheduled to commence in April 2024.

Additionally, over the past five years, other non-state armed groups in northern Nigeria and other parts of the country have increasingly adopted Boko Haram’s strategy of targeting schools and abducting children. According to ACLED, there have been over 85 abduction events targeting school children since the Chibok kidnapping; the latest kidnapping for ransom involved about 280 school children in Chikun, Kaduna state, on 7 March 2024.19Yakubu Mohammed, ‘Terror in Kuriga: How terrorists kidnapped over 200 students in Nigerian community,’ Premium Times, 10 March 2024 Targeting school children has proven to be an effective tool for negotiating the release of arrested members and transferring large sums of ransom to purchase weapons and fund operations.20Hakeem Onapajo, ‘Why children are prime targets of armed groups in northern Nigeria,’ The Conversation, 15 March 2021 Moreover, groups employing this strategy have garnered local and international attention, showcasing their strength and amplifying their demands on state authorities, despite the government’s stance that it does not view negotiations as a solution to the worsening security conditions in the country.21Priya Sippy, ‘Nigeria’s kidnap crisis: Inside story of a ransom negotiator,’ BBC News, 21 March 2024

The MNJTF and the Future of the Insurgency in the Lake Chad Region

A decade after Boko Haram’s abduction of the Chibok girls, Boko Haram continues to pose a threat to the Nigerian state and wider Lake Chad Basin region. Although the Nigerian government has been able to rescue 20 of the missing girls in the last two years,22Adaobi Tricia Nwaubani, ‘Nigeria’s Chibok girls: Parents of kidnapped children heartbroken – again,’ BBC, 31 March 2024 over 90 girls remain missing, with some feared dead.23Jerry Emmanson, ‘Parents Beg For Release Of 92 Chibok Girls,’ Daily Leadership, June 2023 Global advocacy for the missing schoolgirls is also fading, and parents of the remaining abducted schoolgirls lament the lack of political commitment by Nigerian authorities to ensure that all the girls are accounted for or found.24Jerry Emmanson, ‘Parents Beg For Release Of 92 Chibok Girls,’ Daily Leadership, June 2023 Additionally, Chibok remains a target for Boko Haram, with property damage reported and residents and security operatives killed and abducted.25Sahara Reporters, ‘Breaking: Boko Haram Terrorists Attack Chibok Community, Displace Hundreds Of Residents,’ 23 August 2022; Uthman Abubakar, ‘Boko Haram attacks Chibok, kills two, loots foodstuffs,’ Nigeria Punch, 21 December 2023

However, Nigeria’s leadership and regional response demonstrate the potential positive benefits of effective military leadership and coordination that fosters relationships between neighboring countries’ militaries, as well as the development of a culture that values innovation, community engagement, and respect for human rights in maintaining regional peace and security. In the government’s efforts to win back the hearts and minds of its citizens in the fight against Boko Haram, the innovative approaches of the MNJTF underscore the importance of implementing military strategies alongside non-military measures rather than as an afterthought.

Visuals produced by Christian Jaffe.