Situation Update | September 2024

Artillery shelling and airstrikes surge in Sudan

16 September 2024

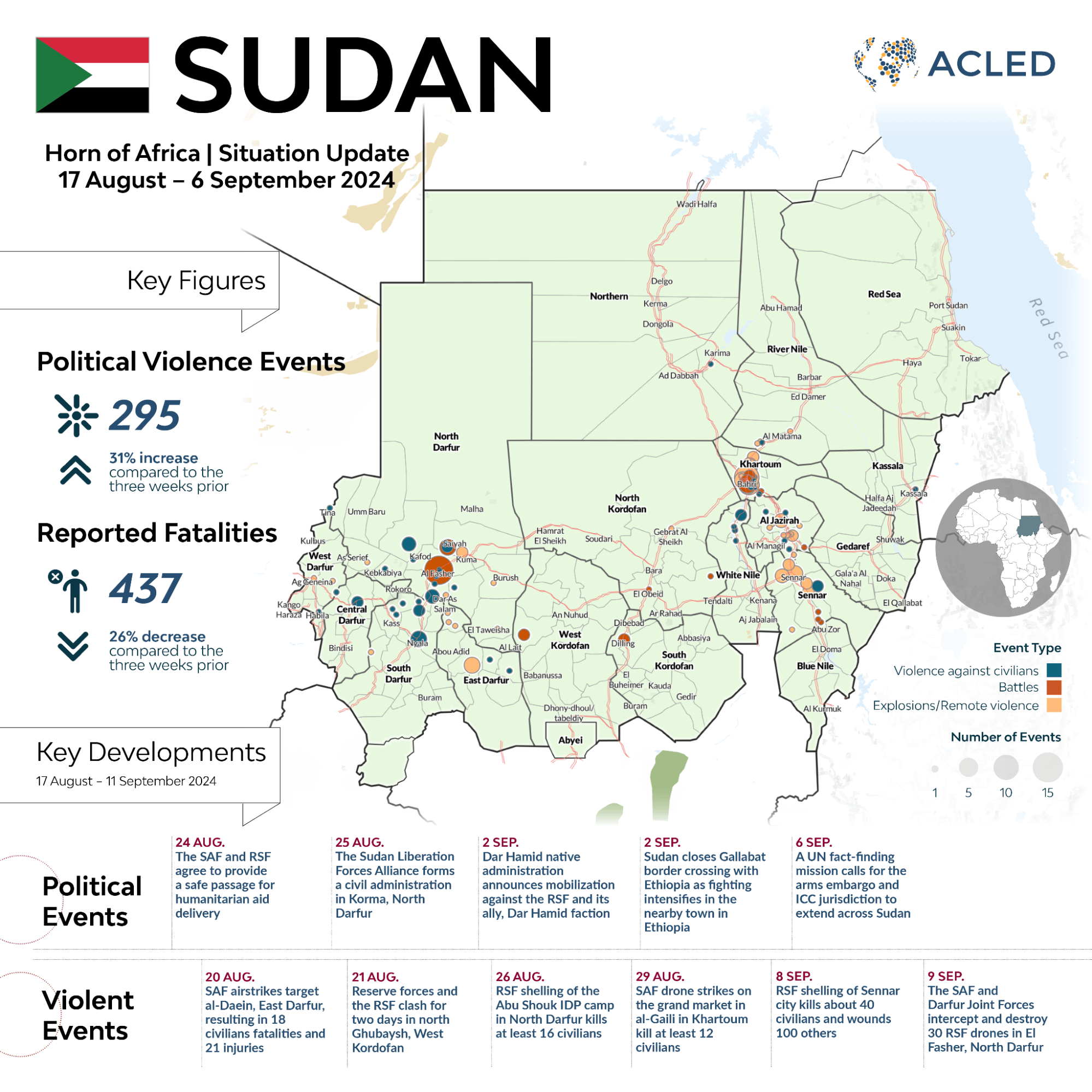

Sudan at a Glance: 17 August – 6 September 2024

VITAL TRENDS

- Since fighting first broke out between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) on 15 April 2023, ACLED records over 7,623 events of political violence and more than 23,015 reported fatalities in Sudan.1On 5 September 2024, ACLED released corrections to the Sudan data that updated events with fatalities in West Darfur state, as reported by Human Rights Watch (HRW) in its published report titled ‘The Massalit Will Not Come Home’: Ethnic Cleansing and Crimes Against Humanity in El Geneina, West Darfur, Sudan. The new information from HRW resulted in ACLED recording 2,635 additional fatalities in West Darfur during the period of April to November 2023. For more on how ACLED incorporated the information from the HRW report, see this update in the ACLED Knowledge Base.

- From 17 August to 6 September 2024, ACLED records over 290 political violence events and over 430 reported fatalities.

- Most political violence was recorded in Khartoum and North Darfur states during the reporting period, with 149 and 57 events and 117 and 163 reported fatalities, respectively.

- The most common event type was explosions/remote violence, with 175 events recorded, followed by battles, with 67 events. Compared to the previous three weeks, ACLED records a 75% increase in explosions/remote violence events. Most of these events were recorded in Khartoum.

Artillery shelling and airstrikes surge in Sudan

Both the SAF and RSF escalated their use of explosives and remote violence in multiple regions of Sudan, most notably in Khartoum and Darfur, as battle events decreased across the country. ACLED records a high number of artillery by both parties in Khartoum, with the SAF also increasing airstrikes on RSF-controlled areas in Darfur. Amid the strikes, a two-day armed clash between two groups of the RSF was recorded in North Darfur state, highlighting the ongoing threat of internal divisions within the RSF’s patchwork of militias.

Elsewhere, the RSF managed to advance and secure positions within Blue Nile state. In addition to fighting with the SAF, the RSF’s expansion to Blue Nile state could create a situation of fighting between three parties, including Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-North (SPLM-N) led by Abdelaziz al-Hilu, as this group controls some areas in south Blue Nile state.

The escalation in remote violence alongside the expanding conflict in Blue Nile state comes amid the failure of the most recent round of ceasefire talks in Switzerland, sponsored by the United States and Saudi Arabia, to bring the warring parties to the negotiation table.2Al Jazeera, ‘Sudan army chief criticises Geneva talks, vows to continue fighting RSF,’ 24 August 2024 The ongoing failure to engage these parties in mediation talks has converged with multiple crises, including severe flooding and widespread health emergencies, driving the ongoing deterioration of the situation in Sudan. Both sides emphasize the importance of facilitating humanitarian aid and ensuring it remains unobstructed,3Al Jazeera, ‘Sudan war mediators welcome new pledges on humanitarian access,’ 17 August 2024 particularly as famine conditions worsen across several regions. Nevertheless, incidents of looting have plagued some aid convoys, although deliveries have continued to flow through the Adre border crossing and Port Sudan airport.4Sudan Tribune, ‘Darfur gov’t accuses RSF of looting aid as humanitarian crisis deepens,’ 2 September 2024; United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), ‘Sudan: Adre border crossing situation update Flash Update No. 01,’ 27 August 2024; Zawya, ‘Ninth Kuwaiti aid planeload arrives in Sudan,’ 2 September 2024 Furthermore, flooding has severed key roads in northern, eastern, and western Sudan,5United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, ‘Sudan: Humanitarian impact of heavy rains and flooding Flash Update No. 03,’ 25 August 2024; Adré Murnei, ‘Darfur and Sudan aid distribution hampered as bridges succumb to floods,’ Radio Dabanga, 26 August 2024; ReliefWeb, ‘Sudan Floods 2024 – DREF Operation (MDRSD034),’ 6 September 2024 further complicating humanitarian efforts.

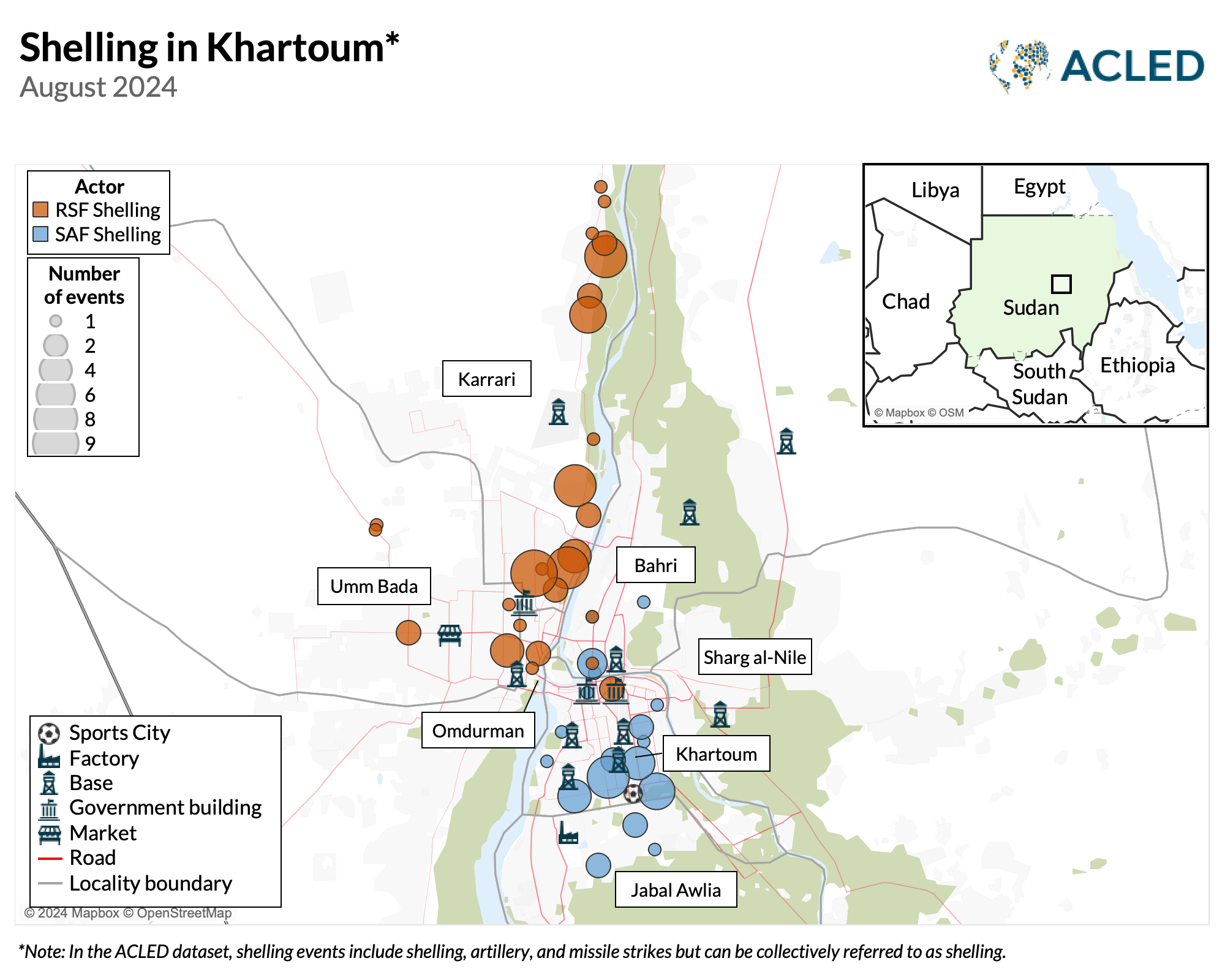

Stalemate drives increasing shelling in Khartoum

Armed clashes between the RSF and SAF continued to decline in Khartoum in August. Since the SAF linked its troops in northern and southern Omdurman, there has been a stalemate between the two parties in Khartoum. As of the time of writing, the SAF controls Karrari locality and parts of Omdurman and Umm Bada, while the RSF maintains control over the remaining parts of Khartoum, including its strongholds in southern Khartoum, Jabal Awlia, Bahri, Sharg al-Nile, and portions of Omdurman and Umm Bada.

However, the latest round of ceasefire talks in August coincided with an escalation in artillery shelling between the SAF and RSF in Khartoum, likely in an effort to strengthen their negotiating positions ahead of any further potential ceasefire talks. ACLED records at least 110 distinct artillery fire events in August in the Khartoum area. The last time such a high number of artillery shelling was recorded was in January, with 158 events.

But both sides have limited capacity to expand their territorial control because their forces are also fighting multiple fronts in North Darfur and Sennar states. Consequently, artillery attacks have become a key tactic, especially for the RSF, to disrupt the day-to-day activities of civilians in areas under opposing control, as reflected in the geographic focus of shelling in August. Carrying out the majority of artillery shelling (67%) in August, the RSF primarily targeted Karrari (see map below). Since the war began, the SAF has been heavily deployed in Karrari and has successfully repelled any advances by the RSF. As a result, the locality has not experienced any significant RSF incursions. Karrari is widely perceived as one of the safer locations in Khartoum, with some people even returning to their homes after they were forced to flee their residences at the peak of the conflict in Khartoum.6Sudan News Agency, ‘Karari locality is witnessing normal stability in public life,’ 21 June 2024; Sudan Tribune, ‘At least 15 killed in artillery shelling of Omdurman market,’ 4 November 2023 This is because Karrari is in the northern part of Omdurman city and still linked to other SAF-controlled areas in the north and east as far as Port Sudan, away from the frontline.

Contrasting with falling levels of armed clashes across the region in August, armed clashes intensified in the north of Bahri city at the beginning of September, particularly around the SAF’s Reconnaissance and Weapons Corps bases in the Hattab and Kadaro areas. For months, the RSF’s attempts to overtake SAF bases in Bahri city had declined as its focus shifted toward operations in other states. The clashes in September are linked to the SAF troops cutting off fuel supplies from the al-Gaili oil refinery to RSF-controlled areas south of Bahri. To eliminate this threat, the RSF launched a multi-front offensive on the two bases from three axes: al-Gaili from the north, Kafouri from the south, and Sharg al-Nile from the southeast. Despite the RSF’s coordinated efforts, the SAF successfully repelled their offensives. The SAF forces inflicted heavy casualties on the RSF, including the death of the brigadier general leading the assault.7Sudan Tribune, ‘Sudan army repels RSF attack on strategic base in Khartoum Bahri,’ 3 September 2024 The al-Gaili oil refinery is a vital fuel source for RSF forces operating in the Khartoum tri-cities. Moreover, the ongoing rainy season has damaged road networks, making fuel transport from other states even more difficult. If the RSF succeeds in capturing the two SAF bases in northern Bahri, its next likely objective will be the SAF Signal Corps base in southern Bahri, the last SAF-controlled position in the city outside of RSF control.

The RSF marches toward Blue Nile

The RSF has aggressively expanded its control in Sennar state since taking control of its capital, Singa, in late June. When the RSF captured the cities of al-Dali and al-Mazmoum in the southwest Sennar state on 2 July, it secured a significant part of the southern borders of Sennar state, adjacent to Blue Nile state. This expansion is an attempt to secure key locations, consolidating its hold over Sennar state and gaining access to Blue Nile. The SAF still maintains control of Sennar city, with an eastern corridor connecting SAF troops in the city to those in Gedaref state, providing a supply route and potential escape path in case the RSF manages to take control of the city.

In early August, the SAF deployed thousands of soldiers in al-Tadamon and al-Roseires localities to defend Damazine, the capital of Blue Nile state, from a potential RSF attack. Despite the SAF deployment, the RSF began to expand to Blue Nile state, particularly targeting several villages within al-Tadamon. Some villages like Galagni — located in Sennar state at the national road linking Sennar and Blue Nile states — resisted the RSF’s attempts. On 11 August, locals in Galagni took up sticks and farming tools against the RSF as troops were entering the village in an attempt to abduct women and girls, killing three RSF fighters. The RSF retaliated against civilians in Galagni by firing artillery and machine gun rounds into the village, resulting in at least 18 reported deaths, though some reports indicate over 100 fatalities.8Ed Damazin, ‘More than 100 killed in RSF revenge attack on Sudan village,’ Radio Dabanga, 19 August 2024 Over 150 civilians were injured, and several women were abducted during the attack.

The SAF responded by advancing from Blue Nile state, triggering heavy battles. On 26 August, the SAF took control of the Galagni village and advanced north to capture Bonzoga village in Sennar. However, SAF troops later withdrew from Bonzoga, retreating south to the Galagni area. Their withdrawal was likely related to SAF concerns about advancing too deep into mostly RSF-controlled Sennar state and distracting themselves from defending Blue Nile state.

The RSF’s push toward Blue Nile state presents a substantial threat to SAF troops stationed in Damazine. Although the RSF withdrew from newly gained positions in al-Tadamon locality and retreated to Sennar on 9 September, its actions may have been driven by a motive to gather information on the geography of the region to assess its strategy. If the RSF continues its push to seize control of Blue Nile and attempts to capture Damazine, the region could face a scenario similar to South Kordofan. In that case, the SPLM-N faction led by al-Hilu, which currently controls the southern territories of Blue Nile, may take advantage of the SAF’s distraction to expand its areas of control to the north. This would put the SAF in the middle of Blue Nile state, leading its forces to fight the RSF in the north and SPLM-N in the south of Blue Nile.

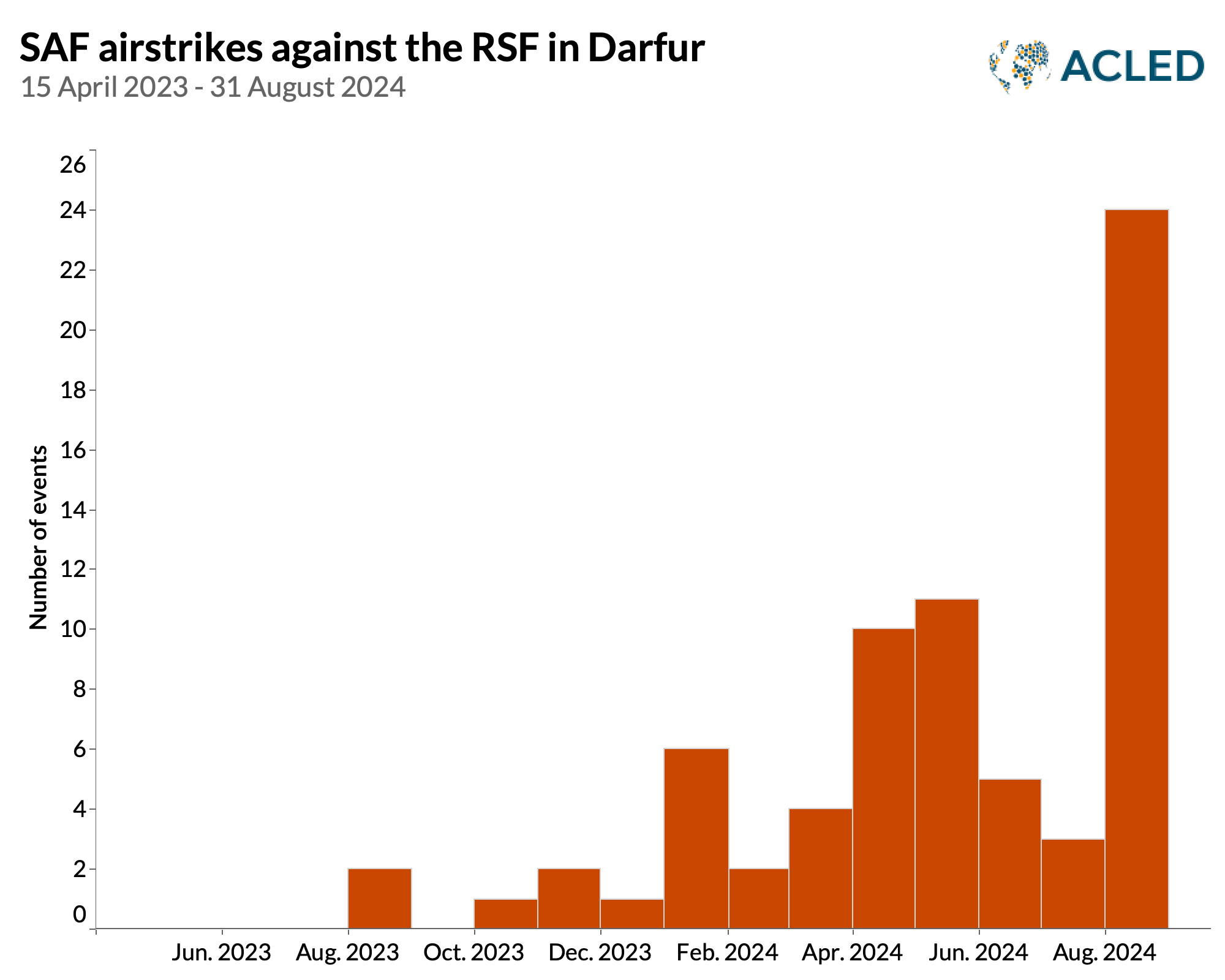

RSF allies in Darfur clash over local interests

In August, the number of SAF airstrikes against the RSF increased in Darfur region (see graph below). This surge might be linked to the SAF’s receipt of 15 new fighter jets supplied by Russia and Egypt.9Ayin Network, ‘More weapons embolden Sudan’s army to reject critical peace talks,’ 26 August 2024; The East African, ‘Sudan strengthens ties with Russia as eyes on arms, human crisis,’ 25 August 2024 The SAF’s air campaign appears aimed at disrupting the RSF’s mobilization of thousands of fighters reportedly preparing for a renewed assault on El Fasher city,10Sudan Tribune, ‘Sudan’s War Escalates: RSF shells Omdurman, battles rage in Sennar, Gedaref,’ 30 August 2024 which remains under the control of the SAF and its ally the Darfur Joint Forces.11The Darfur Joint Forces umbrella was established as a neutral force consisting of signatories of the 2021 Juba Peace Agreement which was deployed on 27 April 2023 to protect civilians in El Fasher. However, since December 2023, various members of the Joint Forces have changed their alliances. Some backed the SAF, while others maintained their neutrality. From 1 August to 6 September, ACLED records 50 SAF airstrikes across all Darfur states, while in the previous five weeks, there were only three SAF airstrikes in Darfur, all related to the ongoing battle for El Fasher. The airstrikes have had devastating effects in these states, including the destruction of a teaching hospital in al-Daein in East Darfur, which resulted in 18 civilian fatalities.

In the meantime, internal tensions within the RSF in Darfur intensified. On 26 August, two RSF groups — one from the Rizeigat ethnic group and the other from the Ziyadiya ethnic group — engaged in two days of violent confrontations in Mellit city, North Darfur. This city is predominantly inhabited by the Ziyadiya ethnic group, while the RSF has been dominated by Rizeigat, two ethnic groups that are not known to have previously been in conflict. The armed clash began when Ziyadiya fighters, who were protecting the market, wanted to stop Rizeigat fighters from outside the city who attempted to loot a market.

The RSF’s composition of various militias with differing agendas often leads to internal clashes as these groups exploit the national war to pursue their local interests. While the clashes in Mellit were not linked to any known preexisting conflicts, disputes over land and natural resources have fueled persistent conflicts, such as the ongoing clashes between the Salamat and Beni Halba, as well as the Salamat and Habbaniya, throughout 2023. Additionally, conflict over leadership succession within the RSF has sparked further internal confrontations in Khartoum, Sennar, and North Kordofan, highlighting the complex and fragmented nature of the RSF’s militia-based organization. These latest clashes underscore the threat of deepening internal divisions within the RSF. On 30 August, the Ziyadiya and Rizeigat ethnic groups reached an agreement, committing to blood compensation and reforming the forces responsible for market security to prevent further violence and avoid renewed clashes.12Darfur 24, ‘An agreement to reopen Mellit market and oblige the Rapid Support to pay blood money for the dead,’ 31 August 2024