Situation Update | July 2024

Anti-tax demonstrations spread nationwide and highlight Kenya’s structural challenges

19 July 2024

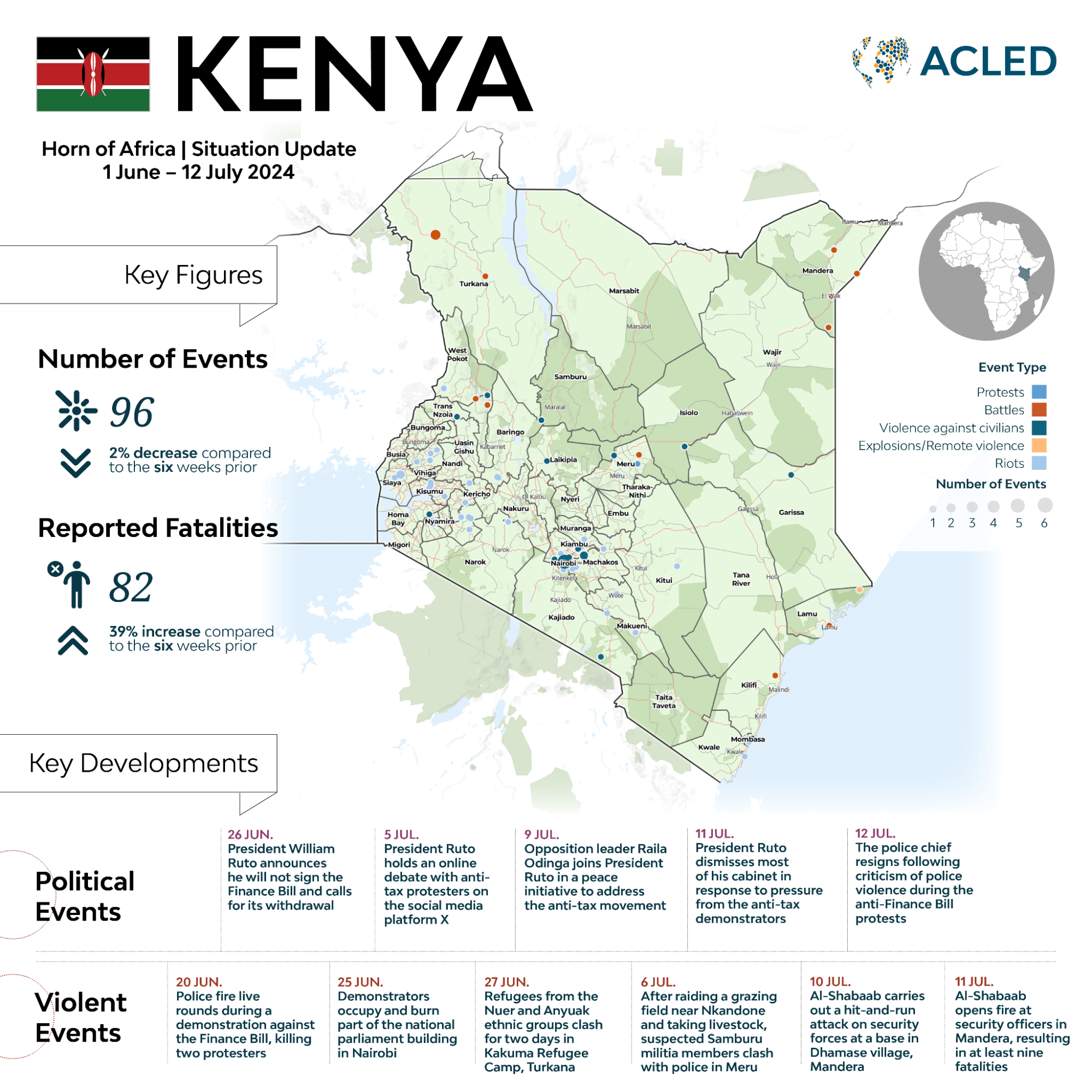

Kenya at a Glance: 1 June to 12 July 2024

VITAL TRENDS

- From 1 June to 12 July 2024, ACLED records 96 political violence events and 82 reported fatalities in Kenya. Most events took place in Nairobi, which saw 21 political violence events linked with anti-tax demonstrations.

- Turkana and Mandera counties had the highest number of reported fatalities, with at least 13 reported in Turkana and at least 11 reported in Mandera. The majority of fatalities in Turkana were linked to an armed clash in Kakuma refugee camp between Nuer refugees and Anyuak refugees.

- The most common event types during the reporting period were riots, with 52 recorded events, followed by violence against civilians, with 26 recorded events. The majority of riots were in Nairobi, with eight recorded events.

Anti-tax demonstrations spread nationwide and highlight Kenya’s structural challenges

Since 18 June, Kenya has been engulfed in deadly unrest. Thousands of predominantly young demonstrators, self-identifying as Generation Z, took to the streets — initially to protest the controversial 2024 Finance Bill, and then broadening their aims to demand that the government address inequality, corruption, and elite politics. The 25 June storming of Kenya’s national parliament building in Nairobi was a violent peak of the public outcry, as demonstrators burned vehicles in front of the Supreme Court and set the governor’s office on fire. It also brought to the fore the issue of excessive force in response to the demonstrations, as the Kenyan police fired live bullets to disperse the crowd at the parliament building, killing more than a dozen protesters and injuring hundreds. Rights groups have also accused security forces of carrying extrajudicial arrests and enforced disappearances of activists.1World Organisation Against Torture, ‘Kenya: enforced disappearances and extrajudicial killings must stop now,’ 28 June 2024; Olivia Kumwenda-mtambo and Mukelwa Hlatshwayo, ‘Kenya rights groups decry abductions as government cracks down on protests,’ Reuters, 5 July 2024 ACLED data indicate this movement has widespread support, and it has reached more counties in Kenya than past anti-tax protests. Moreover, violence has featured more heavily in the demonstrations both as a factor of new tactics from the demonstrators and the militarized response by police.

The movement spreads across Kenya

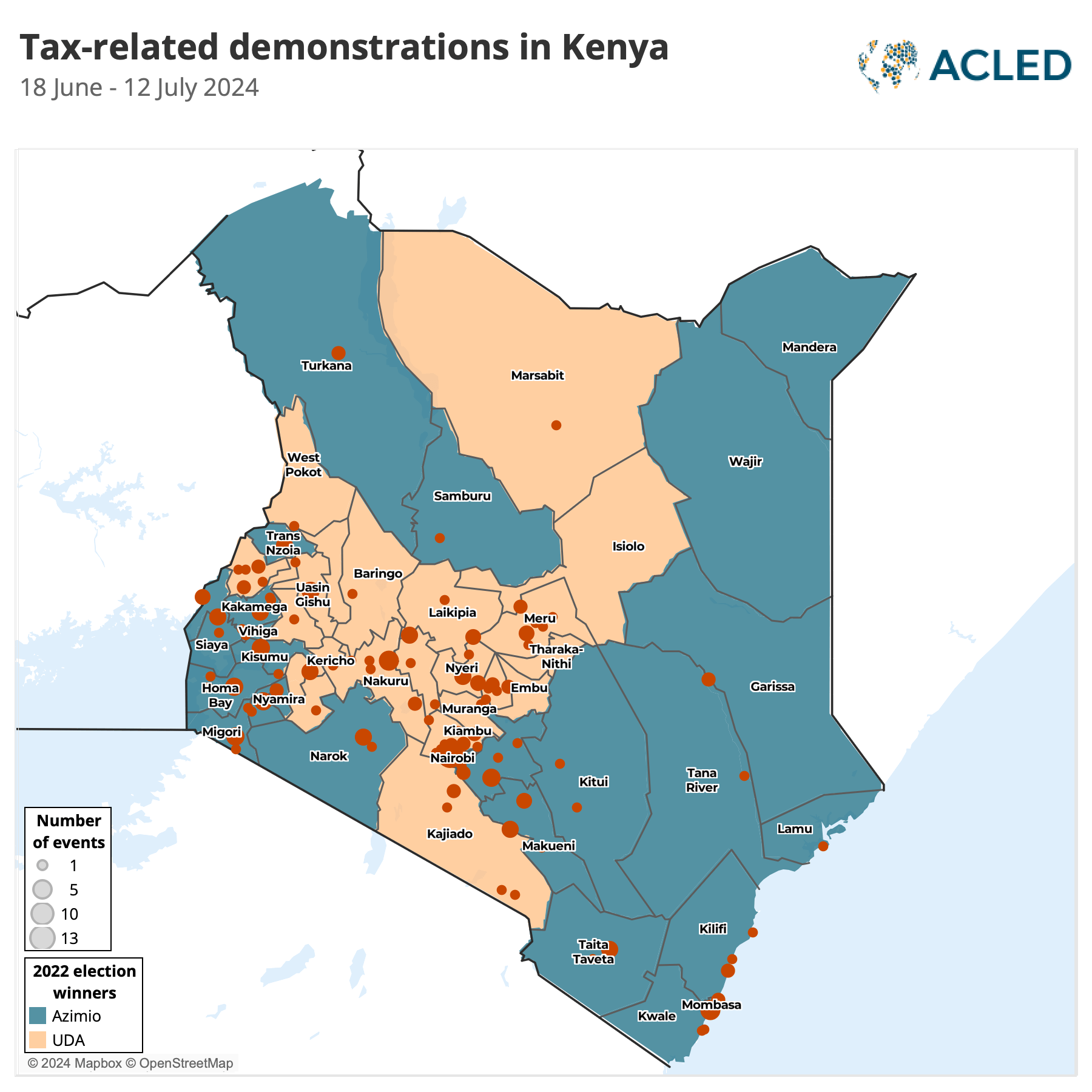

The anti-tax protests began in mid-June in Nairobi before expanding to 43 of Kenya’s 47 counties. The government has made some efforts to meet the movement’s demands: After demonstrators stormed the national parliament building in Nairobi, President William Ruto announced he would not sign the 2024 Finance Bill, which included new taxes on bread, diapers, and smartphones.2Basillioh Rukanga, ‘Five killed and parliament ablaze in Kenya tax protests,’ BBC, 25 June 2024 Ruto also vowed to cut spending on public officials’ benefits and dozens of redundant state enterprises.3Evelyne Musambi, ‘Kenya’s president warns of huge consequences after his effort to address an $80 billion debt fails,’ AP News, 10 July 2024 However, these promises did not put an end to the demonstration movement. Protesters across Kenya have remained in the streets to demand that President Ruto resign and to express broader dissatisfaction with corruption and the cost of living.4Khasai Makhulo, ‘Taking Charge: Gen Z Leads Historic Protests in Kenya,’ Center for Strategic and International Studies, 27 June 2024 The large participation of Gen Z in the protests is not the only unique factor of this movement. The demonstrations’ largely nonpartisan character is also significant, as it comes in contrast to last summer’s anti-tax bill protests organized by the Azimio la Umoja opposition coalition.5The Economist, ‘The political shifts beneath Kenya’s deadly “Gen Z” protests,’ 9 July 2024 Unlike the 2023 tax-related protests, the Gen Z movement expanded beyond the opposition coalition’s strongholds in western Kenya into counties like Kirinyaga, Kiambu, and Meru that voted for Ruto’s United Democratic Alliance (UDA) party in 2022 (see map below). Furthermore, some demonstrators have criticized Azimio leader Raila Odinga for proposing a dialogue between demonstrators and Ruto, reflecting a broader opposition to Kenya’s political elite.6The Nairobi Law Monthly, ‘Stay home, Agwambo: Raila faces Gen Z backlash over dialogue bid,’ 10 July 2024; Jurist News, ‘Gen Z Leads Digital Uprising Against Economic Injustice in Kenya,’ 10 July 2024

While these demonstrations have affected much of the country, the absence of the movement from certain areas illustrates the diversity of Kenyan politics and society. In particular, Tharaka Nithi, Elgeyo-Marakwet, Wajir, and Mandera are the four counties without recorded demonstrations during this anti-tax wave. Tharaka Nithi and Elgeyo Marakwet are Kenya’s sixth- and seventh-least populated counties, respectively, and ACLED records only 46 and 37 protest events in the two counties since data collection began in 1997.7Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, ‘2019 Kenya Population and Housing Census Results,’ 4 November 2019 While no single reason may explain the relative calm in these small counties, the German Institute of Development and Sustainability has highlighted the essential link between urbanization and today’s protests over the cost of living and poor service provision.8Lena Gutheil, ‘Kenya’s protests happened in every major urban centre – why these spaces are explosive,’ The Conversation, 27 June 2024 Notably, Tharaka Nithi and Elgeyo Marakwet have some of the lowest urbanization rates in Kenya, with Tharaki Nithi tied for the lowest urbanization of any county.9Symbiocity Kenya, ‘Urbanisation in Kenyan Counties,’ 2015 Conversely, ACLED records that Kenya’s seven largest cities account for 57 of the 215 anti-tax demonstrations since 18 June, approximately one-fourth of all events.

Meanwhile, in Kenya’s expansive northeast, Wajir and Mandera are two of Kenya’s three counties bordering Somalia, where distinct circumstances often localize the region’s politics. These two counties also did not participate in the 2023 demonstrations. For years, Wajir and Mandera have been at the epicenter of the al-Shabaab insurgency’s expansion over the border from Somalia (alongside Garissa and Lamu counties, which each experienced just one anti-tax demonstration). The Kenyan political establishment has historically marginalized the northeast. Both the British and subsequent Kenyan administrations preferred to invest in the fertile Rift Valley over the arid and semi-arid northeastern area while also discriminating against ethnic Somalis for perceived secessionism in favor of joining neighboring Somalia.10International Crisis Group, ‘Kenya’s Somali North East: Devolution and Security,’ 17 November 2015 ; Oscar Gakuo Mwangi, ‘Kenya violence: 5 key drivers of the decades-long conflict in the north and what to do about them,’ The Conversation, 9 November 2022 Communities in the northeastern area were further targeted in the Kenyan government’s crackdown following al-Shabaab’s high-profile attacks in Kenya in the early 2010s.11Oscar Gakuo Mwangi, ‘Kenya violence: 5 key drivers of the decades-long conflict in the north and what to do about them,’ The Conversation, 9 November 2022 ; International Crisis Group, ‘Al-Shabaab Five Years after Westgate: Still a Menace in East Africa,’ 21 September 2018 The northeastern area also has its own political movements and institutions that are often detached from the political wrangling in western and central Kenya, especially after governance and financial control were devolved to the county administrations in 2013.12Oscar Gakuo Mwangi, ‘Kenya violence: 5 key drivers of the decades-long conflict in the north and what to do about them,’ The Conversation, 9 November 2022 ; Mũturi Njeri, ‘Kenya That was Never Kenyan,’ Medium, 13 April 2015; Abdullahi Abdille Shahow, ‘Devolution Has Not Delivered for the People of North-Eastern Kenya,’ The Elephant, 24 February 2023

The Gen Z movement grapples with riots and police violence

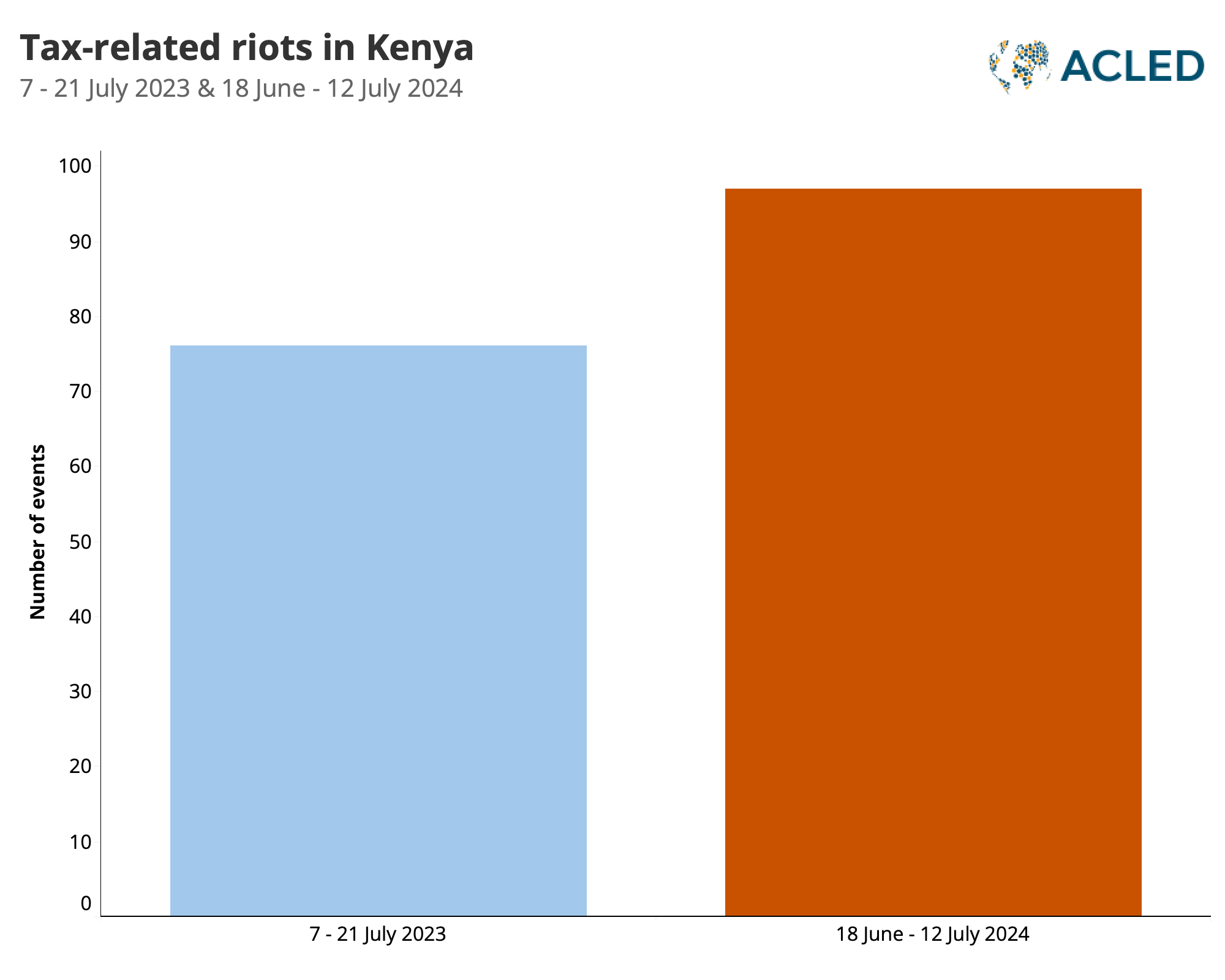

The storming and burning of the parliament on 25 June marked a turning point in the violence, as at least 13 demonstrators and bystanders were killed and another 120 people suffered bullet wounds. On that day alone, anti-tax demonstrators separately attempted to storm the Githurai Mwiki police station in Nairobi and the state house in Mombasa, burned down a hotel housing a parliamentarian’s office in Naivasha in Nakuru county, attempted to storm parliamentarians’ homes in Molo and Nakuru in the same county, and attacked parliamentarian-owned businesses in Eldoret in Uasin Gishu county and Nyeri, Naro Moru, and Karatina in Nyeri county. While digital organizing has been key to enabling the Gen Z protests, the targeting of public officials has also been facilitated by the widespread sharing of officials’ personal information on social media in a trend called tuwasalimie, or “let us greet them.”13Jurist News, ‘Gen Z Leads Digital Uprising Against Economic Injustice in Kenya,’ 10 July 2024 Thus, despite the grassroots organizers’ emphasis on peaceful, well-organized protest, some protests have descended into rioting and looting. Between 18 June to 12 July, there were 97 tax-related riots, including at least 20 events that involved looting, including of supermarkets, restaurants, and shops. Compared to the previous tax-related riots in 2023, there was a 28% increase in events (see graph below). As the movement is decentralized and without recognized leaders, there are few avenues for activists to ensure the demonstrations remain peaceful.14Aaron Ross and Giulia Paravicini, ‘Kenya’s young protesters plot next moves after dramatic tax win,’ Reuters, 28 June 2024

Meanwhile, Kenya’s police continue to respond with tear gas, batons, and live bullets. Among the 215 tax-related demonstrations since 18 June, ACLED records at least 42 demonstrators and bystanders killed and hundreds of demonstrators, bystanders, and police injured. Additionally, Kenya’s security apparatus has initiated more targeted methods of cracking down on protests. The National Intelligence Service and Directorate of Criminal Investigations allegedly formed a covert unit to abduct protest organizers and human rights defenders.15Nation, ‘Inside abduction squads targeting top influencers,’ 26 June 2024 Beginning when unknown perpetrators abducted and interrogated a rights defender on 20 June, ACLED records at least 13 abduction events involving doctors, media influencers, and rights defenders. While the perpetrators’ motives are often unknown, the Police Reforms Working Group Kenya (PRWG-K) coalition reported at least 12 activists were kidnapped before the parliament storming on 25 June and The New York Times reported dozens were kidnapped since the demonstrations began, though most were later released.16dAmnesty International, ‘Kenya: abductions of citizens suspected of involvement in protests violate human rights,’ 25 June 2024; Abdi Latif Dahir, ‘After Deadly Protests, Kenyans Tell of Brutal Abductions,’ New York Times, 6 July 2024

Persisting calls for change leave Ruto’s political future in question

With rising violence and demands for more fundamental change in Kenya, the ultimate trajectory of this demonstration wave remains unclear. Despite Ruto’s rejection of this year’s Finance Bill, the protesters continued mobilizing with far more sweeping and existential objectives related to Kenya’s political economy. The political pressure has yielded some significant results: On 11 July, Ruto met another of the demonstrators’ demands by dismissing most of his cabinet of ministers, including some who were accused of corruption.17Basillioh Rukanga and Wycliffe Muia, ‘Kenyan president sacks cabinet after anti-tax protests,’ BBC, 11 July 2024 This is the first cabinet dissolution since 2005.18Basillioh Rukanga and Wycliffe Muia, ‘Kenyan president sacks cabinet after anti-tax protests,’ BBC, 11 July 2024 The next day, the inspector general of Kenya’s police also resigned.19Al Jazeera, ‘Kenya police chief resigns after criticism over protest crackdown,’ 12 July 2024 However, the battle over balancing the budget and political accountability is rooted in the deeper problems of debt, inequality, and elite politics fueling Kenya’s continuing unrest.20Johnnie Carson, ‘Kenya’s Crisis Shows the Urgency of African Poverty, Corruption, Debt,’ United States Institute of Peace, 27 June 2024 While the movement has oscillated from disciplined and peaceful to more violent and opportunistic actions, the government has accommodated certain demands while overseeing often indiscriminate violence and targeted repression. These are not the first mass cost-of-living protests in Kenya, and, in 2022, Ruto had specifically campaigned on alleviating poverty and inequality by supporting ordinary “hustler” Kenyans.21Peter Lockwood, ‘Kenya unrest: Ruto awakened class politics that now threatens to engulf him,’ The Conversation, 3 July 2024 The demonstrations have divided Ruto’s government, undermined his ability to pass future policies, and ultimately cast doubt on his political future.22David Lewis, ‘Kenya protests expose jet-setting Ruto’s neglect of discontent at home,’ Reuters, 1 July 2024

These protests also have international ramifications, as a militarized response to protesters contrasts with Kenya’s international image and long-standing tradition of mediation and participation in peace operations. Just this year, Ruto has made backchannel proposals for peace in Sudan, hosted high-level talks between opposing parties from South Sudan, and deployed hundreds of police to reestablish order in Haiti.23Aggrey Mutambo and Mawahib Abdallatif, ‘Kenya’s new US-backed bid to save Sudan from ‘genocide’,’ The East African, 25 May 2024; Evelyne Musambi, ‘South Sudan mediation talks launched in Kenya with a hope of ending conflict,’ Associated Press, 9 May 2024; Simon Marks, ‘Kenya’s Mission to Haiti Faces Scrutiny After Deadly Protests,’ Bloomberg, 3 July 2024 The storming of parliament coincided with the first deployment of Kenyan police officers to Haiti — a UN-sanctioned mission that the United States largely advocated for.24Simon Marks, ‘Kenya’s Mission to Haiti Faces Scrutiny After Deadly Protests,’ Bloomberg, 3 July 2024 Both the Haiti deployment and Ruto’s May visit to the US to build economic and military ties received intense criticism at home, with multiple legal challenges to the deployment in Kenya’s courts.25Mariama Diallo, ‘Kenyans wonder why police are deployed to Haiti while unrest churns at home,’ Voice of America, 26 June 2024; Peter Fabricius, ‘William Ruto wins in Washington – but does Kenya?,’ Institute for Security Studies, 31 May 2024; Reuters, ‘Kenyan lawyers move to block police deployment to Haiti,’ 17 May 2024 Additionally, many protesters have criticized Ruto for listening to the tax recommendations of the International Monetary Fund, a part of the US-founded Bretton Woods system.26Shola Lawal, ‘What do the IMF and foreign debt have to do with Kenya’s current crisis?,’ Al Jazeera, 7 July 2024; Fadhel Kaboub, ‘Why are the US and IMF imposing draconian austerity measures on Kenya?,’ The Guardian, 10 July 2024 Ultimately, these protests reflect the modern challenges facing Kenya, including the international debt crisis, systematic corruption, militarization, and the search for international allies and recognition.27Patricia Cohen and Keith Bradsher, ‘Behind the Deadly Unrest in Kenya, a Staggering and Painful National Debt,’ New York Times, 26 June 2024; Johnnie Carson, ‘Kenya’s Crisis Shows the Urgency of African Poverty, Corruption, Debt,’ United States Institute of Peace, 27 June 2024