The reverberations of the war in Gaza since the 7 October Hamas-led attack on Israel go well beyond the Gaza Strip. This Q&A looks at the local, regional, and international aftershocks of the fighting and is based on our recent webinar briefing led by ACLED President and CEO Clionadh Raleigh, who comments on Africa and presents the work of ACLED’s Palestine Researcher Nasser Khdour, Middle East Regional Specialists Ameneh Mehvar and Luca Nevola, and North America Research Manager Kieran Doyle.

What’s special about the cross-border dimensions of the war in and around the Gaza Strip?

Clionadh Raleigh: Gaza is a global event, despite the fact that the area itself is quite small and has just 2 million Palestinians living there. The international ramifications of the conflict are quite unique. That’s in part because it has engaged and ignited quite a lot of the antagonisms that are felt around Israel regionally and internationally.

Many people felt the Gaza conflict would enliven what was a declining jihadi general movement. We certainly see heightened activity from actors like Yemen’s Houthis, and triggered antagonisms in Syria and Iraq. But jihadi movements have very different reactions to Hamas and its fight against Israel. Al-Qaeda congratulated Hamas; the Islamic State (IS), which does not prioritize confronting Israel and seems to be involved in a kind of purity contest with all other jihadi groups, did not. They have tried to encourage individuals to stage revenge attacks, especially in the West, but it has had little effect so far.

Instead, the dominant reaction of the world has been focused on what’s happening within Gaza, what Israel is doing, US support for Israel, an outsized impact on domestic politics — for instance in the UK and mainly the US — and Iran’s continuing attempts to obstruct Israeli influence in the Middle East.

How does the latest war in Gaza compare to other conflicts around the world?

Nasser Khdour: The Gaza war is one of the world’s deadliest current conflicts, with more fatalities than the wars in Sudan and Ukraine. Despite reporting limitations, so far we have recorded more than 37,500 Palestinians killed. This figure includes both civilians and fighters; the Israeli government estimates more than 15,000 of those killed were combatants.

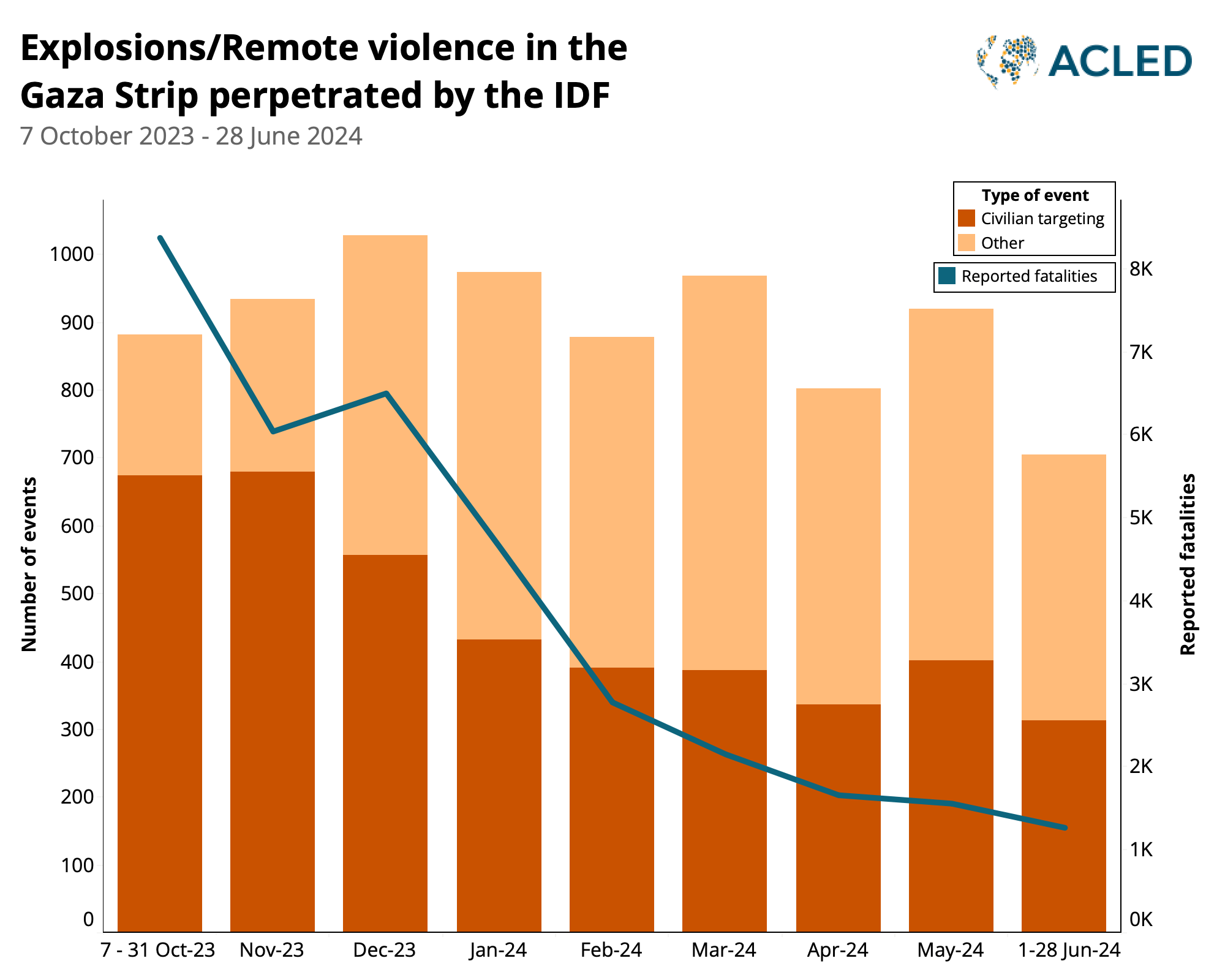

This chart above shows what we call ‘remote violence’ involving Israeli forces in the Gaza Strip since 7 October. These are mostly airstrikes and shelling and constitute about 80% of all political violence there. As you can see, the blue line showing fatalities per day has decreased over time, even though the number of events remains relatively high. One explanation is that the number of aerial or shelling events that targeted civilians and civilian infrastructure — the red area in the chart — has gradually decreased over time. Another reason is that during the past three months drone and helicopter attacks have increased compared to the first months of the war, when Israel made heavier use of fighter jets and large bombs.

Much of the narrative about the Gaza war revolves around the Palestinian militant group Hamas. Is that accurate?

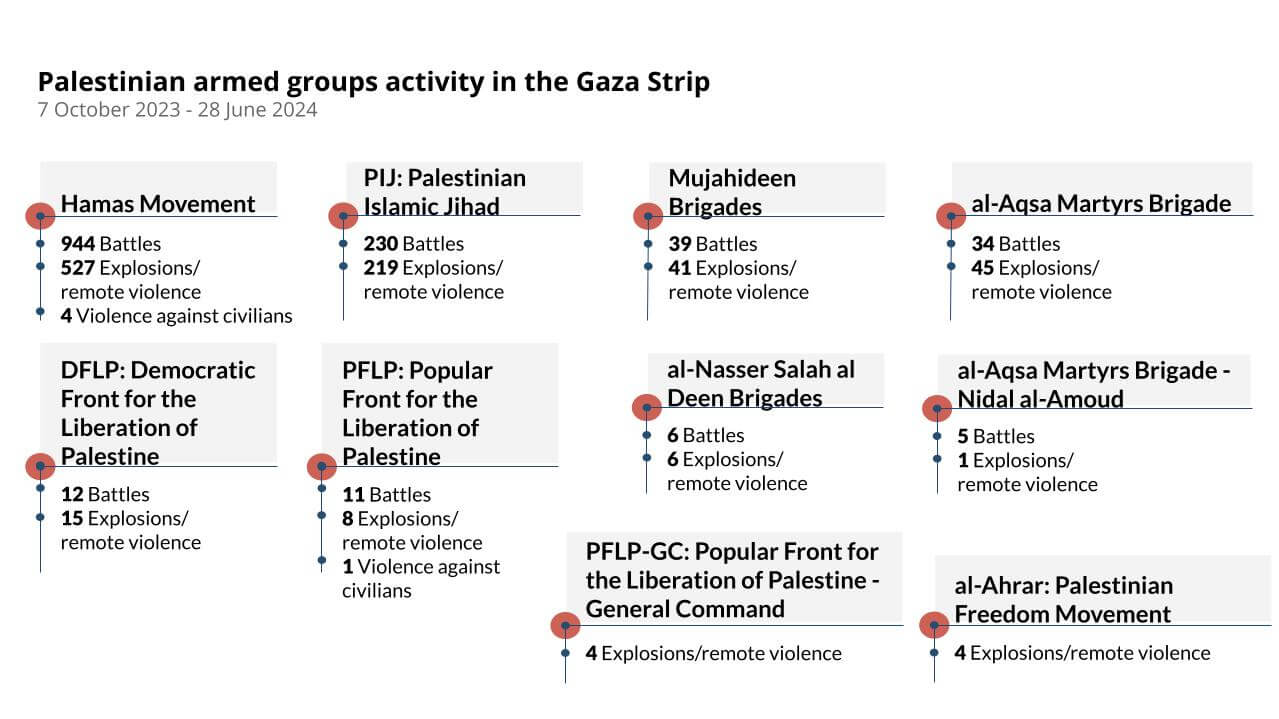

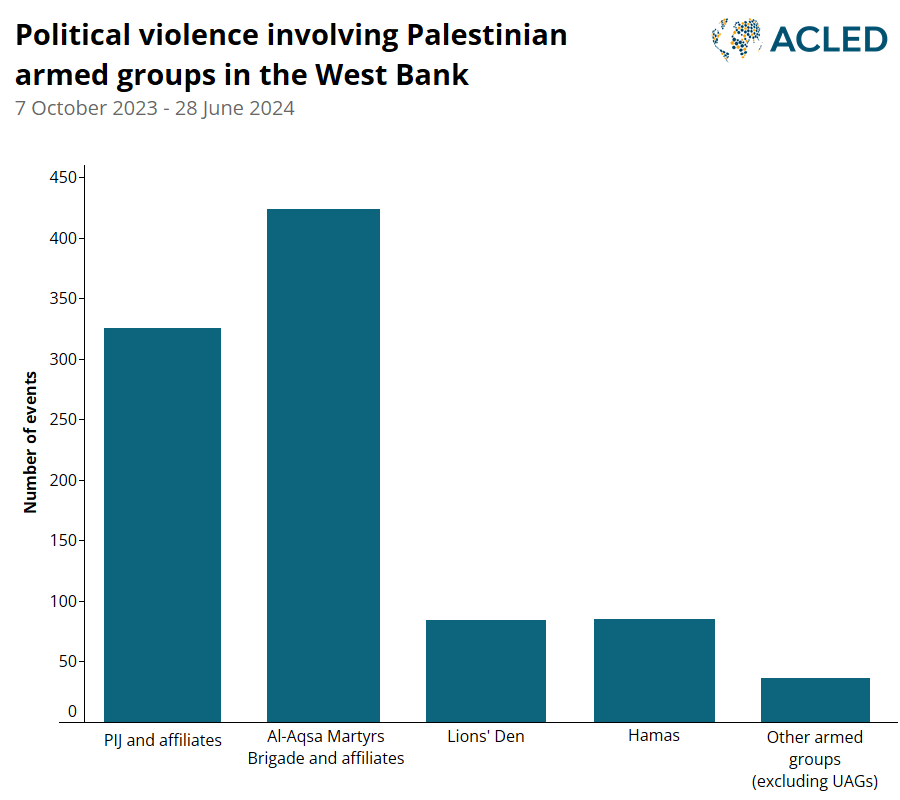

Nasser Khdour: Hamas has been the de facto government in the Gaza Strip since 2007, and since 7 October the group has been involved in about 90% of violence targeting Israeli forces, at least in terms of battles, one category of events that ACLED records. But Palestinian Islamic Jihad (PIJ) has also been very engaged, and overall there are 10 armed groups engaged on the Palestinian side of the war. Hamas, PIJ, and two others are Sunni Islamists, but others are affiliated with secular or even communist parties.

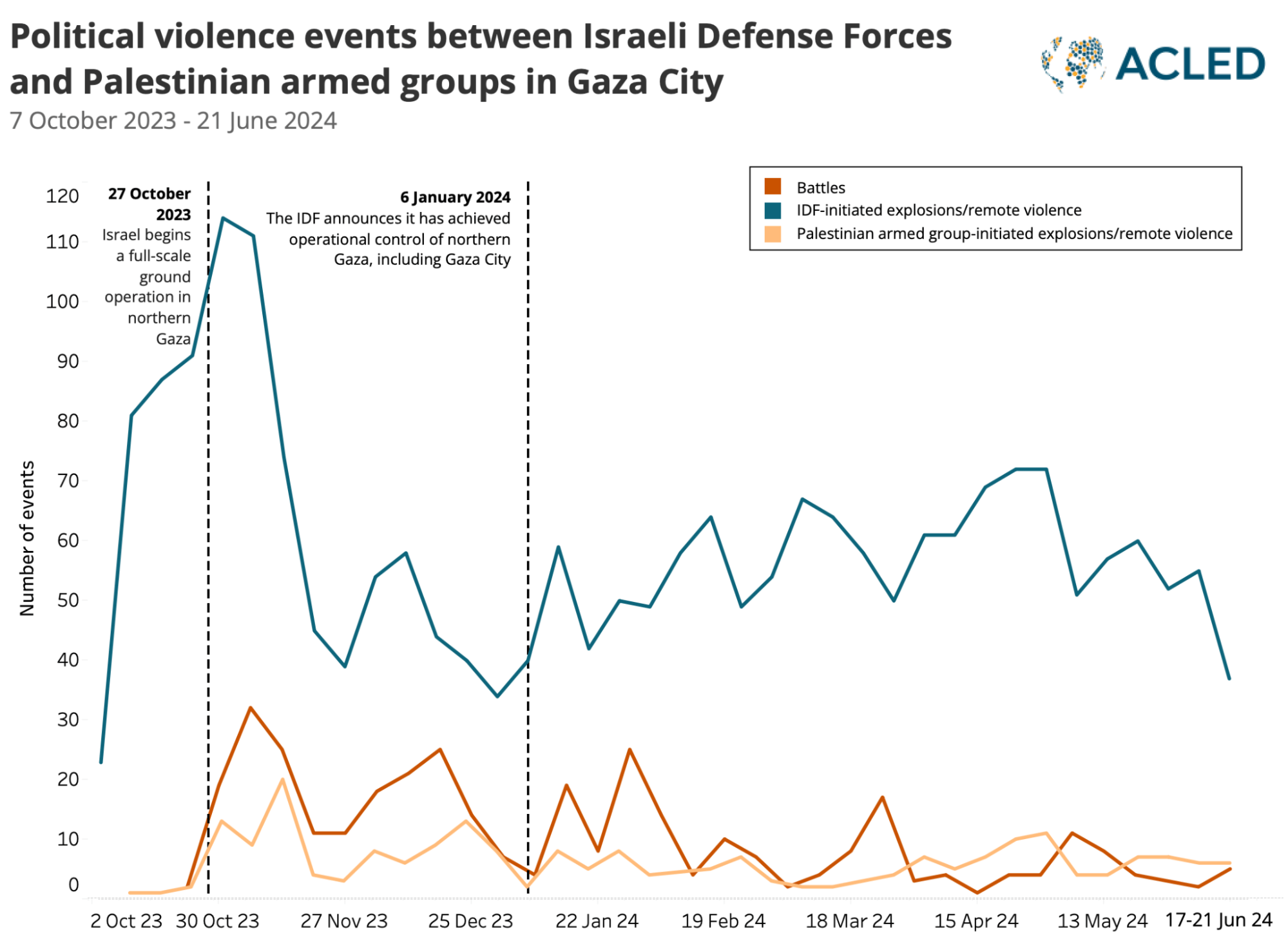

The evidence we have indicates that these groups will prove hard to defeat entirely. During Israel’s latest offensive in Rafah, in May, Palestinian armed groups were more often launching remote violence attacks than being forced into direct confrontation — a first since the conflict began. We recorded at least 24 Israelis killed in the Rafah ground operation, mainly by snipers, booby-traps, and various kinds of missiles. Hamas has managed to reorganize itself again and again — and it is still capable of fighting everywhere in Gaza City — so violence in the Gaza Strip will likely continue.

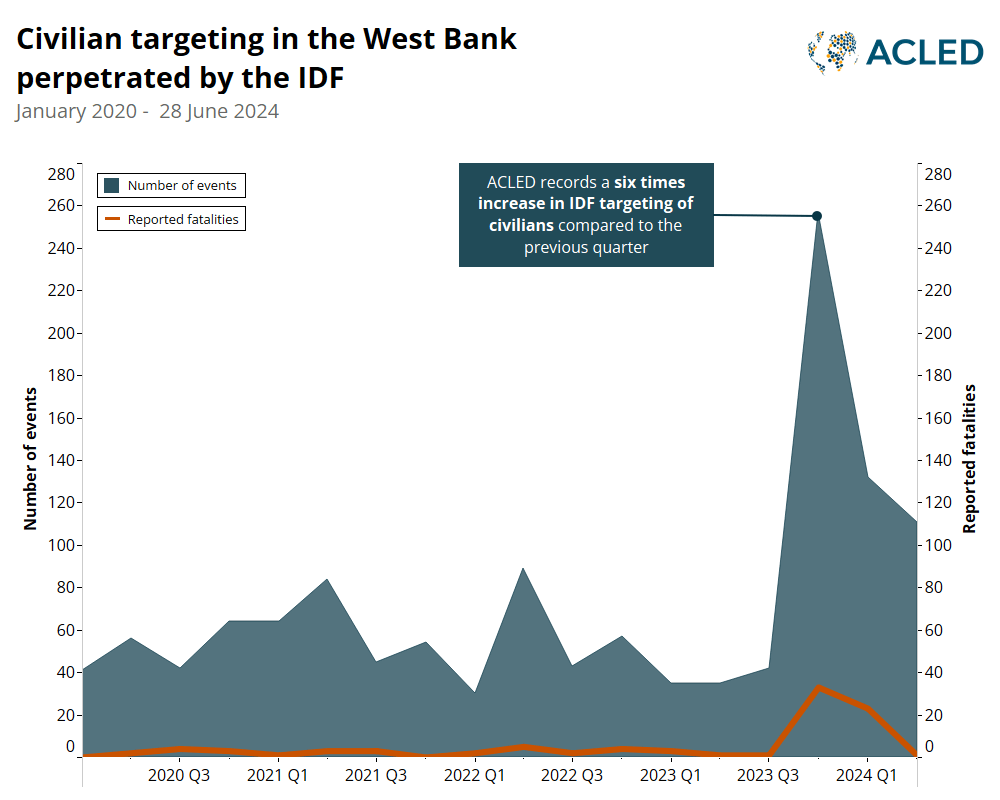

How has the fighting in the Gaza Strip affected security in the West Bank, where Palestinian life is run by another group, the Fatah-led Palestinian Authority (PA)?

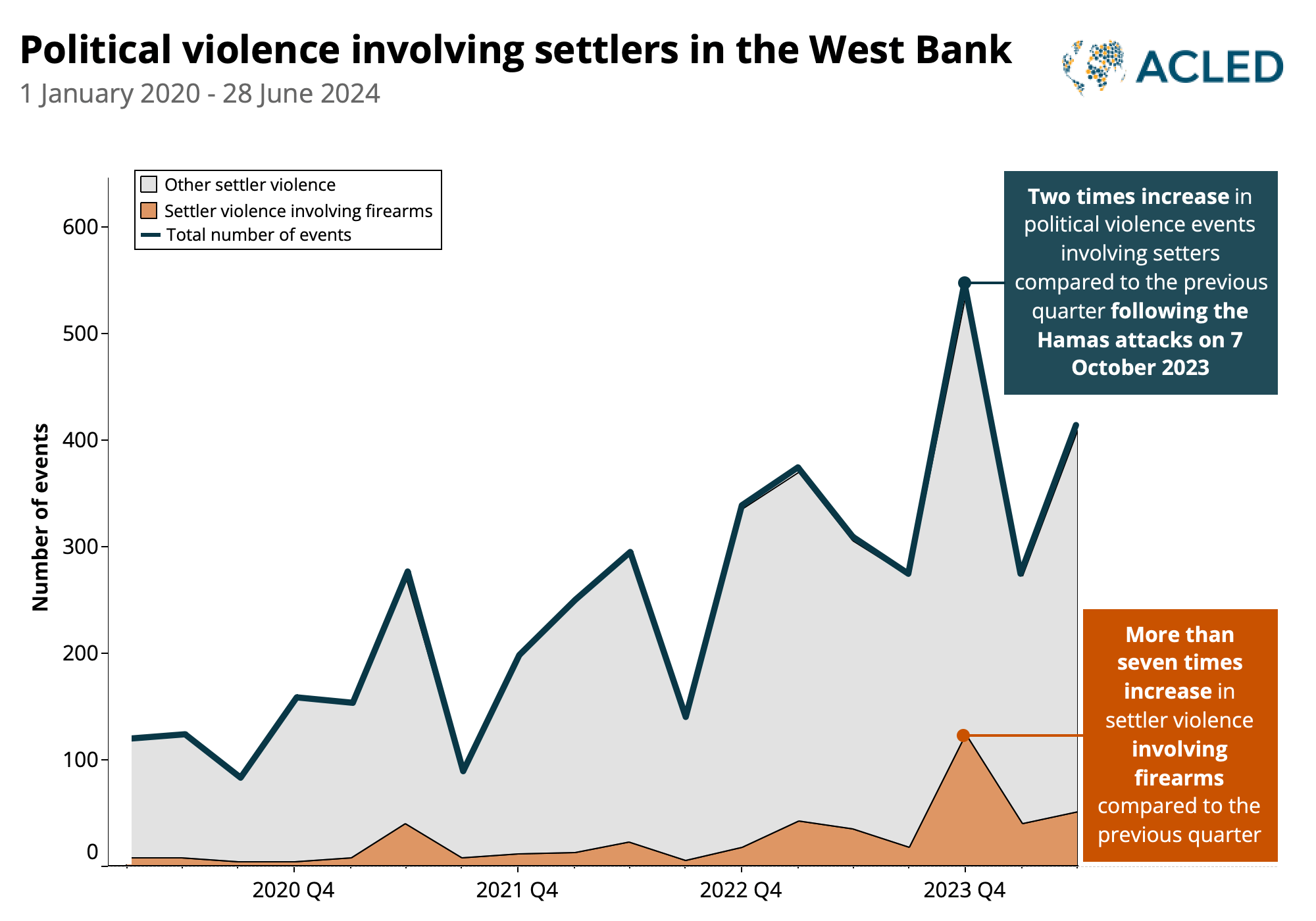

Ameneh Mehvar: Security has significantly declined since October in the Israeli-occupied West Bank, where 3 million Palestinians and about 500,000 Israeli settlers live. Some pre-existing negative trends have drastically intensified. Settler violence in particular has escalated, notably from armed settlers and settler security squads.

In the last nine months, armed settlers were responsible for over 200 incidents that killed at least nine Palestinian civilians in the West Bank. In another five cases, Palestinian civilians were killed when settlers and soldiers fired at the same time. Soldiers alone killed another 200 unarmed Palestinians and about 350 others who were armed. Palestinians meanwhile killed three civilian settlers and at least 11 Israeli soldiers in the same period.

Palestinian armed groups’ activity in the West Bank has been building up for the past three years after being largely absent from the region for more than 15 years. At least half of this activity is firefights while responding to Israeli raids and operations, while the rest includes attacks on soldiers, checkpoints, and military posts, as well as shootings toward settlements and Israeli towns beyond the Green Line. Taken together, all signs point to worsening conflict in the West Bank, especially given the deepening pro-settler bias in the current Israeli government. It’s worth pointing out that Hamas has claimed responsibility for less than one-tenth of Palestinian actions by armed groups in the West Bank, as shown in the chart below. Note that many more events are unclaimed, so there is no clear indication if Hamas was involved or not in those.

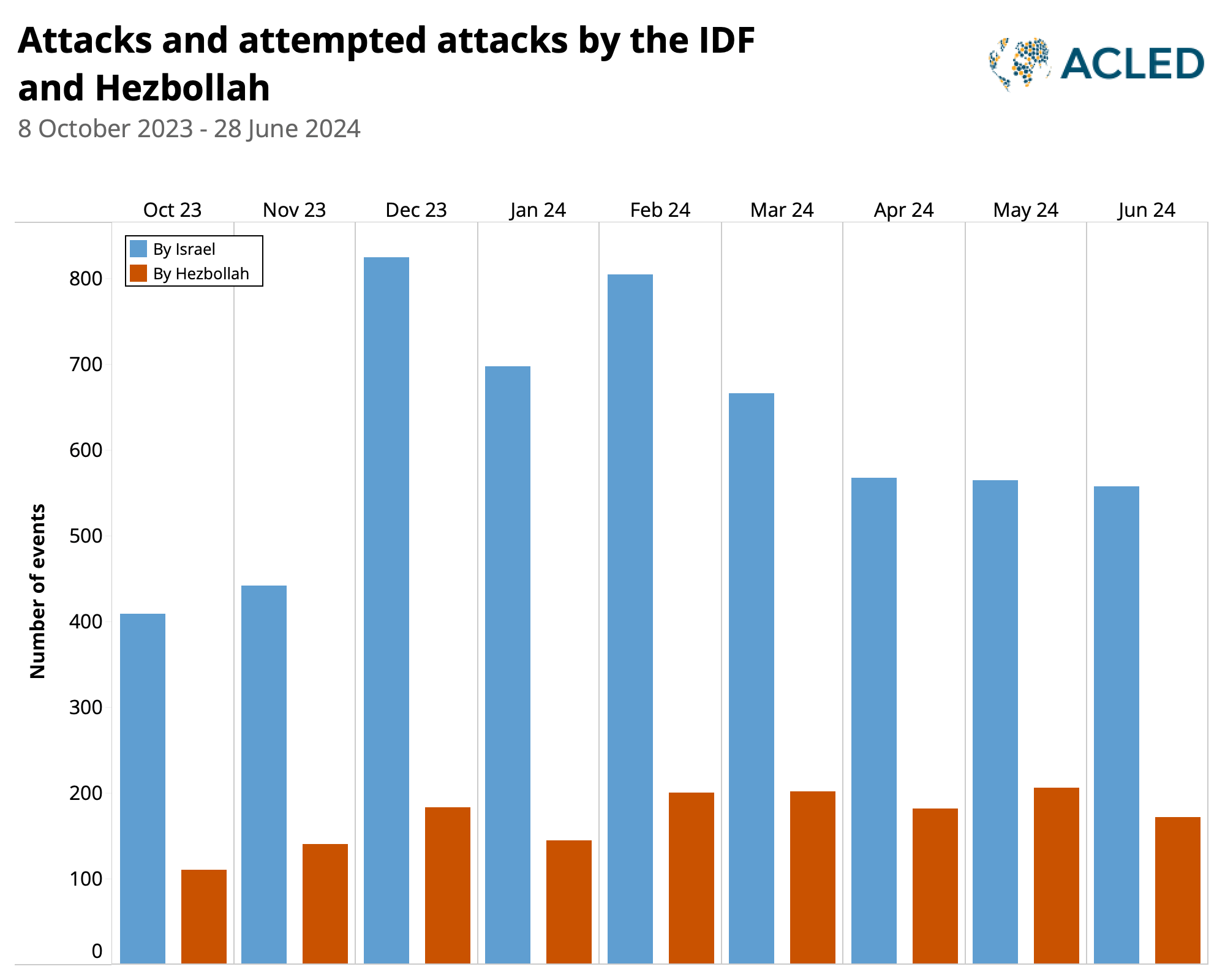

What do the data say about the worsening situation on the Israel-Lebanon border?

Ameneh Mehvar: Israeli forces have engaged in near-daily cross-border fire with Lebanese Hezbollah along Israel’s northern border since 8 October. Over 7,000 combined attacks have been recorded so far, though the intensity of fire exchanges has fluctuated.

While Hezbollah has kept Israel busy in the north, the hostilities have been kept below a certain threshold. This means violence has been largely confined to border areas, avoiding extensive civilian casualties and infrastructure damage in both countries. But in the absence of a ceasefire in Gaza the conflict has gradually intensified, and both sides have increasingly targeted locations deeper inside each other’s territories.

The most intense phase of escalation happened from May to around mid-June: After Israel’s incursion into Rafah, Hezbollah intensified attacks with new tactics and weapons, including using missile-firing drones, advanced Falaq-2 rockets, and air defense missiles targeting Israeli jets. Hezbollah also targeted cities in Israel that had not been evacuated. In June, Hezbollah also launched increasingly larger salvos of rockets that sparked extensive forest fires across northern Israel. This increased domestic pressure on the Israeli government to show a more forceful response.

Following this escalation, both sides also showed more aggression in their rhetoric. Notably, the Israeli military suggested it had “approved and validated” plans for a potential offensive into Lebanon. While it’s likely that Hezbollah’s latest escalatory moves were an attempt to strengthen deterrence in anticipation of the winding down of IDF operations in Gaza — which would enable Israel to redirect its efforts to the north — as hostilities drag on, the risk of crossing red lines due to accidents, miscalculations, or misunderstandings will continue to increase. Even if a ceasefire in Gaza is reached and Hezbollah stops its attacks, launching an offensive in Lebanon will remain a political decision for the Israeli leadership.

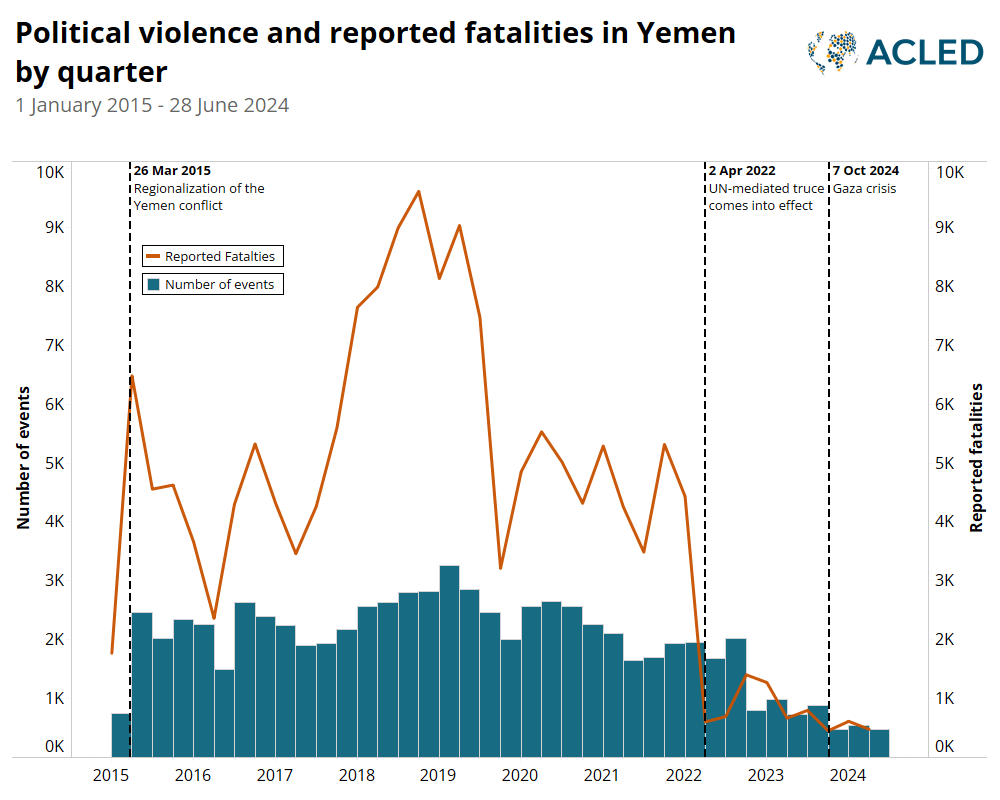

The Gaza war opened up an unexpected faultline further south in Yemen. The Houthis, who now rule two-thirds of the Yemenis, emerged as self-proclaimed champions of the Palestinian cause, attacked Israel, and held global trade at bay with targeted attacks in the Red Sea. How did this happen?

Luca Nevola: The Houthis’ stated aim is to impose an embargo on Israel and to halt military operations in Gaza. Yet to fully understand the motives and political relevance of their activity in the Red Sea, we must take a step back and analyze the domestic situation in Yemen.

In the year prior to the Gaza war, Yemen transitioned into a low-intensity conflict. It remains at the lowest level recorded by ACLED since the war began in 2015. A better grip on local battlefronts allowed the Houthis to shift their resources toward attacking international shipping in the Red Sea. The Houthis’ actions have disrupted global trade and allowed them to project themselves as a regional power, despite the low lethality of the attacks and the low percentage of hits on ships.

In turn, the Red Sea crisis allowed the Houthis to divert popular attention away from internal economic problems and garner significant domestic consensus. Yemenis have given massive support for demonstrations organized by the Houthis in support of Palestine since October. The Houthis then leveraged their new strength to recruit and consolidate their military grip on northern Yemen.

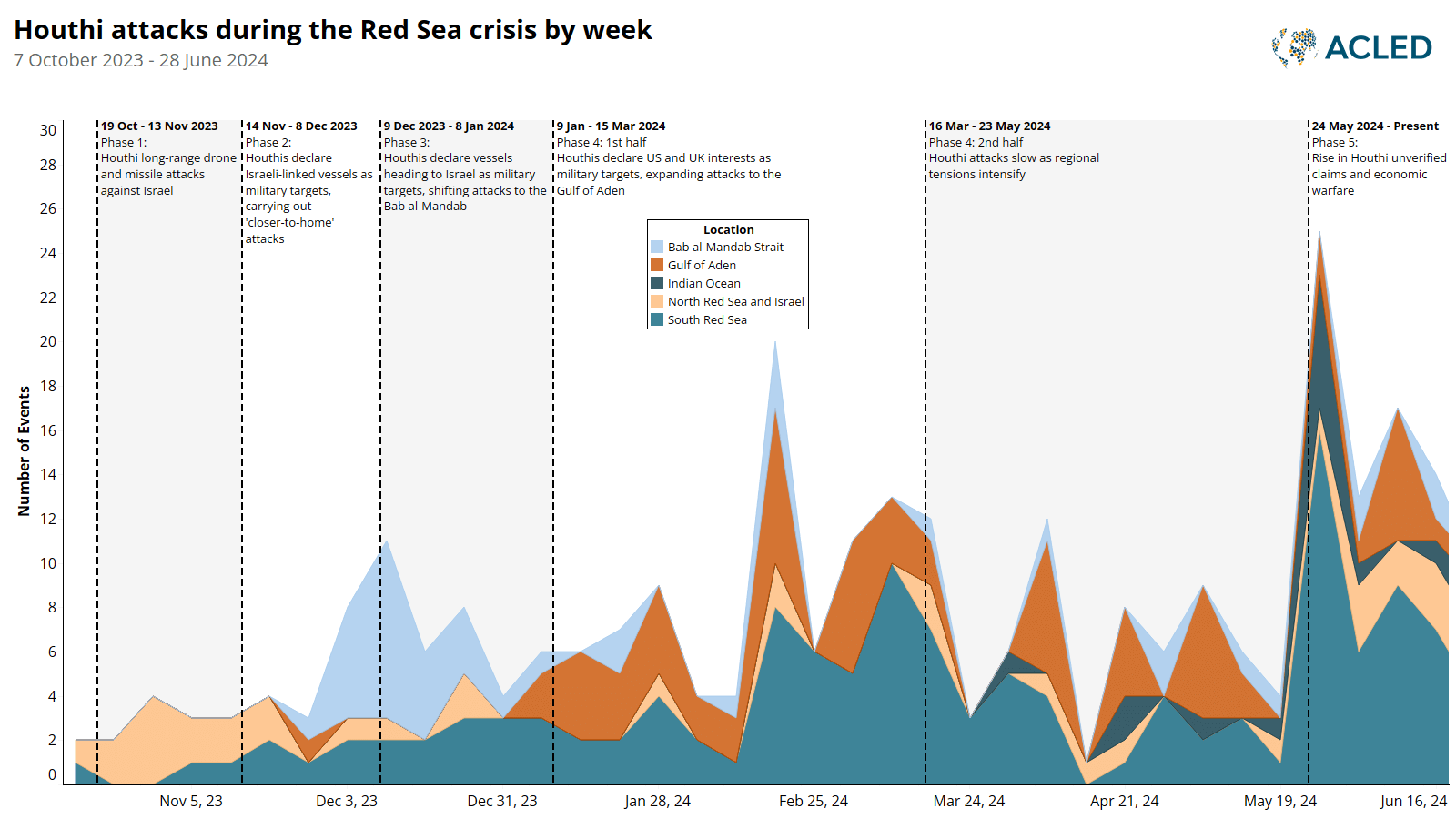

Houthi tactics have evolved through several phases of gradual, controlled escalation on the timescale above. Each phase has also seen the development of multiple new dynamics, including:

- A geographical expansion of attacks from the northern Red Sea to the southern Red Sea, the Bab al-Mandab, then to the Gulf of Aden. More recently the Houthis have claimed attacks in the Indian Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea.

- An expansion of military objectives, from ineffective, almost symbolic strikes on Israel itself, then on Israel-linked vessels, then on all vessels headed to Israel, then on US and UK interests, and now on vessels in the Mediterranean.

- Symbolic responses to regional and international political developments.

- The release and deployment of new weapons, including hypersonic missiles and drone boat attacks.

- Coordination with other regional actors, including Shiite militia in Iraq.

- Crackdowns on domestic and international NGOs inside Yemen itself.

A US-led coalition and Yemen’s Internationally Recognized Government are leading efforts to counter the Houthis. Have these had any impact?

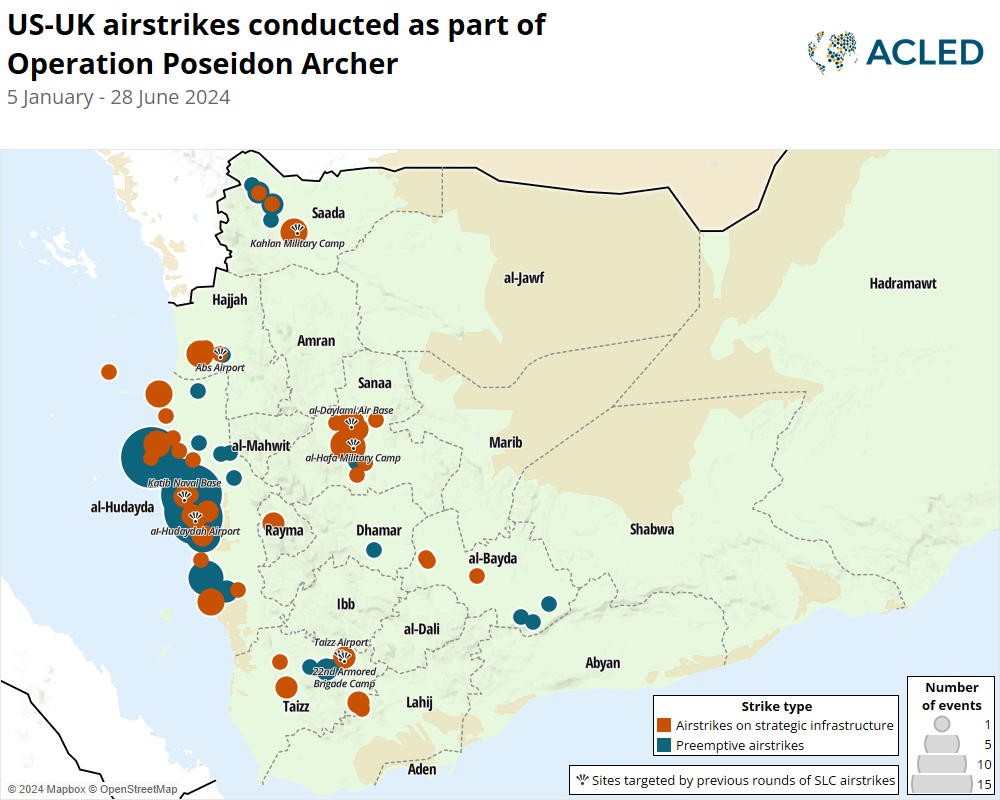

Luca Nevola: US-led efforts range from economic pressure to increased frequency of US airstrikes in Yemen, initiated in early January and known as Operation Poseidon Archer. These airstrikes are part of a tit-for-tat retaliatory pattern paralleling Houthi attacks in the Red Sea, and vice versa.

Between January and June we recorded broadly five main rounds of airstrikes. The majority of the strikes were preemptive strikes on Houthi sites with missiles and drones already ready to be launched, as shown in blue on the graph above. We are now recording a new pattern, with more frequent strikes on strategic infrastructure, in orange above.

Operation Poseidon Archer involved the highest number of US airstrikes in the Middle East recorded by ACLED since 2018, when Washington was engaged in the war against IS in Syria and Iraq. It’s worth noting too that around 80% of the locations targeted by the US coincide with those bombed by the Saudi-led Coalition in Yemen after 2015. Yet the US airstrikes have had limited impact on degrading Houthi military capacity.

How will the Yemeni dimension of the Gaza conflict develop? Will it be toward more internationalization, wider geographic extent, or more threats to shipping?

Luca Nevola: Houthi activity in the Red Sea cannot continue at these levels indefinitely. In fact, escalatory tactics have inherent limits, unless new red lines are crossed to expand military targets and areas of operation. For instance, an all-out war between Hezbollah and Israel would provide the Houthis with a justification for renewed anti-Israel operations. But even if fighting in Gaza winds down, the Houthis will look for opportunities to consolidate on the internal front, repress dissent, mobilize their fighters, project their power externally, and strengthen coordination with the Iran-backed ‘axis of resistance.’ The Houthi leadership appears to be less and less interested in accommodation with Western actors, or seeking international recognition as the new government of Yemen.

The US now considers the Houthis a long-term threat. But Washington’s ability to degrade Houthi military capabilities has proven to be limited, and Houthi attacks are continuing and increasing. The US also lacks the level of diplomatic and other leverage needed to constrain their activity. Its options seem limited to increasing economic sanctions, brandishing the threat of classifying the Houthis as a Foreign Terrorist Organization, pressuring Saudi Arabia to stall internal Yemeni peace talks, or supporting local actors in Yemen against the risk of further Houthi advances.

In short, a comprehensive peace deal that normalizes life for Yemenis and Yemen’s rulers still looks distant.

Have the Gaza war and its many images of suffering Muslims given new impetus to the cause of Islamists like the Houthis elsewhere, for instance in Africa?

Clionadh Raleigh: There has been great concern that jihadi movements are relocating and embedding themselves in Africa. As jihadi movements have faced a general decline in recent years, the continent has seemed like fertile ground to gain territory and influence. And while there are relatively few rebel or insurgent groups within African states, violent jihadi groups are responsible for a tremendous share of the political violence there. But despite these groups’ violent Islamist perspective, Gaza has not been used as a justification for them stepping up attacks. In part, that’s because the relationship of African countries to the Palestinian cause, to Israel, and even to the US is much more complicated than in, say, the Middle East.

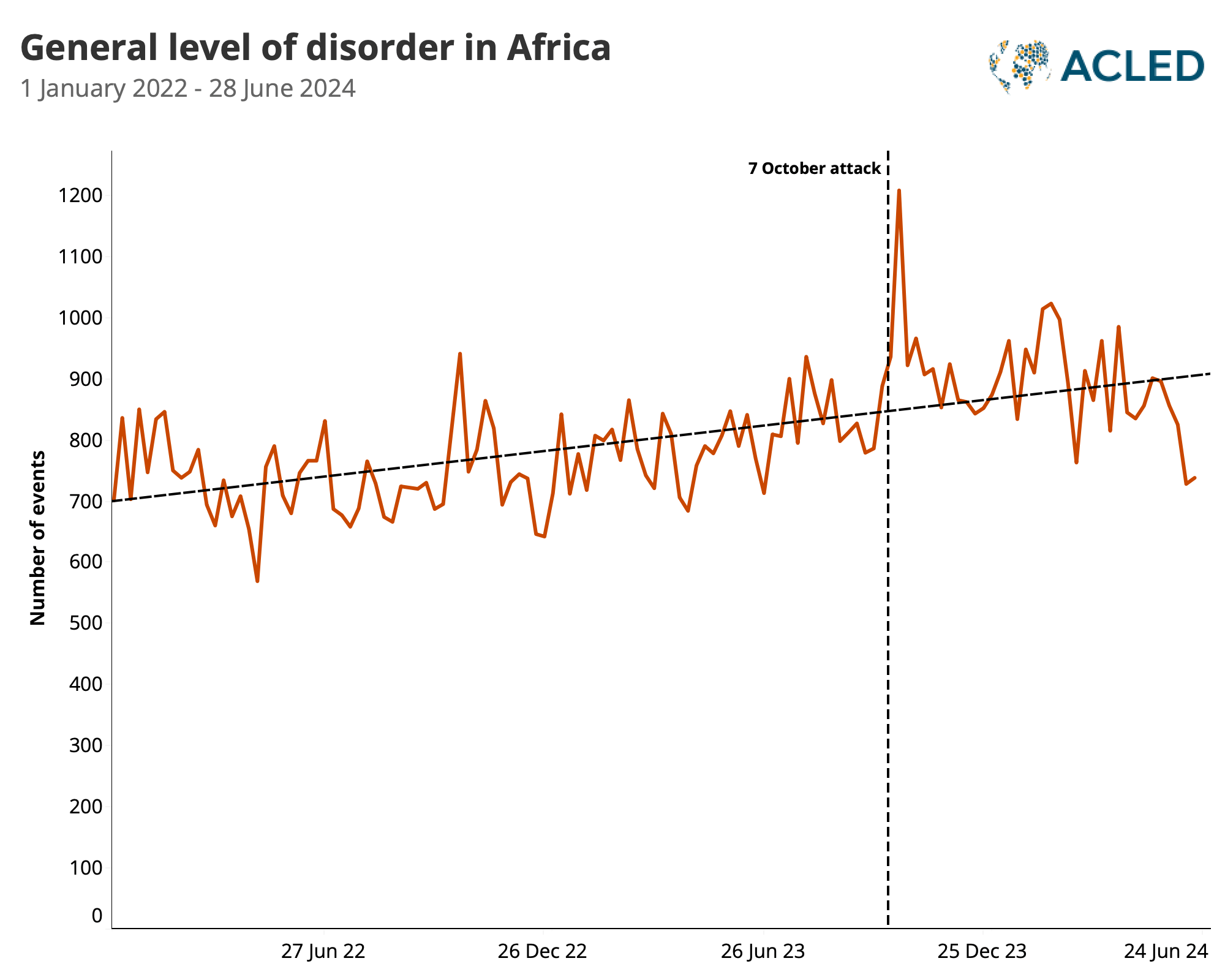

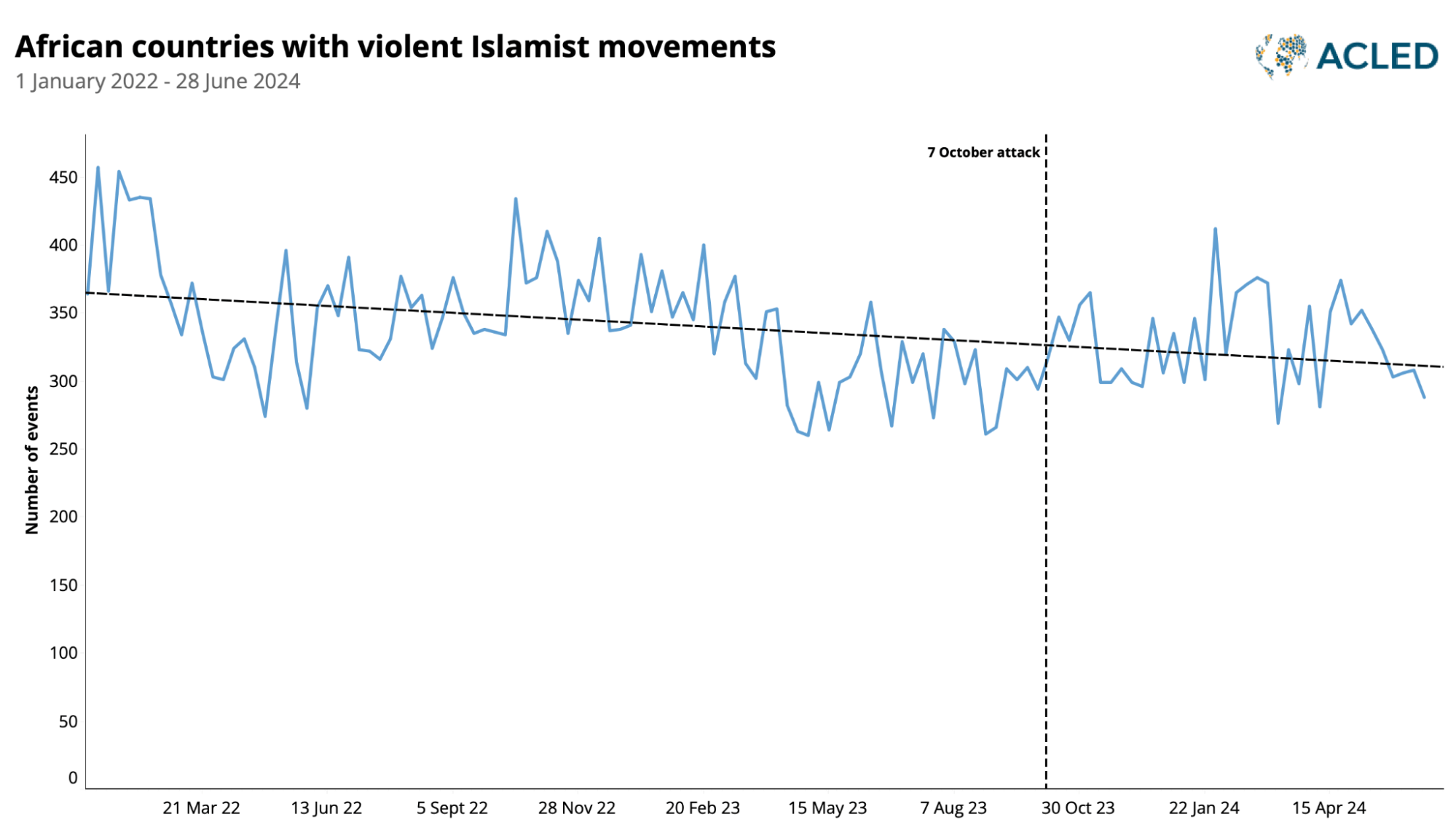

There has been a kind of stability in the pattern of disorder across African states over the past two years, as the chart above shows. A spike seems to coincide with the 7 October period. But if we look at the chart below showing only those countries with violent Islamist movements, we don’t see the same spike. We can also see that, as a violent organizing principle, jihadism is in decline.

Especially in the Sahel, there are some Islamist groups with an international focus, where external interests are very actively involved. But in general, African Islamists tend to be national in nature — and even in the Sahel, a significant focus of dominant groups representing an al-Qaeda affiliate and an IS affiliate is really to fight against each other rather than to fight a government. So one reason they are not responding to the Gaza conflict is because they are engulfed with conflicts that are happening extremely locally. This internal competition between jihadi groups means that they are not as successful as groups like al-Shabaab that are highly focused on national objectives.

Another reason that brand jihadism has declined is because it no longer offers the same opportunities for alliances: Other local or national groups often do not want to associate with a jihadi group due to the extreme reputational and agency costs. Part of this reasoning is that jihadi groups are associated with such incredible rates of violence, both against Muslims and non-Muslims. They attract too much outside interest and internal risk. Military attacks on Islamist violent groups in Africa have also been successful, especially when based on air attacks. So jihadist branding is no longer particularly attractive.

What picture emerges from ACLED data on the protests relating to the Gaza war elsewhere in the world?

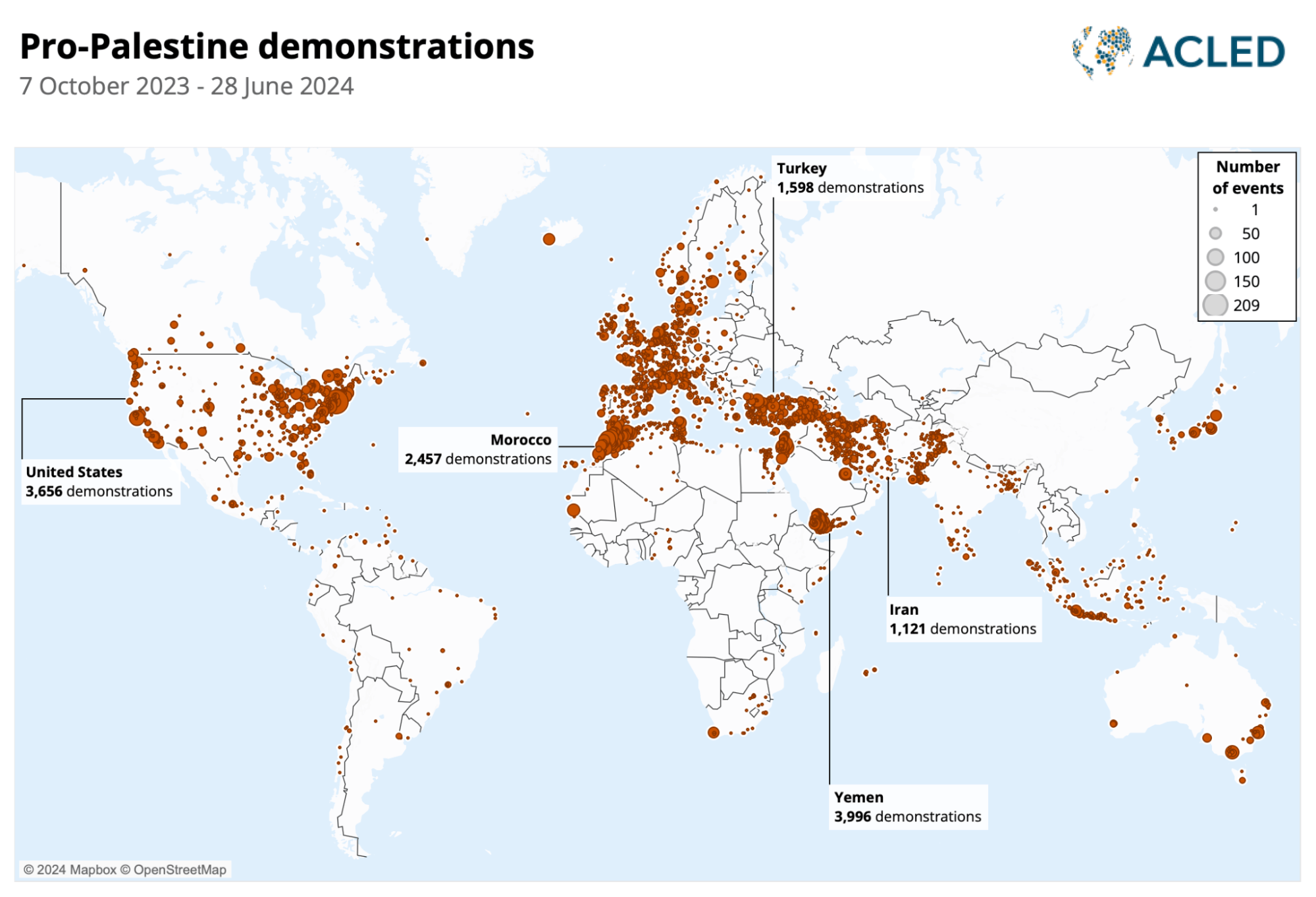

Kieran Doyle: If we look at the number of pro-Palestine demonstrations plotted on a world map, as below, we see that Yemen has had the highest number, with 3,996 demonstrations, followed closely by the United States (3,656), Morocco (2,457), Turkey (1,598) and then Iran (1,121). There have also been demonstrations throughout Europe, East and Southeast Asia, in Australia, and scattered across sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America.

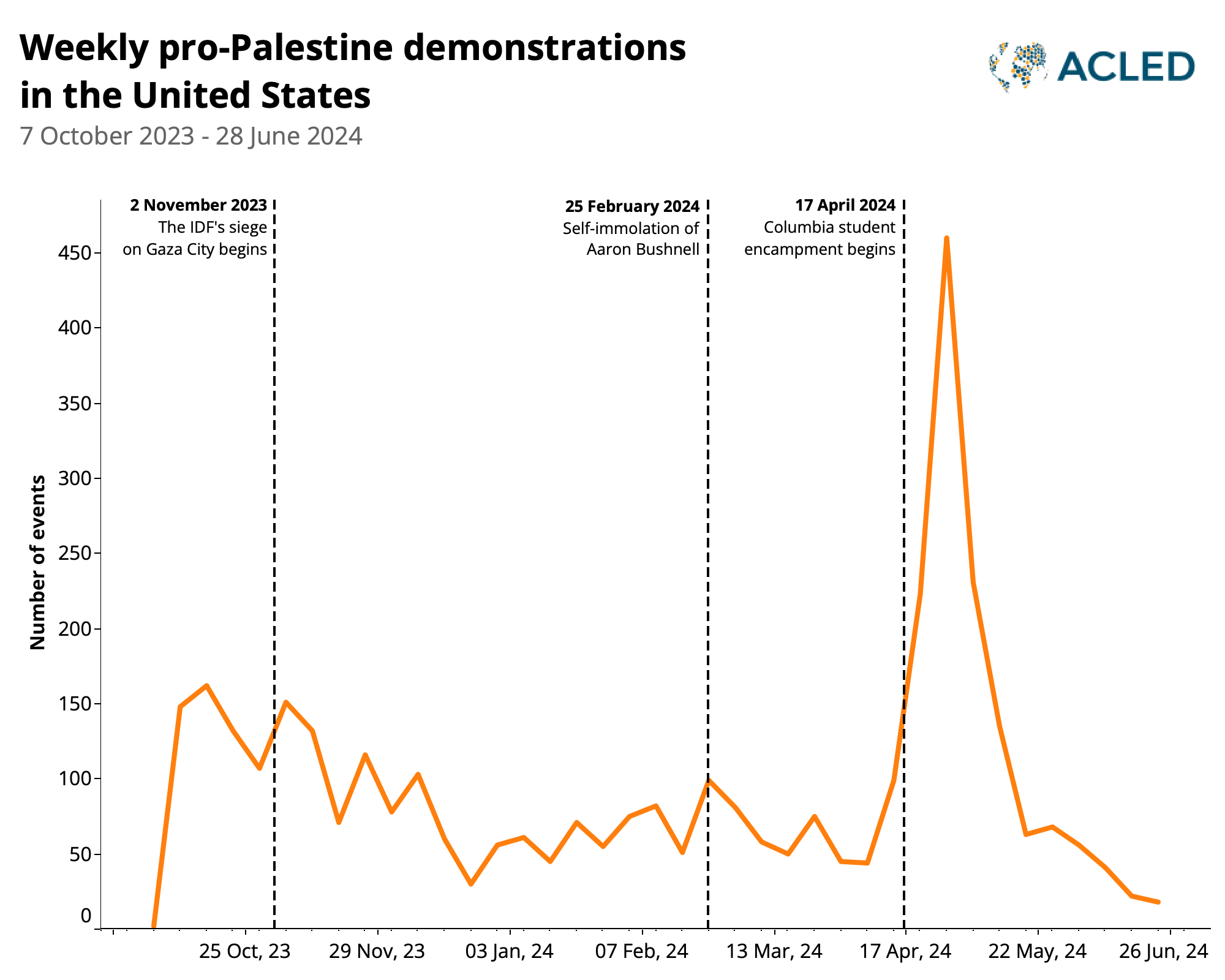

The biggest surprise is the extent of the pro-Palestine movement since the beginning of the war in the United States, which has traditionally been very supportive of Israel. There is quite a concentration of demonstrations on the East Coast. The top three states with the most demonstration events are New York, California, and Massachusetts. However, since the beginning of the Gaza war, we recorded demonstration events in all 50 states and in Washington, DC.

ACLED data also record these demonstration events at the county and city level. For instance, Hennepin County, Minnesota, and Wayne County, Michigan, have a very high number of pro-Palestine demonstration events relative to other demonstration drivers. These protests — which were often critical of President Joe Biden’s continued support for Israel despite the high death toll — proved to be a good barometer for the political future. Locations with the highest number of pro-Palestine demonstrations are often the same places where large numbers voted ‘uncommitted’ in the Democratic primary.

Beginning in mid-April, demonstrations led by students on university campuses represented the highest levels of Palestine solidarity demonstrations in the United States since the beginning of the war. An encampment-style demonstration at Columbia University, which initially lasted two weeks and resulted in hundreds of arrests, saw a surge of similar demonstrations across the country. ACLED data show that the overwhelming majority of these demonstrations on university campuses from 7 October 2023 to 5 July 2024 — 98% — remained peaceful.

Do you foresee pro-Palestine demonstrations at either of the upcoming Democratic or Republican party conventions?

Kieran Doyle: I think you can expect there to be protests at both of them. Indeed, most major domestic political events in the lead-up to the election will likely see some kind of protests related to the war in Gaza. But it’s not clear how widespread or how large those will be. As shown on the graph above, there’s been a decline recently, mostly as universities’ academic terms end and many of the students participating in the encampments have gone home. For the future, a lot will depend on what happens when university terms restart later in the year and, of course, what happens in the Gaza war and how the United States’ policy toward it evolves.

This Q&A is based on ACLED’s webinar briefing on ‘Reverberations in Gaza’ held on 3 July 2024, which you can watch in full on ACLED’s YouTube channel.

For more information, see the ACLED Israel & Palestine focus page.